by Andrew Kliman

Traducción al español de A. Sebastián Hdez. Solorza:

“No Tengo Tiempo para Creer _ Edwards y Leiter sobre el Pensamiento Económico de Marx”

1. No Joke

Have you heard the one about a philosopher, a humorist, a mathematician, and an economist who walk into a bookstore? They pick up the latest book on Marx and thumb through it.

The philosopher, an ancient Greek, says that he’s better off than people who don’t know but think they know, because he also doesn’t know, but knows that he doesn’t know.

The humorist, a 19th-century American, chimes in: “it is better to know nothing than to know what ain’t so.”

But another patron complains that he can’t tell whether what he believes “is so” or “ain’t so.” “I am a busy man; I have no time for the long course of study which would be necessary to make me in any degree a competent judge of certain questions, or even able to understand the nature of the arguments.”

The mathematician, a 19th-century Englishman, sympathizes with the patron and offers him some time-management advice: “Then [you] should have no time to believe.”

The economist, a 21st-century American and Marxist-Humanist, writes the following commentary on the book.

Jaime Edwards and Brian Leiter, Marx. Abingdon, UK and New York: Routledge, 2025.

LCCN 2024018235 (print) | LCCN 2024018236 (ebook) | ISBN 9781138938502 (hardback) |

ISBN 9781138938519 (paperback) | ISBN 9781315658902 (ebook)

Edwards and Leiter’s book is wide-ranging, covering at least the main aspects of Marx’s thought and life that the authors consider significant. But I will focus here almost exclusively on what it says about Marx’s critique of political economy, especially his value theory, because I think that the book’s treatment of that topic is extremely flawed, and it will take a good deal of care and space to set matters straight and to support my claims adequately and intelligibly.

An introductory text, the book is clearly intended for philosophy students and for philosophy instructors who need to give a lecture or two on Marx. Mid-late 20th-century debates among (mostly) academic philosophers frame much of the discussion of Marx; in particular, the “analytical Marxism” of G.A. Cohen and others weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. Given the book’s genre and its intended audience, which is not especially interested in economic matters, my focus on criticizing what it says about value theory may seem like the humorous review of the movie Reds, by a dentist (starting at 0:16), that focused on criticizing the anachronistically “near-perfect dentition” of the main characters.

But I’m not assuming that what is important to me is important to everyone, or suggesting that it should be. On the contrary, I don’t think that the vast majority of philosophy students and philosophers need to know anything about Marx’s value theory. They don’t have time for the course of study they would need to understand it and judge it competently. Accordingly, they shouldn’t have time to believe anything about it, good, bad, or indifferent.

So I don’t think that a book like Edwards and Leiter’s needed to devote more than a few anodyne sentences to Marx’s value theory. In fact, it would have been prudent to refrain from saying more. The book would have avoided perpetuating error, and it would not have encouraged readers to know what ain’t so or to think they know what they don’t.

“To leave error unrefuted is to encourage intellectual immorality,” as Marx reportedly said. But even though refuting error is morally obligatory, I have learned the hard way that it is almost always a thankless task. Authors don’t take kindly—to put it mildly—to refutation of their errors, nor do their fans, nor do people who want to remain neutral, neither pro- nor anti-truth.

However, I have some reason to hope that the outcome of the present case will be different. Edwards and Leiter indicate that they think that criticism of Marx’s value theory and analysis of capitalism should be fair, when they point out that “not all of it” has been (p. 97). And Brian Leiter, the principal author of the chapter on Marx’s critique of political economy, agrees with what I have said here about knowing what one is talking about before one talks about it. In 2019, Leiter responded to a Substack post about the “irrationality” of Marxism that Michael Huemer, a right-wing (anarcho-capitalist) philosopher, had written. Leiter said that Huemer “does not cover himself in glory with this sophomoric attack,” and that

I think one way to avoid public displays of “irrational” beliefs is to actually know something about the subject you’re discussing, in this case, Marx’s views. Professor Huemer plainly doesn’t, which is why these comments fall so far below his normal argumentative standards. But they do illustrate irrationality in politics well!

Thus, while mistakes regarding theoretical matters are all too often either intentional or induced by lack of concern for truth, I have reason to hope that what we have, in this particular case, are honest mistakes that Edwards and Leiter themselves will want to see corrected.

Although I have written this commentary primarily to fulfill what I regard as a moral obligation, it is not inconceivable that it will be beneficial to some readers. Perhaps some may benefit from its discussion of Marx’s economic thought, especially its correction of some very common misconceptions of what his so-called “labor theory of value” says. And perhaps some may benefit from an object lesson that this commentary provides: to know what one is talking about can be much more difficult than it seems.

With one exception, I will deal exclusively with Edwards and Leiter’s fourth chapter, “Marx’s Economics and the Collapse of Capitalism.” The exception is the next section, which takes up what they say, in their chapter on historical materialism, about China (and other countries) needing to pass through a capitalist stage of development, and about what Marx would have said about this. I feel that the issue is too important, and their treatment of it is too flawed, for me to refrain from responding, even at the cost of digression.

The rest of my commentary discusses much, but by no means all, of chapter 4. I do not address its discussion of Smith’s and Ricardo’s value theories because I lack the expertise to do so competently. I refrain from commenting on some other topics—especially the (in)justice of capitalist exploitation, the fetishism of commodities, the collapse of capitalism, trends in income distribution, and the effects of technological change on employment—because I lack the time to do so properly and my commentary is much too long as it is.

For the same reasons, I avoid commenting on many things Edwards and Leiter say about the topics I do take up. For example, they write (p. 126) that “Marx says it is only a ‘tendency’ that the rate of profit will fall. He cannot establish that it actually will,” which raises the question of whether his falling-rate-of-profit theory even intends to establish that the rate of profit will fall or tends to fall. I (and co-authors) addressed this issue at length elsewhere, but I think it’s better for me to bypass it here. My silence about a particular matter implies neither agreement nor disagreement with what the authors say about it.

As I noted, Section 2 discusses what historical materialism says about whether a capitalist stage of development is necessary. Section 3 is about whether and why Marx’s value theory matters.

Sections 4 through 9 all deal with aspects of price theory. Section 4 discusses the notion that modern price theory is “better” than Marx’s value theory. Section 5 argues that the direct opposition that Edwards and Leiter set up, between the “labor theory of value” and “marginal utility theory,” is a false one. Section 6 addresses their claim that Marx denied that demand is an independent variable in the explanation of values and prices. Section 7 argues that, in both Marx’s theory and neoclassical economic theory, the role that utility plays in the explanation of price and profit is very circumscribed. Section 8 is about the same issue; it discusses what both theories say about the role of demand in the determination of long-run competitive prices. Section 9 responds to Edwards and Leiter’s suggestion that “marginal utility theory” explains prices of production while the “labor theory of value” does not. I show that their view is based on a misunderstanding of what Paul Sweezy said about the issue.

Section 10 discusses Marx’s concept of capitalist exploitation, which is rooted in his value theory, and the alternative physicalist concept that Edwards and Leiter regard (wrongly, in my view) as more viable. Finally, Section 11 takes up the underconsumptionist explanation of capitalist economic crises. Edwards and Leiter regard it as “promising” and as Marx’s own explanation. I argue that it is neither.

2. Historical Materialism: Can the Stage of Capitalist Development be Bypassed?

One chapter in Edwards and Leiter’s book takes up “historical materialism,” that is, Marx’s materialist conception of history. They discuss, among other things, what Marx’s conception implies regarding the relation between capitalist development and possibilities for socialism. Unfortunately, what they say about this is a caricature that serves to whitewash state-capitalism, especially the current market-centered version of Chinese state-capitalism. Even worse, the caricature turns Marx himself into an apologist for it. Edwards and Leiter tell us that

according to historical materialism, capitalist relations of production are essential for the maximal development of productive power in human societies: this is why an orthodox Marxist in Russia in 1917, or China in 1949, or Cuba in 1959 would have demanded the institution of some kind of capitalist relations of production …. [T]he massive growth in productive power in communist China only occurred after Mao’s death and the ‘market’ reforms of Deng Xiaoping. … Marx’s theory of historical materialism would have sided with Deng, since China, given the state of its productive forces, desperately need [sic] capitalist relations of production. [p. 49]

Part of this is correct. The emergence of capitalism was, historically, essential for the development of productivity. And Marx’s materialist conception of history incorporates that fact as a central element. It argues that socialism becomes possible only after humankind has passed through a capitalist stage, because socialist relations of production and forces of production can be established only on the basis of the high level of productivity that capitalism has brought about.

