This is the second of a series of monthly columns by Andrew Kliman that will be published here in English and at Radikal Portal, a new project, in Norwegian.

“The 99%” and “the 1%” … of What?

February 14, 2013

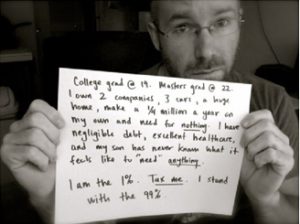

By now, everyone has heard about “the 1%” that has supposedly been reaping almost all of the gains in income in the U.S., while “the 99%” have been left in the dust, lagging further and further behind. This notion has been promoted by many liberal and leftist economists and by prestigious publications like the New York Times. And influential segments of the 2011 Occupy movement were largely successful in turning the movement into a vehicle for “the 99%” to protest against “the 1%.”

But almost nobody has bothered to ask, “the 99% and the 1% of what?”

The answer—which I’ll get to below–– is surprising. The massive income gains of “the 1%” don’t mean what almost everyone has thought they mean. And partly because the data on the income share of “the top 1%” are little understood and often misunderstood, the extent of the increase in income inequality and, I think, the importance of the issue, have been exaggerated.

Why does this matter? I think there are several reasons. One is that the disproportionate concern over inequality can divert attention from major economic problems like the economy’s failure to rebound from the Great Recession, and what to do about that. And it can tend to divert attention from concrete problems like mass unemployment, people losing their homes, and poverty. And what about the fact, which dominates most people’s lives, that they are forced to do what bosses tell them to do, day after day, year after year––or else starve? Why is there so little outrage about this, or even concern about it? Certainly, the Occupy movement generally focused less on these concrete problems and more on the abstraction “rising inequality.” But the concrete problems are directly about people’s well-being, while concern over inequality isn’t. It may in some cases be driven instead by envy, resentment, or the desire to find scapegoats for other economic and social problems.

Second, the national- and first-world-centered framing of the inequality issue is troubling. One-twelfth of “the 99%” in the U.S., more than 25 million people, are part of “the 1%” on the global level. And even U.S. residents whose incomes are at this country’s poverty line are nonetheless in the top 14% of the global income distribution. (The first statistic is based on data reported here; the second is reported here.) Shouldn’t the focus on inequality be broadened, and wouldn’t it be broadened if concern for people’s well-being were the overriding motivation?

Third, there are massive social divisions, between rich and poor, owners and workers, bosses and workers, and so on, that talk of “the 99%” covers over. We are hardly “all in this together.” An unmarried person with income of $366,622 in 2011 was part of “the 99%,” but had very little in common with most Americans. Why should a (problematic) statistical finding that the income of “the 1%” rose much faster than everyone else’s income come to dominate how we understand and grapple with these social divisions? It may be politically expedient in the very short run for a social movement to declare that it represents the interests of 99% of the population, but it seems to me that such declarations have proven to be hollow. In order to forge real unity and create a social movement that’s big enough to change society, a lot of hard work and hard thinking are needed in order to identify genuine commonalities of aspirations and interests, and in order to break down the many economic, racial, gender, philosophical, and other divisions that plague these movements.

Fourth, I think that the disproportionate concern over inequality largely reflects––and encourages––a distorted understanding of the causes of the Great Recession and the economic malaise that persists long after the recession ended. As I discussed in chapter 8 of my book, The Failure of Capitalist Production, there are very strong reasons, both factual and theoretical, to reject the popular underconsumptionist notion that the Great Recession was caused largely by a substantial decline in the share of output that the U.S. working class was able to buy with its income (i.e., without going deeper into debt). One is that no such decline occurred.

Elsewhere in the book, I argued that a long-term fall in U.S. corporations’ rate of profit was a key indirect cause of the recession. Unfortunately, this argument has frequently been dismissed––without dealing with the data I put forward––on the grounds that “we all know” that wages have stagnated and workers’ share of the product has fallen markedly, and that these trends must have caused the rate of profit to rise. (They would indeed have done so, had they taken place, but they didn’t.) Similarly, the book’s findings that pertain to compensation of workers have been dismissed on the grounds that they contradict the well-known fact that inequality has risen markedly. (But there is only an apparent contradiction, not an actual one.)

