By Andrew Kliman, Author of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital“: A refutation of the myth of inconsistency.

Some prominent radical economists and non-economists have denied that Marx’s theory of the tendential fall in the rate of profit helps to explain the current economic crisis. I want to begin by explaining why they dismiss this theory, and then argue, to the contrary, that the current crisis does have a lot to do with the tendential fall in the rate of profit as analyzed by Marx.

In the 1970s, as an outgrowth of the New Left, and because of the global economic crisis of that decade, there was a renewal of scholarship that attempted to reclaim Marx’s value theory and theories grounded in his value theory, such as his theory of the tendential fall in the rate of profit and his theory of capitalist economic crisis. But these efforts met with a strong reaction, in the form of a resurgent myth that Marx’s value theory and law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit had been proved internally inconsistent. It needs to be stressed that the resurgence of this myth of inconsistency came from within the Left; almost all of the critics of Marx’s value theory in this period, and ever since, have been Marxist or Sraffian economists.

Why does the myth of inconsistency matter? Well, internally inconsistent arguments simply cannot be correct, so a theory that is founded upon them cannot possibly explain events correctly. It mayseem to do so; it may be intuitively plausible, even convincing, and it may be consistent with all of the available evidence. Nonetheless, the fact remains that internally inconsistent arguments are always wrong, even if they accidentally happen to arrive at correct conclusions in a particular case. A theory founded upon them must therefore be rejected or corrected. For instance, in an influential 1977 work, Marx After Sraffa, Ian Steedman, a leading Sraffian economist, argued, “value magnitudes are, at best, redundant in the determination of the rate of profit (and prices of production)” (p. 202). “Marx’s value reasoning–hardly a peripheral aspect of his work–must therefore be abandoned, in the interest of developing a coherent materialist theory of capitalism” (p. 207).

One key aspect of the “internal inconsistency” critique was the so-called “Okishio theorem.” In 1961, the Japanese Marxist economist Nobuo Okishio claimed to prove that technical innovations introduced by profit-maximizing capitalists can never cause the rate of profit to fall. Thus Marx’s diametrically opposed conclusion was based on internally inconsistent reasoning. Once it was discovered during the debates of the 1970s, Okishio’s theorem caught on quickly.

Owing to the supposed mathematical rigor of their arguments, and undoubtedly owing to the changed political climate as well, Marx’s critics won these debates hands down. By the start of the 1980s, the myth that Marx’s theories of value and the falling rate of profit have been proven internally inconsistent, and therefore false, was almost unanimously accepted as fact.

This myth has since been disproved by proponents of what is now known as the temporal single-system interpretation of Marx’s value theory. I am proud to have contributed to this effort and I’ve tried to make the issues and the refutation of the myth accessible to a general audience, i.e., to explain things with minimal math and in as simple a way as I can, in Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A refutation of the myth of inconsistency, which came out in 2007.

Nonetheless, the myth of inconsistency largely persists, and it affects the debate over the causes of the current crisis. As I said at the start, some prominent radical economists and non-economists have been denying that Marx’s theory of the tendential fall in the rate of profit helps to explain the current economic crisis. As we’ll see, the reason they dismiss his theory has a lot to do with the Okishio theorem. But first let me report what they say.

Writing in the International Socialism journal last July, Fred Moseley, a prominent Marxist economist, wrote, “there has been a substantial recovery of the rate of profit in the US economy…. Three decades of stagnant real wages and increasing exploitation have substantially restored the rate of profit, at the expense of workers. This important fact should be acknowledged. … The main problem in the current crisis is the financial sector. … The best theorist of the capitalist financial system is Hyman Minsky, not Karl Marx. The current crisis is more of a Minsky crisis than a Marx crisis.” [Moseley, “Some notes on the crunch and the crisis,” http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=463&issue=119]

Similarly, an attendee at last November’s Hisotrical Materialism conference recently reported that another prominent Marxist economist, “Gérard Duménil, … mock[ed] the idea that ‘the profit rate had to be behind the crisis’. . . . [H]e thought the crisis was of financial origin and that the profit rate had been relatively steady and had little to do with it.” The same report states that Costas Lapavitsas, another well-known Marxist economist, was “also dismissive of the profit-rate line.” [Mike Beggs, Feb. 16, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20090723053856/http://mailman.lbo-talk.org/pipermail/lbo-talk/Week-of-Mon-20090216/002355.html]

Now the main reason they dismiss the notion that Marx’s law of the falling tendency of the rate of profit helps account for the current crisis is that the so-called “rate of profit” that they are talking about has indeed recovered substantially since the early 1980s. But their so-called rate of profit isOkishio’s rate of profit, the measure he used to try to prove Marx internally inconsistent, not the rate of profit that Marx talked about when he said that technological progress tends to cause it to fall.

Okishio’s rate of profit is essentially a physical measure, not a monetary or value measure, and so it actually isn’t a rate of profit in any normal sense. It has little to do with what capitalists in the real-world mean by “rate of profit,” namely their money profit as a percentage of the actual sum of moneythey’ve invested. But since Okishio supposedly disproved Marx’s theory, and since Marx’s value theory was supposedly proved to be internally inconsistent, the Marxist economists have chucked hisvalue-based rate of profit into the dustbin of history. During the last three decades, when they’ve discuss the tendency of the rate of profit, they’ve been discussing the tendency of Okishio’s physical measure.

This substitution matters a lot when the question is whether the rate of profit has recovered from the fall it underwent from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s.

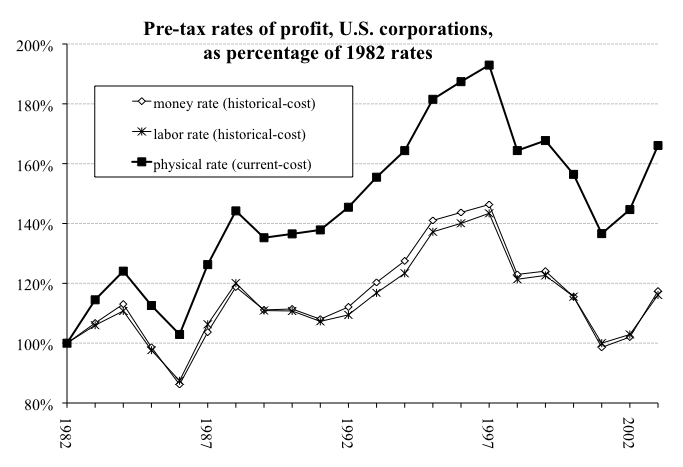

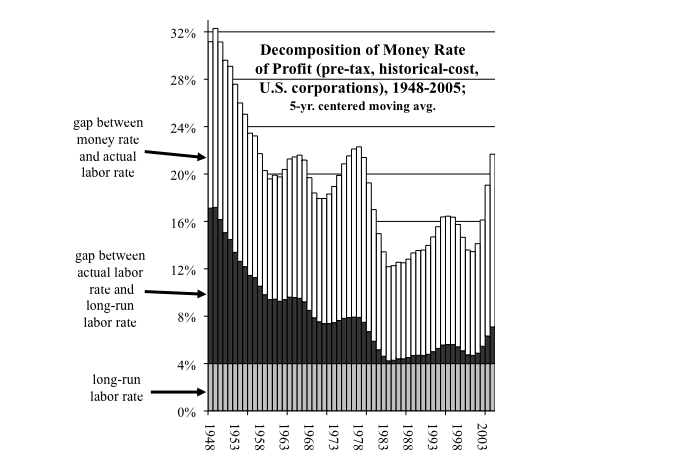

As Figure 1 shows, the physical rate of profit rose by 37% from 1982 to 2001. (All of my data come from the U.S. government–the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics–and are obtainable online for free.)

