by Ralph Keller

Editor’s note, August 6, 2024: An article by Andrew Kliman and Ralph Keller, referred to below as “forthcoming,” has now been published. A link to it has been added.

TREATING THE TSSI OF MARX LIKE A DEAD DOG

A RESPONSE TO SETH ACKERMAN’S “ROBERT BRENNER’S UNPROFITABLE THEORY OF GLOBAL STAGNATION”

Introduction

Seth Ackerman’s 2023 article [1] in Jacobin perpetuates the view that Marx’s rate of profit cannot fall because it is logically wrong.[2] He roots his view in the Okishio Theorem, which allegedly disproved Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory. Ackerman thereby ignores and suppresses the temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI) of Marx’s Capital. The TSSI shows that the Okishio Theorem cannot disprove Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory because it is rooted in unviable physicalist-simultaneist reasoning that contradicts Marx’s value theory. Under conditions in which the Okishio Theorem’s physicalist-simultaneist rate of profit must rise, Marx’s rate of profit can fall.[3]

I am confident that Ackerman and others are aware of the TSSI. Fourteen years have passed since Andrew Kliman’s (2007) Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency was published, and there has been a drawn-out debate between the TSSI’s proponents and its critics (e.g., in Potts and Kliman, 2015). Furthermore, Rob Bryer, an emeritus professor of accounting, argued—in 2017 and 2019, and very recently in Radio Free Humanity episode 111—that the rate of profit (and other variables in Marx’s value theory) should be measured in accordance with the TSSI. Yet Ackerman and others choose to treat temporal reasoning like a dead dog, as if it did not exist, and thus they do not evaluate theories in good faith. Indeed, Ackerman admits as much when he writes that “[t]here are further complications relating to current prices versus historical prices” (i.e., simultaneists’ revaluation of past investments versus temporalists’ use of the original figures; see note 2, above), “but I’ll leave those aside.” Ackerman and others therefore continue to present “corrections” as superior versions of Marx.

This situation not only hinders progress towards liberty and freedom from the shackles of capitalism when the debate surrounding Marx could, and should, be much different. In addition, failure to evaluate theories in good faith, in relation to the alternatives, comes with much intellectual baggage attached. Addressing this issue is my motivation for writing this response to Ackerman, and is best expressed by a statement that Henry Hyndman attributed to Marx: “To leave error unrefuted is to encourage intellectual immorality.” I do not wish to carry such baggage.

Left: Karl Marx. Right: Nobuo Okishio (center); clockwise from top left—Seth Ackerman, Doug Henwood, Robert Brenner, Aaron Benanav.

I will begin with a brief discussion of whether Marx’s falling-rate-of profit theory entails that capitalism inevitably tends toward a final breakdown, as well as a brief illustration of the crucial difference between simultaneous-physicalist and temporal interpretations of Marx’s original text. Calling out the dead dog treatment, and the intellectual immorality that comes with it, I will then discuss why Marx’s rate of profit can fall, logically, when read temporally. This part of my response engages with the work that has refuted the Okishio Theorem. I then proceed to a discussion of the empirical evidence. Using Canadian depreciation data, Ackerman produces a skyrocketing “rate of profit” of US businesses since 1985; I explain why this “rate of profit” is bogus. I also show why the rate of profit can indeed fall when calculated temporally, again calling out intellectual immorality and the dead dog treatment of the TSSI by some authors.

The Two Issues at Stake

The first issue at stake in this article is straightforward, namely whether the capitalist system of production necessarily breaks down. Ackerman critiques the view that Marx’s falling rate of profit implies a tendency for capitalism to break down as a falling profit rate reaches critically low levels. Rosa Luxemburg subscribed to the breakdown idea, and Henryk Grossmann’s (1929) book on the subject continues to enjoy a strong following. In my view, however, the idea that capitalism will, eventually, break down is much like wishing for the savior’s return—we’ll be waiting forever and a day.

Andrew Kliman recently published a scientific critique of Grossmann’s breakdown model (Radio Free Humanity Episode 53 also deals with that critique). Kliman showed that the cause of breakdown in Grossmann’s model is not an insufficient mass of profit, but that

the real cause of breakdown (in the model) is a physical imbalance: the total supply of physical output does not grow fast enough to allow productive demand in physical terms (demand for means of production plus good for workers’ consumption) to keep growing at the postulated rate … such a physical imbalance is neither inevitable nor plausible. The tendency of capitalism to head inevitably toward breakdown, which Grossmann claimed to have revealed, is therefore simply fictitious. [emphasis in original]

I therefore agree with Ackerman when he writes that “[t]he tendency of capitalism to head … toward breakdown … is … simply fictitious.” But I strongly disagree with his reasoning. He argues that there is no breakdown tendency because there is no falling rate of profit, i.e., because Marx was wrong.

