by Andrew Kliman

Andrew Kliman is the author of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency and The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession.

Traducción al español de A. Sebastián Hdez. Solorza: “La crítica Anti-Marx de Rallo a Marx y la TSSI: Una respuesta”

Introduction

I recently learned that Juan Ramón Rallo, a (right-wing) libertarian economist who lives in Spain, published a two-volume work, Anti-Marx: Crítica a la economía política marxista, in late 2022. The synopsis at the start of the book, and the publicity for it, say that “Rallo tackles the titanic task of reconstructing and, at the same time, destroying Marx’s economic thought. This is the most ambitious critique of Marxism written to date.” A Spanish correspondent has informed me that, because of Rallo’s political orientation, the Spanish media have given his work a lot of exposure and support.

I have not had time to read the whole of this 1600-page work. Given my age and inability to read Spanish without a translator, I probably never will. But I have read enough to respond to a small part of it.

Below, I will address most of what Anti-Marx says about the temporal single-system interpretation of Marx’s value theory (TSSI), an interpretation that defends the internal consistency of the theory. Rallo’s discussion of the TSSI’s defense centers on two issues, the transformation of values into prices of production (the alleged “transformation problem”) and Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory. I will take up these issues in that order, focusing mostly on the former, because Rallo’s discussion of it is quite interesting and illuminating. The foremost reason it is interesting and illuminating is that the actual implications of what he says turn out to be the opposite of his intended ones.

The discussion of the latter issue will be much briefer because there is not much new to say about it. The “Okishio theorem” purported to disprove Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory. TSSI works refuted (disproved) the alleged theorem. Rallo essentially just recycles a very old argument that tries to put the genie back in the bottle, an argument that I and other TSSI authors have already responded to multiple times.

Because so much of my commentary will be critical, I want to begin by pointing out a couple of Anti-Marx’s positive features. First, the title’s truth-in-labeling is most welcome. In marked contrast to most other anti-Marx writers who have discussed Marx’s theories of value and the falling rate of profit, Rallo acknowledges the import of what he writes in a clear and forthright manner. And like the Communist Party of Marx and Engels (not those of Stalin, Mao, …) he disdains to conceal his views and aims. Good show!

Second, Rallo recognizes that, in an exegetical sense, the TSSI is the most successful interpretation of Marx’s value theory, and he disdains to conceal his recognition of this fact:

in the Temporal Single-System Interpretation, all the basic equalities of Marx’s system remain in force. So we can take it as the most faithful interpretation of what Marx probably intended to express without having to presuppose that he incurred contradictions” (vol. 1, section 2).

[While other] criticisms of Okishio’s Theorem are problematic for Marxist economic theory because they link the fall in the general rate of profit, not to the increase in the organic composition of capital itself, but to other factors[, …] the Temporal Single-System Interpretation seems to provide us with a reply to Okishio’s Theorem that does link the reduction in the general rate of profit to the increase in the organic composition of capital … and that also seems broadly [grosso modo] compatible with Marx’s ideas as a whole (vol. 2, section 2).

This departure from the standard practice is also most welcome.

Values and Prices of Production

1. Simple Reproduction and “Solutions” to the “Transformation Problem”

Simple reproduction is Marx’s term for a stationary, zero-growth economy. Each industry produces the same amount of output that it produced previously, using the same amounts of the same inputs.

Rallo claims that simultaneous “solutions to the transformation problem” permit simple reproduction to take place, but that the TSSI is inconsistent with simple reproduction:

the structure of prices of production is incompatible in equilibrium with any structure of values that preserves the labor theory of value and the theory of exploitation. The TSSI is not an economic solution to the transformation problem, but a mere mathematical solution that has the appearance of an economic solution (since it is a mathematical solution that is inconsistent with the economic conditions that would allow the simple reproduction of capital), while the simultaneous solutions to the transformation problem are solutions that preserve macroeconomic equilibrium but at the cost of sacrificing either the labor theory of value or the theory of exploitation. [Vol. 2, section 5.4.1, emphasis in original]

However, it is easy to show that Rallo’s own argumentation leads to the conclusion that the simultaneist “solutions” violate simple reproduction.

This is a tremendously important fact. More than a century ago, Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz purported to prove that Marx’s account of the transformations of values into prices of production violates simple reproduction and is therefore internally inconsistent. If the economy is in a state of simple reproduction when commodities exchange at their values, it will not be in a state of simple reproduction when they instead exchange at their prices of production. To this day, this argument remains the sole “proof” of the internal inconsistency of Marx’s account.

Bortkiewicz then proceeded to “correct” Marx by means of a simultaneist “solution.” He claimed that his solution does permit simple reproduction to take place, both when commodities exchange at their values and when they exchange at their prices of production. Until now, this claim has not been challenged. However, it follows from Rallo’s own argument that Bortkiewicz was incorrect and that his supposed solution fails to correct the alleged internal inconsistency.

Thus, it also follows from Rallo’s argument that, if one rejects any “solution” that is incompatible with simple reproduction, one must reject not only Marx’s account and the TSSI’s defense of it, but also Bortkiewicz’s “correction” as well as every existing and potential simultaneist “solution.” (As I will discuss below, both Marx’s account and the TSSI defense are actually compatible with simple reproduction, but only when they aren’t misinterpreted in the manner of Bortkiewicz, Rallo, and adherents of dual-system interpretations generally.) Conversely, one can jettison the supposed requirement that the economy be able to preserve the same state of simple reproduction whether commodities exchange at their values or at their prices of production. But then, it is not only simultaneist “solutions” that are immune to the simple-reproduction line of criticism; Marx’s account and the TSSI defense are immune as well.

2. Rallo’s Input Substitution Argument

To support his claim that the TSSI is “inconsistent with … simple reproduction,” Rallo takes from neoclassical economic theory the concept of input substitution. Some production processes do not permit input substitution; they require that inputs be used in fixed proportions. For example, one truck and one driver are needed to make ten deliveries, two trucks and two drivers are needed to make twenty deliveries, and so on. However, Rallo is certainly correct that other production processes do permit some degree of input substitution. For example, a firm that produces ten dresses, using thirty yards of fabric and employing seven pattern-cutting workers, might instead conserve on fabric by ordering the workers to slow down and cut more carefully, in which case it may use only twenty yards of fabric but hire an eighth worker. If the firm wants to maximize its profit, it will choose whichever method is cheaper.

But which is the cheaper method? That depends on the price of fabric and the workers’ wage rate. If the price of fabric or the wage rate changes (or both change), the method that costs less may change as well, in which case a profit-maximizing firm will engage in input substitution.