However, Edwards and Leiter’s pro-capitalist conclusions are not straightforward deductions from historical materialism as such. They depend crucially on a further premise that Edwards and Leiter have implicitly added: that every country must develop on its own, in isolation, independently of the others. Given this addition, not only does humankind need to pass through a capitalist stage of development before socialism can be achieved, as Marx argued. In addition, every country must pass through a capitalist stage before socialism can be achieved in that particular country.

But is the additional premise true? Must every country develop independently of the others?

Why can’t there be a world revolution that allows technologically less-developed countries to bypass a capitalist stage of development? That is, why can’t they advance to socialism directly, in partnership with technologically developed countries, on the basis of the high level of productivity that has already been achieved through capitalist development in the latter countries?

This world-revolutionary perspective is incompatible with the additional premise. But it is compatible with historical materialism as such. And “Marx’s theory of historical materialism” (emphasis added) affirmed the world-revolutionary perspective, precisely because Marx explicitly rejected the idea that every country must develop in isolation and must therefore pass through a capitalist stage.

He worked out his view in 1881, in response to a query by Vera Zasulich, a Russian revolutionary. She asked him to comment on whether “the [Russian] rural commune … is capable of developing in a socialist direction, that is, gradually organizing its production and distribution on a collectivist basis.” Or must Russian socialists wait out the “many centuries it will take for capitalism in Russia to reach something like the level of development already attained in Western Europe,” and merely “conduct propaganda solely among the urban workers” in the meantime? She noted that “Marx said so” is often the “strongest argument” put forward by proponents of the latter view.

In the so-called “first draft” of his response, Marx (correctly) denied that he had said so: “I expressly restricted the ‘historical inevitability’ of this process”—proletarianization of the peasantry and the establishment of capitalist production relations—“to the countries of Western Europe” (emphasis in original). And he explained why he had come to the opposite conclusion:

Precisely because it is contemporaneous with capitalist production, the rural commune may appropriate all its positive achievements without undergoing its [terrible] frightful vicissitudes. Russia does not live in isolation from the modern world.

Edwards and Leiter are well aware of Marx’s position on this matter. Elsewhere in their book, they discuss and quote from Marx and Engels’ preface to the second Russian edition of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (pp. 425-426 in vol. 24 of their Collected Works) that they wrote the following year:

Later in life, Marx increasingly took note of growing socialist movements on the margins of the industrialized nations, particularly in Russia ….

Perhaps the struggles in the industrialized centers and the radicalized margins could complement each other? [Marx and Engels] saw the possibility, for instance, that a revolt in Russia could become “the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West.” The … industrialized countries could return the favor by sponsoring industrial advances in the not yet industrialized … nations that would enable them to bypass the stage of bourgeois industrialization that had been requisite in the industrialized center, providing a sort of historical shortcut through which “the present Russian common ownership of land may serve as the starting-point for communist development.” [p. 76, emphasis added; page citations omitted and punctuation altered accordingly.]

Given Edwards and Leiter’s awareness and clear understanding of Marx’s view, it is simply inexplicable to me that they think that “Marx’s theory of historical materialism” implies that China needed (or now needs) capitalist relations of production and that support for the economic policy of a faction of China’s capitalist ruling class is warranted. Of course, Edwards and Leiter may not share Marx’s world-revolutionary perspective and, if they do not, I can certainly understand why they themselves favor the establishment and development of capitalism in China. But the implications of Marx’s theory of historical materialism and their own position are two entirely separate things.

3. What Matters in Marx’s Diagnosis of Capitalism

I noted earlier that Leiter called Huemer’s post on the “irrationality” of Marxism a “sophomoric attack” and said that Huemer literally didn’t know what he was talking about. Nonetheless, Leiter agreed with Huemer that the so-called “labor theory of value” should be “abandoned”! This is also a prominent theme in Edwards and Leiter’s chapter on Marx’s economic thought, which is unfortunate, since they (like Huemer) know little about the subject they’re discussing.

Michael Huemer

The issue is important because, as Edwards and Leiter acknowledge, if we abandon the labor theory non grata, we also have to abandon Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory (p. 126, p. 140) as well as his theory of the origin of profit (p. 118)—the theory that capital’s exploitation of workers (extraction of surplus labor) is the source of all property income (profit, interest, rent, etc.). But to Edwards and Leiter, the collapse of these central pillars of Marx’s critique of political economy is unimportant, because these pillars weren’t part of “what matters in Marx’s diagnosis of capitalism.” They opine that, after we abandon the labor theory non grata, “what matters in Marx’s diagnosis of capitalism remains intact” and, in particular, that “the core ideas of historical materialism … are not affected at all” (p. 97).

But what criteria do they employ to decide what matters? That is unclear to me. It is even unclear that they are employing criteria at all, instead of merely telling us what matters, subjectively, to them.

In any case, their conclusions regarding what matters (like the conclusions of many others) tell us much more about them than they tell us about Marx. I mean this quite literally: Edwards and Leiter decline to discuss Marx’s view of what matters in his diagnosis of capitalism, which sometimes differs radically from their view. For example, Marx said, and said again (see p. 104), that his law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit is “the most important law” of political economy. “[G]iven the great importance that this law has for capitalist production, one might well say that it forms the mystery around whose solution the whole of political economy since Adam Smith revolves” (Capital, vol. 3, p. 319 of Penguin ed.).

One reason the law is so important to capitalist production is that the falling tendency of the rate of profit leads indirectly to recurrent economic crises and downturns, which in turn restore “equilibrium” and thereby allow economic expansion to resume. This “violent destruction of capital not by relations external to it, but rather as a condition of its self-preservation, is the most striking form in which advice is given it [capital] to be gone and to give room to a higher state of social production.”

My point is not that an author’s view of what is important in their work is dispositive. I just think that readers deserve to be informed about the author’s view, and about differences between it and commentators’ views, and about the reasons for these differences. Was the author just plain wrong? Or are the differences regarding what matters rooted in different interests, aims, politics, philosophical commitments, and so forth?

Edwards and Leiter’s contention that “the core ideas of historical materialism … are not affected at all” by the abandonment of the “labor theory of value” is something I have a lot of difficulty understanding, much less accepting. One conclusion that Marx drew from history is that conflict between forces and relations of production leads to the supersession of one social formation by a “higher” one. But on what grounds did Marx maintain that this conclusion applies to the future, not just the past? One justification clearly seems to be the falling-rate-of-profit theory that flows from his value theory.

The tendency for the rate of profit to fall is “simply the expression, peculiar to the capitalist mode of production, of the progressive development of the social productivity of labour” (Capital, vol. 3, p. 319 of the Penguin ed.; emphasis in original). Thus, specific social relations of production turn the development of the forces of production into a barrier to development, as rising productivity produces a tendency for profitability to fall, which in turn leads indirectly to economic crises and downturns—recurring episodes of self-destruction through which capitalism preserves itself. And since the system’s self-destructiveness is an expression of the contradiction between the forces of production and the social relations of production that are fettering them, it is “advice [… to capital] to give room to a higher state of social production.”

Let us also consider what Edwards and Leiter say about the source of profit. They agree with Marx that “capitalists have only one aim: profit” (p. 141), but they reject his claim that the source of this profit is the extraction of surplus labor in capitalist production, since this claim follows directly from the labor theory non grata. Instead, they suggest that “the source of profit [… is] the capitalist’s ability to anticipate the marginal utility that will accrue to consumers from certain commodities” (p. 118). (The marginal utility of a good is the amount by which a consumer’s total utility increases—in their view—when they consume an extra unit of the good.)

Now, in a canonical statement of historical materialism that they quote, Marx wrote that “[t]he totality of [the] relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.” But for Edwards and Leiter, the “real foundation” of the whole profit-centered capitalist system is not its relations of production that result in the extraction of surplus labor. The “real foundation” is two forms of consciousness: consumers’ evaluations of marginal utilities and capitalists’ anticipation of those evaluations. How is this not an inversion of the core historical-materialist thesis that consciousness, as well as law and politics, arise from and correspond to the relations of production?

