Meeting with Benny Wenda, a Leader of the Independence Movement, Recalls the Struggles in East Timor and Aceh

by Anne Jaclard

Brenda Wenda spoke in New York City on Feb. 6 during his world tour to gather support for the West Papuans’ demand that Indonesia cease its human rights abuses and allow a referendum on their future status. Wenda has been fighting nearly all his life against Indonesia’s brutal subjugation of the people of West Papua. Forced to live in the jungle as a child in order to escape the Indonesian assaults on Papuan villages, he became a leader of the independence movement that is struggling to end Indonesia’s repression, its slaughter of the indigenous people, and its destruction of their unique environment.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed over 50 years in the two provinces comprising West Papua (Indonesia split it into two in 2003, hoping to weaken unity among the disparate tribes of people). Multinational mining companies, most notoriously Freeport McMoRan based in Arizona, have raped the land while extracting its valuable resources, especially gold and copper. Others took away the natural gas and timber, all with the aid of the Indonesian military to silence protests.

At the meeting in New York sponsored by East Timor Action Network, Wenda declared, “Our movement is for independence and for our forests and mountains and land.” He described conditions in his country, which he likened to Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor (now Timor-Leste) from the time of it was invaded by Indonesia in 1975, until it won independence in 1999, during which period hundreds of thousands of East Timorese died.

Jail, Torture, Escape

Wenda was jailed in 2002 for leading a peaceful demonstration for self-determination. After about a year, during which three other West Papuan leaders were murdered while in prison, he managed to escape, and fled Indonesia. He told us how he was tortured in prison, handcuffed and shackled for an entire two weeks—and showed us the scars on his ankles, and how he was fed through narrow ventilation holes in the door. How did he pass the time? He composed a song, which he played for us on the small Papuan guitar that he carries everywhere he speaks.

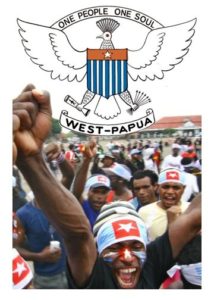

Since escaping prison, Wenda has lived in Britain, where he works with the Free West Papua Campaign, http://www.freewestpapua.org/ (His own website is http://www.bennywenda.org/ ; another informative site run by two Americans is http://akrockefeller.com/ The pictures below are from Wenda’s site.)

Wenda described how total the repression is: anyone with long hair or a beard is suspect and gets beaten. His brother was arrested and tortured without having done a thing. West Papuans are supposed to bow when they walk past a military post; one man who failed to do so was chased after and killed, just for that. Decent jobs go to transmigrants (non-Papuans from other parts of the country), while Papuans are not even permitted to ride on the public buses.

In spite of the severity of the repression—for holding up a sign that demands a referendum, you get three years in prison–Wenda spoke optimistically about the survival and ultimate victory of the movement for self-determination. In the past three years, he said, more and more young people have become active in the movement, communicating through social media (books about the history of the movement are banned). The youth have been conducting peaceful demonstrations in both West Papua and the capital city, Jakarta, where they have been joined by Indonesian students.

Tour Seeks International Support

Wenda recently spoke at the United Nations and at the British and Scottish Parliaments, but no sooner had he left New York to speak at the Parliament of New Zealand, when that body banned his appearance. Indonesia is a huge economic and military power in that region, and we can guess that New Zealand, like other nearby countries, is afraid to cross it. In contrast, a grass-roots movement in Australia managed to force that country to give some support to East Timor in the final years of its struggle for independence.

Indonesia receives millions of dollars in military and other aid from the U.S., which also trains special “counterinsurgency” units of its military and police. It has long been an outpost for U.S. influence and now is considered a bulwark against political Islam. The U.S. was complicit in Indonesia’s occupations and repression in West Papua as well as East Timor and Aceh.

Indonesia invaded West Papua in 1962 and annexed it in 1969, following a fake referendum engineered by the United Nations with the backing of the U.S. After the Indonesian army terrorized the population—some whole towns were massacred–just 1,025 people were allowed to vote, out of a population of close to a million. One voter was Wenda’s father, who was taken to a polling place and forced to vote for annexation. Later, his father bravely testified in Europe that the election had been a sham. The independence movement has continued to struggle, in spite of continued repression, ever since.

The experiences of East Timor and Aceh

West Papua’s story is familiar to those of us who were active in solidarity work for the independence movements in East Timor and Aceh, another province with a long history of struggle. Aceh suffered military repression and killings for decades before a 2005 compromise agreement granted it some autonomy and a greater share of income from its natural resources. Its grass-roots civil society and armed movements for self-determination were unable to continue after some 200,000 Acehnese died in the tsunami of December 2004. Although there was a small solidarity movement for Aceh in the U.S., it did not achieve the influence of the earlier U.S. movement in support of East Timor, which succeeded in getting Congress to block military aid for several years.

In East Timor, Aceh, and West Papua, the Indonesian military’s power structure exercised and extended its influence through its treatment of the rebellious provinces, strengthening the military’s political power in the national government as well. The fall of the Suharto dictatorship in 1998, brought about by mass movements for democracy, particularly the student movement, failed to oust the military from its extensive economic as well as political control throughout the country. At this very moment, two of the three major candidates for president of Indonesia in the coming election are military men who made their reputations in the above-described provincial “campaigns.”

At the meeting in New York, American and other veterans of the earlier support movements discussed with Wenda what we might do to aid West Papua and what we could expect to happen. Some thought independence would eventually be won after going through various stages of struggle, and shifts in other governments’ policies, as happened in East Timor. I suggested that we can’t know what different directions events might take, and emphasized that the best hope is a revolutionary transformation of Indonesia itself.

Today, the tiny country of Timor-Leste remains poverty-stricken, ethnically torn, and dominated by Indonesia economically. Aceh province is internally divided, with limited autonomy, continued violence, and official religious discrimination against women. When I asked Wenda what kind of future society the Papuans want, he only answered “self-determination.”

Wenda acknowledged past problems in the independence movement due to tribal rivalries. The Indonesian policy of promoting extensive transmigration, he said, now places the Papuans in danger of becoming a minority in their own land, so that even independence might not bring them self-determination. Ironically, he said, this threat has caused increased unity within the West Papua movement among its different tribes and factions. In spite of West Papua’s vastly different history from East Timor’s, he regards independence as a realistic goal—and possibly the only hope for the survival of West Papuans as a people.

Very disappointing to see MHI support bourgeois “national liberation” struggles.

Perhaps Schalken’s comment is a sick joke, a parody of certain Old Left views? I fail to see how an ethnic group who are fighting for their very survival and that of their homeland can be considered “bourgeois.” He ought to look at the history of the West Papuans’ horrific suppression and continuous rebellion that is chronicled on the websites cited in my article.

Marxist-Humanists see national liberation and other struggles for self-determination as “forces of revolution” when they become mass movements that are demanding freedom from oppression and freedom to create a new way of life for themselves. We see revolutionary impulses arising from such movements, whether of workers, subsistence farmers, youth, national minorities, women, or others; their ideas as well as actions inspire other movements to rebel as well. In fact, we consider this interaction between multiple liberatory ideas and multiple struggles to be the important history of the world since World War II, including national liberation struggles in Asia and Africa, anti-imperialist and anti-dictatorship movements in Latin America and the Caribbean, African-American and women’s liberation struggles in the U.S., and many more.

We see this dialectic of liberation as central to the prospect for thorough-going revolution that actually uproots capitalism AND goes on to establish a free society. The pre-conceived notions of some leftists of what a revolution must look like serve to stifle mass movements and ideas from developing the two-way road between theory and practice that is vital to this process.