Since the evidence suggests that upward redistribution of income isn’t a significant cause of the recession and the persistent economic malaise, downward redistribution of income isn’t going to extricate the economy from the malaise. After all, profit is the fuel on which capitalism runs, so a downward redistribution of income that cuts into profit will tend to destabilize the system even further. Working people’s struggles to protect their jobs, incomes, and homes certainly deserve our support, but there’s no good reason to base that support on the dubious notion that successful struggles will improve the functioning of the capitalist system. Surely a Left that prides itself on putting “people before profit” can come up with sounder bases for supporting these struggles.

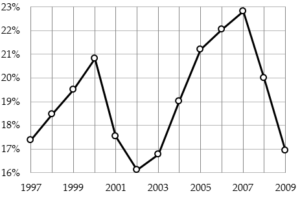

Indeed, if downward redistribution were a solution, the U.S. economy should have rebounded smartly from the recession years ago. Between 2007 and 2009, the income of “the 1%” fell by more than one-third, while everyone else experience a fall of just 4%. More than 70% of the total loss of income was borne by “the 1%,” and as the graph below shows, its share of income fell from an all-time high to a lower level than in 1997.

Share of Income of “the 1%” in the U.S.

Source: Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income.

Note: “Income” refers to adjusted gross income as defined by the IRS.

But what are these data telling us, anyway, and what does “the 1%” really mean?

The story begins, a decade ago, with the surprising findings of Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, two French economists who have been close to that country’s Socialist Party. Prior to their work, economists generally agreed that income inequality in the U.S. rose rapidly in the 1980s, but that the growth of inequality slowed down greatly after about 1993. But Piketty and Saez reported a shockingly large––and continuing––increase in the incomes of “the 1%” relative to the rest of the population.

Are animated figures in “the 1%”?

For a long time, it was generally believed that Piketty and Saez’s conclusions differed so drastically from the previous consensus because their data came from the tax authority (Internal Revenue Service), while other researchers employed Census Bureau data. And it was widely believed that the studies based on Census data had failed to capture the rise in income at the top of the income distribution because the Census data were inferior. (The Census Bureau censors information on those with very high incomes, to protect their anonymity, so researchers have to employ a good deal of guesswork in order to estimate top incomes.)

Enter Richard V. Burkhauser. The tide had swung so much in favor of the Piketty and Saez view that a major economics journal rejected a paper by Burkhauser and co-authors simply because its findings, based on Census data, were at variance with those of Piketty and Saez. So Burkhauser and his colleagues looked into why the conclusions of the Census-based and tax-based studies were so different. After four years of work, they published a remarkable paper last year that was basically able to reconcile the two sets of data.[1] They showed that they could obtain results from Census data that are very much like those of Piketty and Saez, if they employed Piketty and Saez’s definition of income and their income-sharing “units.” Thus, the reason why Piketty and Saez had come up with such shocking conclusions about rising inequality had little to do with the fact that they had a different data source. It had to do with fact that they were using a very different definition of income and studying very different income-sharing “units.”

A related and equally remarkable paper by Burkhauser and colleagues,[2] also published last year, showed just how much depends on the definition of income and the choice of “units.” The Piketty-Saez methods imply that the real (inflation-adjusted) income of those in the middle (the median income) increased by just 3.2% between 1979 and 2007 in the U.S., but the methods most commonly employed imply that it increased by 23.6%, more than seven times as much!

This is partly because Piketty and Saez’s definition of income excludes “transfer payments,” things like government-provided pension income (Social Security, etc.), unemployment insurance benefits, and public assistance. And it’s partly because Piketty and Saez’s “units” are peculiar, something called “tax units”––unmarried individuals, or married couples filing a joint tax return, and, in both cases, any dependent children––while other researchers’ “units” are typically households adjusted for household size. (Because the number of “tax units” per household has risen considerably as the marriage rate has declined, Piketty and Saez’s method increasingly spreads out rising income among more and more “tax units,” and thereby dilutes the rise.)