4. Is Modern Price Theory “Better”?

This section and the five sections that follow it all deal with price theory. To provide context for this discussion, I want to return to Huemer’s attack on the “irrationality” of Marxism. He wrote:

Shortly after Marx wrote, his underlying economic theory was rejected by essentially the entire field and superseded by a better theory. Virtually no one who studies the subject (outside of oppressive Marxist regimes) believes the labor theory of value anymore. Without the labor theory of value, there’s no theory of surplus value, no theory of exploitation, and thus the central critique of capitalism fails. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, read any standard text on price theory. If you learn modern price theory, you are going to agree with it, and you are going to reject the labor theory as well. It’s that clear.

It’s clear to Huemer, but it’s far from clear to me. To help readers judge whose fault that is, I note that I have learned modern price theory. I used to teach it regularly, in introductory (“principles”) and intermediate courses. And I understand it well enough to have published a paper that demonstrated that eminent mainstream (neoclassical) economists have typically misunderstood what their own theory of labor demand, the marginal-productivity theory, implies about how technological change affects employment.

Huemer is right about one thing: “If you learn modern price theory, you are going to agree with it.” I do agree with it. But I think the issue of what I’m agreeing to, when I agree with it, is far more complicated than he suspects.

I agree that the theory’s conclusions are, in the main, validly derived from its assumptions. I also agree that the empirical predictions (and retrodictions) of the theory are generally superior to those produced by guesswork and barstool economic wisdom.

But I am not thereby agreeing to any theoretical proposition about the real world that has a determinate truth value, since the neoclassical theory I’ve learned doesn’t put forward any such propositions. It gives us models that derive conclusions from assumptions. Many of the most important assumptions are demonstrably, and widely recognized to be, false (or, as economists prefer to put it, “unrealistic”). But the falsity of an assumption is never regarded as sufficient reason to reject it. Assumptions are rejected, if at all, only if the predictive power of the model containing them is, or is deemed likely to be, poor. So neither I nor the overwhelming majority of economists, including neoclassicists, agree that the assumptions of modern price theory are true propositions.[1]

Nor do I believe that modern price theory is “a better theory” than the labor theory non grata. The main thing wrong with this notion is that Huemer is attempting to force neoclassical theory into direct contradiction with Marx’s value theory. Edwards and Leiter do the same thing, and it is a main defect in their discussion of Marx’s critique of political economy.

Jamie Edwards

Neoclassical theory and Marx’s theory are extremely different, to be sure, but the differences are mostly, and perhaps exclusively, instances of incommensurability, not contradiction. There are two main kinds of incommensurability at work. First, Marx’s value theory (together with other premises) generates claims about real-world capitalism that contradict assumptions made in neoclassical models. But since the latter are not propositions judged on the basis of their truth values, as I noted above, these cases are instances of incommensurability, not of contradictory theories.[2] Second, neoclassical theory and Marx’s theory are incommensurable whenever one deals with issues or addresses questions that the other does not. Talk of “a better theory” is particularly dubious in these cases. And such cases are more common than they might appear to be, since there are important instances in which the two theories seem to be, but are not, talking about the same thing.[3]

Huemer says that Marx’s theory “was rejected by essentially the entire field” and that “[v]irtually no one who studies the subject (outside of oppressive Marxist regimes) believes the labor theory of value anymore.” Why does he think this is relevant? In context—as a prelude to Huemer telling his readers what they will and won’t agree with—these statements function as an appeal to authority. (Here’s what you should reject. You will reject it … won’t you?) Coming from a philosopher, I find that especially disheartening. I stand with another philosopher, Paul Feyerabend, who wrote (p. 16, p. 218) that “‘experts’ frequently do not know what they are talking about and ‘scholarly opinion’, more often than not, is but uninformed gossip. … General acceptance does not decide a case—arguments do.”

This is also my response to Edwards and Leiter’s (p. 105) statement that “the consensus view among Marxist economists is that there is no solution to Marx’s transformation problem (i.e., the labor theory of value fails).”[4] I recommend—to those readers who are willing to set aside, as irrelevant, the “consensus view” of the “experts” and allow arguments to decide the case—my book Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency.

5. The “Labor Theory of Value” Versus Marginal Utility: A False Opposition

Edwards and Leiter’s account of Marx’s so-called “labor theory of value” seriously distorts the theory. It also seems rather self-contradictory. They ask, “why is one dress ‘worth’ three pounds of venison?” (p. 102). They then tell us that Marx held that “we can only explain this exchange ratio in terms of the fact that the proportions of exchange represent something of comparable value” (ibid., emphasis in original). In other words, on Edwards and Leiter’s interpretation, Marx held that one dress is exchangeable with three pounds of venison, rather than two or four pounds, because the value of one dress and the value of three pounds of venison are equal. In short, commodities’ prices always equal their values.

And since, on Marx’s theory, the commodities’ values are determined exclusively by the amount of labor-time required to produce them, it follows from Edwards and Leiter’s account that “labor inputs … are … the sole determinant of price” (p. 103). In particular, they maintain that Marx claimed that “utility … is not relevant to understanding the ratios at which commodities are exchanged (e.g., one dress for three pounds of venison)” (ibid.). In other words, Marx’s theory supposedly says that neither commodities’ values nor their prices depend on utility.

This distorted account of Marx’s value theory is the main thing that enables Edwards and Leiter to create a direct contradiction between it and “neoclassical theory”: “the neoclassical economist says that what explains the exchange ratio is the marginal utility of dresses and venison for consumers, subject to the pressures of supply and demand: labor inputs, in other words, are not the sole determinant of price” (p. 103).[5]

Edwards and Leiter later acknowledge that “Marx understood that ‘market’ prices reflect ‘supply and demand,’” and that “Marx is fully aware of the role of ‘supply and demand’ in setting market prices (as opposed to production prices)” (p. 105, emphasis in original). But if Marx’s theory says that commodities’ values don’t depend on demand while their market prices do, it follows that the theory implies that commodities’ prices don’t always equal their values, contrary to what Edwards and Leiter said earlier. There is a self-contradiction here, either theirs or Marx’s. And since demand depends in part on utility considerations, there is a similar self-contradiction regarding whether utility is a determinant of price.

The actual facts are that Marx denied that prices always equal values, he denied that labor inputs are the sole determinant of prices, and he understood that demand is another determinant. He also understood that demand is sometimes a determinant of commodities’ values (and their prices of production), even though the magnitudes of these values are determined exclusively by the amounts of labor-time required to produce them. The two statements may seem to contradict one another, but they do not, as I will discuss below. My discussion will also provide, en passant, the evidence needed to substantiate the other claims I have just made.

The main reason that Edwards and Leiter say, incorrectly, that Marx held that prices always equal values, and that labor inputs are the sole determinant of price, is that they misunderstand the opening section of volume 1 of Capital. In particular, they—like a great many other interpreters, possibly the large majority—misunderstand the purpose of Marx’s inquiry into whether exchange-value is “accidental and purely relative,” or whether there also exists an “intrinsic value … inseparably connected with the commodity, inherent in it” (p. 126 of the Penguin ed.).[6] Consequently, they also misunderstand his argumentation and conclusions, and the end result is a “Marx” that said some indefensible and pretty nutty things.

Edwards and Leiter think that Marx was trying to explain why a dress exchanges for three pounds of venison instead of two or four. What he was actually doing was addressing a problem that had plagued Ricardo (see pp. 5-12) and that remained unresolved: if the price of a dress suddenly rises from $60 to $80, is this because the dress is now worth more or because money is now worth less? But this question is meaningless unless the dress and money have intrinsic values.[7] So the first thing that Marx set out to establish was that intrinsic value does indeed exist.

Thus, when he considers the equation “1 quarter of corn = x cwt of iron,” and he says that it “signifies that a common element of identical magnitude exists in” the corn and the iron, different from either of them (Capital, vol. 1, p. 127 of the Penguin ed.), Edwards and Leiter think that Marx is arguing that a quarter of corn exchanges for x cwt of iron because they are things of equal value. But Marx is not attempting to explain why a quarter of corn exchanges for x cwt of iron. He is arguing that intrinsic value exists. His point is that a quarter of corn can be considered equal to x cwt of iron only if and insofar as they are regarded as things of the same kind; this kind is what they have in common, the “common element” that exists in each of them.

