Karl Marx Systematically Exploited by Ben Burgis

Marx’s Exploitation Theory vs. G. A. Cohen’s “Plain Argument”

by Andrew Kliman

Section 1: Theoretical Appropriation to Make Marx Safe for Social Democracy

The term cultural appropriation refers to the exploitation of one group’s culture by members of a different, more dominant culture. The appropriators lay hold of particular bits of another culture, detach them from their overall context, and rework them to suit their own purposes. Criticism of cultural appropriation has increased substantially in recent years.

Yet there is still almost no criticism of an analogous exploitative process that operates in the intellectual realm, which we can call theoretical appropriation. It seems that many people find it completely acceptable, while others engage in it as a savvy career decision without regard to its ethical implications. Yet theoretical appropriation differs from cultural appropriation only in that the exploiters and the exploited are intellectual rather than cultural groups, and that the bits of stuff that the appropriators lay hold of, detach from their overall context, and rework to suit their own purposes are bits of theory rather than bits of culture.

Because of the abiding cachet surrounding Karl Marx’s name and legacy, his work has long been the victim of theoretical appropriation. Nowadays, the most typical aim of those who exploit his work in this manner––and who of course call the result “Marxism”––is to make Marx safe for social democracy.

What social democracy promises, above all, is a more “just” distribution of income. Often, though not always, this political promise is accompanied by an ideological promise that a “just” distribution of income can be achieved within capitalism––that is, achieved even as workers continue to lack means of production that would enable them to produce on their own, so that they must either starve or work for, and under the direction of, others.

Accordingly, the bit of Marx’s work that is most commonly targeted for appropriation and refashioning––to turn it into a theory about “unjust” income distribution––is his exploitation theory of profit, the theory that the extraction of surplus labor from workers is the sole source of capitalists’ profit (and other property income such as interest, dividends, and rent).

The theory in its original form isn’t safe for social democracy. That is partly because it says that the exploitation occurs in the capitalist process of production, rather than in the realm of income distribution. And it is partly because the theory in its original form says that the sole source of capitalists’ property income is this same exploitation in production, not an “unjust” income-distribution policy that social democracy can change while leaving capitalist relations of production untouched.

The appropriators therefore have to turn Marx’s exploitation theory of profit into a theory of exploitation, and they have to make capitalist exploitation a matter of income distribution rather than a matter of capitalist production relations. To do so, they appropriate the bare idea that capitalists exploit workers, detach it from Marx’s original exploitation theory and the rest of his work, substitute one or another theory that makes exploitation a matter of “unjust” income distribution, and––of course––attach the name Marx to the result.

Over the years, there have been a great many efforts to exploit Marx in this way. This article is just about the most recent version of that project, Ben Burgis’ 2019 piece, “Marx’s Theory of Exploitation,” together with his 2022 piece, “Karl Marx Was Right: Workers Are Systematically Exploited Under Capitalism.”[1] Since G. A. Cohen’s 1979 essay, “The Labour Theory of Value and the Concept of Exploitation,” is the foundation underlying Burgis’ recent writings, the article examines it in detail as well.[2] What I want to show is that Cohen’s and Burgis’ revisions of Marx’s exploitation theory do not actually replicate the substance of the original theory by other means and, equally importantly, that they are unsuccessful on their own terms, owing to errors of reasoning and fact. Between Cohen’s errors and Burgis’ additional errors, there are a lot of errors to deal with, and it always takes much more space to expose and correct an error than to make one, so this article is unfortunately rather long.

Plan of Subsequent Sections

Section 2 will discuss the meaning of the term exploitation, focusing especially on how “exploitation of labor by capital” or “exploitation of workers by capitalists” have been explicitly or implicitly defined in the works of Marx and other economists and social scientists, and in Cohen’s essay. This discussion is important to the rest of the paper, since I will later show that Cohen’s alternative to Marx’s exploitation theory, which he called the “Plain Argument,” fails to demonstrate that capitalists exploit workers, and I will employ Cohen’s own definition to show this. I will also argue that Burgis’ lack of attention to Cohen’s definition is among the reasons he fails to recognize that the “Plain Argument” does not succeed, and that Burgis’ defenses of the “Plain Argument” do not grapple with the issue of exploitation as defined by Cohen.

In Section 3, I discuss the fact that Burgis 2022 repeatedly presents capitalist exploitation of workers as a matter of capitalists controlling “part of the product.” This is either a new formulation or at least a highlighting of an element of Burgis’ thinking that he had not emphasized before. I argue that this conception of capitalist exploitation is in conflict both with the facts and with Marx’s theory, and that it is unable to capture how the dynamics of class struggle––struggles over the length of the workday (or workweek) and over workers’ wages and benefits––affect the magnitude and degree of exploitation.

The next three sections focus on the “Plain Argument.” In Section 4, I discuss Cohen’s goal, strategy, and intended audience. I also discuss his alleged proof that Marx’s exploitation theory contradicts his value theory and is therefore untenable. Cohen argued that, if anything justifies the charge that capitalists exploit workers, it is his own “Plain Argument,” not the theory of Marx’s that he had demolished. I show, however, that Cohen’s proof fails because he conflated distinct concepts (creation and determination of value). Section 5 then shows that the “Plain Argument” fails to prove that capitalist exploit workers because the argumentation is logically invalid; it also provides ethical and political reasons one should care about logical validity.

Burgis holds fast to the “Plain Argument” despite my demonstration. As I discuss in Section 6, he holds fast to it despite the fact that Cohen himself declined to endorse it. I argue that Burgis continues to embrace the “Plain Argument” because he has not adequately understood it. I also argue that what he has written in defense of the “Plain Argument” does not grapple with the essential question of whether the capital-labor relation is exploitative in Cohen’s sense.

Section 7 turns to Marx’s exploitation theory. I argue that it is not plagued by the problems that make the “Plain Argument” unsuccessful, and I explain why this is the case. I then show that Marx was adamantly opposed to the view put forward by Burgis (and Cohen) that exploitation is morally wrong because it results in an unjust distribution of income. His own view was that present-day income distribution is just, given the capitalist mode of production, and that a “higher” form of distributive justice is possible by only by overcoming capitalism and replacing it with socialism.

Section 2: What is Exploitation?

Exploitation occurs when someone or something (a material resource, an opportunity, etc.) is used or taken advantage of. Economists and other social scientists are chiefly concerned with the exploitation of people and classes, who are generally considered exploited if they are required, by force or circumstances, to contribute more to some process than they receive in return.

The disproportion between receipt and contribution is crucial to the meaning of exploitation. It highlights the distinctive character of exploitation, that which makes it different from (though not unrelated to) domination, oppression, and other expressions of unequal power. The main economic and social-science theories that invoke the concept of exploitation all have to do with the disproportion between receipt and contribution.

Marx’s exploitation theory of profit says that, during one part of the time they work, the labor of workers in capitalist production adds to products an amount of new value equal to the workers’ wages and benefits. But they are made to work longer than that. During the rest of the time they work, their labor adds additional new value (surplus-value), for which they are paid no equivalent. Hence, the workers are exploited: they contribute one amount of new value, by working, but receive as pay only a smaller amount of value. The additional labor they perform, for which they are paid no equivalent (surplus labor), is the exclusive source of the difference between the new value created and the amount of value that the workers are paid or, in other words, the exclusive source of the surplus-value or profit.

Neoclassical economics has been the dominant school of bourgeois economics for almost a century and a half. It has a very different conception of exploitation. It reasons in terms of owners of productive inputs or resources––such as labor, land, machinery, and raw materials––who sell or rent them to business firms that employ the inputs in production. A longstanding neoclassical theory says that the owner of an input is exploited if the payment s/he receives for supplying the input is less than what the theory regards as the input’s contribution to production––the value of its marginal product. If the payment exceeds the value of the input’s marginal product, the supplier is an exploiter. (The input’s marginal product is the additional physical output that results from the employment of an additional unit of the input. The value of this extra output is the price it would command if the economy were perfectly competitive and in equilibrium.) In this theory, exploitation of firms by suppliers of labor (or of any other input) is just as possible as exploitation of suppliers of labor (or of any other input) by firms. Although the neoclassical conception of exploitation is much different than Marx’s in many respects, it too involves the relation between contribution (supply of inputs) and receipt (payments received from sale or rental of inputs).