Ackerman, however, uses what is called simultaneous-physicalist reasoning, not Marx’s reasoning. The simultaneous approach uses replacement costs for new inputs, at the time outputs are sold, to re-value past inputs—hence, today’s outputs and inputs acquired in the past are valued simultaneously. The “rate of profit” that results from this is essentially a relation between physical output and physical input—changes in commodities’ prices and values over time do not affect it. This procedure spirits away parts of the economy’s capital stock, in the denominator of the profit rate calculation, whenever the replacement cost of inputs is less than their original cost.

Later in this article, I will critique Ackerman’s method of calculating the rate of profit, but it may be useful here to illustrate his reasoning using a simplified example of a one-good economy in which corn is the only output and only input (other than labor). Say that 100 bushels of output are produced in Year 1 and sold for $6 per bushel, or $600 in total. All of this output is then bought for $600 and invested as seed corn for Year 2. Labor-saving technical change occurs during Year 2. As productivity rises, the price (or value) of corn falls, so the corn output of Year 2 sells for $4 per bushel. Under simultaneous valuation, the books record $4 x 100 = $400 as capital invested for seed corn in Year 2—instead of the original $600—which spirits away $600 – $400 = $200. And so, when calculating the profit rate, simultaneists’ figure for capital investment is not the original investment of $600, but only $400. “[T]he miracle of simultaneous valuation has caused” 1/3 of the original investment of Year 2 “to disappear” (Kliman, 2007, p. 123).

I think that simultaneism is quite wacky. In contrast, the temporal method of valuation, on which I draw throughout the remainder of this response to Ackerman, uses the original $600, and is thereby consistent with what accountants do (see Bryer, 2017, 2019). The reasoning is called temporal because it leaves the original $600 unchanged when, later, the corn output of Year 2 is sold and new inputs are acquired for subsequent production periods. I will show below that when the rate of profit is calculated temporally, it can fall even as the simultaneist rate rises.

What Marx Argued—and Did Not Argue

Marx demonstrates in chapter 13 of Capital, volume 3 why the rate of profit falls. Yet like many of Marx’s critics, Ackerman does not even hint at Marx’s actual procedure in chapter 13. He instead sidelines Marx’s presentation as “conjecture.” Ackerman draws on Michael Heinrich’s claim, in Monthly Review, that Marx did not prove, a priori, that the rate falls, and that he indeed could not prove its fall. Yet Kliman and colleagues refuted this claim in their response to Heinrich, on the grounds of Capital, volume 3’s original text. Specifically, they demonstrated that Heinrich’s demand for an a priori proof stems from a misunderstanding of what Marx’s theory of the falling profit rate is and is not: it “is not a prediction of what must inevitably happen, but an explanation of what does happen” (emphases in original).

Importantly, they pointed out that “Heinrich himself notes correctly” that Marx treated the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as an established fact. Heinrich wrote that

[t]he idea that the social average rate of profit declines over the long term was considered an empirically confirmed fact since the eighteenth century. Adam Smith and David Ricardo both attempted to demonstrate that the observed fall in the rate of profit was not simply a temporary phenomenon, but rather a result of the inner laws of the development of capitalism. [emphasis added)]

