In this article: Descriptions of the book (in English and Spanish); video of the editor’s presentation on the book (in Spanish); Kliman’s introduction to the book (original English text)

by MHI

¿Forma valor o sustancia valor? Debate sobre ‘El Capital’ de Marx has just been published by Editorial Ande, a Peruvian publisher. The main text is a translated collection of contributions by Andrew Kliman and Fred Moseley, written during a four-year-long (2016-2019) debate between them. The book also includes three introductory pieces—one by each of the authors, and one by A. Sebastián Hernandez Solorza, the editor and co-translator.

Spanish translations of nine Excel spreadsheet files that accompany contributions to the debate can be downloaded from the book’s webpage on the publisher’s site. The book can also be purchased there, for 50 Peruvian Soles, approximately $13.30.

Almost all of Kliman’s contributions first appeared (in English) here, in With Sober Senses. Most of them were part of what became a 13-part series, “All Value-Form, No Value-Substance: Comments on Moseley’s New Book.”

Below are:

- The official description of the book (in Spanish).

- A video of Sebastián Hernandez’s presentation on the book in an August 26 event at the Universidad Nacional de San Marcos in Lima.

- The English text of Kliman’s introduction to the book, which is published here for the first time.

Descripción

Fred Moseley & Andrew Kliman. “¿Forma valor o sustancia valor? Debate sobre ‘El Capital’ de Marx”. Compilado por A. Sebastián Hdez. Solorza. Editorial Ande. Lima, agosto, 2024.

El presente libro compila artículos de un debate sostenido durante 4 años por los reconocidos marxólogos Andrew Kliman y Fred Moseley. El libro gira en torno a la teoría del valor que Karl Marx desarrolla en el tomo I de El Capital y la transformación de valores en precios propia del tomo III de El Capital. De esta forma, en el debate se discutirá en torno al método lógico de Marx, las diferencias entre su teoría del valor y de la tasa de ganancia y la de Piero Sraffa, las críticas de Ladislaus Bortkiewicz y Paul Sweezy, entre otras cuestiones. A decir de Kliman y Moseley, lo que está en juego en este debate es el método lógico de Marx y la comprensión de su obra como una totalidad política-económica-filosófica.

Este texto es una importante contribución al estudio de la Crítica de la Economía Política de Marx en Perú, así como al análisis y profundización mayor de la obra de Marx.

Video

A. Sebastián Hdez. Solorza, Presentación de libro ¿Forma Valor o Sustancia Valor? Debate entre Andrew Kliman y Fred Moseley

Original English Text of Kliman’s Introduction

I am extremely grateful, and deeply indebted to, A. Sebastián Hernandez Solorza. This book exists because of the impressively patient, careful, and tireless work that Sebastián has done to compile, translate, and edit the individual pieces in it, and to find a publisher for it. It would not exist otherwise. A few years ago, I tried to interest two English-language publishers in publishing the debate contained herein, but failed in both cases.

* * *

There are a lot of economic theories out there––mainstream bourgeois economic theories, non-Marxist heterodox theories, and several theories and approaches that “Marxian economists” advertise as improved (modern, corrected) versions of Marx’s theories of value and the tendency of the rate of profit. The debate contained in this book is ultimately about whether Karl Marx’s own value theory, and his falling-rate-of-profit theory that is rooted in the value theory, will be allowed to exist, in their original forms, as live alternatives to these other theories or approaches.

For far more than a century, critics (including “Marxian economists”) have tried, with great success, to disqualify Marx’s original value theory. They have falsely claimed to have proven that the theory is riddled with internal inconsistencies. Since internally inconsistent arguments cannot possibly be right, his theory must be corrected or rejected; logic demands this.

The persistence of this myth cripples all attempts to return to and further develop Marx’s critique of political economy in its original form. The myth serves as the principal justification for the suppression and “correction” of Marx’s theories of value, profit, and economic crisis. It also facilitates the splintering of Marx’s work, a political-economic-philosophical totality, into a variety of mutually indifferent “Marxian” projects.

