by Andrew Kliman

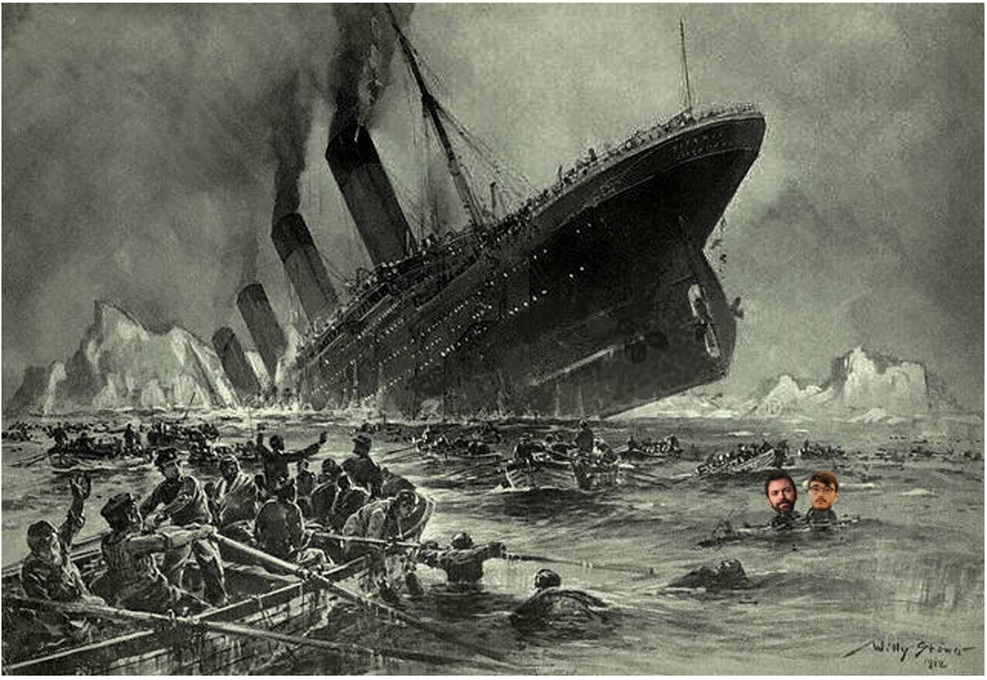

Unlike rats, who flee a sinking ship, Álvaro Romaniega chose to board the Titanic—Juan Ramón Rallo’s “titanic … destr[uction] of Marx’s economic thought”—just as it was sinking.

Featuring Juan Ramón Rallo (left) and Álvaro Romaniega (right).

(Background image: The Sinking of the Titanic, by Willy Stöwer, Magazine Die Gartenlaube.)

Can the Exchange Process Alter the Amount of Value in Existence?

My May 15 response to Rallo’s “Reply to Andrew Kliman” focused on Marx’s demonstration, in chapter 5 of Capital, volume 1, that “when commodities exchange at prices that differ from their values, this changes only the distribution of the already-existing value; it does not alter the total amount of value in existence.” My reply also focused on the key implication of that demonstration, Marx’s aggregate value-price equalities (the equality of the total price and total value of output; of total profit and total surplus-value; and of the “price” and “value” rates of profit). I emphasized that

the aggregate value-price equalities follow inevitably—without exception—from Marx’s account of the value-price transformation (as understood by the TSSI) and his demonstration in chapter 5 of Capital, volume 1. No special cases whatsoever can yield a contrary result. [Emphasis in original.]

But I also emphasized that

I am not saying or implying that nothing can yield a contrary result. In principle, it would be possible to overturn the aggregate value-price equalities by disproving Marx’s demonstration in chapter 5 of Capital, volume 1. But no one has succeeded in disproving it. Bortkiewicz did not even try, nor does Rallo. [Emphasis in original.]

Shortly after I published this response, Romaniega, an associate of Rallo, rushed to his defense, alleging that I wasn’t telling the truth:

Es evidentemente falso que nadie haya mostrado que la demostración de Marx es incorrecta. Sin ir más lejos, en mi trabajo [Rom20] analizo expresamente la demostración de Marx y expongo los errores lógicos que contiene. Y es evidentemente falso que Rallo no lo haya hecho, ver [Ral22, Capítulo 1, Volumen II].

{It is evidently false that no one has shown that Marx’s demonstration is incorrect. Without going any further, in my work [Rom20] I expressly analyze Marx’s demonstration and expose the logical errors it contains. And it is evidently false that Rallo has not done so, see [Ral22, Chapter 1, Volume II].}

I strongly suspected that Romaneiga’s rebuttal was false; that neither he nor Rallo had exposed logical errors in Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration; that neither of them had even analyzed that demonstration; and that Romaniega was wrongly identifying chapter 1 of Capital with chapter 5. I am not the hotshot mathematician that he evidently is, but I do seem to recall having learned that 1 ≢ 5.

I therefore sent a message to Romaniega on June 8, in which I wrote:

I haven’t found the responses to Marx’s demonstration that you cite. Ral22, Capítulo 1, Volumen II is 260 pages long, and Rom20 is also not short. Could you please provide more specific citations, with page numbers? Please note that I’m asking specifically and only about Marx’s demonstration in chapter 5 of Capital, volume 1 … not his arguments in the 1st chapter. [Emphasis in original.]

Well—surprise, surprise—my strong suspicion was right. On August 19, Romaniega answered me and also posted a revised version of his critique of the temporal single-system interpretation of Marx’s value theory (TSSI). Neither Romaniega’s e-mail message nor his revised critique provides the more specific citations I requested!

Yet Romaniega failed to retract, much less apologize for, his false allegations and substance-free citations that I quoted above. His revised critique even repeats them verbatim. Like love and Marxian economics, libertarianism means never having to say you’re sorry.

In addition, the revised critique includes a discussion of Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration—for the first time (but omitting the fact that this is a belated addition; “we have always been at war with Eastasia”). So, does this added passage finally “expose the logical errors” in Marx’s demonstration?

Hardly. Romaniega not only fails to disprove Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration; he also concedes that the demonstration is correct! He writes that the proposition that “surplus value is not generated in circulation, but in production” is “demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67], as cited by Kliman. This demonstration is relatively trivial ….”

However—surprise, surprise—Romaniega now wants more than this to be demonstrated. He claims that “Chapter 5 ultimately resorts to the labor theory of value to conclude its demonstration” and that, consequently, it must also be demonstrated that “Marx’s theory of value [is] correct.”

This is complete nonsense. When Marx demonstrated that the amount of value in existence can only be redistributed, but not altered, in the exchange process, he did not appeal to the “labor theory of value” or to any other theory of the determination of commodities’ values. Romaniega purports to supply textual evidence for his contrary claim, but the passage he quotes is from the end of chapter 5. It comes after the completion of Marx’s demonstration that “surplus-value cannot be created by circulation,” and it has nothing to do with that demonstration.

The passage begins as follows: “We have shown that surplus-value cannot be created by circulation.” Marx’s use of the present perfect tense, “have shown,” makes clear that the demonstration has been completed. He then turns to a very different—indeed, opposite—issue: “can surplus-value possibly originate anywhere else than in circulation …?” (emphasis added). Marx’s answer to this latter question does refer to his theory of how commodities’ values are determined: “The commodity owner can, by his labour, create value, but not self-expanding [i.e., surplus] value.” But this reference to his value theory is quite clearly not about whether surplus-value can arise in the exchange process.