But again, the physical rate of profit isn’t a rate of profit in any real sense, and the myth of Marx’s internal inconsistency has been refuted, so we can in good conscience return to an examination of the money rate of profit, measured on the basis of the actual sums of money invested, and labor, or value, rate of profit, which we see is very closely associated with the money rate. These two rates were no higher in 2001 than in 1982. They experienced only a cyclical rise, no long-term recovery.

Given that the rate of profit hasn’t recovered, perhaps Marx’s theory can help to explain the current economic crisis after all. I will now argue that it does help. In brief, my view is this: The rate of profit heads toward “the long-run rate of profit.” At the start of a new boom, the rate of profit is well above the long-run rate of profit, so it tends to fall over time. This situation persists unless there’s sufficient “destruction of capital.” Destruction of capital restores profitability, and thus ushers in a new boom. This is what happened in the Great Depression and World War II. But there was insufficient destruction of capital in the economic crises of the mid-1970s and early 1980s. Rather than allowing there to be a depression (and subsequent boom!), policy-makers have continually encouraged excessive expansion of debt. This artificially boosts profitability and economic growth, but in an unsustainable manner; it leads to repeated debt crises. The present crisis is the most serious and acute of these. Policy-makers are responding by again papering over bad debts with more debt, this time to an unprecedented degree.

My first theoretical point in the above sketch is that the rate of profit heads toward the long-run rate of profit. So what I’m calling the “long-run” rate of profit is the rate toward which the actually observed rate of profit tends in the long run, all else being equal. What is this long-run rate? According to Marx’s theory, all profit comes from workers’ labor. Thus the long-run rate of profit depends in part upon the rate of growth of employment. This is held down by labor-saving technical progress. The long-run rate also depends upon the share of profit or surplus-value that is reinvested.

There are two other factors determining the value of the long-run rate of profit: the relationship between profits and wages, and the rise in money prices above the real value of goods and services, which, according to Marx’s theory, is determined by labor-time. But just for the moment, let’s ignore these factors. In other words, let’s consider what the long-run rate of profit would be if the relationship between profits and wages were constant, and money prices didn’t rise above real values. (1)

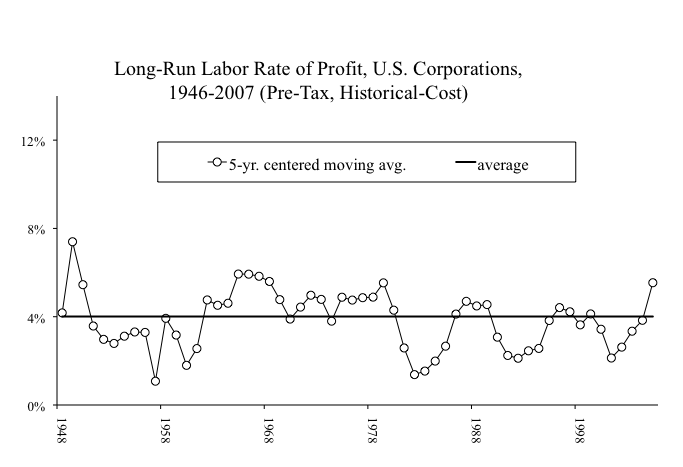

Over the last 61 years in the U.S., this long-run rate of profit, which I’m calling the long-run labor rate, as distinct from the long-run money rate of profit, has been trendless, a constant 4% on average.

My second point in the above theoretical sketch was that, at the start of a new boom, the rate of profit is well above the long-run rate of profit, so it tends to fall over time.

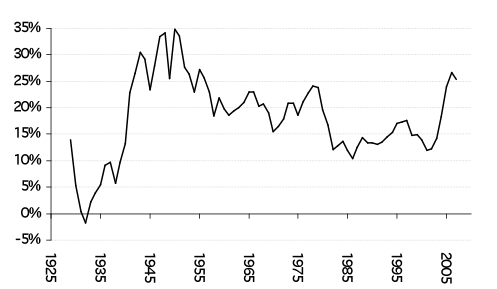

Money Rate of Profit, US Corporations, 1929-2007

(Before-tax profits as % of historical cost of fixed assets)

The next slide shows that the money rate of profit did in fact start off much higher in the boom that began after the Great Depression, and that it has tended to fall consistently since then.

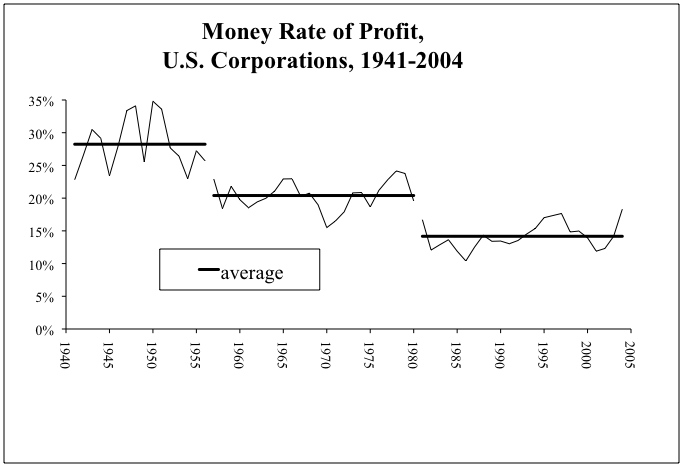

A closer look at this graph reveals that there have been three distinct periods since the start of World War II. From 1941 through 1956, the rate of profit averaged 28%, falling to 20% in the 1957-1980 period, and falling further to 14% in the period from 1981 through 2004. What caused the fall?

Well, according to the theory presented above, there is the long-run labor rate of profit, 4%. Then there’s the actual labor rate of profit, which is what the money rate of profit would have been if money prices didn’t rise above real values. We see a clear tendency for the actual labor rate of profit to head toward the long-run labor rate, just as the theory suggests.