Thus, as Rallo correctly points out, one is “adopting an enormously restrictive assumption” if one assumes “that the means of production and labor power … can only be used in fixed proportions …. and that, therefore, a change in their relative prices does not induce capitalists to alter the organic composition of capital” (vol. 2, section 5.4.1). But if we abandon this restrictive assumption, we must also abandon the idea that a state of simple reproduction can be preserved when relative prices change, as he also correctly points out. Wherever input substitution is possible, “capitalists should not limit themselves to reproducing the same previous productive relations at the new input prices, but should use less intensively the input that has become more expensive and more intensively the input that has become cheaper” (ibid.).

For example, given a sufficiently large rise in the price of fabric, dress-making firms like the one discussed above will switch to production methods that use less fabric but require more workers. Consequently, demand for fabric will fall, so the output of the fabric-producing industry will have to contract. Employment of pattern-cutting workers, and thus the wages paid to them, will increase, which will likely result in increased demand for consumption goods in general and in growth of the industries that produce them.

So far, so good. But at this point, Rallo makes a fatal error that sinks his “titanic … destr[uction of] Marx’s economic thought.”

3. How Simultaneist “Solutions” Involve Changes in Prices

The error is that Rallo confuses changes in prices with temporally determined prices. By “temporally determined prices,” I mean output prices that can differ from input prices. Prices of goods and services that are produced as outputs, at the end of a period, are not forced to equal the prices that these kinds of goods and services had, at the start of the period, when they were employed as inputs. In Marx’s theory and the TSSI, prices are temporally determined; output prices (including prices of production) equal input prices only in exceptional cases.

But if input and output prices differ, prices change during the period. If firms are profit-maximizing and inputs of at least some production processes are substitutable, firms will change their mix of inputs in response to the price changes. Simple reproduction will therefore not take place.

Rallo sees this, but it is all he sees. He fails to see that prices also change in simultaneist “solutions” to the “transformation problem.” He presumably reasoned as follows: in these “solutions,” prices are determined simultaneously, not temporally—output prices are forced to equal input prices—so the prices do not change.

That line of reasoning is incorrect. When (mis)conceived as Bortkiewicz, Rallo, et al. conceive it, the transformation of values into prices of production is a shift from a system in which goods exchange at their values to a system in which they exchange at their prices of production. This shift is itself a change in prices. Thus, if the economy would be in a state of simple reproduction in one of these systems of exchange, it cannot be in a state of simple reproduction in the other, given profit-maximizing behavior and input substitution.[1]