Furthermore, the issue that Rallo and I are addressing is whether Marx’s aggregate value-price equalities follow from his account of the transformation of commodity values into prices of production. In this context, the values of commodities are presupposed. They are the data on which the transformation is based, the basis on which the transformation takes place. No investigation can prove what it presupposes. So it makes no sense to demand from an investigation that presupposes Marx’s value theory that it also provide proof of that theory.

Thirdly, it is obvious that the issue of whether the exchange process can alter the total amount of value in existence is a separate question from the issue of how the magnitude of total value was determined (given only that this magnitude was determined prior to the exchange process, as Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration stipulates).

Although it is obvious that the two issues are separate, a formal explanation of exactly how and why they are separate may be helpful to some readers. So assume that

the possible pre-exchange magnitudes of total value are V1, V2, …, Vn.

If and only if

every post-exchange magnitude of total value must equal the corresponding pre-exchange magnitude,

then

the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence.

What proves the conclusion is the equality of the pre- and post-exchange magnitudes of total value. And since they must be equal in all cases, the conclusion has nothing to do with whether the actual pre-exchange magnitude of total value is V1 or V2 or … Vn.

I made what reduces to the same argument back in 2011 (p. 188, emphases in original):

Marx’s [chapter 5] demonstration does not depend upon the assumption that commodities exchange at their values. … In the above summation of his argument, I referred to commodities’ “worth,” not their “values.” … [W]e can assess the “worth” of commodities in terms of any structure of prices … and Marx’s conclusion still holds up. For instance, if I manage to buy a software program that has a monopoly price of $300 for only $250, I gain $50 in exchange while the seller loses $50. What matters is that the commodities’ prices––whatever they might be––are determined before the commodities enter into circulation. It is this premise, rather than the assumption that prices equal values, that underlies Marx’s argument.

Since he uses my terminology, referring to “what the commodities are ‘worth’” and “[w]hat they are ‘worth,’” Romaniega is clearly aware of this argument. He does not disprove it or even provide a counter-argument against it. He just ignores it, insisting, on the basis of a misrepresentation of the textual evidence, that “Chapter 5 ultimately resorts to the labor theory of value to conclude its demonstration.”

Romaniega’s claim that, “for the TSSI to be valid, Marx’s theory of value must be correct” is also wrong. The TSSI is purely and simply an exegetical interpretation of Marx’s value theory. As such, its success or failure depends solely on its ability to make Marx’s theory make sense (see my Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency, especially chapter 4). If Marx’s theory is incorrect, that is his problem, not the TSSI’s. If the TSSI makes his theory make sense, then, irrespective of whether the theory is or isn’t correct, the TSSI is a “valid” (i.e., correct) interpretation of it.

What Romaniega is doing here is moving the goalposts by shifting the burden of proof. He is the one who claimed to have “expose[d] the logical errors” in Marx’s demonstration that the process of exchange does not alter the total amount of value in existence. But finding himself unable to document the actual existence of his alleged exposé of logical errors, and finding himself unable to provide such an exposé now, Romaniega shifts the burden of proof onto the defenders of Marx’s theory. Suddenly, the issue is no longer whether Romaniega has proven (or can prove) that Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration contains logical errors; it is whether the defenders of Marx’s value theory can prove that the theory is correct. And the goalposts have moved, since, suddenly, more needs to be proven than the already-proven fact that Marx’s aggregate value-price equalities follow from his chapter 5 demonstration and his account of the value-price transformation. In addition, “Marx’s theory of value must be correct.”

This is the type of sophistical trickery up with which I will not put. What is at issue here is not whether Marx’s value theory is correct, but whether Romaniega has shown what he claims to have shown—“that Marx’s [chapter 5] demonstration is incorrect.” The preceding discussion makes clear that he has not.

Before moving on, I note that Romaniega has come close to demanding a logico-mathematical proof that Marx’s value theory is correct. But the theory is an empirical theory, and no empirical theory is proven “correct” by logical, mathematical, or other a priori means. The grounds for acceptance (non-rejection) of an empirical theory are a posteriori: it predicts and/or plausibly explains the relevant phenomena. As Marx himself noted long ago, “[t]he chatter about the need to prove the concept of value arises only from complete ignorance both of the subject under discussion and of the method of science.”

Do Supplies Equal Demands When Commodities Sell at Prices of Production?

When Romaniega rushed to Rallo’s defense, he also took issue with my statement that

prices of production exist as the long-run average (average over time) of the actual (market) prices that fluctuate around them. A commodity’s actual price rises above the price of production when demand exceeds supply, falls below it when supply exceeds demand, and equals it when supply and demand are in equilibrium.

Romaniega objected that “[n]o existe demostración de tal afirmación” (there is no demonstration of such a statement). In my June 8 message to him, I wrote that “I don’t know what this means. What sort of demonstration/proof do you want? What are its premises?”

Having now read Romaniega’s revised critique, which responds to my query by adding new material, it seems to me that what he wants demonstrated is the following proposition: a commodity’s equilibrium price is necessarily the price of production as defined by Marx. (The equilibrium price is the price at which the supply of and the demand for the commodity are in equilibrium.) In section 3.1, Romaniega writes that, “for supply and demand to be equal,” the prices must satisfy a certain supply-demand equilibrium equation (his Equation (3.1)), but the prices that satisfy that equation “are not necessarily Marx’s prices of production.”

One key problem here is that I didn’t claim that equilibrium prices are necessarily prices of production. I claimed the converse: prices of production are necessarily equilibrium prices (rather than disequilibrium prices).

And I am not alone. The statement of mine that Romaniega takes issue with simply reported what economic theory says about equilibrium in competitive industries in the long run (i.e., mutatis mutandis). It is what pre-Marx economic theory said, what Marx said, and what modern neoclassical theory says, even though they use different terminology from one another.

Since the terminological differences may be partly responsible for Romaniega’s confusion here, it may help to “map” the relevant terms and concepts of neoclassical theory onto those of Marx. Neoclassical theory says that, in a perfectly competitive industry in long-run equilibrium, the quantities of the good that are supplied and demanded are equal. Marx’s conceptions of a competitive industry and the long run are somewhat different from the neoclassical conceptions, but he says the same thing about supply and demand.

Neoclassical theory also says that, in a perfectly competitive industry in long-run equilibrium, the good’s (1) “equilibrium price” is just sufficient to cover (2) the “cost” to the producer—inclusive of (3) “normal profit.” (“Economic profit,” profit in excess of “normal profit,” has been eliminated.) Translated into Marx’s terminology, the numbered part of the same statement is: the good’s (1) “price of production” is just sufficient to cover (2) the “cost price” plus (3) “average profit.” And since the latter is in fact what Marx says, he and the neoclassicists are saying the same thing—about the relation between price of production, cost price, and average profit, and about the equality of supplies and demands in a competitive environment in the long run.

So, as I said, prices of production are necessarily equilibrium prices. And I need not demonstrate this, since it has already been demonstrated, time and again, to the satisfaction of at least the overwhelming majority of economists.