Then there’s the excess of the money rate over the actual labor rate. Prices have indeed consistently risen in relationship to the real values of goods and services, and this consistently boosts the money rate of profit over the labor rate. But the gap between the two rates has been roughly constant–in fact, it has fallen by several percentage points since the rate of inflation came down in the early 1980s. And since this gap is roughly constant, the fall of the labor rate of profit toward its long-run level has been accompanied by a fall, of basically the same extent, in the money rate of profit. These results match the theory to a greater degree than I expected before I began this analysis.

My next point of in the above theoretical sketch was that this tendency of the rate of profit to fall toward its long-run level persists unless there’s sufficient “destruction of capital.” This is a key concept of Marx’s theory of capitalist crisis. By “destruction of capital,” he meant not only the destruction of physical capital assets, but also, and especially, of the value of capital assets.

In an economic slump, machines and buildings lay idle, rust and deteriorate, so physical capital is destroyed. More importantly, debts go unpaid, asset prices fall, and other prices may also fall, so the value of physical as well as financial capital assets is destroyed. Yet as I noted earlier, the destruction of capital is also the key mechanism that leads to the next boom. For instance, if a business can generate $3 million in profit annually, but the value of the capital invested in the business is $100 million, its rate of profit is a mere 3%. But if the destruction of capital values enables new owners to acquire the business for only $10 million instead of $100 million, their rate of profit is a healthy 30%. That is a tremendous spur to a new boom.

Thus the post-war boom came about, I believe, as a result of a massive destruction of capital that occurred during the Great Depression and World War II. One measure of that boom is the rise in the rate of profit that we saw earlier, from -2% in 1932 to 30% in 1943.

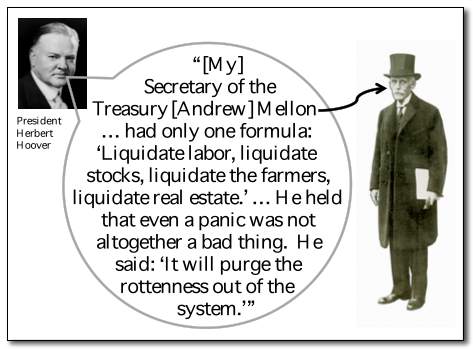

At the start of the Great Depression, the destruction of capital was actually advocated by conservative economists. This was called “liquidationism.” According to Herbert Hoover, his Treasury Secretary, the financier Andrew Mellon, advocated it as well.

But in the 1970s and thereafter, policymakers in the U.S. and abroad have understandably been afraid of a repeat of the Great Depression. They have therefore repeatedly attempted to retard and prevent the destruction of capital. This has “contained” the problem, while also prolonging it. As a result, the economy has never fully recovered from the slump of the 1970s, certainly not in the way in which it recovered from the Great Depression. The failure of the rate of profit to recover is one indicator of the lack of a new boom.

The result is a relative sluggishness of the economy. But the sluggishness has continually been papered over by an ever-growing mountain of debt. For instance, reduced corporate taxes have boosted the after-tax rate of profit relative to the pre-tax rate, but this boost has been paid for by $2.5 trillion of additional public debt. Almost all of the remaining increase in the government’s indebtedness is used to cover lost revenue resulting from reduced individual income taxes. These tax reductions have propped up consumer spending and asset prices artificially. Similarly, easy-credit conditions have led to inflated home prices and stock prices, and this has allowed consumers and homeowners to borrow more and save less. Americans saved about 10% of their after-tax income through the mid-1980s, but the saving rate then fell consistently, bottoming out at 0.6% in the 2005-2007 period.

Thus, in the period since the crisis of the mid-1970s, there have been recurrent upturns that have rested upon debt expansion. For that reason, they have been relatively short-lived and unsustainable. And the excessive run-up of debt has resulted in recurrent crises, such as the savings and loan crisis of the early 1990s, the East Asian crisis that spread to Russia and Latin America toward the end of the decade, the collapse of the dot-com stock market boom shortly thereafter, and now the biggest crisis of all, brought on by the busting of housing market bubble.

Policymakers are responding to this crisis with more of the same–much, much more. The U.S. government is borrowing a phenomenal amount of money, for TARP, Obama’s stimulus package, the new PPIP (Son of TARP) bailout of the banks, and so forth. If these measures succeed–and that is still far from a sure thing–full-scale destruction of capital will continue to be averted. But if my analysis is correct, the consequences of success will be continuing relative stagnation and more debt crises down the road, not a sustainable boom. To repeat, unless sufficient capital is destroyed, profitability cannot return to a level great enough to usher in a boom. And given the huge increase in debt that the U.S. government is now taking on, the next debt crisis could be much worse than the current one. It is therefore not unlikely that the next wave of panic that strikes the financial markets will be even more severe than the current one, and have more serious consequences.

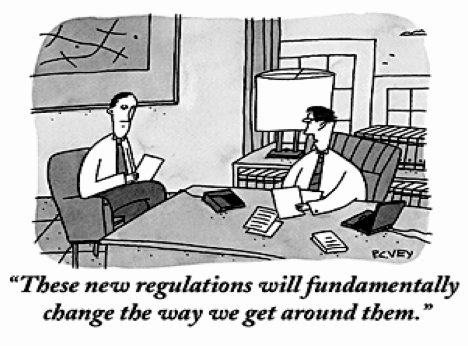

But what about the notion that the crisis could have been averted by regulation, and that the next crisis can be averted by regulation? For decades, and until very recently, we heard a lot about how “free-market” capitalism is supposedly more successful than regulated capitalism. Now we’re hearing a lot about regulated capitalism as the new solution.

But consider the savings and loan crisis of two decades ago. Thousands of S&Ls collapsed; the government eventually had to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to repay depositors. This crisis was a failure precisely of regulated capitalism. The S&Ls were very heavily regulated; both the interest rates that they paid on deposits and the rates they charged for mortgage loans were fixed by the government. The S&Ls were known as a 3-6-3 industry: bring in funds by paying 3% on deposits, lend them out at 6%, and be on the golf course by 3 in the afternoon. Very boring, but very safe and stable.

But one thing that Keynesian policies and regulations didn’t regulate, and which they weren’t able to prevent, was the spiraling-upward inflation of the mid- and late-1970s. When inflation took off, the 6% they were getting on mortgage loans didn’t come close to the rate of inflation, which averaged 9.4% from 1974 through 1981. So in “real,” or inflation-adjusted, terms, the S&Ls were losing money hand over fist. Also, the measly 3% interest that S&Ls were allowed to offer depositors was even further below the rate of inflation, so in “real” terms, depositors were losing tons of money by keeping their deposits in the S&Ls. But this latter situation led to the rapid growth of an unregulated alternative: money market mutual funds, which were paying interest rates that more than made up for inflation. Depositors were very happy to have this alternative to the regulated S&Ls. They fled the S&Ls and put their money in the money market mutual funds.