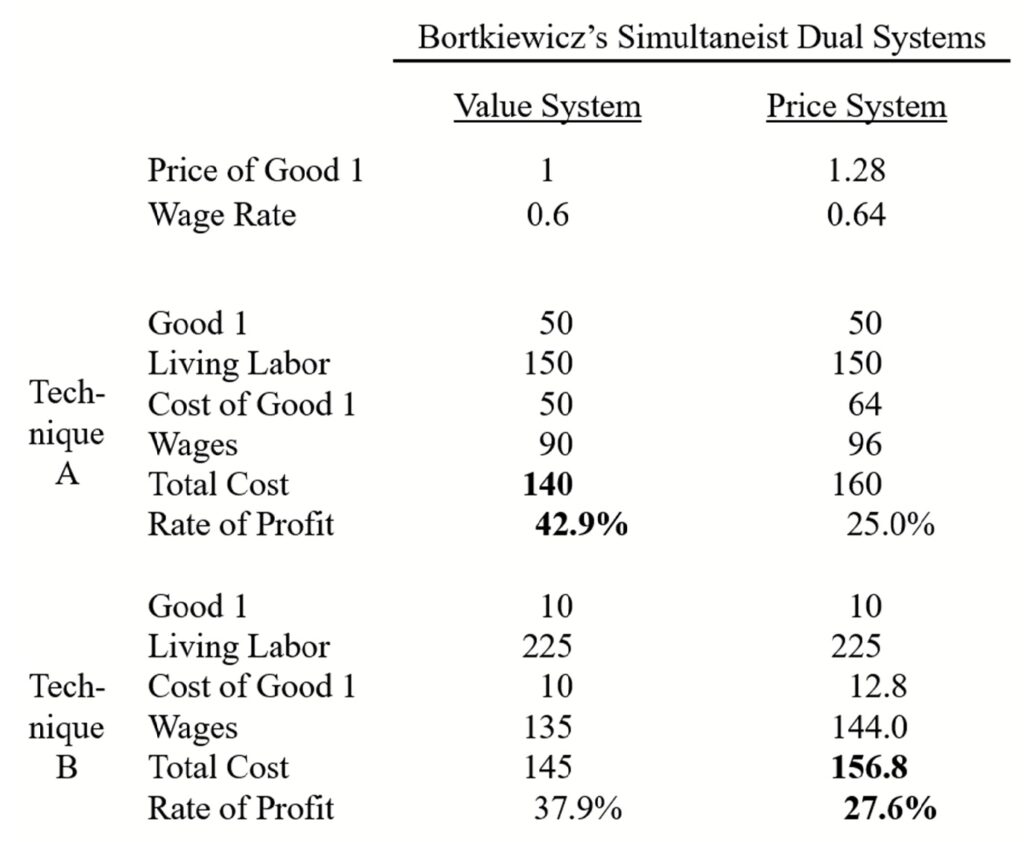

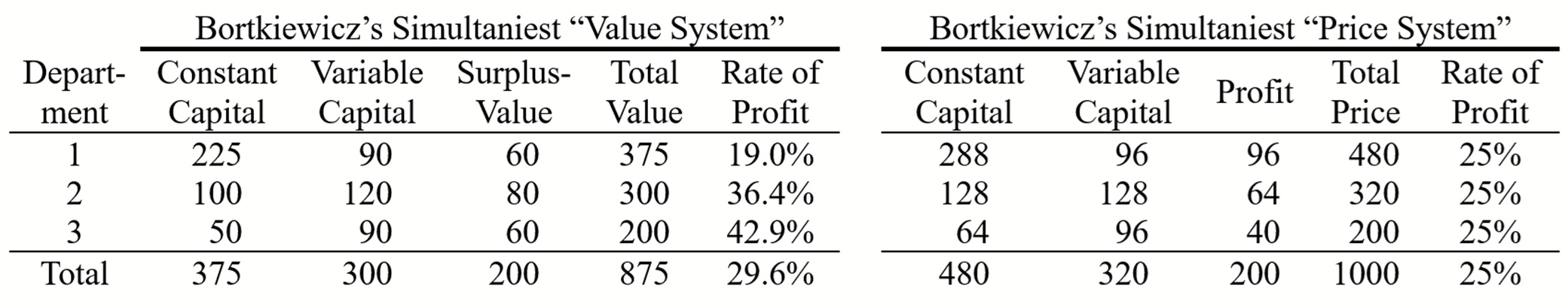

This conclusion holds true universally, but to help illustrate it, let us consider Bortkiewicz’s own example, which Rallo works through in detail (see Table 1). Assume for simplicity that the physical amount of output produced in each department equals the total value of its output. Then, in the “value system,” each good’s simultaneously determined per-unit price (or value) equals 1 (375/375 = 1, 300/300 = 1, 200/200 = 1). ln the “price system” the per-unit prices are 480/375 = 1.28, 320/300 = 1.06 and 200/200 = 1. Also assume, for simplicity, that the amount of labor employed in each department is the sum of the variable capital and surplus-value of its “value system” (e.g., 90 + 60 = 150). The amounts of labor are the same in both “systems,” since Bortkiewicz assumes that both “systems” are in the same state of simple reproduction. Given these assumptions, the (uniform) wage rate, variable capital per unit of living labor, is 300/500 = 0.6 in the “value system” and 320/500 = 0.64 in the “price system.”[2]

Table 1. Simple Reproduction in the Dual “Systems”

Now assume as well that input substitution is possible in Department 3. Two different production techniques are possible, A and B (see Table 2). In Bortkiewicz’s example, Technique A is the technique that firms in Department 3 employ; to produce 200 units of Good 3, they use 50 units of Good 1 and 150 units of living labor as inputs. Technique B is much more labor-intensive; to produce the 200 units of Good 3, only 10 units of Good 1 but 225 units of labor are needed.

Table 2. Input Substitution in Department 3

Given the simultaneously determined prices and wage rate of the “value system,” Technique A is cheaper and, accordingly, Department 3’s firms obtain a higher rate of profit by employing it than they would obtain by employing Technique B. But the shift to the “price system” causes the price of Good 1 to rise in relation to the wage rate. (They both rise, but the rise in the price of Good 1 is far greater in percentage terms.) The profit-maximizing firms of Department 3 respond to this change in relative prices in the manner that Rallo recommends; they “use less intensively the input that has become more expensive and more intensively the input that has become cheaper.” That is, they switch to the more labor-intensive technique, Technique B, which has replaced Technique A as the technique that minimizes their costs and maximizes their rate of profit.

But as a result, the “price system” is no longer in equilibrium in any sense. The prices of the products are not prices of production, since the rate of profit is no longer equalized. Department 3’s rate of profit is 27.6%, while the rate of profit of the other two departments is 25%. Or, more precisely, these would be the rates of profit if supplies of the products continued to equal the demands for them, which they do not. After the switch to Technique B, Department 3 uses much less Good 1 as an input, so demand for Good 1 falls short of supply, and it hires many more workers, which causes demand for the “wage good,” Good 2, to exceed the supply of it. Furthermore, the drop in Department 1’s sales causes a substantial amount of profit to go unrealized. As a result, demand for the “luxury good,” Good 3, falls short of supply as well.

Owing to these imbalances between supplies and demands, the economy is no longer in a state of simple reproduction. “We have thus proved that we would involve ourselves in internal contradictions by deducing prices from values in the way in which this is done by [Bortkiewicz],” once his procedure is improved by adding on Rallo’s additional requirements that capitalists maximize profit and that input substitution is possible.[3]

Given these additional requirements, Paul Sweezy—another “anti-Marx” author and ardent devotee of Bortkiewicz’s “solution”—was quite wrong to argue that

[i]f the procedure used in transforming values into prices is to be considered satisfactory, it must not result in a disruption of the conditions of Simple Reproduction. Going from value calculation to price calculation has no connection with the question [of] whether the economic system as a whole is stationary or expanding. It should be possible to make the transition without prejudicing this question one way or the other. [Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development, p. 114].

As we have just seen, going from value calculation to price calculation has everything to do with the question of whether the economic system as a whole is stationary or expanding in some industries while others are crisis-ridden. Given Rallo’s additional requirements, which are completely reasonable, it is impossible to make the transition “without prejudicing this question one way or the other.”

What this means is that the conception of the transformation of values into prices of production as a transition from a system of exchanges at values to a system of exchanges at price of production—a conception that Rallo has acquired from Bortkiewicz, Sweezy, and many others—is a non-starter. It is a self-contradictory misconception. Given profit-maximizing behavior and input substitution, no such transition is possible. If supplies equal demands when goods and services exchange at their values, they will not remain equal when exchanges take place at prices that deviate from values. But if supplies and demands are unequal when these prices prevail, they are not prices of production.[4]

4. Marx’s Actual Concept of Prices of Production

Yet there is an entirely different conception of the transformation of values into prices of production that remains viable—Marx’s conception. He understood the “formation of the general rate of profit” to be one thing and the “equalization of the general rate of profit” to be a different thing. In Capital, volume 3, they are dealt with separately, the former in chapter 9 and the latter in chapter 10. Accordingly, the formation of prices of production is one thing, while exchanges at prices of production that equalize rates of profit is a different thing. In other words, prices of production always exist, whether or not commodities exchange at these prices.

In what senses do they exist? First, a commodity’s price of production exists as a concept in the minds of capitalists and economists. This concept expresses their ideological view of how “normal” prices and profits are determined, a view that differs greatly from Marx’s in several ways. For instance, whereas Marx held that profit is the monetary expression of the surplus labor pumped out of workers in capitalist production, the standard view expressed by the concept of “price of production” neither explains how profit arises nor how its magnitude is determined; it simply takes for granted both that profit exists and that “normal” prices include an average (but undetermined) amount of profit.

Second, prices of production exist as a benchmark, a measure of success. Since a firm would obtain an average rate of profit if it were to sell its product at its price of production, it can measure how successful it has been by comparing its actual sales price to the price of production. Third, prices of production exist as targets, minimum prices that firms need to realize. To remain viable in the long run, a firm must obtain at least the average rate of profit and thus sell its products at a price that at least equals the price of production.

Finally, and most importantly in the present context, prices of production exist as the long-run average (average over time) of the actual (market) prices that fluctuate around them. A commodity’s actual price rises above the price of production when demand exceeds supply, falls below it when supply exceeds demand, and equals it when supply and demand are in equilibrium.