Two decades ago, Aage B. Sørensen, a Danish-American sociologist, proposed a theory of class exploitation based on the neoclassical economic theory. He argued that groups that are able to exact what neoclassical economists call “rent”––payments for their inputs that exceed the minimum payment needed to make the inputs available––are exploiting classes. They are better off, and those who pay them are worse off, than they would be in the absence of rent. Indeed, the purpose of “rent-seeking behavior” (e.g., lobbying the government for protection from competition) is to enhance one’s well-being at others’ expense. Here again exploitation is a matter of the exploited receiving less than they contribute (because the exploiters receive more than they contribute).

For all its faults, Cohen’s “Plain Argument” that capitalists exploit workers does at least respect the common meaning of the term “exploitation.” In contrast to Burgis, Cohen did not gloss over the distinction between exploitation and “unjust” property rights, capitalists’ ownership/control of the product, their domination of workers, and the like. His definition of exploitation (Cohen, section 3) was explicitly about the relation between receipt (“obtain[ing] something”) and contribution (“giving … in return”) or, as he put it, “reciprocity”:

under certain conditions, it is (unjust) exploitation to obtain something from someone without giving him anything in return. To specify the conditions, and thereby make the premise more precise, is beyond the concern of this essay. A rough idea of exploitation, as a certain kind of lack of reciprocity, is all that we require.

Furthermore, the “Plain Argument” was a purported proof that capitalists exploit workers in the specific sense indicated above. The argument was that “the labourer is exploited by the capitalist” because “[t]he labourer receives less value than the value of what he creates,” while “[t]he capitalist receives some of the value of what the labourer creates” (Cohen, section 8). Cohen did not prove this, but he did at least stay on-topic.

Ben Burgis

Section 3: Burgis on Capitalist Control of “Part of the Product”

The theory of exploitation that Burgis 2022 puts forward rides roughshod over the facts of capitalist production. It also rides roughshod over Marx’s theory. I will deal first with the facts.

The Facts

According to Burgis, capitalist production is exploitative because “workers are forced to … give up the part of the product of their labor that isn’t under their control.” He thus contends that (a) one part of the product of workers’ labor is under their control, but another part is not, and (b) the workers “give up” the latter part.

Both (a) and (b) are false.

In a moment, I will explain why they are false. But before I do so, I want to make clear that I am not distorting Burgis’ theory by taking a single inapt formulation out of context. He conflates the issue of exploitation with the issue of who controls the product, not once, but again and again.[3] And he claims, not once, but again and again, that workers surrender part of the product:

… the traditional socialist charge that workers are exploited under capitalism is easy to understand: workers produce value but capitalists control how much of it is returned to them in wages.

… The key point is that workers are the source of the products that have value and capitalism systematically forces them to surrender some of that value to the boss.

… [There is a] disconnect between the part of a firm’s revenues that goes into workers’ wages and the part that isn’t under their control.

… Pro-capitalist economists like to [point out that …] workers only supply one of the three factors [of production, but this] hardly rebuts the charge that workers don’t control the products of their labor.

… the Marxist charge [is] that it’s exploitative for workers not to control the output of their labor[.]

…. As with feudal peasants, workers are deprived of control over the product ….

… What makes the surrender of some of the value produced by workers or the value of the commodities they produce exploitation is … it’s taken as a result of the power one class has over another.

The real question, then, is whether the part of the value controlled by the capitalist is voluntarily surrendered by the worker.

… [Workers’] surplus labor … goes not toward meeting their own needs but toward the remainder of a firm’s revenues, which, whether kept by the capitalists or reinvested, is outside of the workers’ control.

What is wrong with this picture?

Despite what Burgis claims, workers in capitalist production do not control, or own, any of the products that their labor helps to produce. They have no property rights to any of it. None of the products that are produced belong to the workers. All of them belong to the businesses that hire the workers.

Since workers do not own or control any of the products, they do not “give up” or “surrender” a part of the products to capitalists. You can’t surrender control, or ownership, of things that you never controlled or owned in the first place.

Nor is it the case that some of what workers produce is “returned to them in wages.” That claim is wrong for two reasons.

First, when Burgis claims that workers produce products that have value, and that their wages “return” part of that value to them, he is implying that workers and businesses share the proceeds. That is not the case. To repeat: all of the proceeds belong exclusively to the businesses. What workers are paid is not a share of the proceeds. Most are paid time wages (hourly wages, weekly wages, etc.), so their pay reflects the amounts of time they work, not the number of products they help to produce or the sales revenue that the businesses obtain by selling the products. It is true that other workers are paid piece rates, but the result is the same. The piece-rate pay received by a worker who delivers Domino’s pizzas depends on how many deliveries he or she individually makes, not on the size of the total product––the number of pizzas that Domino’s produces––or the revenue that Domino’s receives from selling them.

Second, nothing is “returned” to workers after the fact, once production is concluded. Their wages and benefits are not a portion of the products’ value. It is true that workers generally receive their wages and benefits only after they have completed their work, but this does not alter the fact that their rate of pay (per hour, per piece, etc.) is fixed by an explicit or implicit contract ahead of time, before production begins. The businesses that employ the workers have a legal obligation to pay them those prespecified amounts.

Marx’s Theory

It is important to note, first of all, that Marx was well aware of the facts, and that his exploitation theory of profit took due account of them. Unlike Burgis, Marx did not claim that workers control (or own) any of the products their labor helps to produce. Nor did he claim that workers “surrender” some portion of the products, or their value, to capitalists. To the contrary, Marx repeatedly and explicitly stated that the products belong exclusively to the capitalists. In chapter 7 of Capital, volume 1, he wrote that the capitalistic labor process “exhibits two characteristic phenomena,” one of which is that

the product is the property of the capitalist and not that of the labourer, its immediate producer. Suppose that a capitalist pays for a day’s labour-power at its value; then the right to use that power for a day belongs to him, just as much as the right to use any other commodity …. The labour-process is a process between things that the capitalist has purchased, things that have become his property. The product of this process belongs, therefore, to him, just as much as does the wine which is the product of a process of fermentation completed in his cellar. [emphases added]

In chapter 24, Marx reiterated that

At first the rights of property seemed to us to be based on a man’s own labour. … Now, however, property turns out to be the right, on the part of the capitalist, to appropriate the unpaid labour of others or its product, and to be the impossibility, on the part of the labourer, of appropriating his own product.

… the original conversion of money into capital is achieved in the most exact accordance with the economic laws of commodity production and with the right of property derived from them. Nevertheless, its result is:

(1) that the product belongs to the capitalist and not to the worker;

(2) that the value of this product includes, besides the value of the capital advanced, a surplus-value which costs the worker labour but the capitalist nothing, and which none the less becomes the legitimate property of the capitalist; ….

… The surplus-value is [the capitalist’s] property; it has never belonged to anyone else. [emphases added]

Furthermore, Marx heaped scorn on anything that would suggest––as Burgis does when he writes that part of what workers produce is “returned to them in wages”––that the worker and the capitalist share the proceeds of production. In chapter 18 of volume 1 of Capital, Marx even criticized the practice of expressing profit and wages as shares of the new value created (e.g., “the profit share is 35%,” “the wage share is 65%”). He argued that such expressions conceal the fact that all of the product belongs to the capitalist, none to the worker:

The habit of representing surplus-value and value of labour-power as fractions of the value created … conceals the very transaction that characterizes capital, namely the exchange of variable capital for living labour-power, and the consequent exclusion of the labourer from the product. Instead of the real fact, we have [the] false semblance of an association, in which labourer and capitalist divide the product …. [emphases added]

Marx also addressed the issue that wages are generally paid only after production is completed. He did not conclude from this that wage payments “return” to workers a part of what their labor has helped to produce. To the contrary, he argued that the timing of wage payments makes no difference, since the amounts workers are to be paid is stipulated by contract prior to production. For example, in chapter 6 of Capital, volume 1, Marx wrote that

[i]n every country in which the capitalist mode of production reigns, it is the custom not to pay for labour-power before it has been exercised for the period fixed by the contract, as for example, the end of each week. … Nevertheless, whether money serves as a means of purchase or as a means of payment [i.e., whether wages are disbursed immediately or payment of wages is deferred until later], this makes no alteration in the nature of the exchange of commodities. The price of the labour-power is fixed by the contract, although it is not realised till later, like the rent of a house. The labour-power is sold, although it is only paid for at a later period.