Burkhauser and colleagues also found that, if we consider after-tax income, and include the value of employer- and government-provided health insurance in the definition of income, median income of size-adjusted households rose by 36.7%. This is more than eleven times as much as the increase we get using Piketty and Saez’s methods.

In the same paper, Burkhauser and colleagues also showed how much the definition of income and the choice of “units” affect trends in income inequality. Using Piketty-Saez methods, they found that the bottom 20% of the population suffered a 33% fall in real income between 1979 and 2007, while the top 20% enjoyed a 32.7% gain. But when they used the most common definition of income and choice of “units,” they found that the income of the bottom 20% rose by 9.9% while the income of the top 20% rose by 42%. And when they considered after-tax income and counted health benefits as income, they found that the income of the bottom 20% of size-adjusted households rose by 26.4% while the top 20% enjoyed a 52.6% gain. So inequality increased, according to all three methods, but Piketty-Saez’s methods resulted in the biggest increase, by far, and only their methods, not the others, imply that the income of those at the bottom fell.

The findings of Burkhauser and colleagues seem to have put Piketty and Saez on the defensive. Saez told the New York Times that he hopes to be able to produce data on “post-tax, post-transfer, per adult, adding non-taxable income sources, etc.,” which seems to be tantamount to an admission that their prior studies have employed a questionable definition of income and choice of “units.” Piketty told the Times, “We have always been very clear about the fact that we study changes in the distribution of market income. Our point is that top incomes have taken a disproportionate share of market income growth over the past 30 years, and as a consequence that the market incomes of the lower and middle class have stagnated.”

And he’s right (though other definitions of market income would, for instance, include Social Security income). But there are a couple of problems with Piketty’s defense. One is that he and Saez, not to mention news sources and other economists who repeat their findings, have almost always referred to “income” without any qualifying adjective. The other is that, until the studies by Burkhauser and colleagues came out, no one paid much attention to the exact way in which income was defined, because no one knew that the different definitions matter as much as they do.

So now we have the answer to the question with which we began: “the 99% and the 1% of what?” Not people, not families, not households, but “tax units.” Because the number of “tax units” per household varies and has risen over time, especially among lower-income people (as the income inequality findings suggest), measuring income trends in terms of them is rather like measuring lengths using a rubber ruler. And now we know the meaning of statements like “the top 1% has reaped most of the gains in income”––“the top 1% of ‘tax units,’ not adjusted for size, has reaped most of the gains in before-tax, before-transfer, income received from taxable sources of income.” But in another sense of the word “meaning,” I’m not at all sure that we know what this means. If the significance of this is clear to you, good. It isn’t to me.

rubber ruler

I basically agree with Saez’s view of the import of the studies by Burkhauser and colleagues: “cash market income of the bottom 99 percent of adults has stagnated but the bottom 99 percent get much more expensive private and government provided health care benefits, some more government transfers, and they have fewer kids.” So their total income, and especially their total income per person, has not stagnated. And I agree with Saez that “[t]his does not seem like a great situation … from a conservative point of view.” The rise in the income of “the 99%” is partly the result of things that are anathema to much of the right: family planning and government-provided benefits won through social struggles. So I don’t think that the remarkable findings of Burkhauser and his colleagues can easily be situated on a left-to-right spectrum.

Andrew Kliman

Andrew Kliman is the author of The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession (Pluto Books, 2012) and Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency (Lexington Books, 2007).

[1] Richard V. Burkhauser, Shuaizhang Feng, Stephen P. Jenkins, and Jeff Larrimore, “Recent Trends in Top Income Shares in the United States: Reconciling Estimates from March CPS and IRS Tax Return Data,” Review of Economics and Statistics 94:2, May 2012, 371–88.

[2] Richard V. Burkhauser, Jeff Larrimore, and Kosali I. Simon, “A ‘Second Opinion’ on the Economic Health of the American Middle Class,” National Tax Journal, March 2012, 65 (1), 7–32.

