by Andrew Kliman

In response to an episode of Radio Free Humanity that discussed the so-called value-form paradigm, a listener named Albin recently posted a comment on Marxist-Humanist Initiative’s website. I was going to post a reply below his comment, but my reply became very long, mostly because there are many things in his comment that I think are wrong and need to be corrected. So I’m instead replying to Albin here, in this full-length With Sober Senses article.

I’ll quote a bit of Albin’s comment, respond to it, quote the next bit of his comment, respond, and so on. His comment also appears, in full, at the end of this article.

My understanding is that the main point of the value-form approach is to criticise physicalist conceptions of commodity production.

Yes, but the manner in which they criticize physicalist conceptions is so broad that the result is also a criticism of Marx’s—anti-physicalist but production-centered—concept of value determination. As I noted in my written critique of the value-form paradigm (p. 180), “Value-form theorists regard this [Marx’s concept] as an asocial, ‘Ricardian’ concept.” Specifically, they criticize the following aspects of his concept:

Commodities are values because they embody human labor, and the socially necessary labor-time required for a commodity’s production (which does not depend upon the price the commodity later fetches in the market) determines the magnitude of its value. … Thus commodities are values when they are produced, before and irrespective of sale. [ibid.]

Insisting that the moment of exchange actualises potential value is a way of saying that we’re only counting “social labour” [gesellschaftliche Arbeit], i.e. labour time expended for commodity society.

I think this is incorrect. Why? Because it’s possible to count only social labor without alleging that “the moment of exchange actualises potential value.” For example, Marx’s (anti-physicalist but production-centered) theory says that the amount of socially necessary labor required for a commodity’s production—which does not depend upon the price the commodity later fetches in the market—is the exclusive determinant of the magnitude of its value. And Marx’s theory says that products of labor must have use-value—which is partially socially determined—in order to have value at all.

Thus, by rejecting Marx’s value theory—according to which only social labor creates value—and saying, instead, that “the moment of exchange actualises potential value,” the value-formists are not merely affirming that only social labor counts. They are rejecting Marx’s theory that the amount of socially necessary labor required for a commodity’s production is the exclusive determinant of the magnitude of its value.

Both the use-value side and the exchange-value side of physical objects intended for sale can be regarded as useful only to potential buyers and are therefore only potential carriers of labour in general. In other words, “expenditure of human brains, nerves, and muscles” (Capital Vol. I, ch 1) does not produce value in isolation.

“Useful only to potential buyers” is incorrect. I’m not a potential buyer of a Rolls-Royce, because I can’t afford one, but if you gave me one as a gift, I’d definitely find it useful. More importantly, Albin’s formulation just seems to be a way to (intentionally or unintentionally) smuggle in the word “potential” where it doesn’t belong. Aren’t some of these physical objects useful to their actual buyers? And aren’t these objects therefore actual carriers of labor in general?

Albin is correct that “‘expenditure of human brains, nerves, and muscles’ … does not produce value in isolation.” But Marx didn’t claim that it does, nor do proponents of his value theory claim that it does. Marx’s theory says, for example, that in order to be values, products of labor must be use-values.

The value-formists say that, too. But, in contrast to Marx, they commit a crucial error here because they also claim (or imply) that no product of labor has “actual” value unless and until it is sold––because there is no demand for a product unless and until it is sold and therefore it isn’t a use-value unless and until it is sold. This claim is incorrect.

At this moment, gold is being bought and sold, at a spot price of $1,845.99 per ounce. It couldn’t be sold if there were no demand for it. Thus, at this moment, there’s demand for gold, and gold is thus a use-value.

This conclusion pertains not only to those relatively few ounces of gold that happen to be exchanging at this moment. It pertains to gold generally. If you deny this, you commit yourself to the truly bizarre position that, because you’re wearing your shoes at this moment, not exchanging them, your shoes aren’t use-values, even though they are useful to you and you are using them!

It is (barely) conceivable that, in the future, someone might not be able to sell the gold they own, because there is no longer any demand for gold. This does not negate the fact that there is demand for their gold at this moment, nor the fact that their gold is consequently a use-value and a value at this moment.

