‘It was a popular revolt, not an anti-immigrant vote’: Left Brexiteers evade the charge of condoning racism

by Chris Gilligan, author of Northern Ireland and the crisis of anti-racism

The majority vote to leave the European Union (EU) has been celebrated by many on the Left (Lexiteers) as a revolt by the ‘left-behind’ working-class. The same vote has been condemned as enabling substantial racism and anti-immigrant sentiments. This article critically examines various Left attempts to defend the ‘Leave’ vote against the accusation of racism. According to these defences, a vote to leave the EU was in the interests of the working class, or of human liberation more broadly. The article highlights some contradictions between the goal of human emancipation and the defence of the Leave vote against the accusation of racism.

Introduction

In June 2016, a majority of voters in the UK voted to leave the EU. The issue of the EU referendum has been a divisive one for the Left, both during the referendum campaign and in the aftermath of the vote. Many people on the Left supported a Remain (in the EU) position. Some advocated Leave (or Brexit, i.e., Britain exiting the EU). Marxist-Humanist Initiative (MHI) did not take an official position, for or against, Leave or Remain. Instead it facilitated a discussion by publishing an article which expressed support for Remain, and one that argued for not taking sides. MHI also carried two articles by me that likewise argued for not supporting either side. Left-wing supporters of Leave (Lexiteers) were delighted at the referendum result. They have argued that the vote was a revolt by the ‘left behind’ working class, kicking back against a ruling class that has either ignored them or maligned them.

The Leave campaign, and the Brexit result, have been condemned as racist, because of the centrality of anti-immigration sentiment to the Leave vote. The charge of racism is a serious accusation to level at anyone who claims to be committed to the struggle for human emancipation. Defenders of the Leave vote have replied to the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument in three main ways. The most common form of defence against the criticism of racism has been to evade the criticism.

In contrast to this dominant response, there have been two different arguments that attempt to engage with, and argue against (rather than evade) the accusation of racism. One argument involves acknowledging that racism was a feature of the Brexit vote, but claims that we need to make a distinction between hard-core racists and other Brexit voters. In this argument, the racism of a hard-core minority is contrasted to the genuine concerns about immigration expressed by the majority of Brexit voters. In this article, I will examine this response to the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument through a critique of its articulation by David Goodhart.

The second serious attempt to defend the Leave vote from accusations of racism is the argument that the anti-immigrant sentiment was an expression of something else—a desire for national sovereignty. In this second argument, the immigration issue is said to have provided a focus for anti-EU sentiment, because it crystallised the more substantial issue of the EU’s undermining of UK sovereignty. This defence is based on the claim that the Brexit vote was not an expression of racism, but rather, was an expression of a desire to hold UK politicians to account. In this article, I examine this defence, through a critique of its articulation by Chris Bickerton and Richard Tuck.

The present article takes at face value the claim that those defending the Leave vote from the accusation of racism have the best interests of the working-class at heart. It takes as its starting premise the idea that the emancipation of the working-class from capitalist domination is a goal worth striving for.

This article, however, differs from most (perhaps all) Lexiteers in assuming that the working-class needs to be the author of its own liberation; no-one else can do the task for them. It uses the goal of human liberation, through the self-emancipation of the working-class and oppressed peoples, as the criterion against which to judge the various defences of the Leave vote from the accusation of racism.

The article is divided into four main parts. The first part points to the ample evidence that anti-immigrant sentiment was a significant factor in the Leave campaign and vote. (This part also provides a substantiation of the assertion, in the MHI document Resisting Trumpist Reaction (and Left Accommodation), that: ‘In the UK, the surge of support for Brexit last year, which secured the victory of the “Leave” forces, was driven largely by anti-immigration backlash’ (p. 49).) The second part outlines a number of different attempts to evade the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument. The third part provides a critique of Goodhart’s defence of Brexit voters from the accusation of racism. The fourth part does the same for Bickerton and Tuck. The article concludes by noting the importance of challenging racism as part of the broader struggle for human emancipation.