Furthermore, rather than arguing that a quarter of corn exchanges for x cwt of iron because a common element of identical magnitude exists in each of them, Marx

derives the existence of intrinsic value from a postulated exchange of equivalents, not the converse. … [He] proceeds from the exchange of two equivalent commodities to derive their equality to a third thing: if“1 quarter of corn = x cwt of iron,” then a common element of “identical magnitude” exists in each. “If A, then B” does not imply “if B, then A.” [Andrew Kliman, “Marx’s Concept of Intrinsic Value,” p. 104, emphases in original.][8]

But why was Marx so concerned to establish that intrinsic value exists? I have addressed this question in detail elsewhere. Here, I offer only a couple of comments. First, as I suggested above, if value were purely relative, the concept of value would be all but meaningless. In particular, it would be impossible to make intertemporal comparisons of values (e.g., to compare a dress’s value yesterday with its value today). Marx thus wanted to defend the concept of value—rather than any specific theory of value—against the notion that value is purely relative.

Second, the “common element” or “third thing” discussion is bound up with his theory of the fetishism of the commodity developed later, in sections 3 and 4 of the chapter. When value is regarded as purely relative—merely a relation in exchange between dresses and venison, dresses and money, corn and iron—it seems to be “a relation of objects to one another, while it is only a representation in objects, an objective expression, of a relation between men, a social relation, the relationship of men to their reciprocal productive activity” (Marx, Theories of Surplus-Value, chap. XX, emphasis in original). By disclosing the presence of a “third thing,” value, hidden in exchange relations, and then establishing that the third thing’s “substance” is human labor (in the abstract), Marx laid the groundwork for his argument that value is only a representation in objects of a relation between people.

6. Marx and Neoclassicism on Demand as an Independent Variable

Edwards and Leiter “find” several contradictions between neoclassical theory and Marx’s value theory that don’t actually exist. One reason for these “false positives” may be that they misconstrue instances of incommensurability as instances of contradiction. But the main reason is that Edwards and Leiter (and, I suspect, Huemer) misconstrue important points of agreement between the two theories as instances of contradiction as well.

One factor that helps to explain their failure to discern points of agreement is the hugely successful Whiggish propaganda campaign to ratify, if not glorify, the supposed scientific advances of neoclassicism relative to the economics that preceded it. Whiggish accounts accentuate the aspects of neoclassicism that they regard as new and improved, downplay aspects that are same old, same old, and, when possible, make the latter seem to be the former. I suspect that other factors are also responsible for Edwards and Leiter’s failure to discern points of agreement, including differences between the terminologies of neoclassical and Marxian theories, their different modes of argumentation, and the different routes by which they arrive at similar conclusions, as well as Edwards and Leiter’s conflation of the marginalist authors of the 1870s with present-day neoclassicists.[9]

One relatively minor but striking example of this problem is their discussion of demand as an “independent variable.” Edwards and Leiter first put Marx’s value theory and neoclassical theory into direct opposition with one another, asking “why the value of commodities is a matter of the socially necessary labor time as opposed to their marginal utility” (p. 107, emphasis added). Immediately thereafter, they say that “for Marx, ‘demand’ is not an independent variable in this explanation” (p. 107).

They support this claim by quoting from a passage in chapter 10 of Capital, volume 3 (p. 282 of the Penguin ed.) in which Marx writes that

the “social need” which governs the principle of demand is basically conditioned by the relationship of the different classes and their respective economic positions; in the first place, therefore, particularly by the proportion between the total surplus-value and wages, and secondly, by the proportion between the various parts into which surplus-value itself is divided (profit, interest, ground-rent, taxes, etc.). Here again we can see how absolutely nothing can be explained by the relationship of demand and supply, before explaining the basis on which this relationship functions.

This is a particularly inapt passage on which to base a claim that “socially necessary labor time” and “marginal utility” are contradictory explanatory principles, or a claim that Marx was unduly dismissive of the role of demand. It is inapt because neoclassical economists agree—lock, stock, and barrel—with what Marx argues here.

First, he implies that demand is “basically conditioned” by income. This means that demand isn’t an uncaused cause; it doesn’t mean that demand isn’t an independent variable. And the idea that demand is conditioned by income is also standard neoclassical economics. Students in introductory courses are taught that income is a key determinant of demand, that changes in income affect the demand for normal and inferior goods in different ways, and so forth.

Second, Marx suggests that changes in the distribution of (business plus personal) income lead to changes in the relative demands for different things. In response to changes in the distribution of income—between profits and wages, and between businesses’ payments of interest, rent, taxes, etc., and their retained profits—there are changes in the relative demands for securities and commodities, for means of production and consumption goods, for luxuries and necessities, and so on. All this is likewise generally accepted (and established fact).

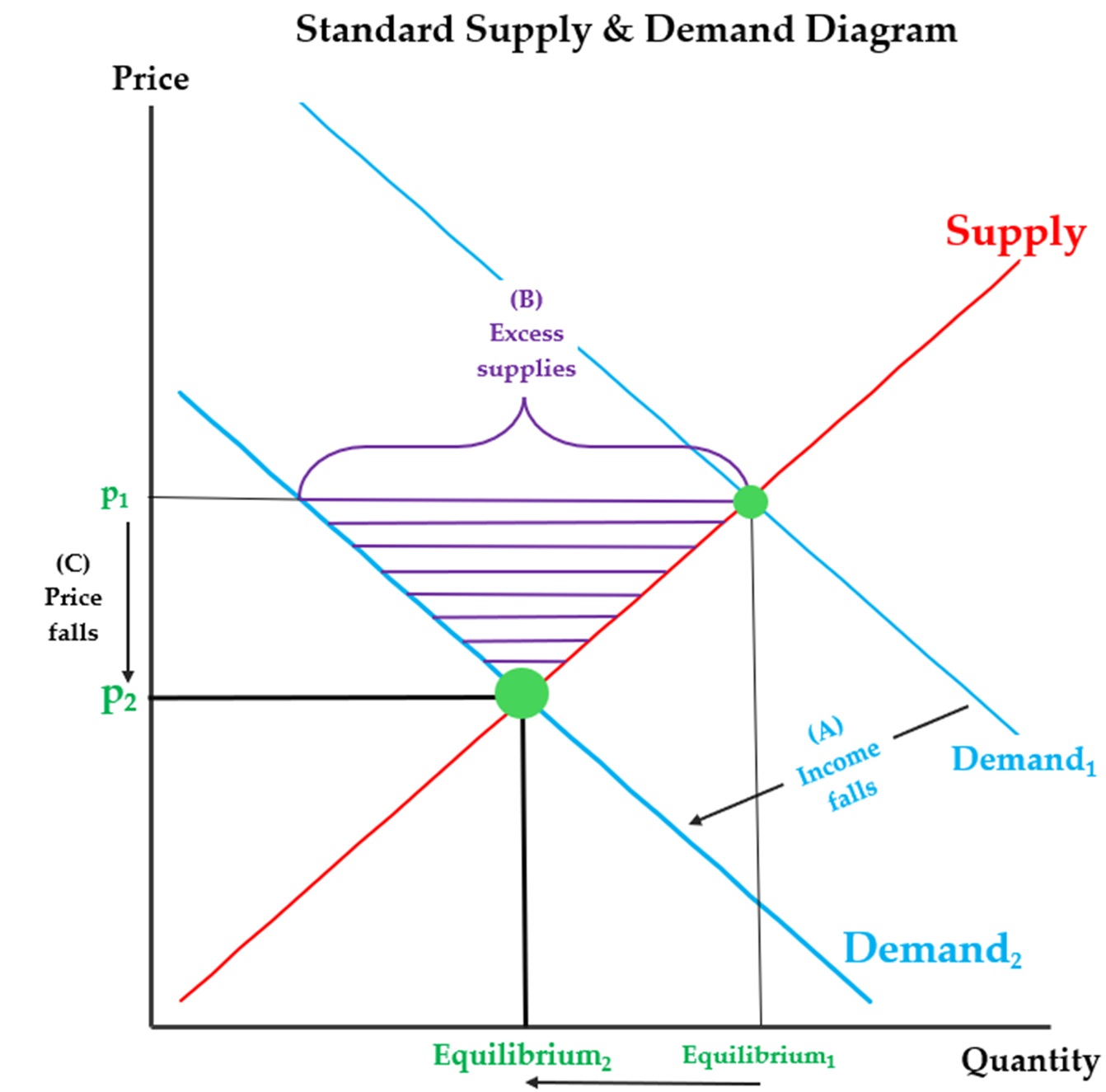

Third, Marx briefly alludes to a point he developed more fully later in this chapter and elsewhere: “the relation of demand and supply” (i.e., excess demand, excess supply, or equilibrium of demand and supply) explains only whether a good’s price will rise, fall, or remain unchanged. It cannot explain the level of the price itself. That is, it cannot explain why the price changes from p1 in one equilibrium situation to p2 in a different one, instead of changing from p1 + x to p2 – y. Once again, neoclassical economics agrees: a change in one or more determinants of demand or supply, not the state of imbalance or balance between demand and supply, is what explains why the price changes from p1 to p2 (see Figure 1, a standard supply-and-demand diagram).