In sum, Burgis either does not understand, or he has intentionally chosen to distort, Marx’s theory that, under capitalism, labor-power is a commodity. Burgis is able to define “labor power” and to inform us that it is commodified; he writes that “a worker’s capacity to work––her ‘labor power’––is a ‘c’ [commodity].” But his article provides no indication that he understands what this implies. The things I have been discussing––that the whole product and its whole value belongs to the capitalist, that workers and capitalists do not share the proceeds, and that wage payments purchase labor-power instead of “returning” to workers some of the value of the products––are the most immediate, surface-level implications of the fact that labor-power is a commodity.

Burgis’ Concept of Exploitation and the Dynamics of Class Struggle

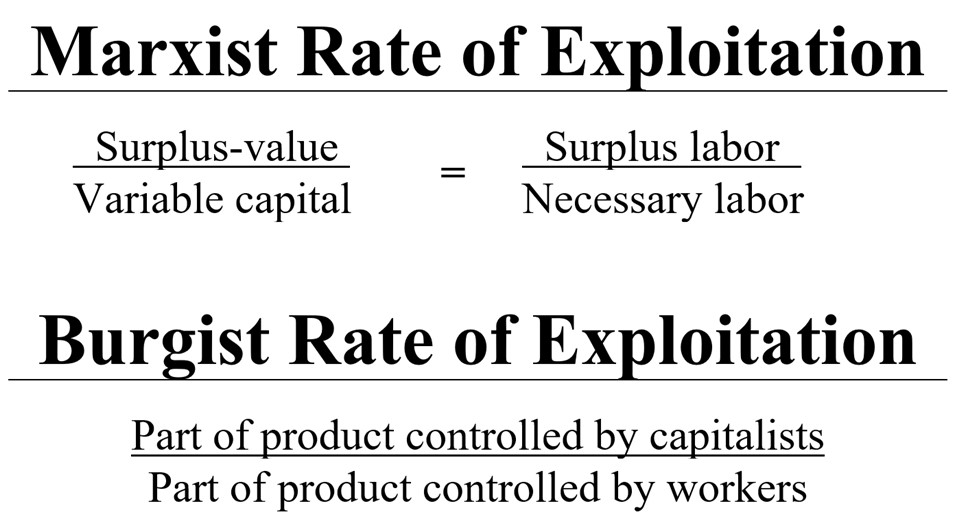

In Marx’s original theory, the rate of surplus-value is the ratio of surplus-value to variable capital. Equivalently, it can be expressed as the ratio of surplus labor to necessary labor (see Figure 1).[4] Since Marx argued that “[t]he rate of surplus-value is … an exact expression for the degree of exploitation of labour-power by capital, or of the labourer by the capitalist,” the rate of surplus-value is often called the rate of exploitation.

Figure 1

What Burgis proposes is, inadvertently, quite different. He wants to make exploitation synonymous with capitalist control (and ownership) of the product. So he substitutes “the part of the product controlled by capitalists” for surplus-value and surplus labor, and he substitutes “the part of the product controlled by workers” for variable capital and necessary labor. Burgis’ implicit alternative to the Marxist rate of exploitation is thus the ratio of these two “parts.”

His substitutions have some strange consequences. Since Burgis fails to recognize the obvious fact that capitalists control and own the whole product, he is almost certainly unaware of the consequences.

In Marx’s theory, when workers’ struggles for a shorter workday (or workweek) are successful, this reduces the amount of surplus labor the workers perform. It reduces the amount of surplus-value they create. And it reduces the rate of exploitation. Similarly, if they obtain higher wages and/or more benefits, necessary labor and variable capital increase, surplus labor and surplus-value decrease, and the rate of exploitation falls. A longer workday (or workweek), or a reduction in wages or benefits, would have the opposite effects.

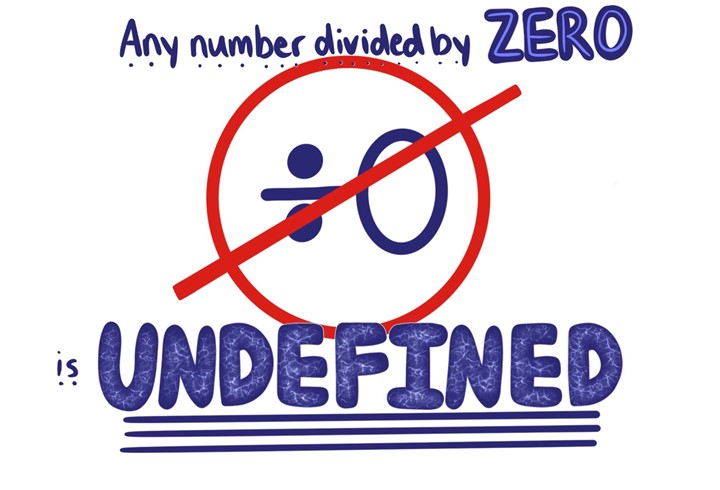

Burgis’ control-centric notion of exploitation fails to capture these basic dynamics of class struggle. The failures become obvious the moment we recognize the fact that the whole product is controlled and owned by capitalists.

First of all, the Burgist rate of exploitation is a non-starter. It does not increase when the workweek is lengthened or employee compensation is cut, and it does not decrease when the workweek is shortened or employee compensation rises. Since its denominator, the part of the product controlled by workers, is always zero, this rate of exploitation is always “undefined”––in other words, meaningless. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

Second, Burgis’ redefinition of exploitation implies that workers are not less exploited if they obtain higher wages and/or more benefits, nor more exploited if wages or benefits are cut. Why not? Well, the whole product was under the exclusive control of the capitalists before employee compensation rises or falls, and it remains under their exclusive control thereafter, so there has been no change in the amount of exploitation.[5]

Can Burgis’ redefinition of exploitation at least capture the effects of changes in the length of the workday or workweek? It depends, because “the part of the product controlled by capitalists” can mean either the share of the product, or the absolute amount of products, that they control. If we take “the part” to mean “the share,” Burgis’ redefinition implies that changes in length of the workday or workweek have no effect on the amount of exploitation, since capitalists control 100% of the product both before and after working time changes.

However, a rise or fall in working time causes the absolute amount of products produced, and therefore the absolute amount of products controlled by capitalists, to rise or fall as well. So if we take “the part” to mean “the absolute amount,” Burgis’ notion of exploitation does imply that the changes in working time affect the amount of exploitation. However, this latter interpretation of “the part” has some strange consequences of its own.

Imagine, for instance, that workers are made to work overtime. The workweek is lengthened, and thus more products are produced. But if the workers’ overtime pay rate is very high relative to their base pay, their overtime pay can in principle exceed the additional amount of new value that their overtime work creates. In this case, necessary labor and variable capital rise while surplus labor and surplus-value fall. Thus, Marx’s theory implies that the amount of exploitation has decreased. Yet capitalists control the whole product, and the lengthening of the workweek has caused the absolute size of the product to expand. So if “the part” means “the absolute amount,” Burgis’ notion of exploitation implies that the amount of exploitation has increased!