Anti-immigrant sentiment and the Leave vote

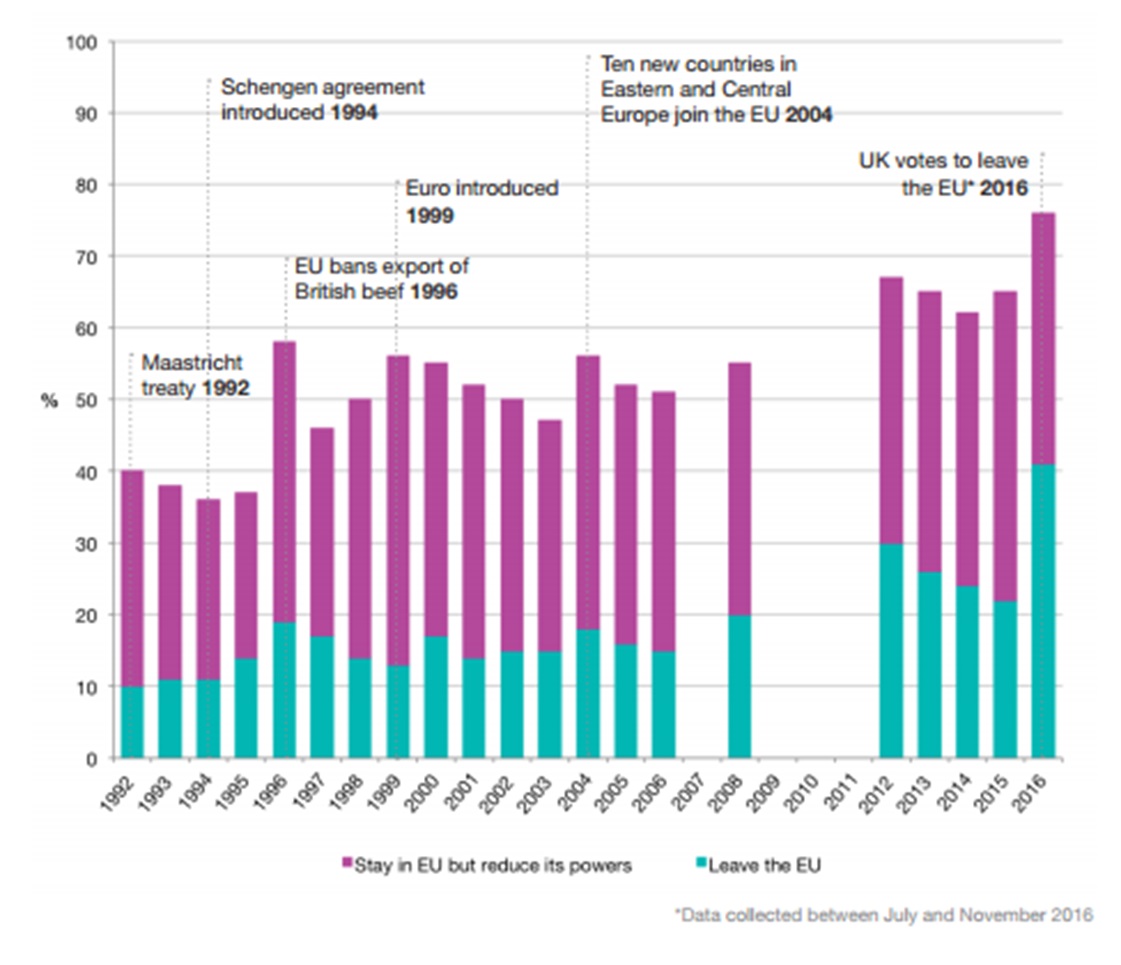

Several polls, conducted before the referendum, highlighted immigration as a key issue. A study by two academics, Geoffrey Evans and Jonathan Mellon, for example, found a strong link between concern about immigration and a negative view of the EU. They also pointed out that the negative view of the EU had ‘strengthened considerably in the years following the opening of access to immigrants from the 2004 accession countries’ (i.e. those countries, mainly East European, that joined the EU in 2004). They also pointed to a 2015 poll that showed that ‘only 10% of people who do not believe too many immigrants have been let into the country would vote to leave the EU. But no less than 50% of those who believe too many immigrants have been let into the country would do so’. In other words, people who were unconcerned about immigration numbers were very unlikely to vote Leave. On the other hand, half of those who were concerned about immigration numbers were likely to vote Leave. Pro-immigration sentiment was clearly on the Remain side, and anti-immigration sentiment equally divided between the two sides.

A YouGov survey, conducted in the summer of 2015, found that the core support for leaving the EU (23%) and for remaining (31%) was insufficient to clinch the vote. They also found that 17% intended to vote to leave, but were open to persuasion, while 19% intended to vote to remain, but were open to persuasion. And 10% were completely undecided. The survey also found that amongst both the core and ‘soft’ (i.e. open to persuasion) Leave voters ‘the arguments seen as most convincing were those around immigration and money currently spent on EU membership being better spent on services in Britain’. And, notably for the Leave campaign, these ‘were also the arguments seen as most convincing by soft REMAIN voters’ (emphasis in the original). Concern about immigration, therefore, was an issue that the Leave campaign could potentially exploit as a means to swing soft Remain voters onto their side in the referendum vote.

Another 2015 study, by Lord Ashcroft, employed focus groups in order to probe the reasoning behind public opinion regarding the forthcoming referendum. This study predicted that immigration would become ‘central to the debate, since it touches many of the broader themes behind the debate, including prosperity, security and identity’. Polling conducted as part of the same study suggested that an overwhelming majority of those polled wanted to control the numbers of immigrants coming to the UK. Almost 40% of those polled thought ‘we’ll never be able to bring immigration under control unless we leave the EU’. But almost as many thought that ‘we won’t be able to bring immigration under control even if we leave the EU’ (emphasis in the original).

The official, and unofficial, Leave campaigns consciously sought to harness anti-immigrant sentiment in their attempts to clinch a Brexit vote. As a report in the Washington Post noted:

In the run up to the E.U. referendum, the official ‘leave’ campaign initially tried to focus on sovereignty and economic issues. However, polls clearly showed that immigration was one of the most, if not the most, important factors for voters. ‘Immigration is by far the best issue for the “Leave” campaign,’ Freddie Sayers, editor in chief of the polling firm YouGov, wrote. ‘If the coming referendum were only a decision on immigration, the Leave campaign would win by a landslide.

Hostility to immigration became central to the Leave campaign. The official Leave ‘Let’s Take Back Control’ campaign highlighted five points—two of these were about immigration or immigrants. They claimed that a Leave vote would give the UK control over ‘our’ borders by allowing ‘us’ to create ‘a new points-based immigration system’ and it would enable ‘us’ to control ‘our’ security by allowing the UK to ‘deport dangerous foreign criminals’.