But wait, there’s more! Romaniega also seems to think that prices of production as defined by Marx are determined in a different manner elsewhere in his work, and he demands a demonstration that the two methods of determination arrive at the same result. Romaniega complains that “there is no demonstration” by TSSI authors that the prices that satisfy his supply-demand equilibrium condition, Equation (3.1), “oscillate around the prices of production” as defined in his Equation (2.3).

However, Equation (2.3) says nothing about how the magnitudes of prices of production are determined. It merely says that commodities’ prices of production are equal by definition to the commodities’ values plus some differences (positive, negative, or zero) between the prices of production and the values. Since Equation (2.3) leaves the magnitudes of these differences undetermined, it also leaves the magnitudes of the prices of production undetermined. If a price of production exceeds the associated value, the difference is positive, and vice versa. If a price of production is less than the associated value, the difference is negative, and vice versa.

So there are not two ways in which prices of production are determined, but only one. They are determined by processes that pre-Marx economic theory, Marx, and neoclassical theory more or less agree upon—except for the all-important issue of how the magnitude of average profit is determined, which is precisely what Marx’s account of the value-price transformation is intended to explain! If commodities sell at these prices of production, supplies will equal demands. As I have noted, this is agreed upon as well. And given the magnitudes of the prices of production determined in this manner, the magnitudes of the price-value differences can then be determined (i.e., calculated) by means of Equation (2.3).

And this is in fact how Romaniega determines (i.e., calculates) the magnitudes of the price-value differences in section 2 of his revised critique. The price-value differences are defined in his Equation (2.3) but their magnitudes are undetermined until he stipulates that all rates of profit are equal and, on that basis, writes down the “fully determine[d]” price-value differences of Equation (2.10). Since all prices are prices of production when all rates of profit are equal, Romaniega has, in effect, used the prices of production determined in the normal way—the way I explained above—to determine the magnitudes of the price-value differences.

The point here is that Romaniega’s own procedure makes clear that there is only one way in which prices of production are determined. There is no distinct “Marxian” theory regarding the determination of price-value differences that results in distinct “Marxian” prices of production that differ from the garden-variety cost-price-plus-average-profit prices that Marx called “prices of production” (and that other theories have called “normal prices” or “long-run, perfectly-competitive equilibrium prices”).

In sum, in the statement of mine that Romaniega challenged, I said that when commodities sell at their prices of production, supplies and demands are equal. That proposition has been demonstrated time and again. The process by which the prices of production are determined has also been demonstrated time and again. And there is no second, differently determined, set of “Marxian” prices of production. So nothing else needs to be demonstrated. My statement stands.

Editor’s note, Aug. 27: The original version of this article referred to Romaniega’s “Equation (2.9)” when it should have referred to “Equation (2.10).” The error has been corrected.

A response can be found here: https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/2025/11/09/response-to-klimans-comments-critique-of-klimans-academic-practices-and-theoretical-gaps/

ABSTRACT. This note responds to Andrew Kliman’s comments on my paper, “Mathematical Note on the TSSI as a Solution to Marx’s Transformation Problem.” I first document practices in his reply that violate scholarly standards (selective quotation that omits qualifying clauses and citations, quote manipulation that completes or alters quotations, and context stripping that changes the meaning of passages). The record also shows assertions that I conceded claims I explicitly contested, false statements about the timing and scope of revisions, and characterizations that ascribe to me positions I do not hold. These practices misrepresent my arguments and are incompatible with norms of academic debate and with a minimal commitment to truth-seeking and epistemic charity. I then clarify the substantive points. Treating a zero-sum exchange condition as sufficient to establish the TSSI premise g_t·x_{t+1} = 0 is a basic mathematical error, since the conclusion also requires identifying the benchmark price vector with the value vector, i.e., p^o = λ. Even if this identification is granted, a further proof is still needed to show that prices of production constitute long-run centers of gravitation for market prices when technical coefficients depend on prices. I conclude with precise questions that refocus the discussion on these testable claims and restore a minimal common ground where only the logical consistency of the arguments matters.

Having looked at Romaniega’s response, I’ve realized what his fundamental confusion is. He wants to reject Marx’s conclusion that total price equals total value, but he fails to understand the basis on which he needs to reject it.

Let g denote a gain or loss in exchange, p denote a commodity’s price, and v denote the commodity’s value. Marx’s theory says that

1. p = v + g

and, in Chap. 5 of vol. 1 of Capital, Marx demonstrates that

2. the (weighted) sum of the g terms equals 0.

Taken together, 1 and 2 imply that total price equals total value. Romaniega wants to reject that conclusion.

The problem is that he goes about it in the wrong way, by means of bad arguments that try to make 2 dependent on 1. But 2 is independent of 1, and it’s true.

Since 2 is true, the only way to reject the conclusion that total price equals total value is to reject 1. One needs to (a) deny that the commodity has a pre-exchange price or (b) assert that its pre-exchange price is unequal to v.

Claims (a) and (b) are worth considering, but they have NOTHING to do with Bortkiewicz’s critique of Marx’s value-price transformation account or Rallo’s revised version of Bortkiewicz’s critique. As I said above, “the issue that Rallo and I are addressing is whether Marx’s aggregate value-price equalities follow from his account of the transformation of commodity values into prices of production. In this context, the values of commodities are presupposed. They are the data on which the transformation is based, the basis on which the transformation takes place. No investigation can prove what it presupposes. So it makes no sense to demand from an investigation that presupposes Marx’s value theory that it also provide proof of that theory.”

I may or may not have more to say about Romaniega’s response. I doubt that he is discussing matters in good faith, and the response is low-quality overall, IMO. Just one example before I end this comment. In his response, he says,

“I wrote: ‘The first part would be demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67], as cited by Kliman. This demonstration is relatively trivial, although certain implicit assumptions are required, see [Ral22, Volume II, Chapter III, Section 2].’ He renders this as (see Figures 1a and 1b): ‘is demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67], as cited by Kliman. This demonstration is relatively trivial …,’ thereby (i) replacing ‘would be’ with ‘is’ and (ii) omitting the dependent clause that states the additional premises and supplies the citation.”

This allegation of wrongdoing is false. I did NOT replace “would be” with “is.” Romaniega’s version of what I wrote–“is demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67], as cited by Kliman. This demonstration is relatively trivial …”–MISQUOTES me. As one can verify by checking my article, above, what I actually wrote was “He writes that the proposition that ‘surplus value is not generated in circulation, but in production’ is ‘demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67], as cited by Kliman. This demonstration is relatively trivial ….'”

The reason I omitted the “would be” is that, in context, it needlessly complicates things and makes them hard to understand. The point is that Romaniega admits that there IS a demonstration in Chapter 5, and he implicitly admits that it IS true (because it IS “relatively trivial”). The reason I omitted “although certain implicit assumptions are required” is that this caveat is obvious–ALL demonstrations require assumptions–and because I myself call attention to the key assumption. In the article above, I quote my 2011 paper, in which I wrote, “the commodities’ prices––whatever they might be––are determined before the commodities enter into circulation. It is this premise, rather than the assumption that prices equal values, that underlies Marx’s argument.”