Now Congress eventually lifted the ceiling on the rates that S&Ls could offer depositors, and the ceiling on the rates they could charge for their loans. But the S&Ls were still losing massive amounts of money on the mortgages they had made in the 1950s and 1960s, which were still bringing in 6% interest. The only way they could stay afloat was to make new loans that were riskier than home mortgage loans and which therefore paid higher interest. So Congress eventually undid a Depression-era law which stipulated that the S&Ls were to make home mortgage loans only. The S&Ls began to make very risky real estate and business loans in order to make up for their losses on old loans and cover their costs of borrowing depositors’ funds. A lot of these loans never paid off, and in the end the industry essentially collapsed.

The basic problem with the notion that regulated capitalism is somehow better than free-market capitalism is the simple fact that, in the end, capitalism can’t be regulated.

P.C. Vey, The New Yorker, March 9, 2009

This was acknowledged recently by Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel Laureate and former World Bank chief economist. In mid-September, he wrote an article that proposed a whole slew of new regulations and laws. But Stiglitz ended by conceding, “These reforms will not guarantee that we will not have another crisis. The ingenuity of those in the financial markets is impressive. Eventually, they will figure out how to circumvent whatever regulations are imposed.” I think this is exactly right. [Stiglitz, “How to prevent the next Wall Street crisis,” CNN.com, September 17, 2008]

Stiglitz did go on to say, “But these reforms will make another crisis of this kind less likely, and, should it occur, make it less severe than it otherwise would be.” [ibid.] That doesn’t make sense, however. If the financial markets will eventually circumvent whatever regulations are imposed, then, once they do, the next financial crisis will be just as likely and just as severe as it would have been otherwise. The best that can be said for new laws and regulations is that they can delay the next crisis, while the markets are still finding ways to circumvent the regulators. And a delay of the crisis means more artificial expansion through excessive borrowing in the meantime, so that the contraction will be more severe when the bubble does finally burst.

Footnotes:

(1) If prices equaled values, then the rate of profit could be expressed as a ratio of variables measured in terms of labor-time rather than as a ratio of variables measured in terms of money. So let S stand for surplus labor, i.e., surplus value in labor-time terms; let L stand for living labor (or employment, a close approximation); and let C stand for capital advanced in terms of labor-time). In the long run, S/C, which is the rate of profit measured in terms of labor-time, tends toward the incremental, or long-run, rate: . Now if the relationship between profit and wages were constant, then S/L, surplus-labor per worker, would be constant. Under this assumption,

. My estimates of the long-run labor rate of profit are estimates of this ratio. In a paper I intend to complete within the next few weeks, the long-run rate of profit and its relationship to the actual labor-time and money rates of profit will be discussed in more detail.

13 Comments on “On the Roots of the Current Economic Crisis and Some Proposed Solutions”

1kmb said at 2:38 am on April 24th, 2009:ok, ok, so Marx’s LTRPF is correct. Still, I don’t see a causal model of HOW a drop of say 1 or 2% in the NFC (money) profit rate HAS TO lead to a severe recession. that’s still a missing link. One could even theorise, that a fall in the profit rate may actually push up investment, because of “coerced (competitive) investment” (J Crotty had a paper on this)…

this particular crisis seems to be a combination of demand-side problems (stagnant/declining wages for a large part of the pop., compensated by household borrowing), developments in the financial sector (collapse of the securitisation modell), bursting of a huge asset bubble (8 trillion $ real estate bubble, all collateralised…pushing down consumer spending) AND a “normal” LTRPF-induced crisis in business investment…

why does it have to be ONLY the LTRPF that explains the crisis?2Andrew Kliman said at 5:17 pm on April 24th, 2009:Dear kmb,1. You refer to “the NFC (money) profit rate.: I assume “NFC” stands for non-financial corporations.” But the data in my article are for all U.S. corporations, financials and non-financials combined.2. You write that you “don’t see [in my article] a causal model of HOW a drop of say 1 or 2% in the NFC (money) profit rate HAS TO lead to a severe recession. [T]hat’s still a missing link.” You don’t see this in the article because it isn’t there. I didn’t argue that a fall in the rate of profit was the direct and immediate (proximate) cause of the crisis.

What I argued (in the text between the 1st 2 graphs was this:

“the rate of profit … tends to fall over time. This situation persists unless there’s sufficient ‘destruction of capital.’ … But there was insufficient destruction of capital in the economic crises of the mid-1970s and early 1980s. Rather than allowing there to be a depression (and subsequent boom!), policy-makers have continually encouraged excessive expansion of debt. This artificially boosts profitability and economic growth, but in an unsustainable manner; it leads to repeated debt crises.”

Then there are three paragraphs in the article (right below the Hoover-Mellon figure) that elaborate on this:

“the economy has never fully recovered from the slump of the 1970s, …

“The result is a relative sluggishness of the economy. But the sluggishness has continually been papered over by an ever-growing mountain of debt. For instance, reduced corporate taxes … for by $2.5 trillion of additional public debt[, … and] lost revenue resulting from reduced individual income taxes [that has] propped up consumer spending and asset prices artificially. Similarly, easy-credit conditions have led to inflated home prices and stock prices, and this has allowed consumers and homeowners to borrow more and save less. …

“Thus, … there have been recurrent upturns that have rested upon debt expansion. For that reason, they have been relatively short-lived and unsustainable. And the excessive run-up of debt has resulted in recurrent crises, such as the savings and loan crisis of the early 1990s, the East Asian crisis that spread to Russia and Latin America toward the end of the decade, the collapse of the dot-com stock market boom shortly thereafter, and now the biggest crisis of all, brought on by the busting of housing market bubble.”

So while it seems to me that you’re right to insist on an intermediate link between the tendential fall in the rate of profit and the outbreak of economic crisis, I don’t agree that such a link is “missing.” The article identifies *several* such links: sluggishness, fiscal and monetary policies, growing debt (and debt and more debt), and recurrent bubbles and the bursting of these bubbles.

3. You write, “why does it have to be ONLY the LTRPF [law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall] that explains the crisis?” It doesn’t have to be, and I don’t think it is. I don’t see how the above analysis can be accused of being a monocausal explanation.

4. I agree with you about the most important “demand-side problems.” I didn’t have space to discuss them all in this article, which combines a couple of short talks I gave last week. But I have discussed them elsewhere. In “A Crisis for the Centre of the System,” which was published last fall in the International Socialism journal, I discussed in detail the *proximate* causes of the current crisis-without even mentioning the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit, since I was just focusing there on the proximate causes. And I have discussed the links between the tendential fall in the rate of profit and the crises that I sketched above in somewhat more detail in “‘The Destruction of Capital’ and the Current Economic Crisis.” For instance, in the latter article (a slightly revised version of which will appear this summer in Socialism & Democracy), I write, “the effects of declining real wages have until recently been mitigated by easy-credit conditions and rising prices of homes and stocks, brought about by Federal Reserve policies and other means.” This is substantially identical to what you wrote above. (Both of the papers cited here can be accessed at http://akliman.squarespace.com/crisis-intervention.)