As I noted in my written critique of the value-form paradigm (p. 194, note 20), it simply means that

a product that can no longer be sold is no longer a use-value, and if it ‘loses its use-value it also loses its value’ (Marx [Capital, vol. 1, chap. 8; p. 310 of Penguin ed.]). This implies that the product did have a value originally, since a product cannot lose a value it never had. If it could have been sold when it was produced, then, according to Marx’s theory, it was at that time both a use-value and a value.

Should the seller one day find herself in a situation where only part of the output can be sold as commodities, then what happens with the remaining objects? Well, perhaps they could be stored until demand goes back up and at a later date realise part of the potential value (“hopefully valuable stuff” in the head of the producer), or maybe they can only be reused as raw materials, e.g. motor vehicles as iron and steel, where just a fraction of the potential value enters into the final product. It would then only be a fraction since that’s an inefficient way of producing such materials and society only validates the average labour time spent.

Items for which there’s no demand have neither use-value nor value. So their use as raw materials doesn’t transfer any value to the product. In any case, I don’t understand what theoretical point, if any, Albin is trying to make here, so I’ll move ahead.

The social connection happens at the moment of exchange, at the market; private producers are actualized as producers for the needs of commodity society; labour time expended becomes determined as useful (or not) in their respective quantities.

Which social connection, exactly? Not production for the purpose of exchange. That doesn’t happen at the moment of exchange. Not demand for the product, which also doesn’t happen at the moment of exchange. Not realization of social use-value, which happens only with the article’s consumption, not at the moment of exchange.

Maybe exchange? I agree that exchange happens at the moment of exchange.

As for the rest here, “private producers are actualized as producers for the needs of commodity society” if and when there’s demand for their products, which doesn’t happen at the moment of exchange. And “labour time expended becomes determined as useful (or not)” if the products are use-values, which doesn’t happen at the moment of exchange.

In fact, demand and usefulness don’t “happen” at any “moment.” They can’t be located at a specific point in the circuit of capital. They are simply attendant social conditions that aren’t part of that circuit.

To say that a product that has not yet been brought to the market already contains socially necessary value of a certain quantity confuses intended use for the actual, socially determined use and its worth seen quantitatively.

On Marx’s theory, the product already contains socially necessary labor of a certain quantity and, provided that the product is a use-value, this quantity of socially necessary labor is the exclusive determinant of the magnitude of the product’s value.

The stuff about the alleged confusion between “intended use” and “actual, socially determined use” seems irrelevant to me. No one thinks that a thing’s value or price depends on “actual, socially determined use.” Its value and price depend, in part, on whether or not the thing is useful. That’s entirely different. If I bought a dozen eggs but dropped them on the way home, and they broke, they were useful when I bought them; but they were never used. And as I noted above, “actual, socially determined use” has nothing to do with the moment of exchange, because the consumption (i.e., use) of a commodity, which is the realization of its use-value, takes place only after it has been bought, not at the moment of exchange.

On the contrary, those who intend to be sellers of commodities must enter into exchange with one another; they “create society” by presenting their objects as commodities, expecting that they be recognised as such.

Sellers enter into exchange with buyers––but whatever.

I don’t know what “create society” means. It might mean that Albin is claiming that the act of exchange is what turns non-commodities (or “potential” commodities) into commodities. I think that’s simply wrong. An ounce of gold that is not being bought and sold at this moment is a commodity. It’s a use-value and a value. Purchase of the ounce of gold doesn’t take a non-use-value (or a “potential” use-value) and turn it into a use-value. Why not? Because, again, usefulness isn’t something that “happens” at any “moment.”

What Albin might be wanting to say is that potential sellers don’t know whether the products of labor that they hope to sell are use-values; and thus they don’t know whether these products are values and commodities. And they don’t know what the magnitudes of products’ prices and values are. They acquire this information at the moment of exchange (or non-exchange, if they’re not able to sell the products).

That’s all completely correct. But it has nothing whatever to do with the determination of the magnitudes of the products’ prices and values, and nothing whatever to do with whether the products are use-values. As I keep stressing in the Radio Free Humanity podcast episodes on the value-form paradigm, there’s a crucial difference between epistemic and ontological issues—i.e., between what is known and what is. And things don’t first need to be known before they can come into being (i.e., can exist). If one denies this last point, one is committed to the view that Neptune wasn’t a planet in our solar system before September 23, 1846––or that it was only a “potential” planet before that date.