I always understood the 99% as representing the portion of the working population (employees) and 1% as the capitalist class (employers) in the U.S.. And indeed, the ILO data shows that this is the class structure in the USA today. For example, in Brazil it is more or less 75% employees, employers 3% and 22% independent (own account). As more developed capitalist country more proportion to the working class tends to 99%. This means that we are the majority relatively who oppress us, why we can not reverse the game?

Dayani Aquino,

I also understood 99% to mean the workers, and 1% the owners of the means of production. Unfortunately, having participated in Occupy Orlando for some time, I found that everyone else considered the 1% to be the filthy rich, who had ruined the middle class by their greed and nefarious finance practices. To some degree this is true (i.e., lots of these people are greedy, nefarious, and do impact middle class lives). Kliman is right to point out that there are structural issues in relation to capitalism that cannot be reconciled by ending greed, or nefarious behavior. Moreover, to only be concerned about the restoration of the middle-class (not saying you are, but many Occupiers were) is to have a blind spot for those outside of the middle-class entirely (e.g., homeless, students in dorms, illegal and many legal immigrants, etc).

Unfortunately my experience with Occupy led me to conclude that – while these people are genuine, sincere, and their heart is in the right place – theoretically their grasp of core structural issues was in need of serious work. Capitalism as a system was rarely mentioned, but people that occupy certain positions within capitalism were always demonized as THE problem. That or the solution was just to get X number/members of congressmen replaced. Of course it doesn’t matter who is in congress since capitalism is inherently cyclical, and its busts frequently impoverish those least responsible.

Either way, you’re right that the numbers are on the side of the exploited, and something really should be done about exploitation, by those who have the numbers to do so.

why don’t you try to organize and hold public space and attention for much of a year with your slogans?

Oh, I forgot, you don’t have a slogan and you didn’t do that..

To me, the framing of this piece amounts to an unfortunate academicism in closely critiquing the slogan of the “we are the 99%” Occupy Wall Street movement.

You can write a million word manifesto with all appropriate nuances included, but that won’t bring thousands into the street, grabbing space and a spotlight for months. To quote our head of state, “you didn’t build that.”

A slogan is ALWAYS necessarily an over-simplification that hopefully does not do too much violence to actual truth. I know your real target was Piketty, not OWS, but gee…you managed to be BOTH trivial and off the mark.

Was Occupy unfair in its choice of targets? I think there was unschooled brilliance in choosing Wall Street, rather than Washington DC, to take an economic political complaint to. That speaks volumes with no words.

The connection to the 2008 crash was made, both implicitly & explicitly – by participants, media, and pretty much everyone.

“We’re hurting and these are the people responsible” was the inescapable subtext of simply being there, even if the Occupy folk said nothing else. Indeed, not much else that was coherent came out of those gatherings afterward.

Far from “diverting” attention from unemployment/recession/poverty OWS focused attention on the genuine power centers that flip the switches and control the levers for our nation and world.

The inequality complained of by OWS was NOT so much about relative shares of either income or wealth — but rather, the inequality of political control which Wall Street symbolizes.

As for the substance of your dispute with Piketty, his research focused on the distribution of gains from growth.

THAT has been a minor but persistent theme in much recent popular discussion: while the productivity of workers has doubled in a little over a generation, most private gains accrued to the top of the income distribution.

[The wealth distribution is even more skewed than income, though this is little commented upon in general. Piketty, to his credit, made it central to his work]

Piketty zeroes in on this issue of unequal gains from productivity and growth, along with the outsize growth in unearned gains from capital, rather than work.

These two foci assault a central moral justification for inequality under capitalism : that unequal rewards are allegedly commensurate with greater effort and output attributable to the hard-working bourgeoisie. Instead, Piketty tried to make the point that you can’t justify the gains by these folks’ marginal productivity.

Will changing that circumstance help solve all economic problems? Maybe not, but it will address the inequities complained of and put more money into consumption instead of growth and trickle-down .