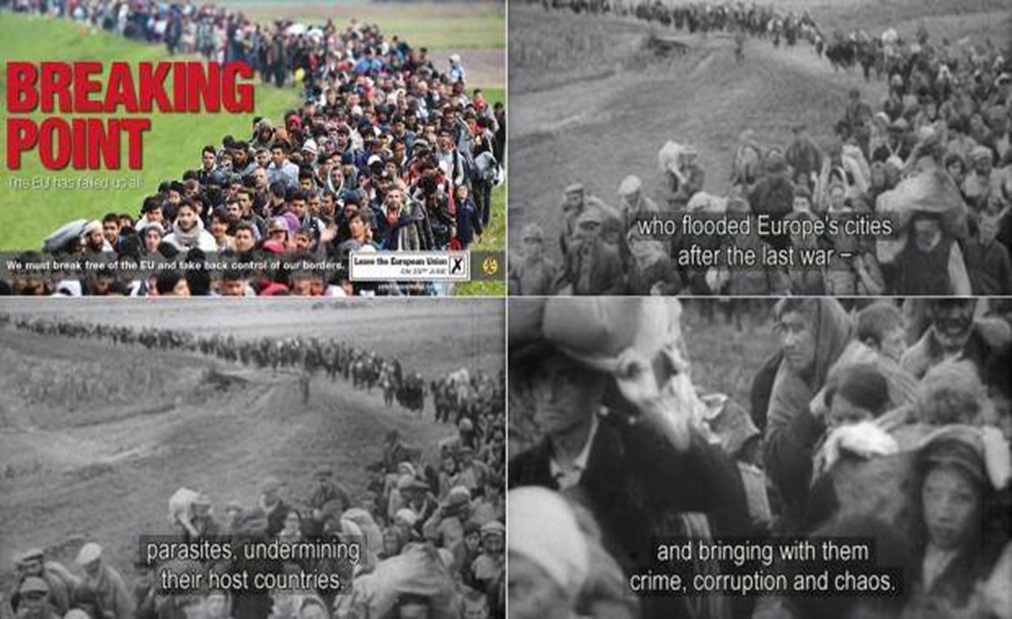

Immigration was also central to the UK Independence Party’s (UKIP) campaign in the referendum. The most notorious expression of its centrality was UKIP’s ‘Breaking Point’ poster, which has been compared to Nazi anti-refugee propaganda. This poster was considered so toxic that even prominent Leave campaigners sought to distance themselves from it.

The official Remain campaign was not pro-immigration. The EU’s rules on free movement for EU citizens within the EU, however, meant that the campaign’s attempts to reassure the electorate on the immigration issue were unconvincing. The Stronger In (the EU) website, for example, sought to reassure voters by saying that Norway and Switzerland, which are not part of the EU, still have to accept free movement for EU citizens. They further claimed that the UK did have control over its borders: firstly, because the UK is outside of the EU’s Schengen passport-free zone, and secondly, because ‘cooperation with France allows us to manage illegal immigration’ and such cooperation might not be forthcoming if the UK were to leave the EU.[1] David Cameron, the pro-Remain Prime Minister, attempted to cut the legs from under the Leave campaign’s use of the immigration issue by securing a deal with the EU to restrict welfare benefits available to EU migrants in the UK. Restricting benefits, however, is not the same as restricting immigration.

Studies conducted after the referendum confirm that immigration control was a crucial issue. A poll conducted on the day of the vote, for example, found that a third of Leave voters who were polled (33%) said that the main reason for their vote was that leaving ‘offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders.’ An analysis of data from the British Election Study survey of referendum voters concluded that the data suggested ‘that the decision taken by the Leave campaigns to focus heavily on the immigration issue … helped to drive public support for leaving the EU while also complicating the ability of Remain campaigners to “cut through” and galvanise support for continuing EU membership’. A study of the British Social Attitudes survey used the data to test two popular explanations for the Brexit vote: firstly, that it reflected ‘the concerns of more “authoritarian”, socially conservative voters about the social consequences of EU membership—and especially about immigration’; and secondly, ‘that the vote was occasioned by general public disenchantment with politics’ (a version of the ‘revolt against the elite explanation’). The study found that the survey data provided more evidence to support the first explanation than it did to support the public-disenchantment one.

So, immigration control was a key feature of the Leave vote. Not only was immigration a key feature of the campaign, but both the official Leave campaign and the UKIP campaign invoked the topic of immigration in nationalistic, or nativist, terms—‘our’ jobs, ‘our’ welfare, ‘our’ borders. There is thus ample evidence to support the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument, and to substantiate the MHI assertion that the Brexit vote was largely driven by anti-immigrant backlash.

What’s racism got to do with it?

There have been various attempts by Lexiteers to evade the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument. Some have outright denied that hostility to immigration was a factor in the Leave vote. Some have attempted to neutralise the accusation of racism by pointing to ways in which the EU is anti-immigration. Some have tried to shift the terms of the discussion by saying that racism predates the referendum campaign, so racism therefore cannot be responsible for the Leave vote. Others have attempted to turn the argument around by saying that the real prejudice in the campaign is the anti-working-class prejudice of whining Remain voters (a new term, Remoaners, has been coined to disparaged people who have criticised the Leave vote). In this section, we shall critically examine some of the attempts by Lexiteers to evade the accusation of racism.

I have had some most-bizarre Facebook exchanges with Lexiteers who flatly denied that the Brexit vote had anything to do with immigration. These exchanges were frustrating encounters with a post-truth universe. In one exchange, for example, I was told that there was nothing on the ballot paper about immigration; all that was mentioned were the options ‘Leave the EU’ and ‘Remain in the EU’. Therefore, I was told, the vote could not have been about immigration. I responded to this evasion by saying that people must have had a reason to vote Leave; there must have been something about the EU that they objected to. I then pointed to the evidence from polls (cited above), which showed that immigration was one of the main reasons given by voters for choosing Leave. In response I was accused of being a sore loser and told again that there was nothing on the ballot paper about immigration.

Such responses, which held firm to an idea and refused to engage with available data, involve a refusal to test the claims being made. Denying that a desire to control immigration was a central element in the Leave vote involves denying reality. The goal of human liberation requires engaging with the world as it actually is, not as we would like it to be. If we cannot even acknowledge the existence of hostility to immigration amongst sections of the working class, then we are complicit in this hostility.

Other Lexiteers, who have tried to evade the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ argument, at least acknowledge that anti-immigration sentiment was a feature of the Leave campaign. The evasion lies in their attempts to try to downplay its significance in some way. Lee Jones, for example, points out that EU immigration controls have been responsible for the death of thousands of migrants who have drowned while attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea from Turkey. Therefore, he argues, voting Leave is consistent with being anti-racist.