Albin’s comment concludes with a longish quote from Marx that doesn’t at all do what he wants it to do and needs it to do. That’s because the passage from Marx is about how exchange affects what producers know, because it makes certain relations apparent to them. “[T]he specific social character of each producer’s labour does not show itself except in the act of exchange,” and “the labour of the individual asserts itself as a part of the labour of society” only though exchange. However, the passage does not say that the act of exchange brings these relations into being. In fact, it implies the opposite, since something can “show itself” and “assert itself” only if it already exists, independently of the showing and asserting.

The last sentence that Albin quotes seems to be an exception to this; it does seem to suggest that the purchase and sale of the products is what brings their values into being (i.e., what makes them values) . But that’s only because of the peculiar manner in which Albin truncated the quoted material.

The last sentence is: “It is only by being exchanged that the products of labour acquire, as values, one uniform social status, distinct from their varied forms of existence as objects of utility.” In the Penguin edition of Capital, this sentence is the start of a new paragraph. In any case, the sentence is not about the act of exchange, which would have been apparent if the passage hadn’t been hadn’t truncated at this point. What Marx wrote is

It is only by being exchanged that the products of labour acquire, as values, one uniform social status, distinct from their varied forms of existence as objects of utility. This division of a product into a useful thing and a value becomes practically important, only when exchange has acquired such an extension that useful articles are produced for the purpose of being exchanged, and their character as values has therefore to be taken into account, beforehand, during production. From this moment the labour of the individual producer acquires socially a two-fold character.

To understand why this isn’t about the act of exchange, let me quote myself once more:

the … production-centered concept of value determination does contain elements of the determination of value ‘in exchange’––where exchange refers to ‘a social form of the process of reproduction.’ However, this sense of ‘exchange’ is not the relevant one here. The difference between the [production-centered] concept of value determination … and the typical value-form concept turns on whether the magnitude of value depends upon exchange in the sense of ‘a particular phase of th[e] process of reproduction, alternating with the phase of direct production’ (i.e. the sale of an article subsequent to its production).

This distinction between the two senses of exchange, well known to value-form theorists, was made by I. I. Rubin (1973, 149), whose formulations I have quoted. [p. 184 and p. 184, note 9] END

All of the epistemic stuff––“show,” “asserts”––is about what Rubin referred to as “a particular phase of th[e] process of reproduction, alternating with the phase of direct production,” namely the act of exchange that follows production. But the continuation of the paragraph is not about the act of exchange. Instead, it’s about the other sense of “exchange”–– which Rubin referred to as a “social form of the process of reproduction”; in other words, it’s about a particular historical epoch in which exchange relations are dominant.

Consequently, the sentence in question does not say or imply that products of labor acquire their values when they are sold. It says that they acquire their values within this historical epoch, because now the products are produced for the purpose of being exchanged, and this new purpose affects their production “beforehand”––before they are sold and whether or not they are sold. “[D]uring production,” the individual producer’s labor has a “two-fold character.” It is concrete labor and it is abstract labor—already in the process of production, prior to the product being sold. And in Marx’s theory, abstract labor is what creates value. Hence, in his theory, value is created in production, prior to the product being sold.

When I say that “value is created in production,” I mean actual value, not just so-called “potential” value. If and when a commodity is sold, the sale doesn’t “actualize” its value––I have never, ever, seen anywhere where Marx said such a thing. As I noted in my written critique of the value-form paradigm,

Marx did speak of the ‘realization’ of commodities’ prices in circulation, but the term he used was Realisierung, not Verwirklichung (actualization). Realisierung is German for “realization” in the ordinary accounting sense. A capital gain, for example, “accrues” to the owner of an asset when its price rises (i.e., s/he becomes wealthier), while this already existing capital gain is “realized” when the asset is sold at this higher price. [p. 180, note 4]

The expression “potential value” just seems to serve the purpose of denying that labor creates value while appearing not to deny it. Use of that expression allows one to avoid making a clear statement that amounts to the same thing, but which reveals rather than hides the fact that it contradicts Marx’s theory. For example, here is a clear statement of the true import of the phrase “potential value”:

workers’ labor produces material objects but does not create value. These material objects have the potential to be values, but unless and until the objects are sold, this potential is unrealized; they do not have value. Thus, the objects acquire their values exclusively in the market, by being sold.