Figure 1

7. Does Marginal Utility Explain Price and Profit?

Edwards and Leiter (p. 118) suggest that “the source of profit [… is] the capitalist’s ability to anticipate the marginal utility that will accrue to consumers from certain commodities.” I am not sure exactly what this means (in particular, why specify only “certain” commodities?), but it is pretty clear that they are saying that profit exists because of demand and the preferences of consumers (“marginal utility”) that underlie demand. If the demand for a thing is sufficiently strong, its price will not just cover its producers’ costs; the price will be high enough to yield them a profit as well.

This argument is not totally meritless. But it simply fails as an explanation of profit in the “long run” (i.e., mutatis mutandis) in “competitive” industries—which is the scenario that the classical economists and Marx, and modern neoclassical theories of long-run profit (or interest), have been principally concerned with.

To explain why it fails, we first need to distinguish between what Marx called average profit, the amount of profit that a firm receives when its rate of profit equals the economy-wide average rate, and surplus profit, profit in excess of average profit. Also, it will be helpful to refer to the price of production, Marx’s term for the particular price of a good that just covers its producers’ costs plus average profit.

Now imagine that the price of production of a light bulb is $3, but that some people have a thing for light bulbs and are willing to pay $15 for one. Edwards and Leiter’s marginal-utility argument explains why light-bulb producers can capture a surplus profit of $12 per bulb—momentarily. But classical economics, Marx, and neoclassical economics all agree about the following (although they use different terminologies):

If the light-bulb industry is “competitive,” additional firms can enter it freely, owing to the (definitional) absence of monopoly power, governmental restrictions, and so on. Because the industry’s rate of profit is temporarily above-average, additional firms will indeed enter it, leading to an increase in the supply of light bulbs, a fall in their price, and less surplus profit per bulb. As long as there is still some surplus profit to be gained, the process—entry, increased supply, reduced price, decline in profitability—will continue. Thus, the end result will be that light bulbs sell for $3, their price of production, and that their producers receive no surplus profit, only average profit.

The willingness of some people to pay more than the price of production (“marginal utility” in Edwards and Leiter’s sense) doesn’t explain why, when all is said and done, the price is only $3 per bulb, or why average profit remains after surplus profit has been eliminated, or why the average profit is one amount rather than another. Marginal utility does explain some things—why people who are willing to pay $15 per bulb choose instead to pay only $3 (the marginal utility of the $12 they save is positive), and why there are people willing to buy light bulbs priced at $3 (the marginal utility of these bulbs is at least $3)—but long-run price and average profit just aren’t among the things explained by willingness to pay more than the price of production.

8. Demand and the Determination of Long-run Competitive Prices

Neoclassical theory also agrees with Marx’s theory that, in a “competitive” industry that is also a “constant-cost” industry, changes in demand do not cause the product’s price to change in the long run. What “constant cost” means here is that the cost of producing the product doesn’t rise or fall when production of the product increases; and “cost” is defined here as the cost a producer pays to produce a unit of the product plus average profit. Since the product’s price of production equals the sum of producers’ costs and average profit, the constant-cost case is one in which the product’s price of production is the same (e.g., $3 per light bulb) at all levels of output.

To see why demand has no long-run effect on price in this case, consider the light-bulb industry once again and imagine that demand for light bulbs increases due to a change in some determinant of demand: income rises, or more people suddenly have a thing for light bulbs, or the price of electricity falls, or whatever. The increase in demand will certainly cause additional firms to enter the industry and cause the supply of light bulbs to increase. But as we saw above, light bulbs will sell at their price of production when all is said and done, and the price of production is a constant $3 per bulb. So the increase in demand will have no effect on the price of light bulbs in the long run.

The constant-cost case is important, because it is generally regarded as the typical case. It becomes even more typical if we restrict the analysis to reasonable variations in demand and the level of output, not extremely large ones.

I anticipate a skeptical reaction to what I have said here: surely neoclassical theory doesn’t say that long-run prices in perfectly competitive constant-cost industries are determined by costs of production and not by demand! Okay, don’t take my word for it (or call me Shirley). Consult any of the slew of neoclassical textbooks (see sections 23.3-23.5) and instructional videos on the topic. Even David Friedman’s Price Theory—which Huemer endorses (p. 12) and which is as far-right as they come and heavily laced with propaganda—admits that

the equilibrium of the industry has each firm producing at minimum average cost and selling its product for a price that just covers all costs. … Increases in demand increase the number of firms and the quantity of output, with price unaffected. We have described a constant-cost industry—one for which the cost of an additional unit of production is independent of quantity. [Chap. 9; emphasis in original.]

Although the constant-cost case is typical, increasing-cost industries are also possible. In such industries, the cost (including average profit) of producing a unit of the product—and thus, its price of production—increases as more of the good is produced. For example, if demand for light bulbs doubles, inducing entry of additional firms into the industry and a doubling of supply, the price of production may rise from $3 to $3.50 per bulb. So, in the increasing-cost case, changes in demand do affect the price of light bulbs in the long run.

However, this clearly does not imply that their price is determined by demand rather than by costs of production. The long-run price of light bulbs rises from $3 to $3.50 per bulb precisely because the cost of production, inclusive of average profit, rises from $3 to $3.50 per bulb. The long-run price continues to be determined exclusively by the cost of production, in the sense that the only factors that affect the price are those that affect the cost of production, and they affect the price only insofar as they affect the cost of production, not otherwise. Demand is among those factors in the increasing-cost industry case, but not in the constant-cost one.

Once again, this is both what neoclassical theory says and what Marx said. In chapter 10 of Capital, volume 3, he considered the case in which the different producers of a product have different technologies: they produce the product “under the worst conditions,” or “average” ones, or “the most advantageous ones” (p. 279 of the Penguin ed.) Consequently, their costs of production differ as well. When demand is low, only low-cost producers can compete successfully in the market, so the industry-average cost of production will be low, and thus the product’s value (and price of production) will be low. But as demand rises, average-cost and even high-cost producers can compete successfully, so the industry-average cost of production, and thus the product’s value (and price of production), will rise as well.[10]

Brian Leiter

Not only did Marx say that demand can influence a product’s value (and price of production), but he said it precisely where Edwards and Leiter tell us he was saying the opposite. As I discussed above, they claim that Marx argued that “‘demand’ is not an independent variable in th[e] explanation” of “why the value of commodities is a matter of … socially necessary labor time” (p. 107). The passage they quote to support this claim comes smack in the middle of chapter 10’s discussion of when and how changes in demand affect commodities’ values and prices of production!

In sum, the attempt to counterpose labor-time and costs of production to utility and demand—to turn them into mutually exclusive, contradictory determinants of commodities’ values (and prices of production)—is wrongheaded. It falsifies the history of economic thought, and, as economic theory, it doesn’t get out of the starting gate.

9. On Sweezy’s View of What Explains Prices of Production

Edwards and Leiter claim that “the labor theory of value cannot explain the production prices of commodities” (p. 105). They appeal to Paul Sweezy’s Theory of Capitalist Development to support this view, but they seriously misunderstand what Sweezy was arguing, which was very different from what they are arguing. They write:

the consensus view among Marxist economists is that there is no solution to Marx’s transformation problem (i.e., the labor theory of value fails). We can agree with Sweezy that if what we want to understand is only “the behavior of the disparate elements of the economic system (prices of individual commodities, profits of particular capitalists, the combination of productive factors in the individual firm, etc.),” then neoclassical “price theory [marginal utility theory] … is more useful in this sphere than anything to be found in Marx or his followers” … We may, in short, adjudge the Marxian attempt to solve the “transformation problem” a failure: the labor theory of value cannot explain the production prices of commodities. [P. 105. The interior quotes come from p. 129 of Sweezy’s book; the insertion in square brackets is Edwards and Leiter’s.]