Rallo seems not to recognize that prices of production exist even when commodities do not exchange at these prices. At the start of his discussion of the TSSI’s defense of Marx’s “transformation” account (vol. 2, section 5.4.1), he writes: “prices of production … can only occur [sólo podrán darse] within an economy that is itself in equilibrium …. The concept of a long-term equilibrium price is meaningless within the framework of an economy that is not in equilibrium.”

In other words, he is suggesting that the concept of long-run average price is meaningless whenever commodities do not exchange at their long-run average prices because supplies and demands are not in equilibrium. This is rather like saying that the concept of average family size is meaningless whenever there is no family of average size! In the US, average family size in 2022 was 3.13 persons. Since the Census Bureau does not count body parts stored in freezers, but only whole living people,[5] there were no families that consisted of exactly 3.13 persons. Nonetheless, that was the average family size. I don’t think it is a meaningless figure at all. Neither does the Census Bureau.

In any case, once one understands Marx’s concept of price of production properly, as the average over time of the prices that fluctuate around it, it is clear that these prices always exist. And given the data that Marx used when illustrating their formation—capital investments, components of cost prices, and surplus-values—together with his theory of how the economy-wide average rate of profit is determined, prices of production can always be computed, whether goods are sold at these prices or at different ones. The computations always lead to the conclusions that total profit equals total surplus-value and that the economy-wide total price of all industries’ products equals their total value.[6]

Note that the data that Marx employed in his computations are enormously different from the data with which Bortkiewicz and all other simultaneist theorists begin. There is no assumption that simple reproduction takes place. Physical input-output relations are not among the data, nor are physical quantities of any inputs or outputs. Marx does not force input prices to equal subsequent output prices.

The reason none of these things are among his data is that they are irrelevant, given his concept of prices of production and his theory of what determines their magnitudes. To compute these prices, we only need to know the period’s capital investments, components of cost prices, and surplus-values. We do not need to know the input-output relations, physical quantities, or input prices. As long as they are compatible with the data that Marx does employ, their magnitudes can be anything at all, and changes in their magnitudes do not affect Marx’s computations or his theoretical conclusions.[7]

In short, Marx’s procedure is entirely general. It does not rely on any restrictive assumptions whatever.

5. Equilibrium of Supply and Demand

This does not mean that prices of production exist independently of the economy’s physical structure. A commodity’s price can only be a price of production if the quantities of the commodity that are supplied and demanded at that price are equal. The point is rather that supply-demand equality is satisfied without imposing any restrictive assumptions.

Marx’s concept of price of production is such that price of production, average rate of profit, and supply-demand equality all imply one another: if an industry’s product sells at its price of production, the industry’s rate of profit equals the economy-wide average rate, and the amount of its product that is demanded equals the amount supplied.[8] Thus, if we consider a hypothetical situation in which all commodities exchange at their prices of production, we are considering a situation in which imbalances between the amounts supplied and the amounts demanded have already been eliminated, by means of changes in prices and changes in supply and demand.

When I say that the imbalances have already been eliminated, I may seem to be assuming what needs to be proven, but I am not. Economists are accustomed to thinking that the quantities of a good that are demanded and supplied can be in equilibrium only at one specific price. So it might seem that proof is needed that Marx’s price of production is that specific price. That is not the case.