5. The KEY point in all this is that “demand-side” problems and “supply-side” problems (i.e., the tendential fall in the rate of profit) are not two separate things. I think you do separate them in your comment above. I.e., you treat them as separate but co-contributory causes of the economic crisis.

I don’t think this is right. And I especially don’t think it makes sense to COUNTERPOSE a “Minsky crisis” to a “Marx crisis”-as Fred Moseley does (see the 8th paragraph of the above article). As I have noted in another article (“Debt, Economic Crisis, and the Tendential Fall in the Profit Rate: A temporal perspective,” accessible at the same page of my website):

“By emphasizing the excessive increase in indebtedness – speculative and ‘Ponzi’ financing – that takes place in tranquil times, [Minsky’s ‘financial instability hypothesis’] offers highly valuable insights into the conditions that permit ‘shocks’ to the economy to develop into a full-blown crisis. Yet the excessiveness of the debt burden is itself left unexplained. With reference to *what* has it become excessive? Just as writers like Brenner and Greider need to explain why demand cannot keep pace with production, finance-based accounts of crisis need to explain why the economy’s ability to absorb credit cannot keep pace with its creation. Again, what determines the growth of demand, and what determines the volume of debt that is sustainable? Only by answering such questions does one move from tautology to explanation. …

“what makes debt burdens excessive is debt expansion that is too great *in relation to* the new value generated. The same imbalance likewise makes Ponzi finance a destabilizing factor, rather than something sustainable in the long term.”

And so we return to the “supply-side”-the production of value-not as something *opposed* to the “demand-side” problems, not as the monocausal explanatory factor-but as something that helps create the “demand-side” problems, something that *conditions* and *sets limits* upon the growth of demand in the long-term.

6. In 1986, Raya Dunayevskaya wrote an insightful analysis, “Capitalist Production/Alienated Labor,” on this issue that is still worth reading (and re-reading). It’s a critique of the notion, put forward at the time especially by Peter Drucker, that employment was becoming uncoupled from production, financial capital movements were becoming increasingly uncoupled from real capital investment, and industrial production was becoming uncoupled from the whole economy.

I think the current crisis shows that she (and Marx) were right: although the relationships between these “opposites” are very mediated, not direct, and although these relationships may not be immediately apparent, they cannot, when all is said and done, be “uncoupled.”

Thus Dunayevskaya wrote that the new phenomena (robotization, financialization, “post-industrial” economy) were “hiding the essence, but not in order to dismiss them as “inessential” or *reduce* them to the essence: “It is necessary to work out the new and concrete forms as they appear.”

They need to be worked out precisely as “forms of appearance,” i.e., not as something counterposed to or separate from the essence, but as the forms in which the essence makes its appearance. That’s what I’m trying to do.

Sorry if I’ve gone on too long. These are not simple matters.

3kmb said at 1:43 am on April 26th, 2009:vow. Thanks for the detailed and exhaustive answer. My first comment was indeed somewhat imprecise and even unfair, I’m sorry…however, I still have some reservations left, I’ll put them down soon, please look back in some time…

thanks.4Andrew Kliman said at 4:36 pm on April 27th, 2009:OK, kmb. I look forward to your further comments.

5kmb said at 7:00 pm on May 14th, 2009:oh, merdre. I wrote a long answer but accidentally pressed Refresh so it was all lost…anyway, to put it briefly: my main problem is that I don’t see a precise model of HOW a drop in profitability leads to economic slowdown and the resulting problems (debt, asset bubbles etc.).

Now I know that this particular article is for a wider audience, and this is not a scientific journal, so it would be silly of me to demand a quantitative model here…but, my problem is that I’m unaware of any such quantitative macroeconomic models in Marxian studies. This may very well be my own limitation, since I’m basically a newcomer to the whole field…

So, once again, the question I would ask is: do we know for certain, is it quantitatively proven, that investment growth and aggregate economic growth is profitability-led?

It sure seems logical (in Marxian theory), but is it true for all economies all the time? (post-keynesians/Kaleckians talk of stagnationist and exhilarationist economies…the former (if I understood it correctly) are not profitability-led (or not profit-share-led, which is not quite the same, but similar))

It seems, there are at least certain cases, when they are not: recently I read some studies by PK economists Ö Onaran and E Stockhammer where they analyse the growth patterns of the Turkish economy and find that it is not primarily led by profitability, rather by aggr. demand…this also seems to be true for certain developed European economies.

So: even if the LTRPF is correct, I’m not sure if pointing out a fall in profitability is necessary to explain economic slowdown and the emergence of crisis tendencies.Thanks,

Mihaly Koltai (Hungary)6kmb said at 7:02 pm on May 14th, 2009:ohh, my last sentence should be: I’m not sure if pointing out a fall in profitability is ENOUGH (sufficient) to explain economic slowdown and the emergence of crisis tendencies.

7Andrew Kliman said at 1:18 pm on May 22nd, 2009:Hi kmb,1. Actually, my argument is not that “a drop in profitability leads to economic slowdown and the resulting problems (debt, asset bubbles etc.).”My argument is rather that the drop in profitability has led to rising debt and asset bubbles. It could be that policy has been orienting to restoring profitability directly rather than restoring economic growth. I’m not saying that this is so, I don’t know. The point is just that my argument doesn’t stand or fall on a direct relationship between profitability and growth of GDP and/or investment.

Also, one facet of my argument is that the increasing indebtedness pumps up economic growth and profitability artificially. So I wouldn’t *necessarily* expect to see a slowdown in economic growth here as a result of the drop in profitability (though average annual per-capita GDP growth in the U.S. was about 25% less in the 1973-2003 period than in the 1950-1973 period).

An appropriate empirical test would look at what the relationship between movements in the rate of profit and movements in what economic growth *would have been* in the absence of the debt expansion. That’s a very tricky thing to try to get at.

2. One thing that does seem clear is that changes in profit have caused changes in investment, not vice-versa. Using BEA figures, I computed the correlations between the annual change in before-tax profits and the annual change in gross investment (for all corporations) between 1948 and 2003.

The correlation between THIS year’s change in investment and THIS year’s change in profits is 0.39.

The correlation between THIS year’s change in investment and NEXT year’s change in profits is -0.11. So it doesn’t look as though changes in investment spending have caused changes in profit.

The correlation between THIS year’s change in investment and LAST year’s change in profits is 0.52. So changes in profit do seem to have been a factor causing changes in investment spending.

3. You ask, “do we know for certain, is it quantitatively proven, that investment growth and aggregate economic growth is profitability-led? It sure seems logical (in Marxian theory), but is it true for all economies all the time?”