Edwards and Leiter are suggesting, and come close to saying explicitly, that they and Sweezy agree that (1) the “labor theory of value” fails because it cannot explain prices of production, and (2) prices of production are explained better by “marginal utility theory.”

However, Sweezy did not accept (1). His view, expressed six pages earlier, was that Bortkiewicz’s “correction” of Marx’s account of the transformation of values into prices of production “show[s] that a system of price calculation can be derived from a system of value calculation” and that Bortkiewicz’s “correction” is therefore the “final vindication of the labor theory of value, the solid foundation of [Marx’s] whole theoretical structure” (p. 123). This is a strange view, and clearly false in my opinion, but it was indeed Sweezy’s view.

As for (2), it doesn’t make much sense to argue that “marginal utility theory” is particularly useful when explaining prices of production, since they are determined by costs of production and the economy-wide average rate of profit. Utility considerations are much more salient to the explanation of market prices that deviate from prices of production due to demand exceeding or falling short of supply.

And Sweezy was not affirming (2) in the statement that Edwards and Leiter quote. He was acknowledging that “the whole set of problems concerned with value calculation and the transformation of values into prices is excess baggage” (p. 128), while neoclassical price theory is especially useful—in some contexts but not in others. If one is concerned only with “the behavior of the disparate elements of the economic system” rather than with “the analysis of the behavior of the system as a whole” (p. 129), then value calculation is excess baggage. But an understanding of “the system as a whole” is certainly needed to explain the magnitudes of prices of production, since they are determined in part by the economy-wide average rate of profit. And if the system as a whole is one’s concern, Sweezy went on to argue, “there is no way of dispensing with value calculation and the labor theory of value” (p. 130).

One possible source of Edwards and Leiter’s confusion here is inadequate understanding of what prices of production are, and thus, of what the transformation of commodities’ values into their prices of production is. They tell us that “the production price is the price of a commodity given the costs of production (raw materials, technology, and labor), and assuming some rate of profit for the capitalist” (p. 105). This definition provides little help, since capitalists would also obtain “some” rate of profit if their products were to sell at their values, at market prices, at monopoly prices, at regulated prices, and so on.

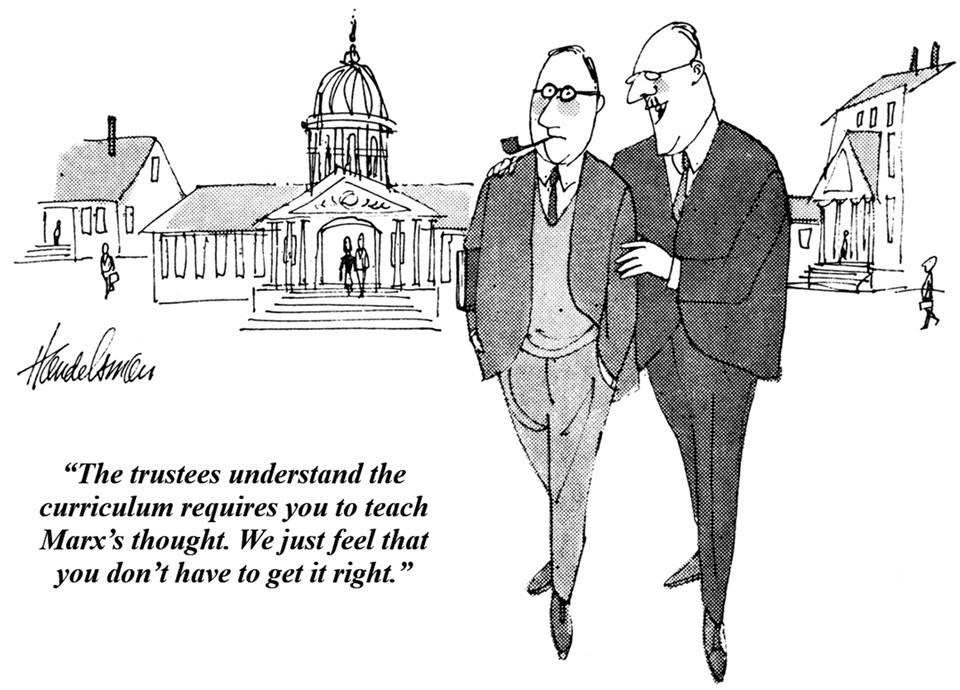

Adaptation of 1965 cartoon in Punch magazine by J.B. Handelsman

Even worse, Edwards and Leiter confuse and conflate commodities’ values with their prices of production, which leads them to claim, incorrectly, that Marx held that commodities tend on average to sell at their values, rather than at their prices of production. “Marx … adopts Smith’s metaphor of the value (the ‘natural price’) of a commodity as the ‘centre of gravitation’ … around which the market prices revolve” (p. 105). “[W]hat Marx calls ‘the law of value’” is the proposition that, “in a well-functioning marketplace, commodity prices gravitate towards their values—i.e., the socially necessary labor time to produce them” (p. 106).[11]

But if commodities tend on average to sell at their values, what is the meaning of the statement that values are transformed into prices of production? What is the difference between the values and these prices into which they are transformed? Edwards and Leiter do not say. They tell us that “Marx’s labor theory of value cannot explain production prices” (p. 109), but because they lack a clear definition of prices of production, and confuse and conflate them with values, they do not and cannot answer the question, “What is it, exactly, that requires explanation?” In the absence of an answer to that question, the conclusion that the theory cannot “explain” prices of production has little meaning.

Edwards and Leiter’s primary justification for their conclusion is the idea that “marginal utility theory” is what explains prices of production. But they provide no independent argument that this is true, so their secondary justification—the appeal to Sweezy—is the operative one. Yet Sweezy didn’t say anything even remotely like what they think he said, and “the consensus view among Marxist economists” regarding the relation between values and prices of production likewise has nothing to do with the supposed superiority of “marginal utility theory.”[12] So although Edwards and Leiter conclude that the labor theory non grata can’t explain prices of production, they provide no actual justification for this conclusion at all.

Here is my answer to the question, “What is it, exactly, that requires explanation?”:

- how prices of production differ from values;

- why commodities tend to sell on average at their prices of production rather than at their values;

- how average profit is determined, and thus, how the magnitude of a commodity’s price of production is determined; and

- how, despite the differences between values and prices of production, the latter are transformed forms of value, not self-subsistent entities unrelated to it.

Marx’s value theory explains all this, in a logically coherent way, even though his critics’ misinterpretations of the theory make it internally inconsistent.

10. The Physicalist Alternative to Marx’s Concept of Capitalist Exploitation

In Marx’s work and subsequent economic theory, the term exploitation pertains to a disproportion between what is contributed and what is received. Individuals and classes are considered exploited if they are required, by force or circumstances, to contribute more to some process than they receive in return.

Marx held that workers are exploited in the sense that they are made to perform surplus labor and thereby to create surplus-value (or profit)—an amount of new value that exceeds the value of their wages and benefits. Edwards and Leiter (p. 118) note, correctly, that “Marx’s technical notion of exploitation deriv[es] from the labor theory of value,” and that this notion of exploitation therefore “falls apart” if Marx’s value theory isn’t correct.

However, they contend that “[o]ther senses of ‘exploitation’ … would remain intact” (p. 118), and they go on to offer an alternative argument as to why workers are exploited. Their argument is basically the same as the physicalist argument put forward by G.A. Cohen and endorsed by Ben Burgis, the so-called “Plain Argument.” Rather similar physicalist arguments have long been made by Sraffian and Sraffian-adjacent Marxist economists (see also chap. 10 of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”).

Like Cohen, Edwards and Leiter eschew the key tenet underlying Marx’s conclusion that workers are exploited, namely that workers’ labor is the exclusive source of new value. However, they try to reach the same conclusion by mimicking Marx’s argument but substituting production of physical products for creation of value. This substitution simply doesn’t work, as the following will make clear.