Romaneiga NOW objects to “certain implicit assumptions” in Marx’s Chap. 5 demonstration. He did not do so ORIGINALLY, but just stated that some are required. What he NOW objects to is “the assumption [sic] of zero-sum exchanges,” i.e., that what one party to an exchange gains is exactly offset by the other party’s loss. He suggests that Rallo disproved this. (I say “suggests” because that’s not actually what Romaniega’s text says, but it’s what I am guessing he means.)

But it’s just not true that Rallo disproved this. A good deal of the relevant section in Rallo’s book isn’t about exchanges at all, but about interest payments and the like. When he does deal with exchanges, he says NOTHING that challenges the obvious fact that what one party to an exchange gains is exactly offset by the other party’s loss.

In fact, Rallo says EXACTLY what Marx says in the chapter on commercial profit in Capital, vol. 3. The key passage in Rallo’s book is:

“Marx denies the possibility that surplus value arises from the mere circulation of commodity capital, since if commodities are systematically sold above their values, then they will also be systematically bought above them, and therefore capitalists will lose by buying what they gain by selling. This reasoning, however, omits the possibility that there exists a group of economic agents specialized in the distribution of commodities—let’s call them merchants or dealers—who systematically buy commodities below their value or systematically sell them above their value. … Let’s imagine that a producer has manufactured a television with a value equivalent to 100 hours of labor …. [T]he television manufacturer might be interested in selling the television to a specialized intermediary who offers to buy it … at a price offered below its value. … For example, suppose the television manufacturer is willing to sell their television for an amount of money equivalent to 95 hours of labor: in that case, it will suffice for the intermediary to sell it at its value (100 hours of labor) for them to obtain a surplus value of 5 hours of labor in the process of circulation of the goods.”

But this clearly does NOT CONTRADICT the idea that exchanges are zero-sum. It CONFIRMS it. The TV manufacturer sells a TV worth 100 to the wholesaler (“specialized intermediary”) for 95. Thus, the TV manufacturer loses 5 in the exchange (parting with 100 in the form of a TV but receiving 95 in the form of money) while the wholesaler gains 5 (parting with 95 in the form of money but receiving 100 in the form of a TV). This is the source of the wholesaler’s profit, but it’s a zero-sum exchange, since -5 + 5 = 0.

Then the wholesaler sells the TV to a retail buyer. This sale is NOT the source of the wholesaler’s profit. It is an exchange of equivalents–neither party gains or loses. The wholesaler parts with 100 in the form of a TV and receives 100 in the form of money; the retail buyer parts with 100 in the form of money and receives 100 in the form of a TV.

Marx wins again!

Romaniega’s statement that Marx’s demonstration, in chapter 5 of Capital, vol. 1, contains an “assumption of zero-sum exchanges” is also seriously wrong. That the exchanges are zero-sum is the main thing he is demonstrating. It’s not something he assumes.

In my article, above, I wrote, “And this is in fact how Romaniega determines (i.e., calculates) the magnitudes of the price-value differences in section 2 of his revised critique.”

In his response to me, he quotes this statement, italicizes the word “revised,” and then alleges:

“This is false. I added no material to the note regarding long-run average prices.”

But my statement is true. I cited section 2 of his revised critique and reported–accurately–how it determines the magnitudes of the price-value differences.

Romaniega is trying to make it seem as though I said that the material in question appears only in the revised version of his critique, not before then. But I didn’t say that or imply that. I was informing readers where they can find the material in question–in section 2 of the revised critique that I provided a link to earlier in the article. …

Or where they could find it by clicking the link. When one clicks the link now, it doesn’t bring up the version of the critique to which I referred, but a subsequent revision, written after my article was published. I apologize to readers that my article is no longer able to point them to the text I was referring to, but it is Romaniega, not I or this publication, that is responsible for the lack of a stable historical record.

Romaniega’s response falsely accuses me of “motte-and-bailey” argumentation.

(Here’s a decent definition of the term: “motte-and-bailey fallacies begin when someone presents a controversial, hard-to-defend point—the ‘bailey.’ Then, when another person challenges that position, the arguer replaces the weak point with a more defensible one, representing the motte.” https://answersingenesis.org/blogs/patricia-engler/2021/01/27/logical-fallacies-motte-bailey-arguments/?srsltid=AfmBOopVCJ2VpPZVIo9Up09DpCpxb8Ybrb-JM83K9obBMHy_vVyJFMYM )

Note that the motte-and-bailey fallacy occurs when one claim, about one issue, is defended by substituting a different (and weaker) claim about that same one issue. That is NOT what I have done. I have made different claims about different issues.

To make this crystal-clear, let’s look at Romaneiga’s full allegation. The italicized insertions, inside square brackets, are mine:

On p. 8 of his response, Romaniega writes,

“On the issue of the labor theory of value, which is fundamental to both the central TSSI premise and to Marxian economics in general (not just the TSSI interpretation), Kliman says the following. [Note the trick here, whereby all of the different issues are combined into one issue from the start: “the issue of the labor theory of value.” Romaniega doesn’t even make an argument that all of the different issues can be reduced to one. He just rules out the possibility that the issues may be different.] On the one hand, he claims that ‘Unlike rats, who flee a sinking ship, Álvaro Romaniega chose to board the Titanic—Juan Ramón Rallo’s “titanic . . . destr[uction] of Marx’s economic thought”—just as it was sinking.’ That is, the destruction of Marx’s economic thought is failing. [No, this restatement of what I said is inaccurate. I made a claim about one specific alleged destruction of Marx’s economic thought, Rallo’s, not “the destruction” as such.] Or more specifically, he states that [Kli25b], emphasis added:

‘According to the temporal single-system interpretation of Marx’s value theory (TSSI), his actual argument was radically different from the one they attribute to him. When we interpret his argument correctly, Marx’s conclusions follow logically from his premises; the alleged inconsistency simply vanishes.

‘Thus, there is nothing to correct. And thus, the aggregate value-price equalities are preserved.’

[That’s right–given the premises in Marx’s account of the transformation of values into prices of production, Marx’s conclusions, including the aggregate value-price equalities, follow logically. The amounts of value and surplus-value, determined in accordance with Marx’s value theory, are among these premises. Thus, the correctness or incorrectness of Marx’s theory regarding how they are determined (and defined, etc.) is not at issue here; in this context, they are just given. My claim here is about the logical validity of Marx’s derivation of the aggregate equalities, not about the soundness of his conclusion, and thus not about the correctness or incorrectness of Marx’s theory of how values and surplus-values are determined. Validity and soundness are different issues. One would think that a great logician in the tradition of Carnap would understand this.]

“Similarly, in [Kli25b], in the context of Bortkiewicz’s critique, Kliman considers the labor theory of value to be important, emphasis added: [Important to what, exactly? Might it be possible that “the labor theory of value” (a term that Marx didn’t use and a term and concept that I don’t accept) is important to some things, but not to other things like quantum mechanics, changing the oil in your car, the fact that the exchange process doesn’t augment value, cooking oatmeal, and the logical validity of Marx’s derivation of the aggregate value-price equalities?]