The comments from Steve B and anonymous reflect a lot of what’s wrong with the left. Supposedly, truth is unimportant and worked-out ideas with some real content are unimportant. He even approves of doing violence to the truth as long as one doesn’t do “too much” violence to it! What is supposedly important is “framing” in order to market your message right, bring thousands(!) into the street and get media attention.

And just where are those thousands in the streets and the media attention NOW? You have only to listen to the silence.

Could it be that what went wrong is practice based on the kind of attitudes that Steve B and anonymous reflect? Yep.

I’m looking forward to MHI’s upcoming classes on “Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program as New Foundation for Organization.”

Piketty is now a household word. Just what is “trivial” about the fact that the measure of “income” he employs, which people assume to be a normal concept of income, is actually extremely peculiar and the fact that his numbers are therefore very misleading?

Don’t hide behind squishy and subjective words like “trivial.” Is what I say about his and Saez’s measure of income ACCURATE or not? (Oh, I forgot. Truth is unimportant. War is Peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength. The Party can make 2 + 2 = 5. It’s just a matter of framing.)

As I’ve explained elsewhere, the so-called “productivity/compensation gap” is a misleading factoid. In the US, between 1970 and the Great Recession, average employee compensation did keep pace with productivity, and rising pay of CEOs and other top execs had EXTREMELY little to do with the slower growth of median employee compensation. Please see:

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/are_corporations_really_stealing_workers_wages_20140409

and

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/were_top_corporate_executives_really_hogging_workers_wages_20140917

But there I go again, being part of what Dick Cheney called the reality-based community.

To be clear, I was not advocating deliberate falsehoods. I was stating that any slogan necessarily oversimplifies — that, of course, being in the nature of slogans. That’s what I think amounts to a trivial criticism of OWS.

Indeed, any generalization runs the risk of oversimplifying. Including your own.

If your data shows there hasn’t been a productivity wage compensation gap, OK. I will say that Piketty was hardly the first to say otherwise, only the most prominent among those most recently saying so. You are really swimming against the current there, no wonder you seem exasperated. If I repeated a commonplace conception in error, I apologize.

I said that I take his central point to be about the disposition of production earnings from economic growth (as measured in shares of income and wealth or capital) shifting adversely against workers — rather than being about the total share of income coming from all sources declining for workers.

So, I wasn’t sure that he was indeed “misleading” about income as a whole, since I thought he was looking at pre-tax income precisely to make a different point than you were.

But now you that say even that point is incorrect given the data. That’s significant, and I assume you have your good reasons for saying so.

I’m left wondering why you didn’t address that point in this article rather than the one you did about the exclusion of transfer payments from Piketty’s definition of national income.

I’m also left wondering if workers are indeed getting increased hourly compensation commensurate with any increased output, and if they also on average get fully compensated for any losses of income with unemployment compensation & transfer payments, then what exactly IS your beef with capitalism?

If it’s the cyclic downturns, then what’s the difference if those transfer payments fully compensate for loss in income?

If it’s compulsory alienated labor, why do you harp on unemployment as a social problem? Is that a radical critique, or a liberal one? It’s a good thing if workers are getting a greater share of the social product without yielding surplus value, right?

If, for you, ending the production system based on value (as defined by Marx) is a goal in itself, then how would any alternative economic production system be constructed?

Interesting that AK complains that piketty omits transfer payments from income, yet he omits capital gains, royalties, rents, interest, and (it appears) dividends as well in the income to capital, in his quest to show that workers’ wages haven’t fallen behind productivity.

First of all, two wrongs don’t make a right. So, anonymous, am I JUSTIFIED when I point out that Piketty and Saez’s “income” figures are misleading because they exclude Social Security benefits and other transfer-payment income. They don’t count the portion of emploees’ SS benefits that *employers* pay for either when the the employers pays the tax or when the retired worker receives the benefits.

Second of all, you’re wrong; I don’t omit royalties, rents, interest, or dividends. I don’t even know what you’re talking about.

Everybody’s productivity data, not only my own, exclude capital gains because productivity is output per hour and capital gains aren’t part of output. They’re not part of output in the national accounts and they’re not part of it conceptually, either.