This, of course, is precisely what mainstream bourgeois economics says.

Finally, let me say that I have problems with the way in which Albin has thus far debated what Marx’s theory of value determination was. Albin provides his interpretations and one cherry-picked quotation. One problem I have with this procedure is that it forces me to refute things that I think I have already refuted, again and again—in the paper I’ve linked to here, in the Radio Free Humanity podcasts, and elsewhere. It would be better to first internalize the responses to value-formist arguments, and then focus just on new or unresolved points, instead of making us relitigate stuff that should have been put to rest long ago.

Yet my bigger problem with the procedure is that it is one-sided. It tests the value-form interpretation of Marx by means of evidence that initially seems to confirm it. Albin’s comment just consists of such potentially confirmatory evidence, plus some value-formist arguments. No consideration is given to textual evidence that disconfirms the value-form interpretation, in the eyes of its critics, or to their counterarguments. This one-sidedness is especially problematic because it sets the bar far too low. It subjects the value-form interpretation to only the weakest kind of test. After all, it is always easy to produce evidence and arguments that seem to confirm something. It is much, much harder to overcome evidence and arguments that seem to disconfirm it.

In the present case, I think the evidence that disconfirms the value-form interpretation of Marx most decisively is the whole second half of my written critique of the value-form paradigm. It shows that the value-form position, according to which commodities acquire their (“actual”) values through the act of exchange, at the moment they are exchanged, is incompatible with three of Marx’s theoretical contributions:

(a) his theory that surplus-value cannot arise in circulation, and therefore his theory that the exploitation of workers is the exclusive source of profit,

(b) his critique of the quantity theory of money, the forerunner of modern monetarism,

and

(c) his theorization of what is now known as intra-firm trade, in which firms’ outputs become their own inputs without passing through the market.

Patrick Murray responded to these demonstrations, first in his written response to my critique, and, more recently, in a Radio Free Humanity episode. But I don’t think it can seriously be argued that he succeeded in showing that the value-form position is actually compatible with these aspects of Marx’s value theory. And no one else has even tried, as far as I know. I invite Albin to try. Indeed, all supporters of the view that Marx himself was a value-formist (in the modern, market-centric sense) are invited to try. “These are the conditions of the problem. Hic Rhodus, hic salta!”

November 30, 2020 at 1:44 pm

My understanding is that the main point of the value-form approach is to criticise physicalist conceptions of commodity production. Insisting that the moment of exchange actualises potential value is a way of saying that we’re only counting “social labour” [gesellschaftliche Arbeit], i.e. labour time expended for commodity society. Both the use-value side and the exchange-value side of physical objects intended for sale can be regarded as useful only to potential buyers and are therefore only potential carriers of labour in general. In other words, “expenditure of human brains, nerves, and muscles” (Capital Vol. I, ch 1) does not produce value in isolation.

Should the seller one day find herself in a situation where only part of the output can be sold as commodities, then what happens with the remaining objects? Well, perhaps they could be stored until demand goes back up and at a later date realise part of the potential value (“hopefully valuable stuff” in the head of the producer), or maybe they can only be reused as raw materials, e.g. motor vehicles as iron and steel, where just a fraction of the potential value enters into the final product. It would then only be a fraction since that’s an inefficient way of producing such materials and society only validates the average labour time spent.

The social connection happens at the moment of exchange, at the market; private producers are actualized as producers for the needs of commodity society; labour time expended becomes determined as useful (or not) in their respective quantities.

To say that a product that has not yet been brought to the market already contains socially necessary value of a certain quantity confuses intended use for the actual, socially determined use and its worth seen quantitatively. That is not to say that exchange or supply and demand enter into the equation from the outside. On the contrary, those who intend to be sellers of commodities must enter into exchange with one another; they “create society” by presenting their objects as commodities, expecting that they be recognised as such.