‘In his reply to me, Rallo refrains from commenting directly on this demolition of his attempted refutation of the law of value.’ [Yeah, this happens to be one of those instances in which the “labor theory of value” is important. It’s important in this instance because it’s what Rallo attempted to refute. That doesn’t make it important to quantum mechanics, etc.]

“But on the other hand, in the context of my critique that the central premise of the TSSI, gt · xt+1 = 0, needs the labor theory of value to be true, he says:

‘If Marx’s theory is incorrect, that is his problem, not the TSSI’s. If the TSSI makes his theory make sense, then, irrespective of whether the theory is or isn’t correct, the TSSI is a “valid” (i.e., correct) interpretation of it.’ [The actual context here (see my article above) is Romaniega’s incorrect claim that “for the TSSI to be valid, Marx’s theory of value must be correct.” This happens to be one of those instances in which the correctness of the “labor theory of value” isn’t important. It’s irrelevant in this instance, because the TSSI is (purely and simply) an exegetical interpretation of Marx’s theory. Whether an interpretation is or isn’t correct has nothing to do with whether the thing it is interpreting is or isn’t correct. For example, if someone says “the earth is flat,” and I interpret them as having asserted that the earth is flat, the fact that the earth isn’t flat does NOT make my interpretation incorrect.]

“This motte-and-bailey argumentation [Nope, no motte-and-bailey argumentation. As I’ve shown, I say different things about different issues.] is worth noting (at some points, there is no destruction of Marx’s thought and Marx’s value-price equalities follow logically from the premises, but at other points it is not relevant if Marx goes wrong with the labor theory of value).” [Quite right. Different issues, different claims. Vive la différence.]

1. I included a screenshot and exact paragraph quote of your exact wording and extensive quotations of your texts, so readers can see the full sentence in context. I am not misquoting, but showing what your composite “Frankenstein” phrase looks like when all the parts are put together.

2. On my supposed “admission” that Chap. 5 demonstrates the result. My original sentence reads: “The first part would be demonstrated in Chapter 5 … although certain implicit assumptions are required, see [Ral22 …],” and in the footnote I give more details on the assumptions and on the triviality of the result given those assumptions. You quote only the inner fragment “demonstrated in Chapter 5 … This demonstration is relatively trivial …” and then tell readers that I accept that there is a demonstration and that it is correct. Once the conditional “would be”, the dependent clause with the citation and the footnote are restored, it is evident that I did not concede such a thing. You are modifying the modality of my quote. I deny that there is a sound argument for the thesis of Chapter 5, as you need to include unproven premises (and not just p^o = λ) that are doing all the work and what remains is a triviality (a valid argument, as (p and q) → p is). Do you still maintain that I conceded the correctness of the Chapter 5 demonstration?

3. You also claim that I gave no specific references to critiques of Chapter 5 (“Neither Romaniega’s e-mail message nor his revised critique provides the more specific citations I requested!”). Yet the very clause you omit contains the reference “see [Ral22 …]”. Did I provide a reference to a critique of Chapter 5, yes or no?

4. You say you dropped “although certain implicit assumptions are required …” because all demonstrations require assumptions, and because you yourself highlight what you think is a key one. But our disagreement is precisely about which assumptions are being imported into Chap. 5 and whether they are innocuous. My point has always been that the assumptions are doing all the work. You cannot put what you think is the important assumption as my thought, because we have a disagreement; this should be obvious. You cannot modify the modality of an opponent’s quote; this is obvious again. Once you accept the existence of a pre-exchange price

p^oindependent of exchanges and fixed in production so that exchanges are zero-sum, we can measure losses and gains and the cancellation becomes a triviality. This has been my point always (see Footnote 3 of my original note and Footnote 8 of my response for more details). I do not deny that, once you have the offsets, there is a pairwise cancellation (if A gains 5, B loses 5); indeed, I give a formalization of how that idea would lead to the thesis of Chapter 5 once you have those premises as given. Yet you represent my position as if I denied that what one party to an exchange gains is exactly offset by the other party’s loss—which I explicitly do not. How can one understand my point and maintain that my objection is “new” or that my objection is the one you are citing here? I have serious doubts that you are (or want to) understand my point.And to restore a minimum of accuracy, it is Romaniega, not “Romaneiga”.

5. Based on all of this and previous interactions, I have serious doubts that you are understanding my critique. Maybe the mathematics/logic is the problem. For instance, you accuse me of confusion, based on your misreading of my position, while committing trivial mathematical errors like the one I expose in Example 3.1. You explicitly treat proving Δp·x = 0 as enough to imply g·x = 0, as if they were the same condition. Do you deny that you stated the claim that Δp·x = 0 is sufficient to obtain g·x = 0?

Romaniega’s statement (in his point 1) that “I am not misquoting” is a flat-out lie. In my article, above, I wrote that he said that a certain proposition is “demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67].” But in Romaniega’s version, I wrote that he said that the proposition “is demonstrated in Chapter 5 of [Mar67].” That is an obvious misquotation. When I reported his statement–the stuff inside the quotation marks–I did not include the word “is.” But in his version, I did include it.

This is important because Romaniega is the new Bill Clinton. He’s making a federal case of what the meaning of the word “is” is. But even if it weren’t important, his version would still be a misquotation and his denial that it is a misquotation would still be a flat-out lie.

But it’s not his biggest lie. I’ll be exposing a much bigger one, maybe in a new article.

You misquote me because:

1) You modify the modality of my quote (from a conditional to an affirmative assertion). You use this to say that I concede that the proof of Chapter 5 is correct. I did not concede such a thing.

2) You truncate the part where I add a critique of Chapter 5. Then you claim that “Neither Romaniega’s e-mail message nor his revised critique provides the more specific citations [critiques of Chapter 5] I requested!”

Question: Did you alter the modality of my quote? Did you truncate the part where I was giving a specific reference and then claim I gave none? Yes or no.

I have included screenshots of your exact quote and I refer to them, so it is difficult to maintain that I am misquoting you.

“I have included screenshots of your exact quote and I refer to them, so it is difficult to maintain that I am misquoting you.”

Not at all difficult, because it’s the truth. You included and referred to screenshots that confirm that you misquoted me.

Romaniega’s point 3 is another flat-out lie. As I noted in the article above, what I wrote to him was “I haven’t found the responses to Marx’s demonstration that you cite. Ral22, Capítulo 1, Volumen II is 260 pages long, and Rom20 is also not short. Could you please provide more specific citations, with page numbers?”

He claims in point 3 that “the very clause you omit contains the reference.” The full sentence–in the latest, Sept. 30 revised version of his critique–continues to be “Y es evidentemente falso que Rallo no lo haya hecho, ver [Ral22, Cap´ıtulo 1, Volumen II].” THIS IS NOT A MORE SPECIFIC REFERENCE WITH PAGE NUMBERS. It continues to be a reference to something 260 pages long. ROMANIEGA’S SENTENCE STILL DOES NOT PROVIDE THE MORE SPECIFIC REFERENCE WITH PAGE NUMBERS THAT I REQUESTED.

https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/valentine-for-Romaniega.jpg

I do not have time to reply to all the output (my note still stands and I invite anyone to check), but let us see one particular example. You are recasting the disagreement by cherry-picking, quoting selectively, and omitting the important parts to make an argument. Again.