I don’t know how anyone could know what’s true for all economies all the time. I’m certainly making no such claims. I’m trying to explain the phenomena that *have* taken place, not say what *must* take place.

The reason why the link between profitability and capital accumulation is logical is that, BY DEFINITION,

(cap. accum. rate) =

(share of profit accumulated) x (rate of profit)So if the rate of profit falls, then-all else being equal-the rate of capital accumulation will fall. But it’s not possible to say that this must be true at all times in all places, not would I expect it to be true at all times in all places. That’s because, if the rise in the share of profit accumulated is greater, in percentage terms, than the fall in the rate of profit, then the rate of capital accumulation will rise.

But why should I care whether something is true at all times in all places? It’s not true at all times in all places that if you drop an object, it will tend to fall.

BTW, nothing above is meant to endorse the notion that economic growth has ever, anywhere, been led by aggregate demand rather than profitability. I don’t know that this is so and, in fact, I don’t even know what it means. If economic growth is growth of GDP, and aggregate demand is GDP (or GDP minus inventory accumulation), then the “fact” that changes in aggregate demand lead to changes in economic growth is either a tautology or extremely close to one.

8jonathan morton said at 9:46 am on August 10th, 2009:Belatedly

a) Have you or some other marxist economist been able to access any mainsteam publication (eg The Guardian)to explain your thesis to a bourgeois audience?b) If you (or another) were to attempt a), would the following make sense to such an audience “Okishio’s rate of profit, the measure he used to try to prove Marx internally inconsistent, is not the rate of profit that Marx talked about” ” Okishio’s rate of profit is essentially a physical measure, not a monetary or value measure, and so it actually isn’t a rate of profit in any normal sense.” Perhaps you could further elucidate for me.c) For me the problem is compounded by “what capitalists in the real-world mean by “rate of profit,” namely their money profit as a percentage of the actual sum of money they’ve invested.” Surely this is an area in dispute eg Carchedi’s critique of Brenner in H M (?4) (Brenner symposium) has it that this definition is incompatible with Marxist analysis. For him the marxist rate of profit is c+v/s, and the bourgois c/s

d) You juxtapose “what capitalists in the real-world mean” with “the rise of money prices above real values” For capitalists value is given by price

e) Again “real value .. is determined by labour time” is the subject of much marxist debate (Diane Elson)

f) no-one experiences a tendency of the rate of profit to fall. The explanations about what is falling and whether it really is falling tend to get hopelessly convoluted. For instance ” Over the last 61 years in the U.S., this long-run rate of profit, which I’m calling the long-run labor rate, as distinct from the long-run money rate of profit, has been trendless, a constant 4% on average.”

Surely its either constant or else its fallingits fallingg) “the economy has never fully recovered from the slump of the 1970s, certainly not in the way in which it recovered from the Great Depression.” Surely the economy did not recover as a result of (the destruction of capital in) the Great Depression. It recovered as a result of rearmament and military expenditure

Reverting to a) above, it appears that the concept of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is too abstract, unobservable in everyday life, and subject to yoomuch dispute re categories and definitions, to be in any way useful as an explanatory model.

why not then something along the lines of

In “classic capitalism” the industrialist made a profit making scythes. He would convert the profit in the from of cash into productive capital by expanding production, installing more steam hammers and selling

more scithes at home and abroadIn “late capitalism” the industrialist makes a profit making cars. He cannot convert the profit in the from of cash into productive capital by expanding production – there is already over production of cars and overcapacity in existing plant. So he has to find other ways of converting cash profits into capital that (is expected to) expand its value at or above the av rate of interest. Hence profits are channelled not into expanded production,but into mechanisms that boost consumption in various ways – through gnmt bonds, mortgages, private credit etc (fictitious capital). Which leads to the exponential expansion of credit.

Here streams of revenue that are to be generated in the productive economy tomorrow, are to be used up to realize the value of the outputs of the productive economy today. When tomorrow comes the purchasing power necessary to realize the value of tomorrows outputs will have in part been used upto realize todays outputs. The problem (production without regard to the market through which the value of outputs is to be realized) is here deferred and exacerbated

There comes a time when the expansion of credit looses touch with the steams of revenue actually generated in the productive economy, at which time the scrip becomes worthless, and (fictitious) capital is destroyed, credit is no longer available, and the economy implodes

None of this is in opposition to “the tendency ………to fall” – in fact the disproportion between on the one hand overaccumulation, overcapacity and overproduction, and on the other hand falling value of each unit of ouput and inelastic demand, are expressed in this tendency.

But the categories descibed are all tangible and a part of everyday discourse.So any answers to a) above?

9Andrew Kliman said at 7:42 am on August 11th, 2009:You: a) Have you or some other marxist economist been able to access any mainsteam publication (eg The Guardian)to explain your thesis to a bourgeois audience?Me: No. Why would a bourgeois audience want to hear a Marxist-Humanist analysis, and why would a bourgeois publication want to publish one?If popularity were my aim, I could perhaps repeat tired and threadbare tautologies about overaccumulation, overcapacity, and overproduction. Better yet, the MHI could turn its website into a porno site.

You: b) If you (or another) were to attempt a), would the following make sense to such an audience “Okishio’s rate of profit, the measure he used to try to prove Marx internally inconsistent, is not the rate of profit that Marx talked about” ” Okishio’s rate of profit is essentially a physical measure, not a monetary or value measure, and so it actually isn’t a rate of profit in any normal sense.” Perhaps you could further elucidate for me.

Me: What part of this don’t you understand?

You: c) For me the problem is compounded by “what capitalists in the real-world mean by “rate of profit,” namely their money profit as a percentage of the actual sum of money they’ve invested.” Surely this is an area in dispute eg Carchedi’s critique of Brenner in H M (?4) (Brenner symposium) has it that this definition is incompatible with Marxist analysis. For him the marxist rate of profit is c+v/s, and the bourgois c/s

Me: Huh? Who is “him”? And do you mean s/(c+v) and s/c? And why does it matter that something is in dispute? The theory that the Sun is the center of the solar system and the planets orbit around it was long in dispute. Does that make it incorrect? Or was it incorrect until it became correct when and because it became popular? And please READ what I wrote: “what CAPITALISTS IN THE REAL-WORLD mean by ‘rate of profit.'” Disputes about “Marxist analysis” are irrelevant to my point. Right?

You: d) You juxtapose “what capitalists in the real-world mean” with “the rise of money prices above real values” For capitalists value is given by price

Me: If “juxtapose” means “include in the same article,” I plead guilty. Otherwise, I’m innocent. I DISTINGUISHED, clearly and precisely, between “the actually observed rate of profit”-the one that capitalists in the real world know about-and “what I’m calling the ‘long-run’ rate of profit … the rate toward which the actually observed rate of profit tends in the long run, all else being equal.” And I’m quite aware that “[f]or capitalists value is given by price.” That’s why I wrote, that one of the “factors determining the value of the long-run rate of profit”-not the value of the actually observed rate-is “the rise in money prices above the real value of goods and services, which, ACCORDING TO MARX’S THEORY, is determined by labor-time.” Again, please READ what I wrote.