Fred Moseley is not one of the critics who promulgates the myth. His intention is not to disqualify Marx’s value theory. Yet claims he makes about the theory unintentionally serve the critics’ aims. Above all, what serves the critics’ aims is Moseley’s claim that prices of production in Marx’s theory are such that the per-unit prices of inputs and outputs must be equal.[1] For this reason, I have felt duty-bound to challenge and disprove this and related claims.

But how does the claim that input prices must equal output prices, in Marx’s theory of prices of production, serve the aims of the critics? How does it impede acceptance of Marx’s original theory as a live alternative to the critics’ theories and approaches?

The “internal” inconsistencies that supposedly disqualify Marx’s value theory are actually external––not inconsistencies within the theory, but inconsistencies between the actual theory and particular interpretations of it. These interpretations create the inconsistencies by adding something to Marx’s theory that is not present in the original version. What they add is the condition that input prices must equal output prices.

This extra condition, which people generally (but not Fred Moseley) call “simultaneous valuation,” creates inconsistencies because it necessarily, inevitably, leads to “physicalist” results. Specifically, when one imposes the condition that input and output prices must be equal, the inevitable result is that commodities’ values and relative prices of production, as well as the profits and the rate of profit associated with the prices of production, change when––and only when––there is a change in “physical quantities” (labor, other physical inputs, and workers’ real wages, per unit of physical output). This conclusion contradicts many of Marx’s own conclusions, including some of the most consequential ones, because it is incompatible with the central tenet of his value theory: the tenet that the magnitudes of commodities’ values are determined by the amount of labor needed to produce them.[2]

However, an alternative interpretation of Marx’s value theory, the temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI), eliminates all of the apparent inconsistencies. It eliminates them because it is not physicalist.[3] And it is not physicalist because––and only because––it does not impose the input-price-equals-output-price condition.

Conversely, if one contends, as Moseley does, that Marx himself imposed the input-price-equals-output-price condition on his prices of production, then Marx’s theory was physicalist, and this in turn implies that the actual conclusions of his theory contradict the (non-physicalist) conclusions that Marx himself drew from the theory. In other words, it implies that Marx is indeed guilty of the internal inconsistencies with which he has been charged. This is the principal way in which Moseley’s interpretation unintentionally serves the aims of the critics of Marx’s value theory who seek to disqualify it. Of course, Moseley himself says that Marx was not guilty of these internal inconsistencies, but that is beside the point. The point is that, if Moseley’s interpretation is allowed to become the basis for the conclusion that Marx was not guilty, Marx’s critics can, and undoubtedly will, decisively demolish that line of argument in no time flat, without lifting a finger.

In addition, the very presence of Moseley’s interpretation confuses matters, hindering their resolution and even hindering recognition of what is at issue and what is at stake. Moseley denies that his interpretation saddles Marx with an internally inconsistent theory. He denies this because he also denies that imposition of the input-price-equals-output-price condition leads inevitably to physicalist conclusions. He contends that his interpretation can be anti-physicalist, even though it asserts that input and output prices must be equal, because he has reclaimed “Marx’s logical method.”

This is wrong, dead wrong. I began to work on these issues in the mid-1980s. Well before then, specialists in the field––mainly but not exclusively Sraffians and “Marxian economists”––had already demonstrated that it is dead wrong. (This is why my contributions to this debate display such confidence. It is not confidence in my own thinking, but confidence in collective, time-tested thinking.)

Yet because they lack interest in the present debate, or because they understand how it fits in with their own aims, the specialists have not intervened. And much if not most of the rest of Moseley’s audience seems inclined to take his word regarding the implications of his interpretation, or to conclude that “where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” or that “the truth is somewhere in the middle,” or some similar bit of folk wisdom. As a result, the controversy over the internal consistency of Marx’s value theory seems to be one in which there are multiple “sides” as well as multiple issues––not just simultaneous vs. temporal valuation, which no one cares about, but sexy stuff like Marx’s logical method! And it seems to be a controversy that will not––and perhaps cannot––be resolved.