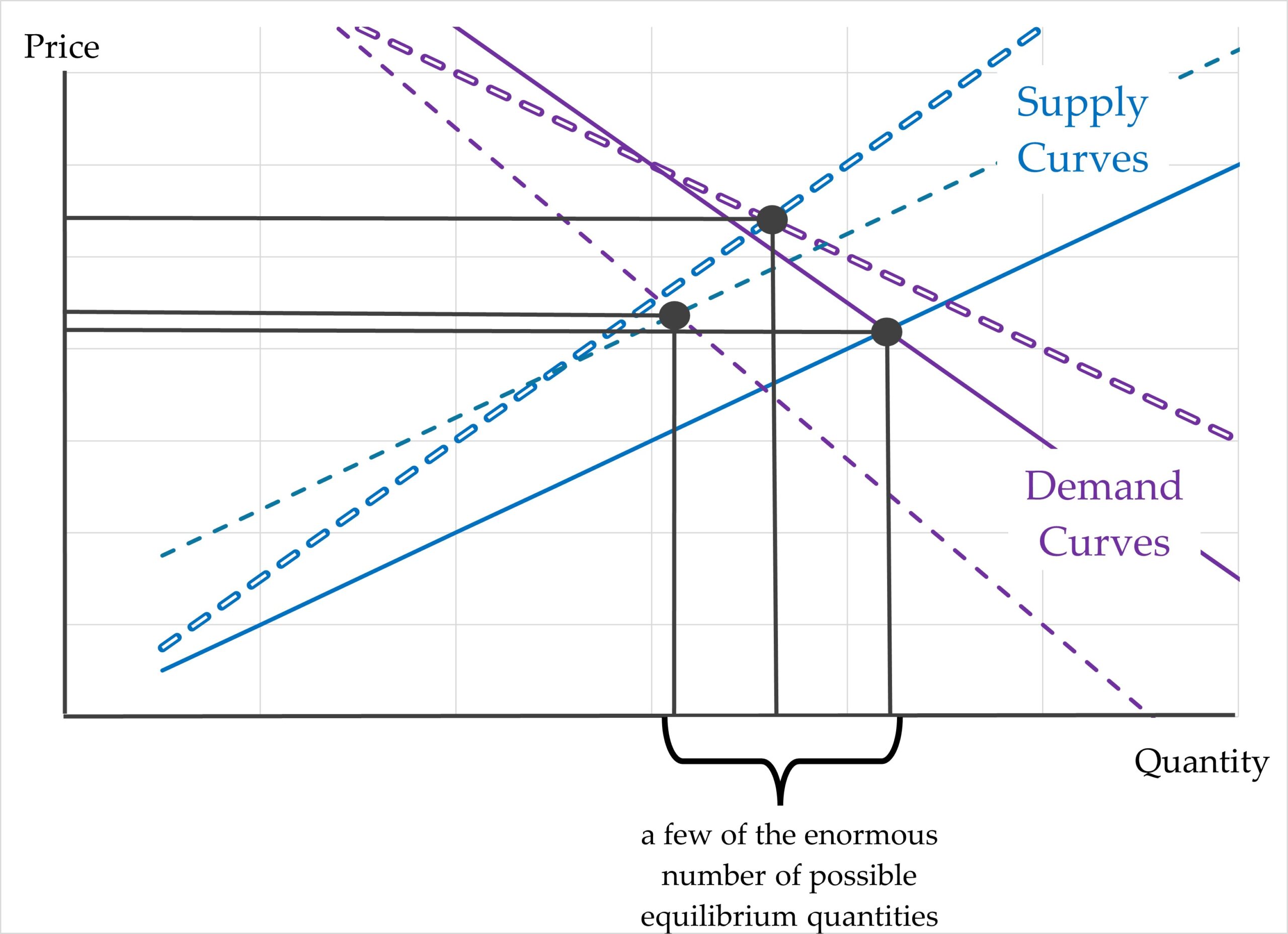

The notion of a unique equilibrium price applies only when economic conditions remain unchanged, so that supply and demand curves remain unchanged as well. Here, however, we are dealing with changing economic conditions. When the price of an industry’s product changes in response to excess supply or demand, this affects other industries as well as consumers. They respond to the price change, and their responses cause shifts in the supply and demand curves of the industry in question. As these curves shift, so does the price that equilibrates the amounts of the product that are supplied and demanded. Hence, there is no longer a unique equilibrium price. Every price that corresponds to the realization of the average rate of profit and supply-demand equilibrium is a “correct” price of production.

In light of the enormous number of shifts in the supply and demand curves that are possible, the “correct” price of production could be almost any price, and the equilibrium quantity of the product could be almost any quantity. More precisely, they could be almost any price and quantity if we allow the supply and demand curves to shift in response to changes in the product’s price and if we allow the quantities supplied and demanded to equilibrate when their actual price equals the price of production (see Figure 1). In other words, almost any price-quantity combination could be the equilibrium state if we refrain from imposing additional restrictions on the price and the quantity. The most common additional restriction is the demand that the equilibrium state be a state in which the future is precisely like the past in some specific respect (e.g., the demand that simple reproduction occurs, or that growth is balanced, or that input-output relations not change, or that prices remain stationary), in addition to being a state in which supply and demand are in equilibrium.

Figure 1

There are two main senses of “equilibrium”—a state of balance and a state of rest. In Marx’s conception, prices of production are “equilibrium prices” in the sense that they are state-of-balance prices; at these prices, the quantities supplied and demanded are in balance. But these “equilibrium prices” need not be, and in general are not, state-of-rest prices. Equalization of rates of profit and supply-demand equilibrium do not require stationary prices (i.e., input prices that equal output prices), or simple reproduction, or any similar state of rest. Indeed, such conditions may well be incompatible with equality of rates of profit and supply-demand equilibrium. (As we saw above, the simple reproduction of Bortkiewicz’s economy is incompatible with them, given profit-maximizing behavior and input substitution.) These conditions are the opposite of requirements; they are additional and unnecessary restrictions, if not barriers. Prices of production, in Marx’s meaning of the term, do not need to satisfy any such restriction.

6. Prices of Production and Marx’s Value Theory

Although Marx’s “transformation” account does not rely on any restrictive assumptions, there are some things it does rely on: his value theory, his theory of the origin of profit, and his demonstration (in chapter 5 of volume 1 of Capital) that the exchange process cannot alter the total amount of value in existence. Given these premises, the level of the general (economy-wide average) rate of profit is not affected by the fact that individual industries receive amounts of profit that differ from the amounts of surplus-value they generate. The same economy-wide total amount of surplus-value is simply being distributed differently. In his “transformation” account, Marx was therefore able to use data with which he began—total surplus-value and total capital investment—to compute the general rate of profit, and then to use the general rate to compute industries’ prices of production and profits. The key results of his computations were the aggregate equalities he obtained: in the economy as a whole, total profit equals total surplus-value and the total price of products equals their total value.

This was Marx’s answer to the standard conception of “price of production” or “normal prices,” which recognized that such prices are the sum of production costs and an average profit, but which failed to explain either how that profit arises or how its magnitude is determined. Marx’s account explained both things, on the basis of his value theory and his theory that the surplus labor extracted from workers is the exclusive source of profit.

The import of his aggregate equalities is that the real-world phenomenon that seem to contradict his theories of value and profit do not actually contradict them. It is true that the prices of individual industries’ products differ from their values, and that these industries’ profits differ from the amounts of surplus-value they generate by extracting surplus labor from workers. But the equality of total price and total value, together with the equality of total profit and total surplus-value, signify that these real-world facts do not contradict Marx’s theories once we understand the theories properly, as theories that pertain to the aggregate economy.

Given the tremendous importance of the aggregate equalities, it is not surprising that an anti-Marx writer like Rallo tries to destroy them, and to do so titanically. He certainly does not succeed.

In section 5.3.5 of the second volume of his book, Rallo tries to disprove the idea of Marx’s that generates the aggregate equalities, the idea “that the law of value determines the general rate of profit.” His argument makes no sense. By modifying a few numbers in Bortkiewicz’s alleged “correction” of Marx’s account of the transformation, Rallo shows that the general rate of profit in Bortkiewicz’s “price system” can change even though the general rate of profit in Bortkiewicz’s “value system” remains unchanged.

So what? The only thing this proves is that the law of value does not determine the general rate of profit of Bortkiewicz’s “price system,” a fact that was already extremely well-known, since it was trumpeted by Bortkiewicz himself. It proves nothing whatsoever about the general rate of profit of Marx’s own theory, which is quite different from Bortkiewicz’s—conceptually different and determined in a different manner. Since Rallo’s argument fails to deal with Marx’s general rate of profit, it also fails to show that the law of value does not determine this general rate or that Marx erred when using it to compute prices of production.

The most charitable way to characterize Rallo’s attempt to disprove Marx here is to say that it begs the question (engages in petitio principii). He begins with Bortkiewicz’s model, a model that assumes that Marx was wrong (as Bortkiewicz’s term “correction” makes clear),[9] and then uses it to “prove” that Marx was wrong.

But it is much worse than that. As we have seen, if the economy would be in a state of simple reproduction if commodities exchanged at their values, as Bortkiewicz and Rallo assume, it cannot be in that state of simple reproduction if commodities instead exchange at prices of production (given profit-maximizing behavior and input substitution). Hence, the general rates of profit in Bortkiewicz’s “price system” and in Rallo’s modified version of it are bogus. These rates of profit presuppose that all departments are able to sell everything they produce, but that is not the case, since the disruption of simple reproduction causes demand for some goods to fall short of supply. So Rallo’s demonstration that two bogosities are unequal to one another although the “value system’s” rate of profit remains unchanged is rather meaningless.