There is a basis to Jones’s argument. The EU treats labour-power as a commodity, which, like all commodities within the EU’s common market, can circulate freely. Movement into the EU from outside its borders, however, is a different matter. The pressure points of the ‘migration crisis’ in Europe are at the borders of the EU, precisely because this border is not open. The fact that the EU operates racist immigration controls is not, however, an argument in favour of Leave. The UK currently operates racist immigration controls, and did so before it joined the EU. Any Remain voter who supports a racist EU, while at the same time condemning Leave voters for being racist, is being hypocritical. By the same token, anyone who acts as an apologist for the racism of Leave voters, but also condemns the EU for being racist is being inconsistent. There is, however, no contradiction involved in opposing both the racist immigration policies of EU border controls and the racism of the Leave campaign. The logic of the ‘EU is racist’ argument, when it does not ignore the racism involved in the Leave vote, should lead us to reject the referendum, on the grounds that the Leave/Remain choice represents a false dichotomy.

Another evasive argument is the claim that racism pre-existed the referendum campaign, it was not created by the campaign, therefore the campaign did not cause racism. It is true that racism pre-existed the referendum campaign. The referendum campaign did, however, turn up the heat on the immigration debate. There was a spike in recorded racist incidents in the weeks following the referendum vote in June 2016. Luke Gittos, for example, says of this surge in recorded incidents that: ‘We should investigate each incident and prosecute where necessary …. But we must also approach these hate-crime claims critically, given that there are plenty of Remainers who are willing to exploit any perceived spike’. Gittos is suggesting that racial incidents are an unfortunate fact of life that needs to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, rather than being integral to capitalism as a social system. His concern is not with ending racism, but with defending the outcome of the referendum vote.

A third evasive argument involves the claim that the issue of racism was being used by political elites to pour scorn on working-class Leave voters in an attempt to delegitimise the Leave vote. It is also true that some Remain supporters have used scare tactics and hyperbole. The Leave campaign has been accused of creating a political atmosphere reminiscent of pre-Nazi Weimar Germany. Remain supporters do not, however, have a monopoly on smear and insult as a substitute for reasoned debate. Both sides of the referendum debate have been dominated by appeals to emotion over reasoned argument.[2] Flat denial of the racism charge, the mirror image of the ‘it-was-racism-that-won-it’ accusation, is dismissive of the concerns of those Remain supporters who point to evidence that racism was a key feature of the Leave side’s vote.

There was a surge in recorded racist incidents in the wake of the referendum. A significant number of voters did cite opposition to ‘uncontrolled’ immigration as a motivation for voting Leave. (Remain voters who opposed ‘uncontrolled’ immigration did not cite this as motivation for voting to remain in the EU). Nativist arguments—that immigrants are ‘taking our jobs and our benefits’—were a prominent feature of the Leave campaign.

Each of the arguments presented in this section evade the issue of racism in some way. They do not take seriously the concerns of people who point to racism in the referendum campaign, nor do they take seriously concerns about what the hostility to immigration will mean for life in the UK after Brexit. The working class cannot emancipate themselves if they are willing to look the other way when racism rears its ugly head.

The inflation of racism?

David Goodhart has also questioned the significance of racism to the Leave vote.[3] His best-selling book, The Road to Somewhere, was widely praised for capturing the mood of the moment. Goodhart argues that the two major political upheavals of 2016—the Brexit referendum vote and the election of Donald Trump as the US President—starkly reveals a fundamental cultural divide in modern liberal-democratic societies. He also suggests that this divide, between what he calls the Anywheres and the Somewheres, can also be seen in the electoral growth of right-wing populist parties in Europe.

In his dichotomous view of society, the Anywheres are highly educated and mobile. They are at home in a globalised, morally liberal world. They voted Remain in the referendum. The Somewheres ‘are more rooted and less well educated … [they] value security and familiarity and are more connected to group identities’.[4] And they overwhelmingly voted Leave. Goodhart’s worries that the Anywheres, who are a demographic minority but dominate politics and social and cultural life, are indifferent to the concerns of the Somewheres, who are a demographic majority but lack political, social or cultural influence. Goodhart’s book is a plea for the Anywheres to take seriously the concerns of the Somewheres.

The issues of immigration and racism are central to Goodhart’s argument. He acknowledges that a significant minority of those who voted Leave (approximately 5 to 7% of the population) are bigots who are opposed to immigration, take a hard line on law and order issues, are ‘very prejudiced against people of other races’, believe that ‘equal opportunities have gone “much too far” for black and Asian people’ and would mind a lot if a close relative married a Muslim person (pp. 44-45). Goodhart is keen, however, to distinguish those bigots from the vast majority of Leave voters, and many Remain voters, who oppose immigration, are nostalgic about the past and have ‘a more “fellow citizens first” view of national identity’ (p. 45).

In an article for the journal Political Quarterly (PQ), Goodhart has argued that it is important to make a clear distinction between racist bigots and the majority who hold ‘perfectly normal human feelings … like wariness of strangers or allegiance to the group among which one has been brought up’. He is concerned that a clear political distinction needs to be made between the minority of bigots and the majority of moderate nationalistic-minded people. If this distinction is not made, he suggests, there is a danger that politics in the UK will be, and to some extent already has been, dominated by a yawning political and social dividing line, with liberal Anywheres on one side, and nostalgic, nationalist, Somewheres on the other.