Edwards and Leiter (p. 114) endorse Sweezy’s statement (p. 129) that “[t]he entire social output is the product of human labor. Under capitalist conditions, a part of this social output is appropriated by that group in the community which owns the means of production.” And they rephrase the statement as follows: “In short, owners of capital accrue most of their wealth only because of the work of those who only own their labor power: that is the basic fact of capitalist society, quite independent of the labor theory of value” (p. 114, emphasis added). Later (p. 118), they provide a more complete explanation of what they mean:

Consider that the workers in the auto plant produce cars that sell for much more than the workers are paid: some of that “profit” goes to the “owners” of the factory who do little or no work at all. … most … wealth goes to those who do not do any actual work, while those doing the actual work in the factories and warehouses and service industries are paid only a small portion of the wealth they generate. Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, does not produce any of the daily value of Amazon by his own efforts; the heirs of the founder of the Walmart chain of retail stores in the United States do no work at all, but are “billionaires” because of the work done by employees of the chain of stores their father started.

The problems here begin with Sweezy’s statement, which is technically correct but misleading. Although the entire social output is the product of human labor, it is also the product of nonlabor inputs. Physical output is not produced by labor alone, but by labor in conjunction with the various nonlabor inputs (land, machinery, materials, etc.) that are needed in every production process.

In addition, although only human labor and nonlabor inputs directly produce products, a fuller list of the people, things, and entities that contribute to the production of the social product would include at least:

- workers;

- nonlabor inputs;

- entrepreneurial capitalists, who make investment decisions, organize production, and so on;

- governments, which provide a legal framework within which production can take place;

- suppliers of nonlabor inputs, who make inputs they own available for use in production; and

- lenders, who make funds they own available for use in production.

The fuller list is relevant because exploitation is a disproportion between receipt and contribution, not receipt and direct production of products. After all, many instances of exploitation have nothing to do with production. For example, a business that defrauds its customers exploits them, because it receives a certain amount of value from them but gives them only things of lesser value in return.

The preceding remarks enable us to spot the defects in Edwards and Leiter’s argument. They claim that the capitalist class obtains its wealth “only because of” workers’ labor. They clearly don’t mean that workers’ labor is the exclusive source of surplus-value (profit)! So “only because of” might mean that, to produce physical wealth, only human labor is needed. But that is obviously false, so “only because of” apparently means that workers’ labor is necessary—without it, there would be no physical wealth for the capitalist class to amass.

This is true, but nonlabor inputs are also always necessary and, in capitalism, items 3-6 of the fuller list are generally necessary as well. So if the point is that X is exploited if X makes a necessary contribution to physical production but receives less than the total product in return, then all items 1-6 in the fuller list are exploited. Moreover, all talk about exploitation is pointless, because there is no alternative to exploitation. Since the legitimate claims on the product exceed the actual product many times over, a nonexploitative distribution of the product is impossible in principle.

Thus, the facts that Edwards and Leiter have asked us to consider need to be reconsidered, this time without the unwarranted privileging of workers and work:

the nonlabor inputs in the auto plant produce cars that sell for much more than the suppliers of these inputs are paid: some of that “profit” goes to the “owners” of the auto company that buys the inputs, who rarely if ever directly produce cars at all. … most … wealth goes to those who do not provide a legal framework within which production can take place, while the governments that provide such a framework for the factories and warehouses and service industries receive tax payments equal to only a small portion of the wealth they help to generate. Amazon’s workers do not produce any of the daily value of Amazon by their own efforts alone; Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, contributes to production by making inputs he owns available for use in production, and Amazon workers have jobs and income only because he does; the heirs of the founder of the Walmart chain of retail stores in the United States do not directly produce at all, but are “billionaires” because of the entrepreneurship and investment decisions of their father and the contributions to Walmart production provided by workers, governments, nonlabor inputs and their suppliers, and lenders.

Given this multiplicity of contributions and contributors to physical production, there is only one way for a physicalist argument to justify the charge that capitalists exploit workers. It needs to deny the facts and assert that only workers and their labor contribute to physical production.

It never ceases to amaze me that intelligent people, who gasp in horror at the monocausal and “unfalsifiable” idea that labor is the exclusive source of new value, blithely put forward, time and again, arguments that turn out to depend crucially on the equally monocausal and demonstrably false idea that labor is the exclusive source of new physical products!

G.A. Cohen

Leiter has written perceptively about why Marxism doesn’t need morality-based political philosophy and about how G.A. Cohen’s turn toward such philosophy went hand-in-hand with his rejection of historical materialism and the revolutionary potential of the working class. I agree with what Leiter says about Cohen, and I want to add only that Cohen’s turn toward morality-based political philosophy was also bound up with his rejection of Marx’s value theory.

In 1983, four years after his “Plain Argument” paper was published, Cohen addressed an objection made by “apologists for capitalism [who] deny that capitalists are exploiters on the ground that they contribute to the creation of the product by providing means of production” (p. 316, emphasis added). In other words, capitalists are suppliers of nonlabor inputs. On the standard (contribution vs. receipt) definition of exploitation employed in the “Plain Argument” paper, the existence of such contributions by capitalists is fatal to the argument’s conclusion that capitalists exploit workers. Unable to deny that capitalists do make these contributions, but unwilling to abandon the argument’s conclusion, Cohen changed his definition of exploitation.

For someone to qualify as an exploiter according to his new definition, it is no longer necessary that he receives more than he contributes. Exploitation becomes purely a matter of immoral property relations:

The question of exploitation …. resolves itself into the question of the moral status of capitalist private property. … [T]he said “contribution” does not establish absence of exploitation, since capitalist property in means of production is theft, and the capitalist is therefore “providing” only what morally ought not to be his to provide. [Ibid.]

Thus, Cohen’s turn to morality-based political philosophy was due in part to his dislike of Marx’s value theory, his desire to construct a theory of exploitation that isn’t based on it, and his recognition that his physicalist “Plain Argument” was not a sound alternative to Marx’s argument.

11. The Underconsumptionist Theory of Crisis

After rejecting Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory, Edwards and Leiter (p. 126) discuss “Marx’s more promising explanation for why capitalism will enter a serious ‘crisis’ […, which] does not depend on the labor theory of value at all.” The explanation to which they refer is the underconsumptionist theory of capitalist economic crisis. But is it more promising? And was it in fact Marx’s explanation? To answer these questions, we first need some background information.

Background

All economic downturns—which is mainly what is meant by “crises” here—are characterized by a lack of demand for goods and services. The theoretical question is, what causes the lack of demand? Inadequate demand and inadequate consumption (underconsumption) are not the same thing, since consumption demand (demand for consumer goods and services) is only one part of total demand. Investment demand (demand for machinery, equipment, construction of buildings, and so on) is the other part.

The underconsumptionist theory says, and Marx clearly said, that the consumption demand of the masses is restricted under capitalism because of their relative poverty. But the differentia specifica of underconsumptionist theory is a further claim: that limits on consumption demand ultimately cause investment demand to be strictly limited as well; in the long run, investment demand cannot grow more rapidly than consumption demand.

Thus, according to underconsumptionist theory, total demand is constrained, which leads to a chronic, structural tendency for total demand to fall short of total supply (production of consumption and investment goods and services). Such a situation is, however, unsustainable in the long run. If supply exceeds demand, an “overproduction crisis” must be the result. Either production and employment must decline, or prices must fall, or some combination of the two.

A simple example may help to bring the issue into sharper focus. Imagine that total supply is $100 but consumption demand is only $80. No downturn will occur, despite the limited consumption demand, if investment demand is at least $20. But assume that investment demand falls from $20 to $15. Total demand is now only $95 while total supply is $100, so a downturn will occur. The question is why it occurs.

Underconsumptionist theory maintains that, while “external stimuli” temporarily boosted investment demand, it is ultimately constrained by limited consumption demand, so it had to, and did, fall back to its normal long-run level (equal in this case to 15/80ths of the level of consumption demand). If, however, limited consumption demand does not constrain investment demand, then underconsumptionist theory is wrong about the cause of the downturn.

The actual cause(s) might be one or more other factors that make inadequate total demand the normal long-run state of the economy. Either that, or inadequate total demand is not the economy’s normal long-run state. In other words, it would have been possible, in principle, for investment demand to remain at the $20 level, but a change in one or more of its determinants—a fall in profits, tighter credit conditions, other financial difficulties, weaker expectations of future demand, higher input costs, higher business taxes, past overinvestment, an accidental exogenous “shock,” and so on—has caused it to decline temporarily (which does not imply that the decline is accidental or one-off).