It also implies that the amount of exploitation will change even when there is no change in the length of working time or in workers’ pay. The absolute amount of products produced, and thus the absolute amount of products controlled by capitalists, changes with every change in productivity––that is, with every change in amount of physical output, per unit of labor. The amount of exploitation will change even if the change in output cannot in any way be attributed to workers’ labor. Consider, for example, good or bad weather that results in greater or smaller crop yields, or fish or rabbits that breed more or less rapidly than they did previously, or software that improves through machine learning, or earthquakes, power outages, and the like that destroy products sitting in warehouses. The absolute amount of products that capitalists control changes in all such cases. So if “the part” means “the absolute amount,” then the amount of exploitation as redefined by Burgis changes as well, even though workers’ pay and the amounts of work they do remain unchanged.[6]

The fundamental problem––the source of all these strange consequences––is Burgis’ failure to recognize the distinction between exploitation and control of the product. Because he conflates these two things, he is obliged to conclude that, whenever capitalists have exclusive control of the product (of a given size), the extent to which workers are exploited is always the same. Changes in working hours and pay do not matter. All that matters is that capitalists control the whole product. Since capitalists’ exclusive control of the product is an invariable fact of capitalist production, the extent of exploitation as redefined by Burgis becomes invariable as well.

In contrast, Marx’s theory respects the distinction between exploitation and control. Precisely because it does not conflate them, it is able to recognize that, while capitalist ownership/control and domination are invariable features of capitalist production, the amount and degree of exploitation are nonetheless variable. Indeed, Marx’s theory even recognizes that capitalist ownership/control without exploitation of labor is logically possible (though not economically sustainable). If workers’ wages and benefits were equal to the amount of new value their labor creates, then there would be no exploitation––no surplus labor, no surplus-value––even though capitalists would continue to control and own the whole product, and their managers would continue to dominate the workers.

My point here is not that control (or ownership, or domination) is unimportant. Nor am I claiming that control and exploitation are completely separate things. Capitalist control of the product is certainly a necessary condition for exploitation of proletarians’ labor (and, indeed, for the very existence of a class of proletarians). And changes in the ways that capitalists exercise their control of the product can influence the absolute amount and degree of exploitation. My point is simply that exploitation of labor and capitalist control of the product are not identical concepts.

G. A. Cohen

Section 4: The Context of Cohen’s “Plain Argument”

Cohen’s Goal and Strategy

Cohen was an “analytical Marxist” philosopher. His “Plain Argument” paper was a classic example of the “analytical Marxism” project, which was dedicated to steering left-leaning intellectuals away from Marx’s own Marxism, much of which it denounced as “bullshit.” In this case, Cohen was trying to steer left-leaning intellectuals away from Marx’s argument as to how workers are exploited by capitalists. He did this by putting forward a (bogus) refutation of Marx’s own argument and then offering the “Plain Argument” as an alternative.

Cohen’s message to his audience was: I’ve disproven the exploitation theory that you have thought you accept, but not to worry! It’s no skin off your noses, because you have never actually accepted Marx’s own argument. What you have believed all along is the “Plain Argument.” It is “the real basis of the Marxian imputation of exploitation to the capitalist production process, the proposition which really animates Marxists, whatever they may think and say” (Cohen, section 8).

On the surface, the “Plain Argument” seems similar to Marx’s argument, but in fact “[t]he arguments are totally different,” as Cohen (section 8) stressed. Marx’s argument regarding capitalist exploitation was that workers’ labor is the only thing that creates new value, while capitalists receive a portion of that value. But, Cohen said, the “Plain Argument”––the one you actually believe in, whether you know it or not––has nothing to do with labor being the only thing that creates value. Indeed, it does not even say that value is something that is created. Its major premise is “a fairly obvious truth which owes nothing to the labour theory of value” (Cohen, section 8).

What you actually believe, Cohen continued, is that workers are the only people who create new physical products, while capitalists receive a portion of these physical products. Of course, these physical products have value and capitalists receive a portion of that value, but this simply does not imply that the workers’ labor is what creates the products’ value. It doesn’t even imply that the value of a product is something that is created at all. (Its value might instead be something it acquires when it is bought, by virtue of being bought, as “value-form” theorists like to argue.) Thus, what you actually believe, Cohen said, “is not that the capitalist gets some of the value the worker produces, but that he gets some of the value of what the worker produces” (Cohen, section 8, emphasis in original). “The small difference of phrasing covers an enormous difference of conception” (Cohen, section 8).

Burgis 2019 claimed that Cohen’s “Plain Argument” is in fact Marx’s own “theory of exploitation”: “As the great 20th-century Marxist philosopher G. A. Cohen persuasively argues in the final sections of his paper “The Labour Theory of Value and the Concept of Exploitation,” Marx’s theory of exploitation is logically detachable from his theory of value” (emphasis added). What “logically detachable from his theory of value” means is that, while Marx expressed his “theory of exploitation” using concepts from his value theory, the value theory can be set aside and “Marx’s theory of exploitation” can be restated in other terms, without altering its content. The reconstructed theory of exploitation uses different language, but it remains Marx’s own theory as far as its content is concerned. Not only is the conclusion of the reconstructed theory, that workers are exploited by capitalists, the same as Marx’s. The theory itself––its arguments and the evidence that supports them––is still Marx’s as well.[7]

This was certainly not Cohen’s own view. He knew full well that his essay was an attack on Marx’s own theory. As we have just seen, Cohen made it crystal clear that his “Plain Argument” regarding exploitation was not Marx’s exploitation theory, but an alternative to it, and that the conceptual difference between the two theories is “enormous” (Cohen, section 8). As we shall see later in this section, Cohen’s essay also went to some length to try to prove that Marx’s theory is self-contradictory and therefore untenable.

Cohen’s Audience

Cohen was quite right about the mindset and the misconceptions of his audience. The garden-variety Marxists who supposedly embrace Marx’s exploitation theory have rarely had much interest in, or understanding of, the value theory in which it is grounded. Although they have accepted “Marx’s” exploitation theory, that is just because they have failed to recognize the difference between creating value and creating products that have value. What these garden-variety Marxists have cared about is allegedly “unjust” income distribution and private property, which they find deeply offensive. And the “Plain Argument” aptly expresses their gut intuition that workers are entitled to the whole product because they produce the whole product.

But the “Plain Argument” does more than give voice to their gut intuition. By means of its numbered sentences, its “therefore” dot triangles, and––above all––its pseudo-logical hocus-pocus, the “Plain Argument” transforms their gut intuition into a reasonable facsimile of an honest-to-goodness theoretical argument. It seems, at first glance, to be a handy substitute for Marx’s own argument, a logical argument that strips away his fancy-schmancy value jargon and replaces it with plain English and salt-of-the-earth common sense. It seems to be an argument that can, and should, win the adherence of all the garden-variety Marxists who have never really cared about all of that value stuff anyway. In fact, it seems that the “Plain Argument” should win the adherence of every thinking person, since its premises are uncontroversial and Cohen seems to have proven that the premises necessarily lead to the conclusion that workers are exploited by capitalists.

When one looks at it even a bit closely, however, it becomes clear that the “Plain Argument” is just plain bad. It is a logically invalid argument: even if all of the premises with which it begins are true, that doesn’t guarantee that its conclusion is true. In other words, the “Plain Argument” fails to deduce the conclusion from its premises. Since it is a deductive argument, this is a fatal flaw. The job of a deductive argument is precisely to deduce its conclusion from its premises.

Analyze This, Jerry!––On Cohen’s “Proof” that Labor Doesn’t Create Value in Marx’s Theory

Prior to offering the “Plain Argument,” Cohen set out to demolish Marx’s own exploitation theory. He faced an audience which thought that it liked Marx’s theory. So Cohen wanted to soften up his audience, to make it more receptive to the “Plain Argument.” Demolition of Marx’s theory was a perfect way to soften it up. Once Marx’s theory was eliminated, anyone who still wanted to argue that workers are exploited would have to turn to the “Plain Argument” or something like it.