What gets occluded here are the fact that there is actually only one central issue and the fact that there are only two sides. The issue is the input-price-equals-output-price condition. And the sides are:

Marx himself imposed the input-price-equals-output-price condition.

Thus, his theory actually arrives at physicalist conclusions.

Thus, the theory in its original form is internally inconsistent.

vs.

Marx did not impose the input-price-equals-output-price condition.

Thus, his theory arrives at non-physicalist conclusions.

Thus, the theory in its original form hasn’t been shown to be internally inconsistent.

It’s really that simple. Yet the confusion created by the presence of Moseley’s interpretation makes this difficult to see.

The principal victim of the confusion is Marx. If we think that there are multiple issues and multiple sides, and that the controversy has not been and will not be resolved, what then was Marx’s actual theory? We’ll never know. It could be anything. But if it could be anything, then it isn’t any one thing. In effect, it no longer exists. In this way, those who seek to disqualify Marx’s value theory emerge victorious. Their victory is almost as decisive as it would have been had they proven that the theory is internally inconsistent. Perhaps it is even more decisive.

The rest of us are harmed as well. We are prevented from reclaiming Marx’s Capital. It, too, could be anything because it isn’t any one thing. In addition, because of the endless debate over Marx’s value theory and similar unending controversies, “Marxian economics” can never make any progress. In the absence of norms and procedures that can resolve debates, there can be no progress, especially not when careers and research programs are based on perpetuating unending controversy. As Thomas Kuhn, the famous philosopher and historian of science, stressed, lack of progress in a field and unending controversy over fundamental matters are basically one and the same thing. And it is likely that people of intellectual integrity, insightful, talented people, know to stay away from the field, because it is futile to dedicate one’s working life to doing research when one’s “colleagues,” and thus the public, will never acknowledge that one’s research results are true and have been established to be true.

* * *

In 1934, John Maynard Keynes famously wrote, “In economics you cannot convict your opponent of error; you can only convince him of it.”[4] I agreed with this, but, owing to the considerations I have just outlined, I nonetheless felt it was my duty to try to convict Moseley of error. It was not a task I relished. I did not expect it to go well. At the start of the first installment of my “All Value-Form, No Value-Substance” series, I predicted that my intervention “will prove to be a waste of time and effort.” This prediction was based on two factors. One was that

my efforts to engage with the Marxian economists during the last three decades have consistently been a waste of time and effort. Their primary aim is to hawk their wares—promote their “approaches”—not to get at the truth, resolve outstanding issues, or better understand Marx’s work if a better understanding comes into conflict with their “approaches.”

My prediction was also based on a belief that my effort to set matters straight would fail to get sufficient support from the broader public:

those who have turned to Marx since the Great Recession have, unfortunately, largely imbibed these norms. In some cases, promoting one’s “approach” is conducive to their own careerist aspirations. In other cases, they can’t be bothered trying to force open a genuine debate and trying to ensure that it doesn’t just display wares for them to choose among, but decides outstanding matters. In still other cases, they are just unfamiliar with anything but hawking wares. And there are still more than a few opponents of reason around, postmodernist and otherwise.

Readers of this book will have to judge for themselves, but I think it is hard to deny that Keynes was right and my prediction was right. My attempt to convict Moseley of error failed miserably. I certainly did not obtain acknowledgment from him that the input-price-equals-output-price condition leads inevitably to physicalist conclusions. Nor did my efforts impel the “Marxian economists” or a substantial segment of the broader public to step in and declare that Moseley is in error.

And yet, I think my efforts succeeded admirably, in a different sense. Let me explain.