Yet even though Rallo tries to destroy the aggregate equalities, he also expresses what seems to be a very different view elsewhere in his book, as I noted at the start of this article. In volume 1, section 5.2, he writes that

in the Temporal Single-System Interpretation, all the basic equalities of Marx’s system remain in force. So we can take it as the most faithful interpretation of what Marx probably intended to express without having to presuppose that he incurred contradictions. … production prices are anchored to values (which continue to regulate the relations of production and exchange in capitalist economies).

Thus, Rallo concedes that the TSSI preserves Marx’s aggregate equalities, that this implies that “values … continue to regulate the relations of production and exchange” and enables us to understand Marx’s “transformation” account “without having to presuppose that he incurred contradictions,” and that, for these reasons, the TSSI is “the most faithful interpretation” of the probable intended meaning of Marx’s account.

How can we reconcile this forthright and gracious acknowledgment with Rallo’s overall effort to destroy the aggregate equalities? How can we reconcile it with his attempt to demonstrate the falsity of the premise that generates these equalities, the premise that the law of value determines the general rate of profit?

I am not sure. The only hypothesis that comes to mind is that Rallo thinks that he hasn’t really conceded anything, since he goes on to demolish the TSSI. When all is said and done, the TSSI’s preservation of the aggregate equalities, and its ability to eliminate the apparent internal inconsistency in Marx’s account of the transformation, do not matter, because he has demonstrated that “[t]he TSSI “is not an economic solution to the transformation problem, but a mere mathematical solution that has the appearance of an economic solution (since it is a mathematical solution that is inconsistent with the economic conditions that would allow the simple reproduction of capital)” (vol. 2, section 5.4.1, emphasis in original).

But he does not demolish the TSSI, not at all. There are several reasons why he doesn’t.

First, Rallo concedes that the TSSI is consistent with simple reproduction if we do not also require that firms maximize profits and that input substitution is possible. “[T]he process described by the TSSI could only provide us with a possible macroeconomic equilibrium by adopting an enormously restrictive assumption: that the means of production and labor power … can only be used in fixed proportions” (vol. 2, section 5.4.1). Second, since Bortkiewicz himself did not require profit maximization or the possibility of input substitution, Rallo implicitly concedes that TSSI authors have disproven Bortkiewicz’s original “proof” that Marx’s transformation account violates simple reproduction and is therefore internally inconsistent.

Third, we have already seen that Rallo’s conception of the value-price transformation is a self-contradictory misconception. The “problem” he poses simply does not have an “economic solution.” Given profit-maximizing behavior, input substitution, and an economy that would be in a state of simple reproduction if commodities exchanged at their values, there are simply no prices that differ from values, whether temporally or simultaneously determined, that are compatible with that state of simple reproduction. It would be fatuous to require that we solve a “problem” that has no solution.

Finally, as we have also seen, neither Marx nor the TSSI conceive of the formation of prices of production as a shift from a system of exchanges at values to a system of exchanges at prices of production.[10] They do not start from exchanges at values, nor do they conflate the formation of prices of production with exchanges at prices of production. Given this alternative conception, Marx’s account as well as the TSSI’s defense of it are perfectly “consistent with the economic conditions that would allow the simple reproduction of capital,” even when inputs are substitutable and firms maximize profits. Simple reproduction might occur because exchanges take place at prices that differ from the prices of production that nevertheless exist. Simple reproduction might also take place when commodities exchange at their prices of production. That would be the case if both input and output prices happened to equal these prices of production. There is nothing in Marx’s theory or the TSSI that requires such equality of input and output prices. But nothing precludes it either, although it is quite implausible, as is simple reproduction.

I noted earlier that Rallo acknowledges that the TSSI, “the most faithful interpretation,” preserves Marx’s aggregate equalities in an internally consistent manner, and thereby shows that real-world phenomena are compatible with Marx’s view that value relations regulate capitalist production and exchange. Since Rallo’s attempt to demolish the TSSI fails, these are not meaningless concessions about a “mere mathematical solution” but meaningful concessions about a genuine “economic solution.”

On Okishio’s “Theorem” and the Burden of Proof

In section 6.2 of the second volume of his book, Rallo defends “Okishio’s theorem” against the TSSI refutation of it. As he notes, the supposed theorem asserts that “the increase in the organic composition of capital will never reduce the general rate of profit as long as the real wage remains constant.” That claim is significant because it directly contradicts Marx’s law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit (LTFRP).

Marx repeatedly called his LTFRP the “most important law” of political economy. It is very important for several reasons, including political ones. It helps to account for capitalism’s recurrent economic crises, and it helps to explain why these crises are unavoidable: there is a necessary drive within capitalism to continually boost productivity, but the increases in productivity necessarily tend to depress the rate of profit, which in turn tends to reduce new capital investment and to make financial crises both more likely and more severe. Crisis-free capitalism is an impossibility, because the falling tendency of the rate of profit is rooted in aspects of capitalism that the system cannot eliminate—the production of value and the tendency to boost productivity by replacing workers with machines.

Numerous TSSI works have demonstrated that Okishio’s “theorem” is not really a theorem, since it is false. Yet owing to the great political importance of the LTFRP, a never-ending slew of anti-Marx writers have tried and tried again to defend the “theorem” against the TSSI refutation. Rallo is just the most recent (I hope!) one of them. He differs from most of the others in that he acknowledges the anti-Marx character of his work forthrightly. But in terms of content, his effort to put the genie back in the bottle is same old, same old. The writers who have tried (and failed) to defend Okishio’s “theorem” ran out of arguments long ago, so they recycle old ones. The argument that Rallo recycles is the very old argument that the “theorem” isn’t really a theorem about Marx’s rate of profit (see pp. 135-136 of my Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency).

In Table 6.17, Rallo provides a modified version of a numerical example I employed in Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital” (pp. 120ff). Labor-saving, productivity-increasing technical change takes place continually. Employment of means of production increases more rapidly than employment of workers, so the organic composition of capital continually increases. The real (i.e., physical) wage rate remains constant. The result is that the general rate of profit falls, continually—under conditions in which Okishio’s “theorem” asserts that it cannot. Hence, the “theorem” is false.