In the PQ article, he argues that the majority of the population of the UK are not racist. Racism, he says, ‘is either literally illegal or at least illegitimate in British society …. Racial equality is part of the common sense of British society’ (p. 253). Goodhart claims that despite the fact that anti-racism enjoys mainstream acceptance, British opinion appears to be obsessed with racism. In part, he says, this is because ‘as the ethnic minority population grows, so issues surrounding race and racial justice loom larger in public life’ (p. 253). In this regard the higher profile of ‘racial’ issues is an indication of moves by ethnic minorities to become integrated into British society. However, this integration of ethnic minorities, Goodhart complains, is undermined by attempts to use the issue of racism ‘to intimidate––to police political debate and exclude some people from it’ (p. 253). This politicised use of ‘racism’, he suggests, reinforces the sense of alienation and powerlessness of the ‘white working class’.

The following quote, from a ‘white working-class’ woman from Barking, illustrates what Goodhart means: ‘I think that anti-racists have made it worse. They look for trouble. They construe everything as racist …. These people are ruining our country. And we’re the only ones who can be racist’. Goodhart knows how she feels. In the Road to Somewhere, he says that in 2004 he ‘raised questions about the conflict between rapidly increasing ethnic diversity and the feelings of trust and solidarity required to sustain a generous welfare state’ (p. 13). When he did so, those in the liberal Anywhere circles that he frequents accused him ‘of “nice racism” and “liberal Powellism”’ (p. 14).[5]

Goodhart’s criticism of anti-racism is not as radical, or pro-working-class, as he would have us believe. It is entirely consistent with the official anti-racism of UK ‘race relations’ policy. The development of official anti-racism in the UK in the 1960s went hand-in-hand with racist immigration controls. The rationale was that laws prohibiting racial discrimination and incitement to racial hatred were required to help facilitate the integration of immigrants from the Caribbean, India and Pakistan. This integration, however, was viewed as impossible without laws to control the number of immigrants coming from the New Commonwealth (i.e. former colonies with a majority Black population). The underlying concern was with maintaining social stability. This concern with social stability and immigrant integration re-emerged as a prominent concern amongst the British political class at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It can be seen in the concerns about ‘community cohesion’. Such concerns were popularised by two formers head of the Commission for Racial Equality, when they claimed that the UK was ‘sleepwalking’ into racial segregation.

Official anti-racism in the UK is not about eradicating racism; it is about managing relations between different ‘racial’ groups. Official anti-racism takes racial difference as given. Goodhart’s argument is that ‘race relations’ policy has swung too far towards favouring immigrants over the ‘white working class’ or, perhaps more accurately, that it has given too much power to anti-racist campaigners. To more effectively manage race relations, Goodhart is suggesting, policy needs to be recalibrated towards addressing the concerns of the settled (Somewhere) population regarding immigration and their sensitivities regarding accusations of being racist.

Goodhart’s vision is anathema to working-class emancipation. In talking about the ‘white working class’ he is denying the reality that the UK working class is multi-ethnic. He is ignoring the role of immigrants in the struggle for better living and working conditions, and for political rights. From the Chartist movement for civil and political rights in the nineteenth century through successful industrial action against the ‘gig’ economy today, immigrants and ethnic minority ‘outsiders’ have played important roles in the fight for working-class emancipation.[6]

Goodhart’s analysis locates the problem in human nature. It is natural, he argues, to want to stick with and look after your ‘own kind’. He argues for restricting immigration so that UK workers get a larger share of society’s resources––jobs, welfare, housing etc. The logic of his argument is that fellow nationals, regardless of whether they are bosses or workers, are our ‘own kind’, and that fellow workers, regardless of nationality, are not. Goodhart might object and say that he recognises that there are antagonisms between bosses and workers, but inasmuch as that antagonism leads to workers calling on their bosses to give preferences to ‘native’ workers, they are on the side of employers, not fellow workers.

In focusing on immigration as the source of problems, Goodhart also gets the relationship between immigration and employment the wrong way around. Bickerton and Tuck point out that the ‘UK economy relies on an expansion of the labour market for growth … [which] makes the UK economy structurally dependent upon high levels of net migration’ (p. 37). In the Great Recession, after the financial crash of 2008, unemployment levels rose across Europe. It is notable that employment levels in the UK, with its relatively open and unregulated labour market, bounced back very quickly when compared to other European countries. Most of this job growth, however, was in the low-wage economy. As Steve Coulter points out, this is a structural phenomenon, not one created by immigrants.

The hardships, the sense of being ‘left behind’, and the sense that ‘we don’t exist to them’––which led many in the working class to ‘revolt against the elite’ by voting Leave––were not created by immigrants. They are created by a capitalist system that is not within the control of any government, and by austerity policy, which is a conscious choice of government.

Marx recognised that anti-immigrant sentiment was used by the ruling class to divide and rule the working class. In an 1870 letter to fellow members of the International Workingmen’s Association, he argued that the antagonism between Irish immigrants and English workers

is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling-classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.

Today, anti-immigrant antagonism is as central to understanding the impotence of the British working-class as it was in Marx’s day. Emancipation from the influence of capitalist ideology is a necessary step in the struggle for the self-emancipation of the working-class.

Immigration controls, yes. Racist, no?

Chris Bickerton and Richard Tuck, in their defence of Brexit and the Brexit vote, are upfront in their acknowledgement of the central role that the issue of immigration played in the Leave vote. They argue that

when the British [public] were told for the first time that whomever they voted into Parliament, nothing significant could be done about EU immigration unless Britain left the EU, they suddenly realized that the basic political structures in which they lived had been transformed, and that there was literally nothing they could do about it… Though fear of this [political exclusion] was inevitably intertwined with hostility to immigration, the fact of powerlessness was real (p. 9).

Bickerton and Tuck argue that immigration was a central issue in the Leave campaign, not because the public is racist, but because the voting public was concerned that membership of the EU rendered their government impotent. The immigration issue, they argue, was the most concrete example of the powerlessness of politicians to make decisions in the UK, for policies that affected the UK. As long as the UK remained in the EU, the country has to accept the free movement of any EU citizen who wants to come and live and work in the UK. The Leave vote, Bickerton and Tuck argue, ‘is therefore above all about sovereignty’.