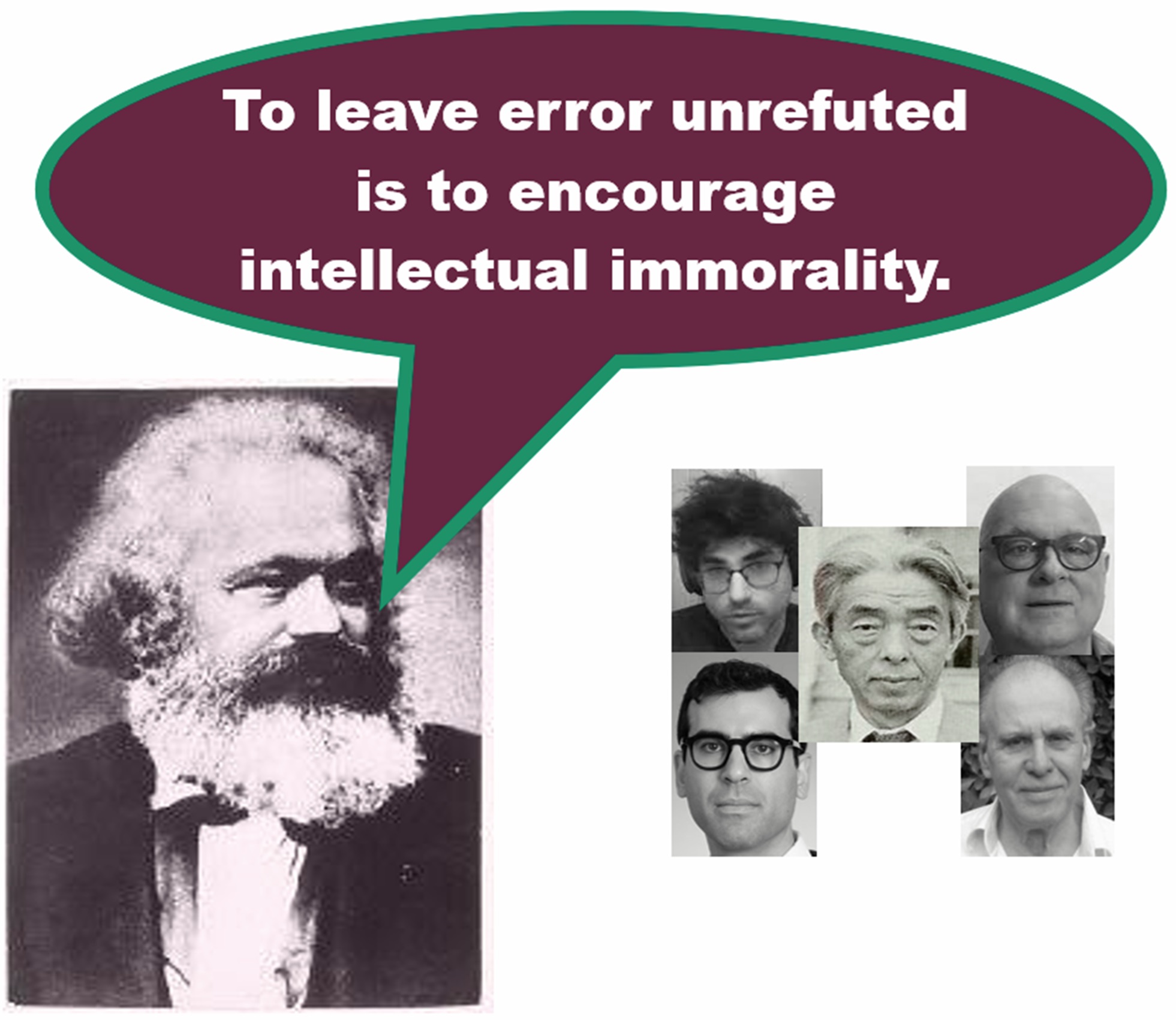

But Smith and Ricardo did not explain, at least not satisfactorily, why the rate of profit falls. To answer this, let us consider Marx’s original presentation of why the profit rate falls (1991, p. 317; online text), with c meaning constant capital (net capital stock + materials); v meaning variable capital (employee compensation); and MROP meaning Marx’s Rate of Profit. For simplicity, Marx assumes a surplus-value (profit) of 100 in the numerator.

This unobjectionable presentation is an if-then argument, rooted in a real-world situation. It does not need to be supplemented with an a priori proof that the rate of profit must fall, come what may, because that is not what Marx is claiming. He is claiming that, if such and such occurs, then the rate of profit must fall.

Yet Marx’s conclusion that the rate of profit will fall in these circumstances is not the “conjecture” that Ackerman alleges it is. This conclusion is clearly deduced from the argument’s premises, not merely conjectured.

The misunderstanding that Marx predicted that the profit rate must fall, come what may, is not exclusive to Heinrich. But it is a misunderstanding nonetheless.

First of all, Marx identified six factors, in chapter 14 of Capital, volume 3, that counteract a fall of the profit rate. One of them is a general reduction of wages. Given the above presentation of why the profit rate tends to fall, the effect of low wages is straightforward to see: if v falls because of lower wages, then the denominator falls and the numerator rises (because surplus-value or profit is assumed to equal 200 – v), which in turn accounts for a rise of the entire rate of profit. The point is that the presence of counteracting factors in Marx’s original text reveals that he does not think that the profit rate must fall, come what may.

But the main issue at stake in this debate is whether the profit rate exhibits a long-term tendency to fall. Ackerman works overtime to sideline this idea, which, he alleges, was ultimately not important even to Marx himself. He begins as follows

There’s … good reason to doubt Marx’s own commitment to the idea. Clearly the FROP [falling rate of profit] was a theory Marx wanted to believe was true. Just as physicists and mathematicians have been known to hope that an especially elegant theory or theorem will end up being confirmed by a future proof or experiment, Marx wanted to find a way to make the FROP work because, within the context of his theory, it led, as Duncan Foley put it in his 1986 Marxian economics textbook, to “a beautiful dialectical denouement.”