Rallo understands the results of his computations—“we can see that the increase in the organic composition of capital lowers the general rate of profit.” But (surprise, surprise) he is not satisfied: “In light of the results of Table 6.17, Okishio’s Theorem would seem to be refuted by the TSSI. However, let us realize that what the TSSI actually does to refute Okishio’s Theorem is to estimate a general rate of profit different from that estimated by Okishio’s Theorem itself” (first emphasis added).

What he means by “different” is that Okishio and his followers compute a static-equilibrium rate of profit; that is, they compute what the rate of profit would equal if the prices of outputs that emerge from production were equal to the prices that the same kinds of items had earlier, when they entered the production process as inputs. Here, however, the economic situation is different. The economy is never in a static-equilibrium state. The continual increases in productivity cause the commodities’ values, and thus their prices, to continually decline, which means that output prices are continually lower than the earlier input prices. My computations, and Rallo’s, take account of this fact. Using the actual prices, we compute the actual rate of profit, not the inapplicable static-equilibrium rate,

So the difference in question is a difference between right and wrong. The Okishian rate of profit is wrong because it is inconsistent with the data. My rate of profit, and Rallo’s, are right because they are computed on the basis of the data. Okishio’s “theorem” is false because the prices used to compute its rate of profit are bogus. It’s that simple.

However, Rallo would have us believe that Okishio defined the rate of profit of his “theorem” as a static-equilibrium rate: “Okishio’s Theorem defined the general rate of profit as the value that allows the equilibrium prices of inputs and outputs to be equalized intratemporally (in each period t).” That claim is false. The relevant writings of Okishio and Roemer contain no such definition. They contain formulas for computing the rate of profit in which input and output prices are equal, which is not the same thing. “The definition of a math object is given by … listing properties that the object is required to have” (https://abstractmath.org/MM/MMDefs.htm ) Formulas are not lists of required properties.

Shortly before presenting the example that Rallo uses and modifies, I noted that the static-equilibrium character of Okishio’s rate of profit “is a conclusion of the theorem, not a premise”—something that he and Roemer claimed to deduce, not something they stipulated—and I explained why it is not a premise (Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital,” p. 118). Rallo is undoubtedly aware of my explanation, but he fails to respond to it.

There is another, deeper, reason it is wrong—scientifically, logically, and ethically—to say that Okishio defined the rate of profit as a static-equilibrium rate: doing so illicitly shifts the burden of proof. His “theorem” is a claim about Marx’s rate of profit, a claim that the LTFRP is incorrect. Okishio therefore bore the burden of proving that the rate of profit as defined by Marx cannot fall because of labor-saving technical change. That is what he tried to prove and claimed to prove: “our conclusions are negative to [the] Marxian Gesetz des tendeziellen Falls der Profitrate [law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit]” (p. 95 of Nobuo Okishio, Technical Changes and the Rate of Profit, Kobe University Economic Review 7 (1961), p. 85–99). And it goes without saying that Marx himself never “defined the general rate of profit as the value that allows the equilibrium prices of inputs and outputs to be equalized intratemporally (in each period t).”[11]

For the same reason, when TSSI authors disprove Okishio’s “theorem,” we do not bear the burden of proving that the falling rate of profit we exhibit conforms to Rallo’s or anyone else’s preferred definition of “rate of profit.” Nor do we bear the burden of proving that the falling rate of profit we exhibit has the static-equilibrium character that Okishio’s rate has. Since the “theorem” is about Marx’s rate of profit, so are the TSSI refutations of it. We bear the burden of proving that the rate of profit as defined by Marx can fall under conditions in which the “theorem” claims that it cannot. We have proven this again and again. Rallo’s own computations confirm that we have done so.

When Rallo and the rest of the anti-Marx crowd claim that TSSI authors have not disproven the “theorem,” they also bear a burden of proof. Since both the “theorem” and the refutations of it are about Marx’s rate of profit, the anti-Marx authors bear the burden of proving that the refutations fail to demonstrate that the rate of profit as defined by Marx can fall under conditions in which the “theorem” claims that it cannot. Rallo does not prove this, nor has any other anti-Marx author. Nor will any of them be able to do so. Rallo’s conclusion, that “the TSSI does not refute Okishio’s Theorem,” is thus completely unsubstantiated and meritless.

Rallo does not even try to prove what he needs to prove. Instead, he launches into a long discussion of the fact that Marx’s rate of profit (as understood by the TSSI) would converge on Okishio’s rate if productivity were to stop increasing forever.[12] That discussion is not about the matter at hand, namely whether Okishio’s purported theorem is true or false. In other words, it is not about whether Marx’s rate of profit can fall under conditions in which the “theorem” claims that it cannot—labor-saving, productivity-enhancing technical change being one of those conditions. It is about whether the rate of profit will fall under contrary conditions.

I have emphasized that Okishio’s “theorem” is about Marx’s rate of profit. What does Rallo say about this? Well, he plays fast and loose. It is about Marx’s rate of profit when that position suits his purpose (demolition of the LTFRP). It is not about Marx’s rate of profit when this opposite position suits his purpose (rescuing the “theorem” from the TSSI refutation of it).

Twelve years ago, in an exposé of an almost identical stratagem, I wrote:

[Robin Hahnel’s argument] is an equivocal argument. Now that the disproofs of Okishio’s theorem have become more widely known, attempts to defend it in this manner have become common. Yet equivocation––using the same term in different senses within the same argument––is a logical error; it renders the argument invalid.

In the present case, Hahnel appealed to what we may call OT1, a theorem about real-world capitalism that supposedly shows that “labor-saving, capital-using technical change does nothing, in-and-of itself, to depress the rate of profit in capitalism.” But after this claim was questioned, he appealed to what we may call OT2, a purely mathematical theorem. “The Okishio theorem is a mathematical theorem [which] does not contain any logical flaws” and which is therefore a true theorem––even if its assumptions are “inappropriate” (at variance with real-world capitalism) and even if “someone” wrongly interprets this purely mathematical theorem as a demonstration that labor-saving, capital-using technical change does nothing, in-and-of itself, to depress the rate of profit in capitalism.

Once we have distinguished OT1 from OT2, it becomes clear that “the” Okishio theorem can do no damage to the LTFRP or to the idea that capitalism contains internal contradictions. OT1, the theorem about capitalism, does no damage because it is false: Okishio failed to prove that it is impossible for the equilibrium rate of profit to fall under the conditions he assumed, because he failed to prove that the mathematical object that cannot fall, which he called “the rate of profit,” is the same thing as the equilibrium rate of profit of real-world capitalism or the LTFRP. (It is not the same thing as either of them.) OT2, the disinterested exercise in applied mathematics, does no damage because its “rate of profit” is only a mathematical object, not the rate of profit of real-world capitalism or Marx’s law. [The Failure of Capitalist Production, pp. 107-108]

As a libertarian, Rallo wants to be free to choose. I have no desire to restrict that freedom. So, Dr. Rallo, what will it be, OT1 or OT2? It’s your choice. I only insist that you can’t have it both ways. Taking liberties with logic is taking liberty a bit too far.