Cohen claimed that Marx’s own exploitation theory is untenable because it is self-contradictory. Marx’s conclusion, that capitalists exploit workers, depends on his premise that workers’ labor is the only thing that creates value. However, Cohen asserted and purported to prove that Marx’s value theory––the “strict doctrine” (Cohen, section 5) rather than the popular version––actually implies that labor does not create value.

His alleged proof began by establishing two things. First, the strict doctrine says that a commodity’s value is determined by the socially necessary amount of labor that is currently required to produce a commodity of that kind. Second, “[t]he amount of time required to produce it in the past, and, a fortiori, the amount of time actually spent producing it[,] are magnitudes strictly irrelevant to its value” (Cohen, section 5). So far, so good.

Cohen then wrote, “But past labour [i.e., the amount of time required to produce the commodity in the past] would not be irrelevant if it created the value of the commodity. It follows that labour does not create value, if the labour theory of value is true (Cohen, section 5).

No, it doesn’t follow. Not at all.

Marx’s theory does say that the amount of time required to produce the commodity in the past is irrelevant to its current value, but this does not negate the proposition that past labor created the commodity’s value. It is possible that both things are true––past labor created the commodity’s value, yet past labor is irrelevant to its current value. There is simply no contradiction between past creation and current irrelevance. Thus, when Marx affirmed both past creation and current irrelevance, he was not contradicting himself. His “strict doctrine,” which denies that past labor is relevant to a commodity’s current value, is fully compatible with the “popular doctrine,” that labor creates value, on which his exploitation theory depends. They are not even distinct doctrines, but instead two aspects of a single theory.

Cohen’s proof fails because his argument disregards the distinction between the determination of a commodity’s value and the creation of its value. There are more things in heaven, earth, and Marx’s theory, Jerry, than are dreamt of in your analytical philosophy. In Marx’s theory, a commodity’s value is created once, when the commodity is produced. The living labor expended on the commodity’s production creates its value (or, more precisely, the difference between its total value and the value transferred to the product from used-up means of production). But the determination of a commodity’s value––the original determination of its value, at the moment of its production, as well as all of the subsequent revaluations––is an ongoing process. It comes to an end only when the commodity itself ceases to exist. There is no contradiction between these propositions. The revaluations alter the commodity’s current value. But they do not retroactively alter the amount of value that was created in the past. That would be absurd. What’s done is done.

So Cohen failed to show that there is anything wrong with Marx’s exploitation theory. And because his proof failed, he also failed to show that we need his “Plain Argument,” or something like it, as a substitute for Marx’s own theory.

But why does Marx’s exploitation theory of profit invoke the “popular” proposition that labor creates value, rather than the “strict doctrine”? Cohen suggested that the reason is that the popular version fulfills “political functions” (Cohen, section 5) or otherwise makes an untenable theory seem plausible. But the real reason is simpler and less nefarious: the determination of a commodity’s value after it is produced––that is, the phenomenon of revaluation––is irrelevant to the issue of exploitation and to Marx’s explanation of the source of profit. What is relevant to them is creation of value.

In Marx’s theory, the exploitation of the worker––the extraction of surplus labor––takes place, once and for all, in the process of production. The monetary expression of the surplus labor––the surplus-value or profit––is created, once and for all, in this process of production. Subsequent revaluations have no bearing on the matter. They cannot retroactively alter either the total amount of time the worker worked or the “necessary labor” and “surplus labor” portions of that working time. And although subsequent revaluations alter the value of produced goods that businesses hold in inventory, and this affects their current profits (if we count all changes in businesses’ wealth as changes in profits), they do not retroactively alter either the value that those goods had at the conclusion of the production process or the portion of that value that represented surplus-value or profit.[8]

Section 5: Cohen’s Just Plain Bad Argument

Logically Invalid––So What? Who Cares?

I shall presently show that the “Plain Argument” is logically invalid. So what? Who cares?

I care, for ethical and political reasons. I think everyone else should also care, for the same reasons.

The ethical reason is that “it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence,” as the mathematician and philosopher W. K. Clifford masterfully argued in his 1877 essay, “The Ethics of Belief.” If a deductive argument is valid, the argument itself is sufficient evidence that its conclusion necessarily follows from its premises. If the premises are all true, the conclusion is also true, and thus it is right to believe the conclusion. In contrast, an invalid deductive argument, like Cohen’s “Plain Argument,” does not constitute evidence that its conclusion is true. It is therefore wrong––always, everywhere, and for anyone––to believe that workers are exploited by capitalists, unless the belief is based on other evidence, sufficient evidence, instead of Cohen’s argument.

It follows from this that anyone who makes an invalid deductive argument in an attempt to persuade you is trying to get you to believe something you should not believe, since you have no more evidence that the argument’s conclusion is true than you did before. If they do this knowingly, they are trying to manipulate you and hoodwink you.

The political reason to care about this is that the fight for Clifford’s ethics of belief––which includes fighting back against invalid arguments––has become a political imperative of the highest priority. The threat from Trumpism and its Big Lie about the stolen 2020 election, and the threats from QAnon, anti-vaxx, and other conspiracy mongering as well as the whole “post-truth” ethos, are what have made it a political imperative.[9] We would be in a much better place, under much less threat, if the cultural norm of tolerating belief that is not backed up by sufficient evidence gave way to a norm of exposing, denouncing, and ridiculing it. We would be in a much better place, under much less threat, if enough people were to repudiate the harmful maxim that “you’re entitled to your own opinions, but not your own facts” and instead embrace the maxim that “you’re not entitled to your own facts––and, if you lack sufficient evidence for your beliefs, you’re not entitled to them, either.”

What’s Wrong with the “Plain” Argument?

At the end of Section 8 of his paper, Cohen presented the “Plain Argument”:[10]

(1) The labourer is the only person who creates the product, that which has value.

(2) The capitalist receives some of the value of the product.

∴ (3) The labourer receives less value than the value of what he creates, and

(4) The capitalist receives some of the value of what the labourer creates.

∴ (5) The labourer is exploited by the capitalist.

To understand the argument, we first need to understand what Cohen meant by “exploited,” “labourer” and “creates.” As I discussed above, he had already defined exploitation as a disproportion between receipt and contribution––“obtain[ing] something from someone without giving him anything in return” (Cohen, section 3). And immediately before presenting the “Plain Argument,” he clarified what he meant by “labourer” (producer, worker) and “creates” (produces):

workers … create the product. …

Or, to speak with greater care, producers are the only persons who produce what has value: it is true by definition that no human activity other than production produces what has value.

…. An owner of capital can, of course, also do some producing, for example, by carrying out a task which would otherwise fall to someone in his hire. Then he is a producer, but not as an owner of capital. More pertinent is the objection that owners of capital, in their very capacity as such, fulfil significant productive functions, in risking capital, making investment decisions, and so forth. But whether or not that is true, it does not entail that they produce anything in the importantly distinct sense in issue here. [Cohen, section 8, emphases added]

Thus, any person who (directly) produces a product that has value is a producer (worker, laborer) by definition. In other words, when the “Plain Argument” refers to “the labourer,” what it means is any person who (directly) produces a product that has value. An owner of capital is a labourer, in the sense defined, if and insofar as he (directly) produces the product, but not otherwise.

The above passage also specifies what the “Plain Argument” means by the term “creates.” It means directly produces, and nothing more. A person whose activities contribute to production––“fulfil significant productive functions”––but who does not directly produce products, is not someone who “creates the product” or who functions as a labourer in Cohen’s sense.

In light of these definitions, Step (1) of the “Plain Argument” is unproblematic, because it is true by definition. Cohen’s definitions tell us that “The labourer is the only person who creates the product” has the following meaning: “Only the person who directly produces the product is the person who directly produces the product.” This is a tautology; it therefore has to be true. However, notice that, given Cohen’s definitions, Step (1) does not assert that workers (or owners of capital functioning as workers) are the only people whose activities make a contribution to production. Nor does it say that the laborer and nothing else creates the product. That is, it does not deny that nonlabor inputs to production (machinery, land, materials, etc.) also produce (create) the product.