You: e) Again “real value .. is determined by labour time” is the subject of much marxist debate (Diane Elson)

Me: Again, please READ what I wrote: “the real value of goods and services, which, ACCORDING TO MARX’S THEORY, is determined by labor-time.” Whatever Elson thinks or thought is irrelevant to my point, which is about what Marx thought. And please QUOTE me properly, without clever ellipses that serve to hide the fact that I was referring to Marx’s theory and therefore the fact that your point is irrelevant to it.

Once again, your strange notion that something can’t be correct if it is disputed rears its head. So let me repeat my questions: The theory that the Sun is the center of the solar system and the planets orbit around it was long in dispute. Does that make it incorrect? Or was it incorrect until it became correct when and because it became popular?

You: f) no-one experiences a tendency of the rate of profit to fall. The explanations about what is falling and whether it really is falling tend to get hopelessly convoluted. For instance ” Over the last 61 years in the U.S., this long-run rate of profit, which I’m calling the long-run labor rate, as distinct from the long-run money rate of profit, has been trendless, a constant 4% on average.”

Surely its either constant or else its fallingits fallingMe: How do you know that “no-one experiences a tendency of the rate of profit to fall”? Maybe they experience it and just aren’t aware that they experience it (and its effects). Most people weren’t aware that they experienced the gravitational force that the Sun exerts on the earth, but they kept orbiting the Sun year after year nevertheless.

“Vulgar economy actually does no more than interpret, systematise and defend in doctrinaire fashion the conceptions of the agents of bourgeois production who are entrapped in bourgeois production relations. It should not astonish us, then, that vulgar economy feels particularly at home in the estranged outward appearances of economic relations in which these prima facie absurd and perfect contradictions appear and that these relations seem the more self-evident the more their internal relationships are concealed from it, although they are understandable to the popular mind. But all science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided.” [Marx, Capital, vol 3, chap. 48]

And in this case, you quote me correctly, but for some reason don’t READ the distinction I made, EVEN THOUGH I USED THE WORD “DISTINCT”:

“Over the last 61 years in the U.S., this long-run rate of profit, which I’m calling the long-run labor rate, as distinct from the long-run money rate of profit, has been trendless, a constant 4% on average.”

And so you think I’m getting “hopelessly convoluted” and failing to understand that “its either constant or else its fallingits falling,” when the actual problem is that you haven’t READ carefully enough to notice that there is more than one “it” here. One “it” is the observed rate of profit, which has tended to fall. Another “it” is the actual but not directly observed “labor rate of profit,” which has also tended to fall. A third “it” is “the long-run labor rate,” which has been constant on average. That one thing is constant while other things are falling doesn’t count as an internal contradiction.

You: g) “the economy has never fully recovered from the slump of the 1970s, certainly not in the way in which it recovered from the Great Depression.” Surely the economy did not recover as a result of (the destruction of capital in) the Great Depression. It recovered as a result of rearmament and military expenditure

Me: Surely? My data indicate that the (observed) rate of profit in the US rose from -1.8% in 1932 to 9.1% in 1937, well before rearmament. And the postwar boom and recovery of profitability persisted well after the humongous amount of government borrowing to finance the war had ended. Federal government spending fell by 77% between 1944 and 1947, and national defense spending fell by 81%. Let me repeat that: IT FELL BY EIGHTY-ONE PERCENT. All kinds of war-related businesses had to shut down or switch to other lines of production. And yet the economy did not sink back into Depression or even into the kind of relative stagnation we’ve experienced (whether we’re aware of it or not) during the last third of a century. The observed rate of profit, according to my computations remained just as high, on average, between 1946 and 1956 as it was between 1941 and 1945.

You: Reverting to a) above, it appears that the concept of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is too abstract, unobservable in everyday life, and subject to yoomuch dispute re categories and definitions, to be in any way useful as an explanatory model.

Me: In contrast to, say, the heliocentric theory of the solar system, which is not abstract, can be directly observed in daily life, and which was never the subject of dispute “re categories and definitions” (see Kuhn-part of what the theory’s opponents MEANT by “earth” was something that doesn’t move)?

You: why not then something along the lines of […] In “late capitalism” the industrialist makes a profit making cars. He cannot convert the profit in the from of cash into productive capital by expanding production – there is already over production of cars and overcapacity in existing plant. So he has to find other ways of converting cash profits into capital that (is expected to) expand its value at or above the av rate of interest.

Me: Here’s why not: “overproduction” and “overaccumulation” are not explanatory concepts. They are mere tautologies.

When there’s an economic slump, guess what? Stuff doesn’t sell. Gee, must be because of overproduction (compared to what can sell – during the slump). Must be because of overaccumulation (compared to can profitably be employed – during the slump). No question-begging here. No smuggling in of the slump in an attempt to explain the slump. No, siree. Just good ol’ common sense. The outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincide; all science is superfluous. Quick, call the Guardian!

Why don’t you throw in “inadequate effective demand” for good measure? When there’s an economic slump, guess what? Stuff doesn’t sell. Gee, must be because of inadequate effective demand (… during the slump). Might as well say that opium puts people to sleep because of its dormative power. That’s something your bourgeois Guardian audience can make sense of right quick.

But I suspect that there’s what Marx called “the semblance of a profounder justification” lurking in the background of your remark. There is such a semblance in Baran and Sweezy’s Monopoly Capital: underconsumptionism.

“That commodities are unsaleable means only that no effective purchasers have been found for them, i.e., consumers (since commodities are bought in the final analysis for productive or individual consumption). But if one were to attempt to give this tautology the semblance of a profounder justification by saying that the working-class receives too small a portion of its own product and the evil would be remedied as soon as it receives a larger share of it and its wages increase in consequence ….” [Marx, Capital, vol. 2, chap. 20]

If you want to discuss that, I’ll be happy to tell you why I think underconsumptionism rests on a dogma for which there’s no empirical or logical support, and why it makes no sense.

As for the rest of your theory, let me simply ask the following. You write, “the disproportion between on the one hand overaccumulation, overcapacity and overproduction, and on the other hand falling value of each unit of ouput and inelastic demand, are expressed in this tendency. But the categories descibed are all tangible and a part of everyday discourse.”

“Inelastic demand” is part of everyday discourse? And it’s tangible, right? So can you please take a picture of it and send it to me?

You: So any answers to a) above?