Notes

[1] In all dual-system “solutions,” if simple reproduction of the “value system” is assumed, the “price system” will violate simple reproduction. In simultaneous single-system “solutions,” such as that of Moseley, there is no distinct “value system,” but the outputs’ values still differ from their prices of production. If simple reproduction occurs when goods exchange at the prices of production, it would not occur if they instead exchanged at their values.

[2] Although the wage rate changes in money terms, the “real” (physical) wage rate is the same. Workers consume (only) the products of Department 2, so the real wage rate is equal to the money wage rate divided by the price of Good 2, which is 0.6/1 = 0.6 in the “value system” and 0.64/1.06 = 0.6 in the “price system.”

[3] The quoted words appear on p. 9 of Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz, “Value and Price in the Marxian System”; internally contradictory author altered.

[4] Part of what Marx meant by a commodity’s price of production is its average price, i.e., the price around which its actual price fluctuates as demand exceeds supply or supply exceeds demand. This implies that the commodity’s price equals its price of production when supply and demand for it are equal.

[5] Or homo sapiens gavagai, as Quine might have put it.

[6] A commodity’s value equals its cost price plus surplus value; according to Marx’s theory, its price of production equals its cost price plus average profit, where average profit is the economy-wide total surplus-value times the industry’s share of the economy-wide total capital investment.

[7] Some values of these variables are incompatible with Marx’s data, such as input prices that all equal zero or zero physical output in some industry, but such cases are isolated (and weird) exceptions.

[8] The intuition behind this conception is the following. Assume that all industries initially obtain the average rate of profit and that demand for each industry’s product equals the supply. Now imagine that demand for some industries’ products rises, or that supply of these products falls. Their prices will then rise, causing these industries’ rates of profit to rise above the average rate. Their above-average profitability will attract capital investment into these industries. Supplies of their products will thus increase, reducing the excess demand for them and depressing the products’ prices and the industries’ rates of profit. If we instead imagine that demand for some industries’ products falls, or that supply of these products rises, we will have the mirror image of this dynamic: falling prices, below-average rates of profit, a flight of capital investment, and falling supplies of these products that reduce the excess supplies of them and that raise their prices as well as these industries’ rate of profit. The influx and outflow of capital investment will continue as long as there continue to be excess demands and supplies, and thus differences in rates of profit across industries. But if one imbalance is completely eliminated, then so is the other, in which case the influx and outflow of capital investment will cease.

[9] Bortkiewicz’s model does not prove or attempt to prove that Marx was wrong; it presupposes that he was wrong. Bortkiewicz presented the model only after claiming to prove, in an earlier part of his work, that Marx’s own transformation account is internally contradictory (“We have thus proved that we would involve ourselves in internal contradictions by deducing prices from values in the way in which this is done by Marx” (p. 9)). The model is therefore an alternative to Marx’s account—it “deduces prices from values” in a radically different way. Bortkiewicz called it a correction because it assumes the validity of his prior demonstration of “internal contradictions.” But he actually failed to prove that Marx’s account is internally contradictory—even Rallo does not dispute the fact that, given Bortkiewicz’s stated premises, simple reproduction and supply-demand equality are achievable at Marx’s prices of production—so there is nothing to correct.

[10] It is unclear to me whether Rallo fully understands that the TSSI is a single-system interpretation rather than an iterative “solution” to the alleged transformation problem. His discussion of this matter (vol. 1, section 5.2) is quite ambiguous. In contrast to single-system interpretations, but like other dual-system “solutions,” iterative “solutions” wrongly take the term “value of constant capital” to mean the value of the means of production and wrongly take the term “value of variable capital” to mean the value of the means of subsistence (wage goods). Beginning with these values, they arrive at dual-system prices of production step by step. The TSSI does not do so. TSSI authors have produced special-case examples that do so, but “[s]olely in order to facilitate comparison with ‘transformation problem’ ‘solutions’” (Kliman and McGlone 1988, p. 72, emphasis in original). The TSSI itself does not conflate the value of invested capital with the value of its material elements, and its prices of production are always those that Marx would have computed, given the same data. These prices of production almost always differ from dual-system ones.

[11] Except in the imaginary volume √-1 of Capital.

[12] It is interesting that an author so scrupulously concerned with the realism of assumptions about technology when it comes to input substitution is so blithely unconcerned with the realism of assumptions about technology when it comes to rising productivity. Perhaps his actual concern is just to destroy Marx titanically, by any means necessary?

Editor’s note, September 4, 2024: the translation of “la estructura de precios de producción” (“the structure of prices of production”) has been corrected. Before being corrected, it was rendered as “the price structure of production.”

What is a bogosity? Is this a typo? In the 8th paragraph of part 6, there is this sentence:

> So Rallo’s demonstration that two bogosities are unequal to one another although the “value system’s” rate of profit remains unchanged is rather meaningless.

I have trouble following everything that is going on here, but I don’t have Rallo’s text to compare and contrast. However, I’m thinking that maybe this is supposed to say, “Rallo’s demonstration that two price rates of profit are unequal” instead, referring to Rallo’s demonstration that Bortkiewicz’s price system can have a changing rate of profit (hence, two unequal rates of profit) while his value system’s rate of profit remains unchanged. But what I am certain of is that “bogosities” is not right!

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/bogosity

2. (humorous, countable) Something that is bogus.

Wait, nevermind that last comment, I get it now. A “bogosity” is a bogus entity — a bit of bogus matter. This word is used to refer to the Bortkiewiczian price-system general rates of profit, because the Bortkiewiczian interpretation of prices of production implies a disruption of the balance of supply and demand, and “if supplies and demands are unequal when these prices prevail, they are not prices of production.” My mistake, that is perfectly clear.

Dear professor Kliman,

I recently noticed a new article on the refutation of Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. I am very interested in what you think about this text:

https://links.org.au/marx-was-wrong-about-declining-rate-profit-isnt-it-time-we-put-false-idea-rest#footnoteref1_-6dOACtPDms7fW05O-6jQE4MXSu8Z3StujdKa2FsU_nqhC4bvBc60A

Best regards