In my note, I quoted your paragraph:

My “This is false. I added no material …” is clearly directed at the first, principal claim: that my revised critique “responds to [your] query by adding new material.” I denied your historical claim that I changed the note by adding new material in response to your June 8 query on prices of production and equilibrium prices.

In your new comment, however, you ignore the “which responds to my query by adding new material” part and tell readers that I am wrongly denying only the tail end (“And this is in fact how Romaniega determines … in section 2 of his revised critique”). That is not what I wrote, and not what I denied. You are truncating my quote, and it is mala praxis. How can one possibly think it reasonable to remove your own claim that I added new material when my response explicitly says “I added no material” and is clearly targeting that? This has been a constant pattern in this debate.

So the concrete question is: comparing the May 20 and August 19 versions of my note, can you identify any “new material” on long-run average prices, added after your query, that was not already there and that actually “responds to [your] query”?

Everything I wrote is accurate.

First, I wrote, “Having now read Romaniega’s revised critique, which responds to my query by adding new material, it seems to me that what he wants demonstrated is the following proposition: a commodity’s equilibrium price is necessarily the price of production as defined by Marx.” Completely accurate: I wrote this after reading the revised critique; the revised critique responds to my query by adding new material; and what I guessed that Romaniega wanted demonstrated is what I said here that I guessed.

Then, nine paragraphs later–and Romaniega has the gall to complain about cherry-picking!–I wrote, “And this is in fact how Romaniega determines (i.e., calculates) the magnitudes of the price-value differences in section 2 of his revised critique.” This is also completely accurate.

After piecing these things together and adding italics, Romaniega charges that what I said is false because “I added no material to the note regarding long-run average prices” (emphasis added). But I never said that he did. I said that the revised critique responds to my query by adding new material, which it does, and that Romaniega determines (i.e., calculates) the magnitudes of the price-value differences in section 2 of his revised critique, which he does.

If Romaniega published in a proper manner, indicating each specific change in his text, exactly what has been changed, and when, he wouldn’t be having this problem. But since he doesn’t publish in a proper manner, I have to cite the current version that readers can access, and inform them that the text was been changed in light of my query. And it’s not my job to scrutinize every word and symbol to determine whether what is there now was also there before. It’s his job as author and publisher.

You say, emphasis added:

That is, your query is about the oscillation of prices around prices of production. I say there is no proof of that. You made a query about the proof and say that I responded by adding new material. But I added no material regarding equilibrium prices. I did not answer that query (which is about equilibrium prices) by adding new material. My question is the same: comparing the May 20 and August 19 versions of my note, can you identify any “new material” on long-run average prices, added after your query, that was not already there and that actually “responds to [your] query”?

You also say that “I have to cite the current version that readers can access,”. This is false. All the versions are available and date-stamped, so you CAN CITE whichever you want.

When I use the link that Romaniega sent me on August 19,

https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/2025/04/28/nota-matematica-sobre-la-tssi-como-solucion-al-problema-de-la-transformacion-de-marx/

what I get is one version (in Spanish and English) only, dated September 30, 2025. Not the version published on or about August 19, and not a version that apparently existed on April 28.

However, the page indicates–twice, at the top and at the bottom–that this September 30 document was published on April 28!!! (See screenshot: https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Romaniega-time-traveller.jpg )

The references section of the document includes no entries on prior versions. Nor does the document provide links to prior versions. as far as I can see, the page that the document is on also fails to include these entries and links.

Because of all this, I have no citation information and no links other than https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/2025/04/28/nota-matematica-sobre-la-tssi-como-solucion-al-problema-de-la-transformacion-de-marx/ . So as I said, “I have to cite the current version that readers can access.”

I kindly request that Romaniega adhere to proper publishing standards: indicate each specific change in his text, exactly what has been changed, and when.

Romaniega keeps repeating that what he says is clear and has been explained. But the most basic things are still unclear to me.

For example, he writes, “the oscillation of prices around prices of production. I say there is no proof of that.”

However, (1) I went into this, at length, in my article above, explaining that it has been demonstrated time and again that prices of production are equilibrium prices; and (2) Romaniega’s response document says on p. 15 that “I am not denying ‘what economic theory says about equilibrium in competitive industries in the long run'”.

So it’s still completely unclear to me why he says that there’s no proof of what I wrote: “prices of production exist as the long-run average (average over time) of the actual (market) prices that fluctuate around them. A commodity’s actual price rises above the price of production when demand exceeds supply, falls below it when supply exceeds demand, and equals it when supply and demand are in equilibrium.”

A simple question.

In note 8 of his response to me Romaniega writes,

“From ‘On Capitalism’s Historical Specificity and Price Determination’ by Kliman,

‘The crucial and necessary premise underlying his demonstration is that commodities have determinate prices, as well as values, before they enter into the market.’

“No valid argument for this claim is provided.”

Which claim, mine or Marx’s (which I clearly identify here as a premise of his chapter 5 demonstration)?

On p. 10 of his response to me, Romaniega charges that I “never mention[] my central point that two steps are needed to prove the condition gt · xt+1 = 0 ….”

This is outrageous. I not only mentioned this, but, in the article above, I devoted several paragraphs to refuting it. Here again is part of what I said:

“Thirdly, it is obvious that the issue of whether the exchange process can alter the total amount of value in existence is a separate question from the issue of how the magnitude of total value was determined (given only that this magnitude was determined prior to the exchange process, as Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration stipulates).

“Although it is obvious that the two issues are separate, a formal explanation of exactly how and why they are separate may be helpful to some readers. So assume that

the possible pre-exchange magnitudes of total value are V1, V2, …, Vn.

“If and only if

every post-exchange magnitude of total value must equal the corresponding pre-exchange magnitude,

then

the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence.

“What proves the conclusion is the equality of the pre- and post-exchange magnitudes of total value. And since they must be equal in all cases, the conclusion has nothing to do with whether the actual pre-exchange magnitude of total value is V1 or V2 or … Vn.”

As far as I can see, Romaniega has not responded directly to this argument.

He wants to deny that actual prices of production equal the prices of production determined in accordance with Marx’s theory. What he needs to do, as I noted in my comment of November 12, 2025 at 8:18 pm, is either deny that commodities have pre-exchange prices or assert that their pre-exchange prices are unequal to their values–and stop pretending that the proposition that the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence requires “proof” of the “labor theory of value” as a distinct “step.”

Answer: in Footnote 8 of my note it is clearly explained which premises you need and how one is essentially assuming what one needs to prove, up to a trivial cancellation. This has been my point all the time.

But, again, I have serious doubts that you are understanding my critique. Maybe the mathematics/logic is the problem. For instance, you accuse me of confusion, based on your misreading of my position, while committing trivial mathematical errors like the one I expose in Example 3.1. You explicitly treat proving Δp·x = 0 as enough to imply g·x = 0, as if they were the same condition. Question: Do you deny that you stated the claim that Δp·x = 0 is sufficient to obtain g·x = 0?

I initially thought that Romaniega’s Δp referred to price – value, in which case Δp and g are identical. My comment to him in a private email message–not in anything published (until he published it without my permission)–was based on that. I later realized that he meant something different by Δp. So what? What’s the point?

I have a simple yes-or-no question for him. I kindly request that he answer yes or no, not give us his usual song and dance.