In their view, the pro-Leave slogan which had most resonance with the public––‘take back control’ ––expressed the popular desire to be able to hold politicians and government accountable. They argue that the EU is unaccountable to the public. For example, the EU ‘empowers national executives, not domestic publics. At every step of EU policymaking … decision-making is kept well away from any direct consultation with domestic publics’ (p. 10). Central to Bickerton and Tuck’s argument in favour of Leave is the claim that exiting the EU will remove crucial mechanisms, EU collective decision-making and EU law, through which UK government was able to evade public accountability. Brexit, they argue, is about popular sovereignty. It is about ‘self-government and political autonomy’ (p. 10). The people should rule, through their elected representatives, and state functionaries should implement the will of the people.

So, Bickerton and Tuck argue that the immigration issue was one which most clearly crystallised the issue of sovereignty. A country which does not have any say over immigration controls, they suggest, is not a sovereign state. Conversely, if the UK is to be a sovereign state then they must have control over immigration policy. Bickerton and Tuck also argue against the idea that the centrality of the immigration issue to the Leave vote means that the vote was necessarily racist, by arguing that immigration controls are not necessarily racist. They propose that the UK government should offer those EU nationals who have a National Insurance Number, and who were living in the UK at the time of the referendum, easy access to UK citizenship. This, they say, would make ‘it clear that there is nothing nativist or chauvinist about the decision to leave the EU’ and would grant those who took this offer full UK citizenship rights (p. 34).

It is true that the motivation behind the call for immigration controls is not necessarily racist. There are a whole number of reasons why people might want to restrict immigration. A post-referendum opinion poll study by the UK branch of the think tank Open Europe, for example, found that whether ‘an immigrant has a criminal record was considered 10.7 times more important than their race and ethnic background, or 12.2 times more important than if they are from a Christian background’ (p. 12). The same report also found majority support for allowing immigrants who have a job offer to enter the UK and ‘allowing high-skilled migrants but restricting low-skilled immigration (75% support from Leavers and 65% from Remainers)’ (p. 12). The finding that public support for, or hostility towards, immigration varies according to a range of criteria is consistent with a number of other studies.[7] Studies consistently find that only a minority of the UK public are in favour of immigration controls on grounds of ethnic background.

The motivation of the majority is no guarantee against racist immigration controls. Whether someone wants racist immigration controls and whether they are willing to accept racist immigration controls are two different things. The immigration laws that were passed in the UK in 1960s were not argued for on racist grounds. As we noted in the previous section, they were accompanied by ‘race relations’ legislation and presented as part of a package which combined limiting numbers and policy aimed at integrating immigrants into British society. That does not, however, mean that there was no racist intent to immigration policy. Cabinet papers from the time show that the UK government wanted to particularly limit Black immigration, but was sensitive to the accusation of racism. In the 1960s immigration controls were widely opposed by anti-racist activists, but generally accepted by the public.

Even if we were to accept at face value the claims by government that they were not motivated by racist concerns or intent, this does not mean that immigration controls were not racist in their consequences. Immigration controls since the 1960s have consistently been racist in their operation, while governments have consistently denied that they are racist in intent. Under the New Labour government of Tony Blair, immigration policy did undergo a radical overhaul, which led to a dramatic increase in immigration. Andrew Neather, one of the advisors involved in the policy, has argued that there was an anti-racist rationale to the policy shift. One of the driving political purposes of the new policy, he has claimed, was to use mass immigration ‘to make the UK truly multicultural’.[8] In stark contradiction to this seemingly pro-immigration claim, however, the dramatic increase in immigration was accompanied by anti-immigration measures. The Blair government beefed up border security and introduced draconian policies to deter asylum-seekers and other irregular migrants. They also sought to close off avenues for immigration from Black majority Commonwealth countries. Their deterrence policies had a disproportionately negative impact not just on Black immigrants, but also on UK citizens from ethnic minority backgrounds. These policies have been pushed even further under subsequent Conservative governments, in their attempts to create a ‘hostile environment’ for irregular migrants.

Bickerton and Tuck, if asked, might well agree that, historically, UK immigration controls have been racist in practice. We don’t know, because their focus is not on immigration policy as such, but on restoring popular sovereignty to the UK by exiting the EU. Their defence of the Brexit vote from the accusation of racism does not involve denying any racist intent; rather, it involves the claim that the real substance of the vote is a demand for popular sovereignty. Bickerton and Tuck, although they don’t express it in these terms, could be interpreted as justifying the Leave vote on the grounds that leaving the EU would enable the self-emancipation of the working class. Core to their argument is the claim that Brexit is about ‘self-government and political autonomy’ (p. 10). The public cannot currently change UK immigration policy, they argue, because it is the EU, not the UK, that controls policy. After the UK leaves the EU, immigration policy will be set by the UK government, and this policy will also be open to being challenged by citizens. Bickerton and Tuck argue that granting citizenship to EU citizens currently living in the UK would give them voting rights in UK elections, and it would mean that, through the vote and other forms of political mobilisation, they could influence UK immigration policy. In this sense Brexit is conceived as a necessary precondition for any change in immigration policy, whether it is more expansive, restrictive, racist or humanist.

Their argument assumes that representative democracy provides self-government and political autonomy. It does not. Representative democracy involves, as Bickerton and Tuck themselves note, citizens delegating their power to their elected representatives. Inasmuch as power has been delegated, it is no longer under the control of the citizen. Elected representatives are free to exercise that power as they see fit, which is what politicians, political parties and government are doing when they claim that they have an electoral mandate. People who voted Leave because they wanted to ‘take back control’ were not ‘taking back control’ to themselves. They were enabling control to be taken back to Westminster, as a sovereign parliament, not to themselves.