Step (2) is unproblematic because it is a correct statement of fact.

The problems begin with Step (3). It is allegedly deduced from (1) and (2), but it does not actually follow from them. The move is logically invalid. (The logically valid deduction from (1) and (2) is that the laborer receives less value than the value of the product that no person other than the laborer creates.) In (1), we are told that the laborer is “the only person who creates,” while in (3) we are told that “he creates.” The latter is not innocent shorthand. Step (1) is fine, because it does not say that the laborer and nothing else produces the product. However, by shifting to the “he creates” formulation, Step (3) does implicitly attribute the product’s production exclusively to the laborer. It therefore implies that nonlabor inputs do not also produce the product, which is false.

To see the implications of this move, let us reformulate the “Plain Argument” without it. And let us acknowledge from the outset the productive role of nonlabor inputs, which Step (1) does not mention explicitly but also does not deny. We then have:

(1*) The labourer is the only person who creates the product, that which has value. Nonlabour inputs also create the product, that which has value.

(2) The capitalist receives some of the value of the product.

∴ (3*) The labourer receives less value than the value of what he and the nonlabour inputs create, and

(4*) The capitalist receives some of the value of what the labourer and the nonlabour inputs create.

∴ (5*) No conclusion about exploitation of the labourer by the capitalist can be derived from the definitions and propositions above.

One reason no such conclusion can be derived is that, given Cohen’s definition of exploitation as a disproportion between receipt and contribution, the laborer is exploited by the capitalist only if he receives less value than the value of what he, rather than the nonlabor inputs, creates. But that is not what (4*) says. Assume that the value of the product jointly created by the laborer and the nonlabor inputs is $100, that the laborer receives $70, and that the capitalist receives $30. Then the laborer is exploited only if the portion of the value of the product that is attributable to the laborer’s activity rather than to the productive role of the nonlabor inputs is greater than $70. If the portion of the product’s value attributable to the laborer’s activity is $70 or less, he has not been exploited by the capitalist. (I shall leave aside the issue of how––and whether––it is possible to attribute portions of the product’s value in this manner.)

But there is also another reason that no conclusion about exploitation can be derived from the logically valid reformulation of the “Plain Argument.” Recall that Cohen defined exploitation as a disproportion between receipt and contribution, not as a disproportion between receipt and direct production of products. And recall that Cohen, and Step (1), leave open the possibility that capitalists make a contribution to production––“fulfil significant productive functions”––by “risking capital, making investment decisions, and so forth” (Cohen, section 8) even though they do not directly produce products. If a capitalist does make such a contribution to production, then he would be exploited, according to Cohen’s own definition, if he failed to receive a portion of the product’s value proportionate to the contribution he made. For example, if the laborer receives $100, an amount equal to the product’s full value, none of its value is left over for the capitalist to receive. It follows that the laborer has exploited the capitalist.

But wait, there’s more! Other entities can also make contributions to production. To take just one example, governments contribute to production by providing a legal framework within which it can take place.

In short, the “Plain Argument’s” conclusion that the laborer is exploited by the capitalist requires a previous step that is not only much stronger than Step (4*) but stronger than Cohen’s own Step (4) as well:

(4**) The capitalist receives some of the portion of the product’s value that is attributable to the labourer’s activity rather than to the productive role of nonlabor inputs, or to the capitalist’s own contribution to production, or to contributions to production made by other entities.

Nothing remotely like (4**) follows from the parts of the “Plain Argument” that are true, Steps (1) and (2). And once we reinstate the productive role of nonlabor inputs––which Step (3) of the “Plain Argument” cleverly conjured away––and we bear in mind Cohen’s definition of exploitation––which the “Plain Argument” fudged by referring to creation of products instead of contributions to production––here is what we get:

(4***) The capitalist receives some of the value of the product. Its total value is the sum of the portion attributable to the labourer’s activity, the portion attributable to the productive role of the nonlabour inputs and, possibly, portions attributable to the capitalist’s own contribution to production and/or the contributions that other entities make. The portion of the value that the capitalist receives may or may not include some of the value attributable to the labourer’s activity.

The only thing that follows from this mouthful is:

(5***) The labourer may or may not be exploited by the capitalist.

Quod erat demonstrandum, non demonstratum.

Contributions Made by Suppliers of Inputs and by Lenders

I have noted that nonlabor inputs contribute to production by directly producing products (in conjunction with workers). There are, in addition, contributions to production that suppliers of nonlabor inputs make. I do not mean that the inputs’ contribution to production is somehow also the suppliers’ contribution. It is not. The nonlabor inputs “create the product,” but their suppliers do not. The suppliers’ contribution to production is indirect: they relinquish ownership/control of their inputs and thereby make them available to business firms engaged in production. In everyday language, we describe this by saying that the suppliers rent or sell the inputs. And that is true, but it does not capture another truth: the money that the suppliers obtain by renting or selling the inputs is what they receive in return for making the inputs available for use in production.

The contribution of lenders (who Cohen described as capitalists that arguably “risk capital”) is analogous. They indirectly contribute to production by making funds available to firms engaged in production, and the interest and repaid principal they obtain through lending is what they receive in return for making the funds available.

Let me make clear what I have not said. I have not said that the portion of a product’s value that is attributable to the contributions made by suppliers of nonlabor inputs is necessarily equal to the portion of its value that is attributable to the productive role of the inputs themselves. I have not said that moneylenders “risk capital,” so I have also not said that the interest they receive is a return for risking capital. I have not said that there is no alternative way to make funds and nonlabor inputs available to producing entities, so I have also not said that the existence of moneylenders and capitalists who supply inputs is necessary in all forms of society. I have not said that moneylending and private ownership of nonlabor inputs are just, nor have I said that they are unjust.

I am not talking about justice and injustice at all. I am talking about exploitation, as the term is commonly defined and as it was defined in Cohen’s “Plain Argument” essay. And I am talking about exploitation in situations where nonlabor inputs and funds owned/controlled by capitalists are among the initial conditions.

The secret of Donald J. Trump’s profit-making must at last be laid bare. He stiffs his creditors, his suppliers of faux marble, and so on, eventually settling to pay back 30 cents on the dollar or whatever. He obtains something from them (70 cents per dollar or whatever) without giving them anything in return. This is exploitation. And it is exploitation as Cohen himself defined the term. Of course, it isn’t exploitation in the process of production, extraction of surplus labor, creation of surplus-value. But it is exploitation nonetheless, given the initial condition that the funds and faux marble were owned/controlled by capitalists other than Trump.

Section 6: Cohen’s and Burgis’ Evaluations of the “Plain Argument”

Cohen’s Evaluation

When Cohen put forward the “Plain Argument,” he was not trying to persuade his audience to accept it. As we have seen, his goal was to explain to garden-variety Marxists that they already accept the “Plain Argument,” even though they mistakenly think that what they accept is Marx’s own exploitation theory. The “Plain Argument” is what “really animates Marxists, whatever they may think and say” (Cohen, section 8).

But did Cohen himself accept the “Plain Argument”? His essay provides no evidence that he did so. He explicitly stated at the end that he was refraining from endorsing the “Plain Argument”:

I have argued that if anything justifies the Marxian charge that the capitalist exploits the worker it is the true proposition [1], that workers alone create the product. It does not follow that [1] is a sound justification, and that the Plain Argument, suitably expanded, is a good argument. Having disposed of the distracting labour theory of value, I hope to provide an evaluation of the Plain Argument elsewhere. [Cohen, section 10, emphases added, proposition number altered]

This statement was a clear warning to readers that it would be wrong to assume that Cohen himself thought that the “Plain Argument” was a good one. He had not said that and he had not implied it. He had not provided his own evaluation of the “Plain Argument” at all.

Yet the most striking evidence of Cohen’s non-endorsement of the “Plain Argument” is the fact that his essay points out one of its major defects. As we have seen, he called attention to an objection to the “Plain Argument’s” conclusion that capitalists exploit workers, “the objection that owners of capital, in their very capacity as such, fulfil significant productive functions, in risking capital, making investment decisions, and so forth” (Cohen, section 8).