If a tree falls in the forest, but the tree-worshipers refuse to “hear” the thud, has it made a sound? No, not if the word sound refers to “the sensation perceived by the sense of hearing.” But yes, if the word sound refers to “mechanical radiant energy that is transmitted by longitudinal pressure waves in a material medium (such as air) and is the objective cause of hearing.”[5] The first sense of sound is subjective––it requires that the sensation be perceived––while the latter sense of sound is objective. It pertains to “the objective cause of hearing,” irrespective of whether the sensation is perceived.

“Convict your opponent of error” contains a similar ambiguity. Convict means “to find or prove to be guilty.”[6] But finding that someone is guilty is subjective––a judge or jury or whatever has to recognize that the guilty party is guilty––while proving guilt is an objective matter. If the facts and the proof procedures are adequate, guilt has been proven, irrespective of whether others agree. (If one denies that there is a sense in which guilt and error exist objectively, in the absence of agreement, one needs to accept that juries never acquit guilty parties; that Donald Trump won the 2020 US election, and that COVID-19 is a hoax, if these falsehoods win general acceptance; that, as George Orwell put it, the Party can make two plus two equal five if it wishes––in short, that might makes right.)

If convict is understood subjectively, my efforts to convict Moseley’s interpretation of error failed miserably. Yet if convict is understood objectively, I think I succeeded admirably.

Proving, objectively, that Moseley’s interpretation is guilty of error is all that I can do by myself. What others choose to recognize is beyond my control. And norms and procedures that separate fact from fiction are clearly not in the interests of the “Marxian economists” or the rest of the left academic milieu. The establishment of such norms and procedures will thus require a mass, pro-truth movement that opposes them from the left.

* * *

It is easy to get confused and overwhelmed by all of the minute details discussed in this debate and by all the mathematics. Re-reading the debate now, even I find it difficult to follow the details of the later stages of the debate, which became increasingly focused on secondary matters rather than the main issue. To help readers avoid becoming confused and overwhelmed, I would like to take this opportunity to return to the early history of the debate––long before the contributions in this book were published––when I was able to make my case simply and clearly.

In my 2007 book, Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital,” I employed an extremely simple one-sector example, to illustrate why Moseley and (other) physicalists arrive at the same quantitative results, even though they tell different stories and supposedly start from different “givens.” They arrive at the same results because they all stipulate that input and output prices must be equal. This simple one-sector example illustrated the key points much more clearly than more complicated examples do. The latter add complications, but little more.

So why is this book filled with increasingly complicated examples? The answer is that Moseley kept refusing to accept my simpler ones. First, he refused to accept my one-sector example, claiming in his 2016 book that my conclusion holds true only in the one-sector case. So in the first installment of “All Value-Form, No Value-Substance,” I proved the same thing all over again, but by means of a two-sector example. Moseley proceeded to reject that example as well, claiming that my conclusion holds true only because the example contains only one capital good and only one wage good. I then proved my point a third time, by means of an example in which there are three sectors and two capital goods. That still did not satisfy him. And so the debate continued … to go downhill.

Moseley’s objection notwithstanding, I think readers who are not yet familiar with my one-sector example may find it a helpful introduction to this debate, an example which illuminates the debate’s central issue (must one’s conclusions be physicalist if one imposes the condition that input prices equal output prices?) and which reveals the disguised physicalism of Moseley’s interpretation more clearly than do the more complicated examples I produced later. The following is an abbreviated version of the example that appears on pages 172–174 of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital,” and pages 248–251 of Reivindicando El Capital de Marx.