Me: Yeah. All science would be superfluous if the outward appearance and the essence of things directly coincided. But they don’t. So I have work to do, and if you’re done toying with me, may I suggest that you toy with Edward Witten (http://www.sns.ias.edu/~witten/) instead? Bet he’d get a big chuckle out of

* “make sense to such an audience,”

* “no-one experiences,”

* “Surely,”

* “Surely,” (again),

* “too abstract, unobservable in everyday life, and subject to yoomuch dispute re categories and definitions, to be in any way useful as an explanatory model,”and, last but not least,

* “the categories descibed are all tangible and a part of everyday discourse.”

10Sparky said at 4:41 pm on August 20th, 2009:I’m surprised at how many self-professed Marxists say that the LTRPF is somehow flawed, or cannot explain the current outbreak of crises. Marx himself described it as central to his critique of political economy. I can see no other alternate explanations coming forward that even begin to approach an adequate explanation. I’ve seen plenty of Keynesian explanations that blame the lack of regulation, or neo-con orthodoxy.The advent of the microprocessor showed the world that technology in late capitalism was now wiping out more jobs than it would ever create as opposed to earlier technological innovations of capitalist society that caused more new jobs to be created than they eliminated. That is to say, the weight of the constant element of capital hangs so heavily on capitalist production that the only thing a sensible capitalist can do currently is to entirely remove his capital from the messy productive process altogether and achieve profits through what could be called fictitious or speculative capital.Even in my high school when I asked my leftist teacher about the falling rate of profit, which even in the eighties made a great deal of sense in explaining the crisis, the only answer I got was that rates of profit don’t fall, they go up. The trouble with this was that this only took into account the years of post-war prosperity, and conflated this forty year period of relative prosperity in a handful of imperialist powers to a universal constant that “disproved” the Law of Falling Rates of Profit.

A machine will consistently depreciate in value as soon as it is put into production. A commercial CNC board cutting machine, in order to pay for itself must produce a maximum amount of product in order to realize its value. This too causes the value of the machine to depreciate at an even faster rate. A worker can be laid off and rehired at a lower wage. The value of the machine starts to deteriorate through wear and tear from the day it first is put into use in production. I can see this tendency at work, where I work. It isn’t an abstraction. I would argue that it is an observable phenomenon that workers see and experience.

In light of this current outbreak of open crisis within capitalism that the detractors on the left were spectacularly wrong. The collapse of the USSR and the collapse of the US dollar today are a part of the same process in capitalist society, a tendency which has been at work and observable since the early seventies. Having global currency allowed US capital to have what is in essence the largest corporate welfare scam in history-the US dollar itself. This situation is coming to an end as are the post-Marxian certainties of bourgeois economic thought. I’ll never again be able to do anything other than laugh at those who used to tell me that the working class no longer existed or that rates of profit do not fall.

11m said at 8:39 pm on December 21st, 2009:Michel Husson just published on his website 2 papers criticising your study on profitability :http://hussonet.free.fr/histokli.pdfhttp://hussonet.free.fr/h9tprof.pdf

(both in French)

12Mark said at 3:28 pm on April 11th, 2010:Regulations do not fail. They fail when nobody thinks they are needed and therefore they are practically removed. Regulations have to be maintained and improved and checked against practice like you have to do with EVERY LAW in order to ensure its effectiveness.It is nonsense to say that regulation do not work. Total nonsense. The regulators embedded into a political framework DO NOT WORK BECAUSE OF A CONFLICT OF INTEREST. The last report from the new SEC inspector general basically reported that the guys at the SEC are imbecile idiots not capable of doing their jobs (of course, he used other words, but others have already proclaimed that the SEC is full of lawyers missing the practical experience in the finance industry).No one of the officials understands that until now.

To say that regulation don’t work, is to say that anarchy is the best solution. Or don’t you count the rule of law as regulation?

13MHI said at 9:59 pm on May 12th, 2010:A reader in Italy sent this comment:Dear Kliman,I’ve read the article and I found it very good. It explains very well the background of the world economic crisis, going beyond the trivialism we read on the newspapers (“bankers’ greed”, “too much risks” and so on). The idea of many, included Marxist economists, that the crisis is only financial is untenable. The way the crisis manifests itself at the beginning is a financial panic but beneath this there are more fundamental trends at work, as you suggest.

Broadly speaking, the tendency of the profit rate to fall is the main explanation of the crisis as this tendency is how capitalism allows the development of productive forces: mechanization, concentration of capital, labour-saving innovation and so on.

So far so good. Still, I think we need an explanation of how this general, historical, long period trend becomes an actual crisis. How the crisis expresses itself? Trough a colossal piling-up of over-capacity. Every firm tries to resist the tendency of the profit rate to fall by increasing the mass of profits, that is, increasing its production capacity. As anyone follows this road, the overall production capacity grows, thus aggravating the over-capacity problem.

Therefore, your comment that “overproduction and overaccumulation are not explanatory concepts. They are mere tautologies” is ill stated in my opinion. These are a consequence, I would say the main consequence, of how capitalism works. Of course, someone used them to simply explain the crisis (underconsumption, etc) and this is not useful as we know since the debate between Russian populists and Russian Marxists. But in my opinion you exceeded the point.

You suggest, very correctly, that is the destruction of capital, both physical and in terms of value, that allows the profit rate to grow again. I would add another way of depreciation of capital assets that is R&D. When a firm puts on the market an innovation (process or product is the same), implicitly, it forces down the value of installed machines, hence destroying capital assets on the market.

The observations about the link between rate of profit and debts are very acute. I would build more on them. As the rate of profits goes down, so must the interest rate (because of the average rate of profit equalization and other reasons). If we add to this the fact that the more capitalism develops the more indebted is (bourgeois economists call this trend “financial intermediation ratio growth”), the monetary policy is less and less free to set interest rate. That’s why since the 90s the Fed has been forced to keep official rates down. After the crisis erupted, the financial journalists attacked Greenspan, that was their hero until yesterday, because of this policy. Just like Milton Friedman did with the “explanation” of 1929 crisis by means of central bank “mistakes”, this is not science neither history. At the very best it is science-fiction. The problem is much more deep and inescapable for them. Anyway, I think it would be useful to address thoroughly this topic of the monetary policy constriction from a Marxist standpoint.

You rightly criticizes the idea that a “better regulation” (especially in the banking sector) would solve anything. I think it is useful to point out that inasmuch this new regulation is effective it pushes down the profit rate of the banks. So the situation of the banks is the following: profits are coming down (more provisions, less spread and so on), the capital requirements are going up (because of the new regulation), thus the profit rate is attacked on two fronts. The outcome is impossible to hold: banks will find some way to make more profits (that’s why “speculation is back” as some journalist wisely writes). So it is useful to underline how the regulation interacts with the profit rate, hence provoking a cyclical de-regulation trend and so on.

Having said that, keep up with your great work!

Communist greetings,

Lorenzo

Be the first to comment