The UK’s departure from the EU provides no guarantee of self-government by the people, as opposed to in the name of the people. And as long as the electorate are willing to allow the government to govern in their name, they are surrendering their own political autonomy. Bickerton and Tuck’s conception of self-government and political autonomy, inasmuch as it is compatible with the self-emancipation of the working-class, is analogous to the Stalinist two-stage theory of national liberation. The first task is to democratise the UK, by leaving the EU, only then will it be possible to move towards socialism.

Bickerton and Tuck’s analysis ignores the growing independent activity of workers and oppressed minorities. There are numerous small and developing actions in the UK that are grappling towards the goal of human emancipation. Immigrants are central to many of these. Workers in low-skilled, low-wage, casualised labour markets have some of the most precarious jobs in the UK. Migrant workers employed in these sectors, as union organiser Kelly Rogers points out, are ‘threatened not just with unemployment, poor working conditions and low pay, but also rising anti-immigrant sentiment and potential deportation’ (p. 336). Despite these difficult circumstances, however, migrant workers are organising and fighting back. In the process they are helping to ‘combat conservativism in trade union bureaucracies, and to build politicised, militant and more effective organised rank-and-file’ (p. 336).

Rogers gives examples from campaigns in London for better pay and working conditions—restaurant workers in Harrods, cleaners at the London School of Economics and in the London Underground, workers employed by the Picturehouse chain of cinemas—and a campaign by Deliveroo cycle couriers in Brighton. These actions have been organised through small, independent trade unions, principally the Independent Workers of Great Britain (IWGB) and United Voices of the World (UVW). The IWGB and UVW are based on a self-development model of workplace organising, in contrast to ‘a “doctor-patient relationship”, where workers wait for a quick consult with the organiser, who then cures their ills’. Instead of the standard representative model of a trade union, the IWGB and UVW promote the self-representation and self development of workers. Their members compile their own demands and plan their own campaigns based on their own experiences of the workplace. The union organisers provide guidance, while the union head office provides legal support. As Steven Parfitt notes, union members ‘are encouraged to trust their own abilities, and take control of their own campaigns’. Both unions are predominantly composed of migrant workers, but their actions do not just benefit migrant workers, they benefit all workers.

The self-emancipation of the working-class is being developed only through campaigns around pay and working conditions. There is a lot of pro-migrant grassroots activity taking place all over the UK: from the national One Day Without Us day of solidarity (between migrants and UK citizens) to local anti-deportation campaigns that spring up in support of migrants threatened with deportation. There are campaigns against immigrant detention. There are solidarity groups—such as Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants—that draw connections between different forms of oppression. There have been protests in support of EU migrants and campaigns established to fight for the rights of EU citizens in the UK, and UK citizens in the EU. New campaigns are springing up all the time. The Docs Not Cops campaign, for example, emerged in response to the attempts by the UK government to restrict migrants’ access to healthcare and to make healthcare workers into front-line border officials.

All of these forms of solidarity and protest are examples of popular sovereignty in action and do not involve delegating power to elected politicians. Grassroots political mobilisations were growing before the EU referendum was announced and will continue to grow, regardless of whether the UK does or does not end up leaving the EU. They is not dependent on Brexit––hard, soft or otherwise.

Anti-racism and human freedom

The Leave/Remain dichotomy is not the most important political divide in the UK today. There are workers on both sides, and each person usually has good reasons why they are supporting one side or the other—this, in itself, should indicate that Leave/Remain is an unhelpful, even divisive, dichotomy.

Anyone who has the goal of complete human freedom, though the ‘independent emancipatory self-activity’ of the working class and the oppressed, would have to agree that workers who voted Leave should not be dismissed as racist. The working class cannot be lectured or shamed into their own liberation. The emancipation of the working class can only come through workers’ own thought and activity.

Working-class people who are concerned about the suppression of wages, or worry about strains on public resources such as schools and hospitals, have genuine concerns. Blaming immigrants for causing these problems involves misidentifying the source of the problem. As long as workers are tied to capitalist ideas—such as the ideas that ‘our’ jobs/’our’ welfare/’our’ state belong to ‘us’ as a nation—they cannot emancipate themselves.

Challenging capitalist ideology when it manifests itself amongst workers is fundamental to developing an independent working-class perspective on the world. Those who claim to be on the left, and who defend working-class Leave voters from the accusation of racism, are not involved in the struggle to develop the self-emancipation of the working-class. These Lexiteers reproduce the distinction between mental and manual labour.[9] They forget, as Marx put it, ‘that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself … [And they] therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society’. They see their role as providing intellectual leadership to the working class. In doing so they set themselves up as a superior element in the struggle for human freedom and assign the working class to the role of followers. If these Lexiteers are hoping to lead the working class, intellectually or organisationally, then they are not trying to be part of the self-emancipation of the working-class.

The words of Eugene V. Debs, the great Victorian era American labour Union organiser, are apt in this context. The working-class, he said,

are beginning to organize themselves; they are no longer relying upon some one else to emancipate them, but they are making up their minds to depend upon themselves and to organize for their own emancipation. Too long have the workers of the world waited for some Moses to lead them out of bondage. He has not come; he never will come. I would not lead you out if I could; for if you could be led out, you could be led back again. I would have you make up your minds that there is nothing that you cannot do for yourselves.

If the Lexiteers are aiming to lead the working class, then they are invoking the working class to advance some other project—such as promoting parliamentary sovereignty, justifying immigration controls, promoting social cohesion or building the Party. They are not immersing themselves in, and learning from, the struggle for human freedom.[10]

The working class cannot emancipate themselves in practice if they do not also emancipate themselves in thought. Nationalism and the nation-state erect barriers in the mind as well as around territory. Some sections of the working class are refusing to confine their imaginations within the confines of the nation-state. We are making common cause with refugees and asylum-seekers. We are making common cause with migrant workers and with other immigrants. To emancipate ourselves we need to stand alongside refugees, asylum-seekers and migrant workers who are arguing for open borders—workers and oppressed peoples of the world, unite!