“As a general rule, articles of utility become commodities, only because they are products of the labour of private individuals or groups of individuals who carry on their work independently of each other. The sum total of the labour of all these private individuals forms the aggregate labour of society. Since the producers do not come into social contact with each other until they exchange their products, the specific social character of each producer’s labour does not show itself except in the act of exchange. In other words, the labour of the individual asserts itself as a part of the labour of society, only by means of the relations which the act of exchange establishes directly between the products, and indirectly, through them, between the producers. To the latter, therefore, the relations connecting the labour of one individual with that of the rest appear, not as direct social relations between individuals at work, but as what they really are, material relations between persons and social relations between things. It is only by being exchanged that the products of labour acquire, as values, one uniform social status, distinct from their varied forms of existence as objects of utility.” (Capital I, 1867 ed., ch 1, SECTION 4 THE FETISHISM OF COMMODITIES AND THE SECRET THEREOF, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch01.htm#S4)

Again and again I have to battle with one of the issues discussed here, and which has been discussed many times before. Andrew Kliman writes:

“… and things don’t first need to be known before they can come into being (i.e., can exist).”

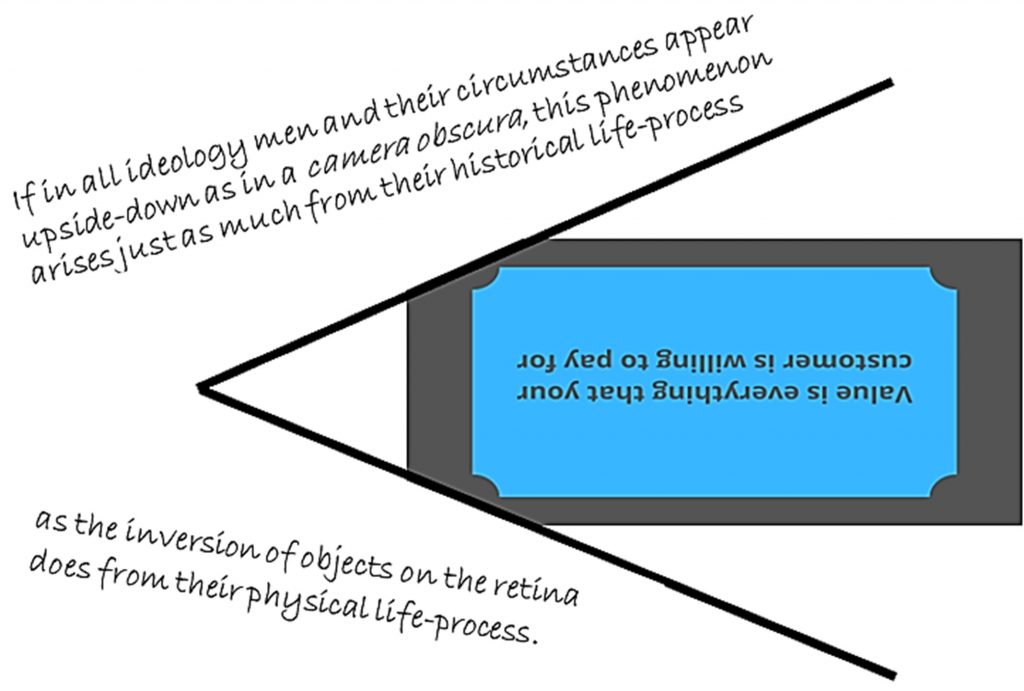

This argument is a red rug to a bull to many mainstream scholars and they might accuse one of committing an epistemological error. To them, the idea that value exists only when someone is willing to pay for it — meaning that the thing sells — is a commandment. Suggesting otherwise is blasphemy.

And they go further, conflating value as a concept with the magnitude of value. This is apparent in their assertion that “value equals willingness to pay a certain price”. Again a commandment.

This is the legacy of Austrian economics, which, in my view is so pervasive that it underlies all mainstream thinking in management and economics. And in my opinion it underlies value-form thinking. I see it as an attempt to “reconcile” Austrian thinking with Marx. But when value-formists find out that their attempt breaks Marx, they accuse him of having been broken all along. That’s not scholarly. They should instead ditch Menger and Böhm-Bawerk, or keep them away from Marx. That would be the scholarly thing to do.

Yes, they assume individualism and insert it in their version of Marx. That is the most basic error they make.