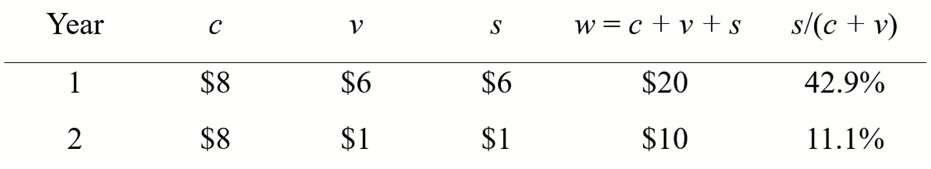

The table below depicts Moseley’s “macro-monetary” interpretation for a single-good economy in two consecutive years. Corn is the only output, produced by means of seed corn and living labor. Farmworkers use their wages to buy corn. Technological change occurs in Year 2: to produce a bushel of corn, only one-sixth as many farmworkers are needed as were needed in Year 1.

Since the same constant capital (c), $8, is “given” in both years, it may seem that Moseley can tell the following story. “In contrast to what occurs in the models of Sraffians and other physicalist theorists, technological progress has caused the rate of profit to fall. The same amount of constant capital is used in both years. But in Year 2, only one-sixth as many workers are needed to produce a bushel of corn as in Year 1, so variable capital (v) falls from $6 to $1; and since the real wage rate is unchanged, Year 2’s surplus-value (s) is also only one-sixth of what it was in Year 1. Thus the rate of profit (s/[c + v]) falls.”

This is a nice story, very Marx-like, but it is the exact opposite of the truth. Although Moseley’s constant capital is supposedly “given,” what has actually taken place is that twice as much seed corn is needed to produce a bushel of corn in Year 2 as was needed in Year 1. And even though the variable capital falls to the same degree that employment falls, the real (i.e. physical) wage rate is not “given” either. It doubles as well. Thus, what causes Moseley’s rate of profit to fall is a combination of technological regress––not progress––and a rise in the real wage rate. In other words, the rate of profit that falls here is the physical rate.

These results can be derived as follows. Because (but only because) Moseley’s inputs and outputs have the same per-unit value or price, his macro-monetary value aggregates can be expressed as

c = λ × (means of production)

v = λ × (real wages)

w = λ × (physical output)

where λ is the per-unit value of corn––both its value as an input and its value as an output––and w is the total value of the corn output. Hence, if we divide c by w, the λ terms in the numerator and denominator cancel out, and we obtain the quantity of the means of production (seed corn) required to produce a unit of physical output. Similarly, if we divide v by w, we obtain workers’ real wages per unit of physical output. Let’s call these fractions a and b, respectively.

In Year 1, a = c/w = $8/$20 = 0.4, but in Year 2, a doubles to $8/$10 = 0.8. Twice as much corn is needed to produce a bushel of corn output. And b = v/w = $6/$20 = 0.3 in Year 1 and $1/$10 = 0.1 in Year 2. So the real wage per bushel of corn output falls to one-third of its original level. But since the amount of labor employed per bushel of corn has fallen to one-sixth of its original level, the real wage rate—real wages per unit of labor––has doubled as well.

It is easy to show that Moseley’s “macro-monetary” rate of profit is the physical rate of profit in disguise, and that the former falls because the latter falls. Moseley’s rate of profit is

But (1 – a – b)/(a + b) is the physical rate of profit in a one-good model. It falls from

(1 – 0.4 – 0.3)/(0.4 + 0.3) = 42.9% in Year 1 to (1 – 0.8 – 0.1)/(0.8 + 0.1) = 11.1% in Year 2.

These results are identical to Moseley’s. The fact that he expresses his rate of profit as the ratio of surplus-value to capital-value advanced, instead of as a ratio of physical coefficients, makes no difference. It is all value-form and no value-substance.

* * *

To conclude, I want to say a few things about the special meaning that the word interpretation has in the context of this debate. I discussed this issue in Part 7 of “All Value-Form, No Value-Substance,” but it may be helpful to understand what interpretation means here before one starts to read this book.

To evaluate the debate contained in this book, I suggest that you take careful note of which claims are accompanied by arguments and proofs, and which claims are merely asserted. And take note of who is arguing and proving, and who is merely asserting. You will notice a striking asymmetry.