But Marx was a scrupulous scholar, and every time he tried to work out the details of the concept in his notes and drafts of the 1850s and 1860s, he found himself—as the German Marxologist Michael Heinrich has shown—lost in a maze of algebra that could only prove that a falling profit rate was a possibility, not a necessary outcome of capitalist development. [emphasis in original]

I beg to differ. Marx did not think that the profit rate must fall in the long run, come what may. His texts contain no such claim. Like Smith and Ricardo, Marx regarded the long-term fall in the profit rate as “an empirically confirmed fact,” as Heinrich himself tells us. This means that the factors that tend to reduce the rate of profit do outweigh the counteracting factors in the long run. It does not mean that it is logically inevitable that they must do, come what may.

Thus, Marx’s analysis requires no a priori proof of any such “necessary outcome” in order to be “complete” or “finished.” Because Marx was explaining why the rate of profit does tend to fall in the long run, not predicting that it must fall, the fact that he did not prove what he did not even assert is not the “failure” that Heinrich and Ackerman would have us believe it is.

When he writes that there is “good reason to doubt Marx’s own commitment” to his falling-rate-of-profit theory, Ackerman is engaging in childish speculation. There is no good reason to doubt Marx’s commitment. In their response to Heinrich, Kliman and colleagues reviewed the textual evidence, which explicitly shows that Marx considered the law correct and finished in a theoretical sense, although he was adamant that it was not ready for the publisher.

But Ackerman ignores their rebuttal of Heinrich, and instead continues undeterred: “as Sweezy noted in 1942, Marx’s analysis in that section was ‘neither systematic nor exhaustive’ and ‘like so much else in Volume III it was left in an unfinished state.’” Huh?! Sweezy is certainly entitled to his view, but having read Capital, volume 3 closely myself, I am just as entitled to disagree: Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit is finished in the theoretical sense.

The manuscripts he left were not ready for publication—the editor of the volume, Frederick Engels, had to undertake some relatively minor condensation, abridgement, and rearrangement to make them publishable—but, contrary to what Heinrich suggested, this certainly does not mean that the theory that appears in volume 3 is Engels’ theory rather than Marx’s. As Kliman and colleagues argued, “[w]hen one condenses, abridges, rearranges, etc., one does not create a theory that was not already there to begin with. One simply makes the theory that is already there more perspicuous.”

However, the childish speculation of Marx’s critics knows no bounds. Ackerman once more:

How central … was the FROP to Marx’s view of capitalism? In Marx’s Theory of Crisis, [Simon] Clarke made a compelling case: “Perhaps the best indication of the importance that Marx attached to the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is that he did not mention it in any of the works published in his lifetime, nor did he give it any further consideration in the twenty years of his life that followed the writing of the manuscript on which Volume Three of Capital is based.”

… Marx had definitively lost interest in it.

I do not consider Clarke’s argument to be “a compelling case,” because—as Marx himself explicitly stated, on multiple occasions—he completed his draft of what became Capital, volume 3 well before the final version of volume 1 was written and published. Once he had resolved a problem, he moved on. I work in the same way. How do Ackerman and other critics of Marx work?

Ackerman published this speculation last year, but Kliman and colleagues had already responded to it a full ten years earlier, in 2013. Ignoring their response does not make him appear particularly competent as a scholar.

Like a Dead Dog: Acting as if the TSSI Did Not Exist

I am confident that Ackerman is aware of the temporal reading of Marx’s original work. But like almost everyone else, including Heinrich, Ackerman has not responded to Kliman and his colleagues. Why not? Why does almost everyone treat the TSSI like a dead dog, suppress it and act as if the TSSI did not exist? I believe the answer is two-fold, namely that they

- have no answer to the TSSI

- prefer the strawman Marx who claimed that the profit rate must fall, come what may

By treating the TSSI like a dead dog, Marx’s critics—in this case, Ackerman—are able to present “corrections” of his theories as superior versions of Marx, and to avoid having to correct their own theories in light of it.

If, instead, they were to treat the TSSI as a live alternative, then the issues under debate and the character of the debate would be completely different. Treating the TSSI like a dead dog is an act of intellectual immorality. Period.

Clockwise from top left: South Dakota governor Kristi Noem; Cricket, Noem’s 14-month-old puppy, whom she killed; Karl Marx; Seth Ackerman.

Photo credits for top images: Jeff Dean/AP/Pavel Rodimov/iStock

Can the Rate of Profit Fall—Logically Speaking?