Is the following true?:

If and only if

every post-exchange magnitude of total value must equal the corresponding pre-exchange magnitude,

then

the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence.

Yes or no?

The sound of Romaniega silence.

Good that you recognize that you criticized my note in the emails before understanding what it says (what you missed is essential). And this has already been answered, yes, and it is a yes because you are essentially assuming what you need to prove, that is, a triviality; i.e., the answer to “is it true that p iff p?” is clearly a yes but proves nothing of interest. This has been my point for months. In my note I explain all of this in detail. One just needs to read.

Antonio, I have been explaining all of this from the beginning, and I explained this to you on Twitter months ago. And you personally know that I have plenty of things to do before wasting my time here in this unproductive exchange. It is not honest to imply that the silence is due to anything other than that.

https://x.com/alvaro_ARS_/status/1960773861382775037

I asked whether it’s true that “if and only if every post-exchange magnitude of total value must equal the corresponding pre-exchange magnitude, then the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence.”

Romaniega has now (December 4, 2025 at 8:40 am) explicitly said “yes,” it is true. This admission–that the exchange process is zero-sum–completely destroys his whole critique of the TSSI.

His fundamental point–i.e., fundamental mistake–is his claim (in his opening comment of November 11, 2025 at 9:06 am, above) that “treating a zero-sum exchange condition as sufficient to establish the TSSI premise g_t·x_{t+1} = 0 is a basic mathematical error, since the conclusion also requires identifying the benchmark price vector with the value vector, i.e., p^o = λ.”

This is false, since, in the paper he criticizes (“A temporal single-system interpretation of Marx’s value theory”), the vector g is DEFINED as “a gain (or loss) of some amount of value … in exchange” (p. 36). Hence, the total of the g terms (g_t·x_{t+1}) MUST equal 0 if the exchange process is zero-sum. And Romaniega now explicitly admits that it is true that the exchange process is zero-sum. Hence, the total of the g terms MUST equal 0, whether or not “the benchmark price vector” equals “the value vector.” Q.E.D.

Furthermore, the equality or inequality of “the benchmark price vector” and “the value vector” has to do with whether Marx’s value theory is true. But it has nothing to do with the paper in question. In the first place, we say explicitly that “Our focus is solely interpretive” (p. 34) and that “We shall … refrain from evaluating Marx’s value theory” (p. 35). Secondly, we specify that the interpretive question we address is “must Marx’s own value theory be judged internally inconsistent …?” (pp. 34-35). Because the paper is solely interpretive, and because the interpretive question pertains to internal (in)consistency only, not truth, Romaniega’s whole critique is the critique of a straw man he has invented.

Romaniega (December 4, 2025 at 8:40 am) says that I criticized his note (in an unpublished email message) before understanding what it says, and that what I missed is “essential.”

Yes, I was reading charitably, too charitably. I wrongly assumed that he wasn’t falsifying the stated meaning of g.

I agree that his falsification–his replacement of stated meaning of g with his own, different meaning–is essential. It’s an essential falsification.

Let me point out that Romaniega has not responded–either in his response to me or in the comments here–to my disproof of one of his most crucial claims.

The claim is contained in the August 19 revised version of his critique. He wrote there that,

“as we have seen in the quote from [Mar67], Chapter 5 [of volume 1 of Capital] ultimately resorts to the labor theory of value to conclude its demonstration. Therefore, for the TSSI to be valid, Marx’s theory of value must be correct.”

In my article, above, I disproved Romaniega’s claim that Chapter 5 “resorts to the labor theory of value to conclude its demonstration”:

“This is complete nonsense. When Marx demonstrated that the amount of value in existence can only be redistributed, but not altered, in the exchange process, he did not appeal to the ‘labor theory of value’ or to any other theory of the determination of commodities’ values. Romaniega purports to supply textual evidence for his contrary claim, but the passage he quotes is from the end of chapter 5. It comes after the completion of Marx’s demonstration that ‘surplus-value cannot be created by circulation,’ and it has nothing to do with that demonstration.

“The passage begins as follows: ‘We have shown that surplus-value cannot be created by circulation.’ Marx’s use of the present perfect tense, ‘have shown,’ makes clear that the demonstration has been completed. He then turns to a very different—indeed, opposite—issue: ‘can surplus-value possibly originate anywhere else than in circulation …?’ (emphasis added). Marx’s answer to this latter question does refer to his theory of how commodities’ values are determined: ‘The commodity owner can, by his labour, create value, but not self-expanding [i.e., surplus] value.’ But this reference to his value theory is quite clearly not about whether surplus-value can arise in the exchange process.”

Romaniega’s Big Lie

Because exact formatting is important in this context, I have turned this comment of mine into a PDF document, accessible by clicking the following link:

https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Romaniegas-Big-Lie.pdf

It is really simple, but you still refuse to understand. One could wonder why. It is a constant straw man instead of a steel man, which would be proper academic style. I can understand that sometimes there are different interpretations, but the fact that you insist after it has been clarified and even attack harder is improper by any minimal academic standard. You said, emphasis added:

Also, from the same post:

I replied:

What am I criticizing? The fact that the demonstration of the aggregate value–price equality (equivalently, that total price equals total value) is presented as if it had not been successfully criticized, or as if no (unrefuted) argument had been given to overturn the aggregate equalities, a demonstration which would be concluded in Chapter 5.

What do you need to refute/overturn this equality? It is sufficient to refute the labour theory of value.

What is [Rom20], as it appears in my note? It is a work titled: “Theoretical analysis of the proofs of the labour theory of value. Critique of Karl Marx and Ernest Mandel”.

Anyone with a minimal aim to understand, and without wanting to muddy the waters as much as possible to cover other issues, can see this. If this is the “big lie”, it is clear that my note stands and reflects the practices of its opponents.

In case anyone is inclined to think that Romaniega has a point here, I suggest that you ignore his cherry picking and rearrangement of quotes and simply read the 2nd and 3rd paragraphs of the screenshot at the top of p. 2 here: https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Romaniegas-Big-Lie.pdf . Romaniega very clearly responded to my statement, that no one has successfully disproven Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration, by falsely alleging that he had exposed the logical errors in that demonstration.

You keep shifting the discussion, ignoring the obvious, and avoiding the central questions. I do not have time to go through everything in detail, and it seems you have far more time to devote to this, including to things that do not really belong in an academic exchange. In particular, this image you have posted is improper by any reasonable standard; I do not have the time and do not wish to be involved in this situation:

https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/valentine-for-Romaniega.jpg

I am going to pick some concrete examples:

1) You modify the modality of my quote (from a conditional to an affirmative assertion). You use this to say that I concede that the proof of Chapter 5 is correct. I did not concede such a thing. I have explained this several times, but you insist.

2) You truncate the part where I add a critique of Chapter 5. Then you claim that “Neither Romaniega’s e-mail message nor his revised critique provides the more specific citations [critiques of Chapter 5] I requested!” But I provided a reference that is a specific critique titled “surplus value is not only generated in the sphere of production”.