Chris Gilligan has been active in pro-migrant issues for more than a decade. He is a founding member of Open Borders Scotland. He is the author of Northern Ireland and the crisis of anti-racism (Manchester University Press, 2017).

Notes

[1] Thanks to Paul Wight for bringing this webpage to my attention.

[2] For more on this ‘post-truth’ tendency in contemporary politics see: Marxist Humanist Initiative, ‘Combatting “Post-Trust Politics,” in Practice and Theory’, in Resisting Trumpist Reaction (and Left Accommodation): Marxist-Humanist Initiative’s Perspectives for 2018, published online (11 January 2018), available here.

[3] The inclusion of Goodhart in this article may seem misplaced. Goodhart was not a Lexiteer; he claims to have voted Remain. He is also not a straightforward leftist. His ambiguous leftism is perhaps best summed up in the description of him as ‘the Left’s Enoch Powell’ (see note 5 below). I have included him here because he, like the Lexiteers being criticised in this article, viewed the Brexit vote as a revolt of the ‘left-behind’ working class and, like the Lexiteers, he sympathises with the concerns of working-class Leave voters.

[4] David Goodhart, The road to Somewhere: the new tribes shaping British politics, (Harmondsworth, Penguin, 2017), Introduction

[5] Enoch Powell was a leading figure on the right of the Conservative Party who, in the late 1960s, attempted to harness popular opposition to immigration to shift government policy from immigration control to repatriation (his speeches were also possibly made in a bid for the leadership of the Conservative Party). There was significant support for Powell, and even more support for restricting immigration, from within the working-class. See, e.g., F. Lindop, ‘Racism and the working class: strikes in support of Enoch Powell in 1968’, Labour History Review 66, No. 1 (2001), pp. 79-100; and Liz Fekete ‘Dockers Against Racism: an interview with Micky Fenn’, Race & Class 58, No. 1 (2016), pp. 55-60, available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306396816643004

[6] See Satnam Virdee, Racism, class and the racialised outsider (Houndsmill: Palgrave, 2014), for a historical overview. On recent industrial action, see e.g. Kelly Rogers, ‘Precarious and migrant workers in struggle: Are new forms of trade unionism necessary in post-Brexit Britain?’, Capital & Class 41, No. 2 (2017), pp. 336-343.

[7] For an overview, see Chris Gilligan, ‘The public and the politics of immigration controls’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41, No. 9 (2015), pp. 1373-1390. For data on public opinion see: Oxford Migration Observatory at http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/ .

[8] The anti-working class snobbery involved in this thinking is clearly expressed by Neather when he says: ‘It’s not simply a question of foreign nannies, cleaners and gardeners—although frankly it’s hard to see how the capital [London] could function without them. Their place certainly wouldn’t be taken by unemployed BNP voters from Barking or Burnley—fascist au pair, anyone?’

[9] Raya Dunayevskaya highlighted the importance that Marx attributed to the overcoming the distinction between mental and manual labour when she said that Marx demonstrated that ‘the most fundamental division of all, the one which characterized all class societies, and none more so than capitalism, is the division between mental and manual labor. This is the red thread that runs through all of Marx’s work from 1841 to 1883. This is what Marx said must be torn up root and branch’, (emphasis in the original), R. Dunayevskaya, Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1991), p. 105.

[10] Some on the Left who campaigned for Leave may have the emancipation of the working class as their goal. In joining forces with the Eurosceptic and anti-immigrant Right, however, they have subordinated the long-term goal of the emancipation of the working class to the short-term goal of leaving the EU. This type of tactical thinking is typical of Leftists who aspire to being leaders of the working class, rather than submerging themselves within the struggle for working-class self-emancipation.

This is a nice article indeed. The particular points that stand out for me are:

1) working people must emancipate themselves in thought and in practice

2) Brexit brings control back to Westminster, but not to ordinary people

But there is also one point that could have been developed more clearly: the link / or non-link between racism and supporting immigration control. Does supporting immigration control mean that one is inherently racist? You touch on this when you discuss crime and religion, but I think this could be discussed further. Many people support immigration control, and use their worry about the immigrant criminal as an excuse to hide their racist positions.

But I think the real question would be: why does one support immigration controls, is one actually siding with capitalist views? If so, then this does not help the emancipation of the working class, as you discuss in the closing section.

Yes five years later why does one support immigration controls?…I wonder why?

”then this does not help the emancipation of the working class”Has if the government is concerned about the white working class of this country or the people of it in general.The author of this piece does not care about them or their concerns Chris Gilligan argues that; “The idea that White people in the United Kingdom constitute a race or ethnic group is based on racialised thinking. It works with the logic of the race relations framework, it does not challenge it.” I wonder would he state this about Black and Asian people or would he be described a ”racist”?You wonder in a few years time of the demise of White people here and Europe was actually a replacement policy of certain groups?

I suppose you and this author will probably rejoice in this but the blood of innocent people will be of your hands but then marxists encourage this without really getting their own hands dirty.

We could refuse to print Paul James’ comment on the grounds that the last sentence is an ad hominem attack, but we are letting it go in the hopes that others will answer him.

MHI

His comment is “great replacement” garbage–note the phrase “replacement policy of certain groups.” The “great replacement” garbage is a racist and anti-Semitic conspiracy theory that incites genocide. https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2022/05/17/racist-great-replacement-conspiracy-theory-explained It has become prevalent in the US thru Tucker Carlson and the perpetrators of the Charlottesville Massacre (who chanted “Jews will not replace us”).

If Paul James is willing to renounce everything he stands for, then we can talk. Otherwise, we really need to engage with him only from the other side of the barricade.