I noted above that Ackerman does not appear to be particularly competent as a scholar. But being competent may not be his motivation. Instead, his motivation might simply be to perpetuate the view that the rate of profit cannot fall because of labor-saving technical change and higher productivity. Indeed, his thinking along those lines is evident, since he calls into question the possibility of such a fall in the rate of profit. Specifically, Ackerman (like other critics of Marx) asks: why would private enterprises engage in behavior detrimental to their interests?:

The challenge that critics have always put to Marx’s theory is this: Why would any capitalist ever willingly introduce a method of production that yields a profit rate lower than the prevailing one? The profit rate might decline for any number of reasons. But surely the least plausible cause is the one variable over which capitalists have direct, conscious control—the choice of production methods.

Ackerman fails to point out that Marx anticipated this question in Capital, volume 3, answering it as follows:

No capitalist voluntarily applies a new method of production, no matter how much more productive it may be or how much it might raise the rate of surplus-value, if it [the new method] reduces the rate of profit. But every new method of production of this kind makes commodities cheaper. At first, therefore, he can sell them above their price of production, perhaps above their value. He pockets the difference between their cost of production and the market price of the other commodities, which are produced at higher production costs. This is possible because the average socially necessary labour-time required to produce these latter commodities is greater than the labour-time required with the new method of production. His production procedure is ahead of the social average. But competition makes the new procedure universal and subjects it to the general law [of the falling rate of profit].[4] A fall in the profit rate then ensues—firstly perhaps in this sphere of production, and subsequently equalized with the others—a fall that is completely independent of the capitalist’s will. [Marx 1991, p. 373; alternative online translation]

The crux of Marx’s answer is that it is rational—profit-maximizing—for capitalists to innovate, even though the general profit rate eventually falls as a result. The capitalist who introduces the new production method initially enjoys an increase in his profits, since he sells his product at the going market price but produces more cheaply than his competitors. It is also profit-maximizing for the competitors to respond by adopting the new method of production, because doing so reduces their costs of production; they would be worse off if they failed to keep up.

By referring to a question “that critics have always put to Marx’s theory,” but suppressing the fact that Marx himself answered it, Ackerman wrongly makes it seem as though the question is unanswerable (and that Marx was rather stupid and/or incompetent).

Why the Rate of Profit Can Still Fall—Logically Speaking

The Okishio Theorem and its implications

Now we arrive at the heart of the matter, i.e., the question of why Ackerman and other critics of Marx bend over backwards to try to convince their readers that the rate of profit cannot fall because of cost-reducing technical change? The answer is that the Okishio Theorem says that it cannot.[5] Okishio (1961) set out to disprove the final two sentences in Marx’s statement quoted above. That is, he set out to disprove that the post-innovation rate of profit, once “generalized,” can fall. Later, Roemer (1981) presented his own version of Okishio’s theorem, which was also directed against Marx’s “no capitalist voluntarily applies a new method of production” explanation.

The theorem’s essence is that the rate of profit, once “generalized,” cannot fall if capitalists introduce new and improved production methods that boost their own rates of profit. This belief has a long tradition among Marx’s critics, tracing its origin to Russian scholar Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky in an influential 1901 monograph. Ackerman writes that Tugan-Baranovsky reasoned that the capitalist’s “choice of technique” (method of production) must, if anything, have the effect of pushing the rate of profit constantly higher, not lower, as Marx had claimed. After all, an improved production technique improves productivity; that is, it increases a firm’s volume of output with the same or even fewer inputs.

Ackerman then endorses this line of argument and the Okishio Theorem specifically:

In 1961, … Japanese economist Nobuo Okishio published a landmark paper showing that Tugan[-Baranovsky]’s critique of the FROP [falling rate of profit] was, at least, logically correct: at a given set of ruling market prices, and assuming no change in the real wage, any production method that a profit-maximizing capitalist would introduce must have the effect—once it’s been generalized throughout the economy—of raising, rather than lowering, the general profit rate.

This does not mean that the rate of profit cannot fall. The consequence of this line of argument is rather that, if the rate of profit does in fact fall, what causes the fall cannot be cost-reducing, productivity-enhancing, technical innovation. This is the position that Anwar Shaikh and Robert Brenner adopted. They embraced the Okishio Theorem, but they argued that the rate of profit can nonetheless fall when productivity-enhancing technical innovation takes place. What this means is that the rate of profit can fall despite such technical innovation, not because of it. The rate of profit falls because of other factors, that do depress it, and their effect more than offsets the effect of the technical innovations that tend to raise it.

Specifically, Shaikh argued that the rate of profit can fall because sales revenues drop when firms engage in price wars. Similarly, Brenner argued that the rate of profit in the US fell because, starting in the 1970s, manufacturing firms kept the lid on the prices of their products, in response to chronic excess capacity brought about by foreign competition.