Cohen then commented that “I here neither assert nor deny” that the objection is correct, and that, if it is indeed correct, then “that will have a bearing on the thesis that [the capitalist] is an exploiter. It will be a challenge to [the Plain Argument’s] charge of exploitation” (Cohen, section 8). Thus, in addition to calling attention to one of the most serious objections to the “Plain Argument,” Cohen intentionally refrained from arguing against it, and even from saying that it is incorrect. His essay took an agnostic position.

Burgis’ Continuing Embrace of the “Plain Argument”

Since the “Plain Argument” is only five lines long, it is pretty easy to spot the holes in it. I was therefore rather surprised when I learned that Burgis endorsed it. One reason I was surprised is that Cohen himself had not endorsed the “Plain Argument.” The other reason is that Burgis is not only a trained philosopher, but a specialist in logic, and in other contexts he seems to be a competent logician.

I therefore attempted to explain to Burgis how and where the “Plain Argument” goes wrong, in the June 25, 2021 episode of the Radio Free Humanity podcast series that I co-host along with Brendan Cooney. This was far more difficult than I thought it would be, but not because the “Plain Argument” is any better than I had thought. The problem instead seems to be that Burgis did not (and apparently still does not) adequately understand it.

There seem to be two main misunderstandings. First, it gradually dawned on me that Burgis misunderstood the “Plain Argument’s” premise that workers are the only people who create the products. When I pointed out that capitalists indirectly contribute to production––by organizing production, and by supplying nonlabor inputs and funds––he responded that they do not create the products, and he suggested that I was saying that capitalists do create the products. Thus, he claimed that I had not shown that the “Plain Argument” is invalid; instead of showing that its conclusion does not follow from its premises, I was merely rejecting the premise that workers are the only people who create the products. I repeatedly responded that I accept that premise, as I do. However, Burgis kept insisting that I do not.

The source of this disagreement clearly seems to be Burgis’ failure to understand what the premise means by “creates the product.” As we have seen, Cohen distinguished between creating the products and contributing to production: although capitalists may possibly “fulfil significant productive functions [… this] does not entail that they produce anything in the importantly distinct sense in issue here” (Cohen, section 8). So when I said that capitalists indirectly contribute to production, I was not claiming that they create the products in Cohen’s sense and I was not rejecting the “Plain Argument’s” premise.

Second, Burgis’ responses to my arguments had little if anything to do with the concept of exploitation employed in the “Plain Argument.” He either misunderstood the definition of exploitation that Cohen had provided or he disregarded it. Below, I will review the ways in which Burgis has defended what he takes the “Plain Argument” to be saying. Here, it is sufficient to note that none of his arguments address whether workers receive less value than the portion of the value of the product that is specifically attributable to their activity. And none of his arguments address whether suppliers of nonlabor inputs and funds, and capitalists who organize production, would be giving something without receiving something proportionate in return if workers were to receive the whole value of the product. In short, Burgis’ arguments do not go to the question of exploitation when it is defined as disproportion between contributions and receipts.

Burgis’ Defenses of the “Plain Argument”

A. Burgis argues against a hypothetical claim that “capitalists have a moral right to extract some of what’s produced by workers in a way that feudal lords didn’t have a moral right to extract part of what was produced by peasants” (Burgis 2019, emphasis in original). He responds that a capitalist who supplies wood that workers use to make tables is an “unnecessary intermediary”:

the trees were almost certainly chopped down and the wood cut up … by other workers. As the Marxist economist Richard Wolff likes to put it, a capitalist is a well-paid but unnecessary intermediary between two groups of workers” [Burgis 2019]

This may or may not be a good response to the claim about capitalists’ moral right, but it has nothing to do with the concept of exploitation that Cohen employed in his “Plain Argument” paper. Whether the capitalist in Burgis’ example is necessary or unnecessary is irrelevant to the question of whether he would be exploited, in Cohen’s sense, if he did not receive a portion of the table’s value that is proportionate to his contribution to production (the act of making available to the table-making enterprise the wood he owns/controls). Furthermore, the claim that capitalists are just middlemen who skim off profits, but do nothing to assist the production process, is false. In addition to supplying nonlabor inputs and funds, capitalists make investment decisions and organize production.

B. After noting that the role of a capitalist is different from the role of a manager, Burgis writes,

Fine, a defender of capitalism could argue, but aren’t capitalists still making an important contribution by hiring the managers that oversee the production process? [Burgis 2022]

Just who are the strawman defenders of capitalism who “could” make this argument? I have never encountered one. Burgis sidesteps the real, non-stupid arguments offered in support of the idea that capitalists make an indirect contribution to production: they make nonlabor inputs and funds available to businesses engaged in production, organize production, make investment decisions, and so on.

C. Burgis then responds to the strawman argument, after which he writes:

Does ownership of land contribute somehow to production? Only in the sense that the owner permits it to take place. …

The land itself makes a valuable contribution, but how does that refute the Marxist charge that it’s exploitative for workers not to control the output of their labor? As radical scholar David Schweickart argues in his book After Capitalism, unless the idea is that some of the crops produced by the combination of land and agricultural labor are going to [be] burned as a “sacrifice to the God of Land,” the land’s contribution seems rather irrelevant to questions of distribution. [Burgis 2022]

First, I showed in Section 3 that “the Marxist charge” that it’s exploitative for workers not to control the output of their labor was not Marx’s charge. In contrast to Burgis, he did not conflate capitalist exploitation with capitalists’ control of the product. Second, the claim that ownership of land contributes to production is another claim that, to the best of my knowledge, no one makes. Burgis gets closer to a real objection to the “Plain Argument” when he acknowledges the contribution of land to physical production. But he manages to swerve around the real objection by repeating a “joke” that functions as a red herring. The real objection, again, is that the suppliers of nonlabor inputs––in this case, landowners––make a contribution to production by making their inputs available for use in production, and that they would be exploited, in Cohen’s sense, if they did not receive a portion of the product’s value proportionate to this contribution. This is a serious objection. It deserves a serious response, not a red herring “joke” retort.

D. Burgis writes that

any good defender of capitalism will counter that the capitalist provides the physical means of production—the factories, equipment, and so on. Isn’t the capitalist the source of that [surplus-]value? …

Pro-capitalist economists like to talk about “land, labor, and capital” as independent factors that all contribute to production and say that therefore the disconnect between the part of a firm’s revenues that goes into workers’ wages and the part that isn’t under their control is unobjectionable — after all, workers only supply one of the three factors. But if capital means the share of society’s resources (above and beyond what’s present in unaltered nature) used in production, that’s just the fruit of previous labor. It hardly rebuts the charge that workers don’t control the products of their labor. [Burgis 2022]

I have never encountered a “defender of capitalism,” good or not, who suggested that the capitalist is the source of surplus-value––the idea is absurd––and Burgis fails to cite one. Nor do neoclassical economists say that physical means of production are a source of value. They eschew entirely the idea that value is created, or otherwise arises, in the process of production, just as Cohen and Burgis do.

The start of the latter paragraph reports, incompletely but more or less correctly, what many neoclassical economists do say: the employment of an extra unit of an input results in extra physical output, and the value of this extra output is the input’s contribution to production. But Burgis’ response––previous labor is what produced the input––misses these economists’ point completely. The extra physical output that results from employment of an extra unit of a nonlabor input is not “just the fruit of previous labor.” It is newly produced, as should be obvious. Thus, if the value of this extra output is the input’s contribution to the total value of output, as the neoclassicists in question say, it likewise is not the fruit of previous labor.

Having missed the point, Burgis provides no response to it. Yet it is a claim of critical importance to the issue of exploitation. If some of the value of the products is attributable to the productive role of nonlabor inputs, then the fact that workers receive less than the whole value is just not evidence that they are exploited.