Yet the asymmetry may be ever greater than it initially appears to be, because the word interpretation has a special meaning in the context of this debate. Generally speaking, when people say “this is my interpretation”––of some aspect of Marx’s work, or of anything else––we take that at face value. The statement itself is strong, perhaps sufficient, evidence, that this is indeed their interpretation. After all, they know what they think! Their interpretation may be correct or incorrect, but they surely are correct that it is their interpretation. So, in general, the statement “this is my interpretation” does not need to be supported by a proof or other argument.

In the context of the present debate, however, Moseley can be wrong about the content of his interpretation of Marx. And since he can be wrong, a statement like “this is my interpretation” does need to be supported by a proof or other argument. Here’s why:

In case after case, Moseley says (correctly) that some theoretical conclusion of Marx’s is non-physicalist. But that is only one aspect of his interpretation. The other aspect is that, in the case in question, input prices must equal output prices. Therefore, when Moseley claims that his interpretation is non-physicalist, he can be wrong about the content of his own interpretation, because it may be impossible to arrive at non-physicalist conclusions if one imposes the condition that input and output prices must be equal. Indeed, this is what the whole debate is about.

Thus, Moseley’s claims regarding the content of his interpretation should not be taken at face value. They require proof or other supporting argument. If such support is not provided, the claims can and should be dismissed as mere assertions.

Andrew Kliman

New York City

June 3, 2022

Notes

[1] Moseley contends, for example, that a kilo of coal produced at the end of a period, the output, must have the same price as a kilo of coal that entered production, as an input, at the start of the period. The term inputs refers to the labor and means of production (raw materials, machinery, etc.) that are used in production; the term outputs refers to the products that are then produced. Price of production is Marx’s term for the specific, hypothetical, sale price of a commodity that would allow its producer to obtain a rate of profit that is just equal to the economy-wide average rate of profit. If all commodities were to sell at their prices of production, the rate of profit would be equalized throughout the economy.

[2] See chapter 5 of Andrew Kliman, Reivindicando El Capital de Marx: Una refutación del mito de su incoherencia (Barcelona: El Viejo Topo, 2020), or the original, English-language edition, Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007).

[3] This is a necessary condition, not a sufficient condition. To eliminate the apparent inconsistencies, Marx’s value theory must also be interpreted as a “single-system” theory, in which commodities’ values and price, although distinct, are determined interdependently, not a “dual-system” theory in which values are determined in a “value system” while prices are determined in a separate and discordant “price system.”

[4] Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, vol. 13, Donald Moggridge (ed.); London: Macmillan, 1973, p. 470, emphases in original. Quoted in Timothy Taylor, “You Cannot Convict Your Opponent of Error; You Can Only Convince Him Of It,” BBN Times website, March 1, 2019, https://www.bbntimes.com/global-economy/you-cannot-convict-your-opponent-of-error-you-can-only-convince-him-of-it .

[5] The quoted phrases are definitions 1(b) and 1(c) in the first of Merriam-Webster’s entries for sound; accessible at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/sound .

[6] This is definition 1 in the second of Merriam-Webster’s entries for convict; accessible at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/convict .

There is a German translation of Reclaiming Marx’ Capital: Kliman, Andrew (2020), Die Rückgewinnung des Marxschen “Kapital. Eine Widerlegung des Mythos innerer Widersprüchlichkeit Mangroven Verlag. Given the global influence of Michael Heinrichs New Reading of Marx, a reading that destroys Marx’s theory of value, it is important that “Die Rückgewinnnung des Marxschen ‘Kapital'” finds a wider German-speaking audience. Fred Moseley just published Marx’s Theory of Value in Chapter 1 of Capital. A critique of Heinrich’s Value-Form Interpretation. Palgrave. It offers exigetical evidence that Heinrich’s “value creation by exchange” is his own theory, not the theory of Marx.