Ackerman argues against both of their positions, but these disagreements are not at issue here. What is at issue instead is the centrality of the Okishio Theorem to all sides of that debate. Shaikh and Brenner hold fast to the theorem no less than Ackerman does, and thereby deny that profit rates can fall because of labor-saving technical change.

The dead dog treatment once more

The kicker is that Okishio Theorem is wrong. Okishio did not prove that the rate of profit necessarily rises (or remains constant) as a consequence of cost-reducing technical change, if real wages remain constant. The reason he didn’t prove this is that it isn’t true.

The Okishio Theorem fails because of the simultaneous and physicalist reasoning it employs. It has been disproven by using temporal reasoning. The earliest temporalist refutation of Okishio’s theorem seems to be Murray (1973), which was later followed by Ernst (1982) and Kliman (1988). In addition, using temporal reasoning, Freeman (1998) presented a generalization of the earlier special case that was used to disprove the Okishio Theorem, by

establish[ing] the precise conditions under which the profit rate rises or falls, and establish[ing] the general result that the profit rate necessarily falls as a consequence of capitalist accumulation with a constant real wage, until and unless accumulation ceases in value terms.

In a 1997 paper, “The Okishio Theorem: An Obituary”, Kliman demonstrated (by means of argument and numerical illustration) that the post-innovation profit rate can be lower than the initial rate, and he emphasized that,

[t]o refute the Okishio theorem, … no particular model of technical change and [capital] accumulation is required. What is necessary is that the technical changes be labor-saving, that prices (measured in labor-time) fall when the amount of labor needed to produce the commodities falls, and that the innovations occur in rapid enough succession that convergence of prices towards a stationary state does not occur.

Kliman obtained this result because the prices to which he referred were determined temporally, not simultaneously. He also drew attention to the anti-physicalist character of the result: “contrary to the apparent belief of the proponents of the Okishio theorem …, it is simply not true that the magnitude of the [economy’s] uniform profit rate is uniquely determined by physical input/output coefficients.”

These and other TSSI works disprove the Okishio Theorem on the grounds of its own premises. Since the theorem has itself been refuted, it does not and cannot disprove Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory.

Yet Ackerman hides the fact that the Okishio Theorem is false. He suppresses the demonstrations that disprove the theorem. Because he suppresses them, he is able to act as if neither Marx nor anyone else has explained why capitalists willingly introduce new production methods that lower the rate of profit. Indeed, he is able to act as if no such explanation is possible, because capitalists do not in fact introduce such production methods. He would have us believe that Okishio proved that they do not, and that’s that. Ackerman therefore engages in unscholarly behavior that encourages intellectual immorality.

Empirically, is a Falling Profit Rate a Statistical Mirage?

The simultaneist “rate of profit” never fully recovered after the 1960s, which is the source of Brenner’s stagnationist argument. The temporalist rate of profit never rebounded, during “neoliberalism,” from the fall it experienced as the post-World War II boom came to an end. Ackerman wants to challenge Brenner’s conclusion. By doing so, he is implicitly challenging the conclusion reached by temporalist research as well.

Specifically, Ackerman recalculates the profit rate for the US, because he claims that official US government estimates of depreciation, or fixed-capital consumption, are too low, and that this leads to estimates of the rate of profit that are too low as well. The supposed problem is that the US government’s figures understate the degree of depreciation of capital assets because they overstate the “service lives” of the capital assets. Even small changes in asset service lives can have a huge impact on the measured capital stock: the longer the life of the average capital asset, the more years’ worth of accumulated investment is embodied in the capital stock at a given moment in time, and hence the lower is the measured rate of profit.

Ackerman is correct that, if fixed assets (i.e., fixed constant capital in Marx’s terminology) depreciate more rapidly over time, this will cause the capital stock in the denominator of the rate of profit to grow more slowly. The numerator of the rate of profit (i.e., profit itself) is also affected by how rapidly assets depreciate but, over time, changes in the rate of depreciation have a much stronger effect on the denominator. Thus, if the rate of depreciation rises, the rate of profit will tend to rise over time. (Vice versa, if the rate of depreciation falls, the capital stock will increase more rapidly, and the rate of profit will therefore tend to rise over time.)