More promising?

Edwards and Leiter contend that limited consumption demand does, in fact, strictly constrain investment demand in the long run. Why? Clearly, the volume of consumption demand is a major influence on investment in industries that produce consumption goods and services. But as Edwards and Leiter (p. 131) correctly note, “not all commodities are sold to ordinary consumers: many capitalists produce commodities (e.g., computer or automotive parts) for sale to other capitalists, not consumers.” On average, such production constitutes 48% of net output in the US.

So the issue is whether limited consumption demand constrains investment in industries that produce investment goods and services. (If it doesn’t, then it also doesn’t constrain total demand.) Edwards and Leiter (p. 131, emphasis added) say that it does constrain such investment, because “capitalists who primarily sell their commodities (e.g., computer parts or automotive parts) to other capitalists will eventually be affected by a decline in consumption of the downstream commodities aimed at consumers for which those parts are utilized.” In other words, all production is ultimately production for the sake of consumption, production “aimed at consumers.” Computer parts are used to produce computers, which are used to produce machine tools, which are used to produce auto parts, which are used to produce cars, which are used to provide taxicab services, which—finally, thank God!—have to be sold to “ordinary consumers.”

But is this true? Is all production a one-way flow from “upstream” to “downstream”?

Why can’t businesses ultimately sell to each other, instead of to people? For instance, why can’t there be a process in which mining companies sell iron to companies that use the iron to make steel; and the steel producers sell the steel to companies that use the steel to make mining equipment; and the mining-equipment producers sell the mining equipment, not to the iPod and shoe producers, but to the mining companies that then use the equipment to mine more iron, … and so on and so forth? (Of course, I am not referring to a system without any production of consumer goods, just one in which production of consumer goods and the demand for them rise less rapidly than production of and the demand for investment goods.) [Andrew Kliman, The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession, p. 161, emphasis in original.]

In fact, the claim that the expansion of capitalist production must eventually be held back by limited consumption demand is false. Its falsity was first demonstrated by Marx’s reproduction schemes in Capital, volume 2 (which Edwards and Leiter do not discuss). The schemes show, first, that one part of the economy’s output does in fact consist of means of production that will be used to produce additional means of production, which themselves then produce even more means of production, and so on. Second, they show that the growth of this part of output is not constrained by limited consumption demand, since its purchasers are always companies, never people. Third, they show that an increase in the rate of economic growth generally requires an expansion of this part of output in relation to the total.

Edwards and Leiter do not address these objections. Others have done so, but I have argued (pp. 161-162, 164, 167-173) that they fail to answer the objections successfully.

Marx’s Explanation?

Edwards and Leiter’s evidence that the underconsumptionist theory of capitalist economic crisis was Marx’s explanation consists of one paragraph in chapter 15 of volume 3 of Capital, and perhaps another paragraph, in chapter 30 of the same volume (pp. 352-353 and pp. 614-615 of the Penguin ed., respectively). Both paragraphs indicate that consumption demand is constrained under capitalism because of the relative poverty of the masses. But neither actually indicates that Marx had an underconsumptionist theory of crisis.

The first of the two paragraphs notes that “antagonistic conditions of distribution … reduce the consumption of the vast majority of society to a minimum level.” Consequently, it suggests, there is a gap between total supply and consumption demand. But Marx, unlike underconsumptionist theory, suggests that the gap can be filled, and that investment demand is what fills it: “The market, therefore, must be continually extended …. The internal contradiction [between production and consumption] seeks resolution by extending the external field of production.” Investment is clearly what allows production to expand (to be “extend[ed]”), and given the restricted volume of consumption demand, it has to be investment that extends the market. Of course, additional production resulting from additional investment causes the gap between total supply and consumption demand to increase further, as Marx notes, but he does not deny that investment demand can continue to fill the gap.

Edwards and Leiter do not provide an alternative interpretation of the two sentences that refer to the extension of the market and production. They quote and discuss portions of the paragraph, but not these sentences.

The second of the two paragraphs is underconsumptionists’ all-time favorite, because its concluding sentence says that “[t]he ultimate reason [letzte Grund] for all real crises always remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses.” Thus, there seems to be at least one statement by Marx that not only acknowledges that underconsumption is a fact but also bases a theory of crisis on it. The leading underconsumptionist of the twentieth century, Paul Sweezy, wrote (p. 177) that it “appears to be Marx’s most clear-cut statement in favor of an underconsumption theory of crises.”

However, if we read the concluding sentence in context, Marx is saying something quite different: the poverty and restricted consumption of the workers are the “ultimate reason” for crises in the sense that they make crises possible. If workers received all of society’s income, a crisis—that is, a shortfall in demand—would be impossible, because the workers would spend all of their income on consumption goods and services.[13] But in actual fact, workers receive only part of the total income (and thus suffer from poverty and restricted consumption). The rest of society’s total income is received by capitalist companies, members of the capitalist class, and third parties, and it is possible that they do not spend all their income on (consumption and investment) goods and services. If they do not, then there will be a shortfall in demand (i.e., a crisis).

Thus, the paragraph argues that crises become possible when and because nonworkers receive part of society’s total income. But it does not discuss the conditions that turn this possibility into an actuality. And it does not even hint at the idea that inadequate consumption demand leads to a chronic tendency for total demand to fall short of total supply, or the idea that investment demand is constrained by limited consumption demand. (For a more detailed analysis of the paragraph, see pp. 166-167 of The Failure of Capitalist Production.)

Interestingly, Edwards and Leiter regard the paragraph as potentially problematic for underconsumptionist crisis theory, since much of it deals with the fact that the consumption demand of the masses isn’t the only component of total demand:

So why then does Marx nonetheless claim … that the “ultimate reason for all real crises remains the poverty and restricted consumption of the masses”? As capitalists purge from the payrolls those who have only their labor power to sell, and replace them with technology, consumption by the non-productive classes would continue. Why should a “crisis” ensue? [p. 131].

Their answer is that

in a society where most people are selling their labor power to capitalists, the disappearance of that class would result in a massive decline in consumption of commodities. Moreover, insofar as the non-productive classes are dependent on workers who sell their labor power, their consumption power will ultimately be affected as well: this will be especially true of the state, to the extent it depends on taxes not only on the income of those who sell labor power but also of those non-productive people (e.g., service professionals, artists, ministers) who depend on either selling their services to workers or who depend on their voluntary financial support. Even capitalists who primarily sell their commodities (e.g., computer parts or automotive parts) to other capitalists will eventually be affected by a decline in consumption of the downstream commodities aimed at consumers for which those parts are utilized. [p. 131]

This answer simply isn’t an interpretation of the paragraph that Marx wrote. The answer and the paragraph have almost nothing in common.[14] In fact, I don’t think that Edwards and Leiter are even trying to interpret the text here; the aim of their answer is instead to explain away the implications of the fact that workers’ spending isn’t the sole component of demand. But if the answer is not an interpretation, then neither is its underconsumptionist conclusion. In other words, even Edwards and Leiter are not construing the paragraph as evidence that Marx had an underconsumptionist theory of crisis. Instead, they are assuming that he did and trying to reconcile the text with that assumption.

Notes

[1] And insofar as its conclusions pertain to the real world, they are hypotheses, not declarative propositions.

[2] For example, Marx’s law of the increasing concentration and centralization of capital (Capital, vol. 1, chap. 25, sect. 2), which is based partly on his value theory, contradicts core assumptions of neoclassical models of perfect competition, but no neoclassical economist accepts that increasing concentration and centralization falsify neoclassical theory. Neoclassicists will acknowledge only that perfect competition is “unrealistic,” while continuing to assume it when they desire (generally for instrumentalist reasons).

[3] For example, Marx’s theory says that the source of interest is workers’ surplus labor while a different theory says that interest is compensation received in return for abstaining from consumption. In Marx’s view, with which I concur (see pp. 208-209), the theories are answers to two different questions.

[4] Appeals to the consensus views of “Marxist economists” and astrologers differ in kind from appeals to the consensus views of physicists and medical researchers. Because there are protocols in certain fields that tend to weed out error, what can seem to be appeals to authorities in those fields are (often) implicitly appeals to evidence—that is, to the support for authorities’ claims provided by tests that have employed effective protocols. But “Marxian economics” isn’t among those fields.