What Burgis seems to want to do, in his appeals to previous labor and the fruits thereof, is attribute the value of the extra output to the activity of previous workers rather than to the productive role of the nonlabor inputs: previous workers produced the inputs; the inputs produce the extra output; ergo, previous workers produce the extra output. But since when is “produce” a transitive relation?! The employees of Apple Inc. produce computers, and computers produce Jacobin articles about exploitation, so does Burgis want to say that that the employees of Apple Inc. produce Jacobin articles about exploitation?[11]

Marx took this absurd line of argument to its logical conclusion long ago:

The criminal produces not only crimes but also criminal law, and with this also the professor who gives lectures on criminal law and in addition to this the inevitable compendium in which this same professor throws his lectures onto the general market as “commodities.” This brings with it augmentation of national wealth ….

The criminal moreover produces the whole of the police and of criminal justice, constables, judges, hangmen, juries, etc.; and all these different lines of business, which form equally many categories of the social division of labour, develop different capacities of the human spirit, create new needs and new ways of satisfying them. Torture alone has given rise to the most ingenious mechanical inventions, and employed many honourable craftsmen in the production of its instruments. …

And he went on and on.

In any case, the statement that capitalists receive some of the value of what previous workers create implies something different from what Burgis needs. He is trying to defend the claim that capitalists exploit workers here and now, the workers of today. But if the stuff about previous labor and its fruits is relevant to the issue of exploitation at all, it suggests only that capitalists exploit previous workers. Does Burgis want to say that the workers who mine iron ore are entitled to the value of the ore they produce, plus the value of the pig iron that the ore produces, plus the value of the steel that the pig iron produces, plus the value of the cars that the steel produces, plus the value of the taxi services that the cars produce? And that the autoworkers are entitled to double-dip, the steelworkers to triple-dip, and the ironworkers to quadruple-dip?

Furthermore, some of the previous workers may well be dead.[12] How can the poor capitalist avoid the charge that he is exploiting the deceased? Burn some of the products he owns/controls as a “sacrifice to the Spirit of John Henry”? Ha, ha, ha.

Karl Marx

Section 7: Back to Marx

Marx’s Alternative to the “Plain Argument”

I have shown that the conclusion that capitalists exploit workers does not follow from the “Plain Argument’s” definitions and premises. I now wish to show that the conclusion does follow from Marx’s own exploitation theory.

To facilitate comparison of the theories, I have done my best to make Marx’s theory look something like the “Plain Argument.” For simplicity, I adopt Cohen’s definitions of “workers” and “exploitation,” which are serviceable enough. By noting that capitalists make workers perform surplus labor, my argument rules out the possibility that the disproportion between what workers contribute and what they receive is non-exploitative (i.e., that workers create surplus-value to give capitalists a gift). The argument presupposes that the process of production is capitalistic and thus a value-creating process.

Marx himself expressed his theory in a rather different way, in chapters 5–7 of volume 1 of Capital, but his formulations were more complex than the ones we need if we just want to derive the conclusion that capitalists exploit workers. His own argument had to satisfy additional theoretical and polemical requirements. In particular, because it put forward an exploitation theory of profit, it had to show that capitalists exploit workers even when equal amounts of value are exchanged, and, in order to show that surplus labor is the exclusive source of profit, it had to account for the value transferred from used-up mean of production to products. Demonstrating that capitalists exploit workers without demonstrating anything more is a much simpler task, so the presentation can likewise be much simpler:

(M1) The workers’ labor helps to produce the products and it, alone, creates all of the new value they contain, the amount of which is proportional to the amount of labor performed.

(M2) During n hours of work, the workers, and they alone, create V amount of new value, equal to the amount of value they were paid as wages and benefits.

(M3) The capitalists make the workers work an additional s hours, but do not pay them anything additional.

∴ (M4) During the additional s hours, the workers’ labor helps to produce additional products and it, alone, creates the additional S amount of new value they contain.

∴ (M5) The workers contribute more value (V + S) than the amount of value (V) they received as wages and benefits.

∴ (M6) The workers are exploited.

(M7) The capitalists own/control all of the products produced, so all of the value of these products belongs to them.

∴ (M8) The additional S amount of new value that the workers created belongs to the capitalists.

∴ (M9) The capitalists receive the difference between the amount of value contributed by the workers (V + S) and the amount of value (V) that they paid the workers as wages and benefits.

∴ (M10) The capitalists exploit the workers. ■

Statement (M1) contains an empirical fact about the relation between labor and production of products, plus two of Marx’s theoretical tenets concerning the relation between labor and value creation. (M2) depends partly on (M1), insofar as it refers to labor creating value. In other respects, (M2) is an empirical claim, as is (M3).[13] (M4) is derived from (M1) and (M3). (M5) is derived by adding up the value-creation and pay information contained in (M2) through (M4). (M6) follows from (M5) and the definition of exploitation. (M7) is an empirical fact. Its second clause is implicit in its first clause. (M8) is derived from (M4) and (M7). (M9) follows from (M8) and previous steps’ definitions of V and S. (M10) follows from (M9) and the definition of exploitation.

Why does Marx’s exploitation argument succeed while the “Plain Argument” fails? They have a few things in common. Both of them say that exploitation occurs when people are made to contribute more than they receive. Both of them say that workers’ labor, and it alone, makes a certain contribution. Both of them say that workers receive less than they contribute.

But they differ with respect to what it is that workers’ labor, and it alone, contributes. Marx says that the relevant contribution here is the creation of new value. The “Plain Argument” says that the relevant contribution is the production of physical products.

One reason the “Plain Argument” fails is that workers’ labor is simply not the only thing that produces physical products. Nonlabor inputs also produce physical products, in every production process. Another reason the “Plain Argument” fails is that workers are not the only ones who contribute to the production of physical products. Nonworkers—input suppliers, lenders, entrepreneurs, governments, and so on––contribute to their production, even though they do not directly produce them. So the “Plain Argument” fails because it needs to say that only workers and their labor make a contribution to physical production, but that is patently false. To distract our attention from this basic fact, the “Plain Argument” unobtrusively substitutes “creates” for “contributes” and “he creates” for “[he] is the only person who creates.”

Marx’s argument, in contrast, is about something non-physical, the creation of new value. It therefore does not need to deny the fact that many kinds of things produce physical products, the fact that there are many kinds of contributions to physical production, or the fact that many kinds of people and other entities make contributions to physical production. Nor does it need to duck and weave to distract our attention from these basic facts. It is the real plain argument: it states plainly that workers’ labor is the exclusive source of new value. There are no obvious facts that immediately disqualify this premise. And Marx’s conclusion that capitalists exploit workers follows directly from the premise plus a few (much less controversial) empirical claims.

Compare the initial premises of the “Plain Argument” (1) and Marx’s argument (M1). While (M1) is rich with content, rich with theory, (1) is content-poor and wholly atheoretical. It is hardly surprising that a content- and theory-rich starting point can generate powerful conclusions that a content-poor and theory-deprived starting point cannot. That which Cohen, Burgis, and myriad others have regarded as a weakness of Marx’s exploitation theory, its reliance on Marx’s value theory, is in fact the key source of its strength. This is true partly because Marx’s exploitation theory relies on some value theory––unlike the “Plain Argument,” which pretends that a tautology plus the surface-level fact that products have value can together perform miracles. And it is true partly because Marx’s particular value theory is the right theory for the job, the theory that can generate the conclusion that capitalists exploit workers.

Marx vs. Burgis (and Cohen) on Justice

Cohen stated that he was “certain” that Marx held that “exploitation is unjust,” but that he would not defend this claim (Cohen, section 2), so I cannot evaluate his evidence and arguments. Burgis says that

the workers are the ones who make the products that have value. Of course, nature plays a role, but as Cohen emphasizes the worker is the only person who creates it and thus the only person who has a right to it (and by extension a right to its value). [Burgis 2019]

Thus, both Cohen and Burgis think that exploitation is unjust, that workers are the only people who have a right to the products and their value. But what does Burgis have to say about Marx’s view?