3) You claimed that: “[…] by disproving Marx’s demonstration in chapter 5 of Capital, volume 1. But no one has succeeded in disproving it.[4] Bortkiewicz did not even try, nor does Rallo.” But this is false, even for the narrow interpretation of the part of the proof that surplus is not generated in circulation. As I explained in the truncated quote, Rallo does critique Chapter 5: Rallo 2022, Volume II, Chapter 3, Section 2.

4) In my response note I provide links to all the versions (I follow the same style as in academia in mathematics for preprints like arXiv; it is also standard in economics preprints, as anyone doing academic research knows, e.g. SSRN). It is standard: one just needs to change the number in the URL to get to the different versions. I can understand that someone is not familiar with this (my fault for not realizing and not being more explicit), but then they should ask and not claim it is not possible to access the previous versions, especially when they are explicitly published in my response note.

But again, this is off the rails and I will not waste my time here:

https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/valentine-for-Romaniega.jpg

I have dealt fully with Romaniega’s point 1. It reduces to the issue of whether the following is true: If and only if every post-exchange magnitude of total value must equal the corresponding pre-exchange magnitude, then the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence. He keeps avoiding my request that he give a simple yes or no answer as to whether this is true.

In re point 2, the issue isn’t whether “surplus value is … only generated in the sphere of production.” I have made that clear repeatedly. The issue is whether the exchange process can alter the total amount of value that existed before it. That’s what Marx’s chapter 5 demonstration is about.

In re point 3, I documented, in my comment of November 16, 2025 at 8:55 pm, that I made the following request: “Could you please provide more specific citations, with page numbers?” However, “[t]he full sentence–in the latest, Sept. 30 revised version of his critique–continues to be “Y es evidentemente falso que Rallo no lo haya hecho, ver [Ral22, Cap´ıtulo 1, Volumen II].” THIS IS NOT THE MORE SPECIFIC REFERENCE WITH PAGE NUMBERS THAT I REQUESTED.

In re point 4, Romaniega claims that “one just needs to change the number in the URL to get to the different versions. But the URL is https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/2025/04/28/nota-matematica-sobre-la-tssi-como-solucion-al-problema-de-la-transformacion-de-marx/ . What exactly are people supposed to change 2025/04/28 to?

Romaniega apparently believes that he shouldn’t eat shit and die. He’s entitled to his opinion.

The Definitive Solution: From Temporal Sequence to Fractal Geometry

Dear Professor Kliman, I am pleased to address you with my deepest respect and admiration to inform you of a revolutionary theoretical advance I have developed that definitively resolves the transformation problem, settling a century-old debate, but within the realm of pure mathematics and overcoming the plausible, entirely respectable, and understandable limitations of the Temporal Single-System Interpretation (TSSI).

TSSI was historic: it saved Marx from logical incoherence by reintroducing time. However, my T-Transformation absorbs its approach and definitively surpasses it, demonstrating that Value is not only a sequential magnitude, but a Fractal Object.

I have resolved the transformation problem by elevating it to a new scientific dimension: Mathematical Overcoming (From the Path to the Attractor): While TSSI calculates the temporal sequence step by step, T-Transformation reveals the final structure. I have formally demonstrated that its temporal sequence is, in fact, an iteration that converges toward a Fractal Attractor (Λ). The TSSI explains the genesis; my model defines the resulting geometry.

Ontological Resolution (Shadow Theory): The discrepancy between values and prices is not an error to be minimized; it is a dimensional projection. Value is an infinite-dimensional object (the fractal); price is its flat shadow projected by competition (Rn). The distortion is geometrically necessary, validating Marx’s intuition about form and substance through an advanced topology.

Empirical Revolution (Falsifiability): Unlike the algebraic nature of the TSSI, the T Transformation introduces one or more calibratable parameters. I have applied this to World Input-Output Tables (WITTs), enabling the precise measurement and mapping of value transfer in modern imperialism. They won the logical battle of the 20th century. The T-transform opens the door to 21st-century empirical science. The problem is no longer one of accounting; it has been solved as a problem of geometric optimization.

I would greatly appreciate the opportunity to collaborate on this joint, formal, and far-reaching scientific project. In short, I recommend that you stop debating with second-rate academics and pseudo-rationalists like Romaniega, who are only seeking academic gain by interacting with such a prominent intellectual figure as yourself.

Sincerely,

Ángel Barroso

Hi Ángel,

I wish you success in this work, but there’s no way I could help. I know what fractals are in a general way, but I’ve never studied them and it would be very hard for me–especially at my age–both to study them and to think through how they are related to the theoretical economic issues. Plus, there are other (personal) problems weighing me down at the moment.

I appreciate what you say about Romaniega.

I will not waste time reiterating points that have already been established. My arguments in the note clearly stand (see Sections 3 and 4 there), and the current tone of the debate has fallen below minimal academic standards. I prefer to allocate my time to publishing in journals and presenting at international conferences rather than engaging in exchanges that lack epistemic charity (instead of apologising, you reaffirm your “eat shit and die” or fractal hallucinations). To illustrate why further discussion is unproductive, I will address one specific intentional or unintentional error in your response that should have been resolved in a single iteration in any reasonable academic debate.

You wrote:

When I wrote that “one just needs to change the number in the URL,” I was referring to the file name of the PDF in the uploads folder, not the date segment (“2025/04/28”) of the blog post. This should be evident if one reads what I wrote. The date remains constant, but the file sequence increments (e.g., nota_tssi-2, nota_tssi-3, nota_tssi-4). By changing that number, one accesses the different versions.

For instance, this is version 4:

https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/nota_tssi-4.pdf

These versioned files are explicitly linked in my response note. So the supposed mystery about what people are meant to change in the URL can only arise, assuming there is no bad faith, from not having read what I actually wrote. In any case, this is not rocket science, and your own page “Marxist-Humanist Initiative” is hosted following the same structure. Several weeks have gone by and you have not been able to understand or acknowledge this simple fact: that all the versions have always been available. On the contrary, you stated recently that “Nor does the document provide links to prior versions,” when my response note does. All in all, this implies, again, that this is a waste of time.

I have never denied that all versions are “available” in your quite misleading sense. I have said, correctly, that they cannot be accessed by clicking the link to the URL of the page you cite–e.g., in your opening comment of November 11, 2025 at 9:06 am: “A response can be found here: https://alvaroromaniega.wordpress.com/2025/11/09/response-to-klimans-comments-critique-of-klimans-academic-practices-and-theoretical-gaps/ –or any other link on the page.

More importantly, I have repeatedly and rightly condemned your improper publishing method, which unethically makes it hard to find out what the historical record is and hard to piece it together. As I said in 2 comments of Nov. 16:

“If Romaniega published in a proper manner, indicating each specific change in his text, exactly what has been changed, and when, he wouldn’t be having this problem. But since he doesn’t publish in a proper manner, I have to cite the current version that readers can access, and inform them that the text was been changed in light of my query. And it’s not my job to scrutinize every word and symbol to determine whether what is there now was also there before. It’s his job as author and publisher.”

“I kindly request that Romaniega adhere to proper publishing standards: indicate each specific change in his text, exactly what has been changed, and when.”

You have not done this. You wrongly think that you have better things to do, like falsify the stated meaning of g and falsely deny that you alleged–falsely–that you had “expose[d] the logical errors” in Marx’s demonstration in chap. 5 of vol. 1 of Capital.