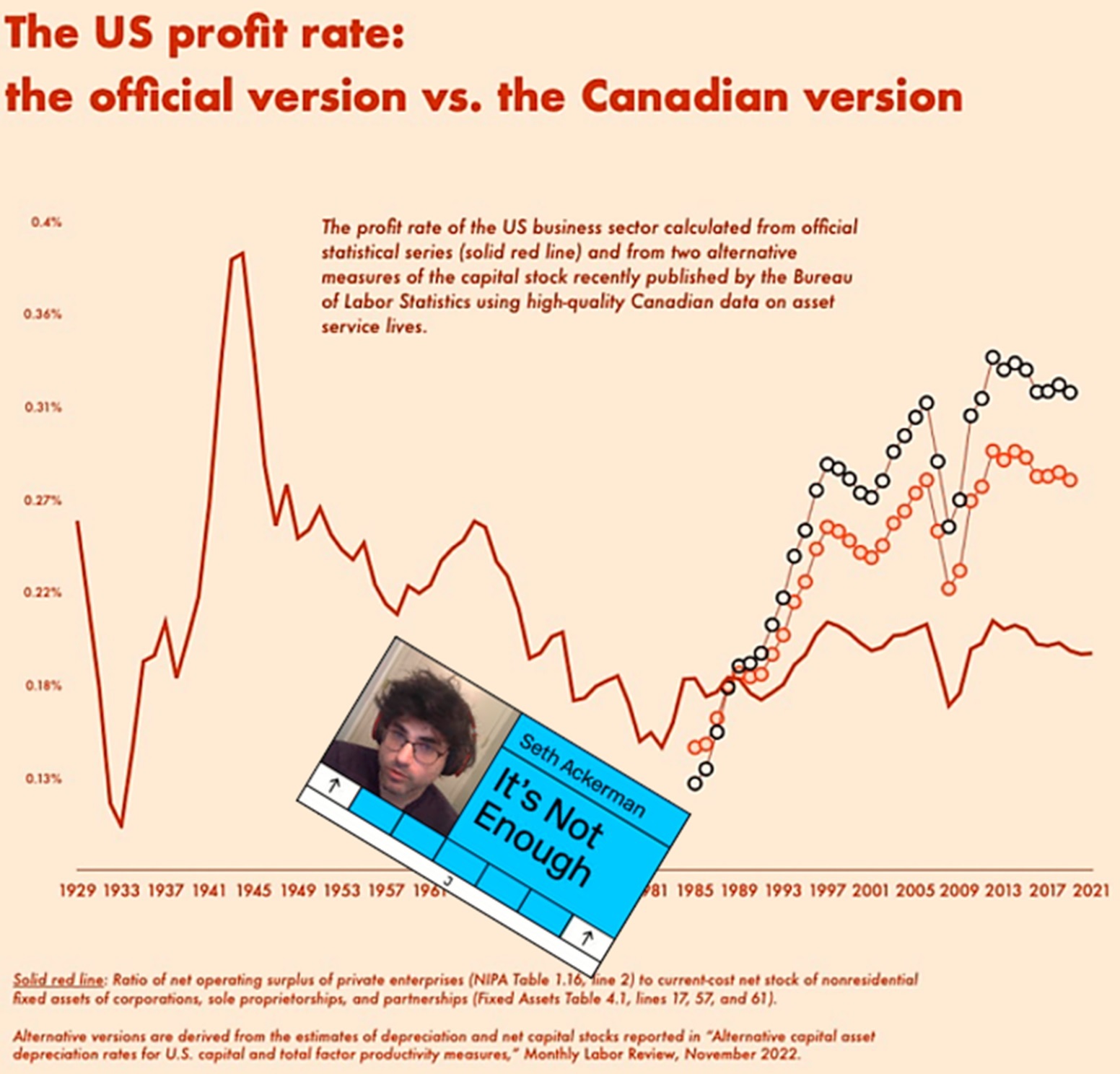

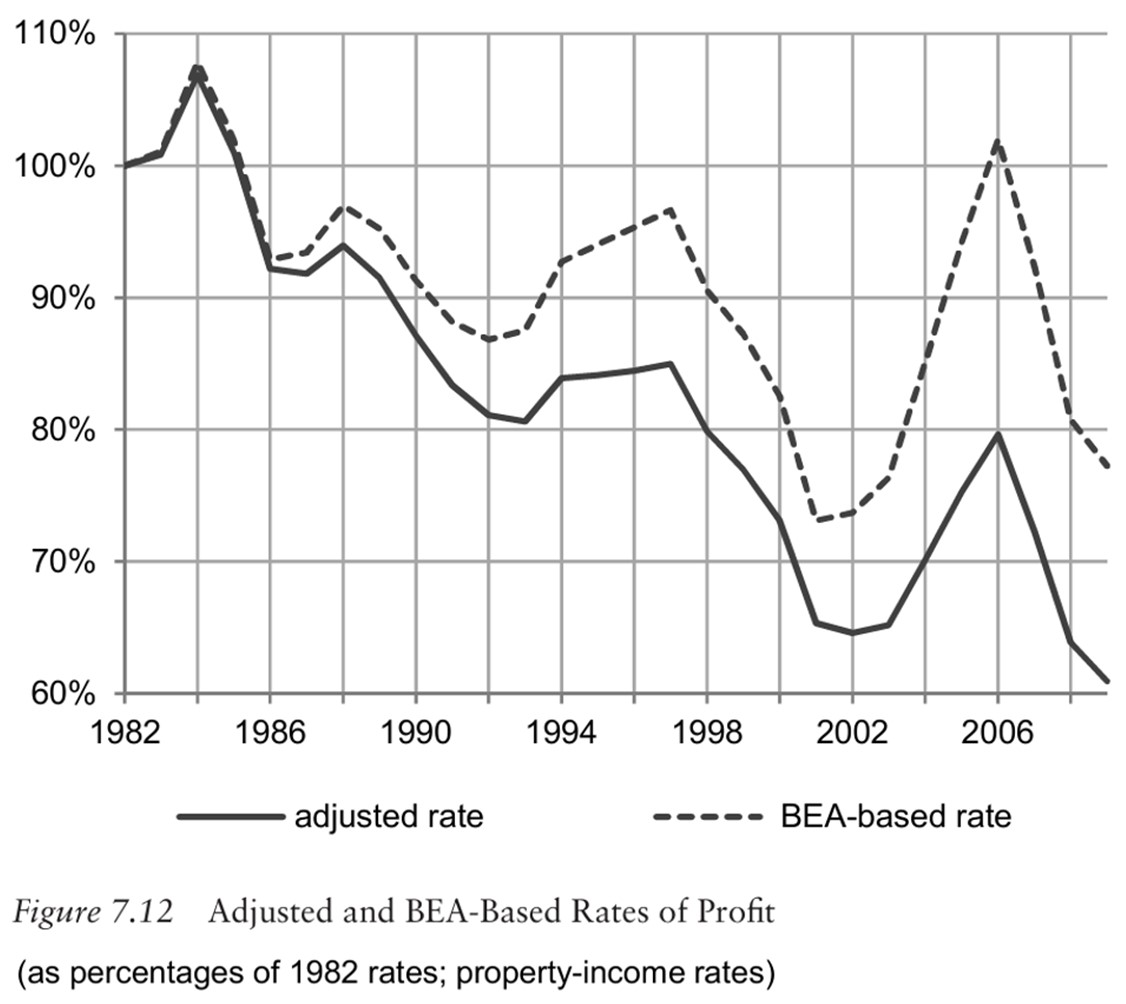

Ackerman recalculates the rate of profit using recent estimates of depreciation and the capital stock in the US private sector that are based on Canadian depreciation rates, which he claims are more reliable than the US government’s official depreciation rates. Ackerman’s revised US rate of profit, shown in his graph below, rises markedly after 1985, the first year of calculations based on Canadian depreciation data. (There are two different sets of re-estimated depreciation and capital-stock figures, and thus two different rates of profit recalculated by Ackerman—the lines with red and black markers).

This graph leads him to conclude that

[t]he unreliability of measured depreciation rates poses a major problem for theories of economic performance based on the premise of falling profit rates because, as it turns out, the decline in measured profit rates since the 1960s is entirely attributable to changes in measured depreciation.

Case closed because a falling profit rate, if researchers find one, is merely a statistical mirage, right? Well, not so fast.

There are two reasons it is wrong for Ackerman to claim that “it turns out [that] the decline in measured profit rates since the 1960s is entirely attributable to changes in measured depreciation.” First, although he claims that the Canadian depreciation rates are more reliable than the official US ones, no such claim was made by the researchers who produced the new depreciation and capital-stock estimates that Ackerman used.

Second, even if the Canadian depreciation rates are, in fact, more reliable, Ackerman’s rising-to-the-skies upturn in profitability after 1985 is bogus, because he egregiously misuses the data. In a forthcoming paper, Andrew Kliman (who correctly guessed that Ackerman had mishandled the data) and I will discuss the problems in detail.

Here, it is sufficient to note that, while a rising depreciation rate leads to a rising rate of profit (this is a question of trend), a higher depreciation rate (i.e., a question of level) does not. In other words, a higher depreciation rate simply leads to a higher rate of profit, not a rising one. The main reason that Ackerman’s post-1985 rising rate(s) of profit are a statistical mirage is not that he used higher (Canadian) depreciation rates, but that his rates of depreciation rise abruptly, starting—you guessed it—in 1985. When we use the higher (Canadian) depreciation rates without introducing an abrupt rise in 1985, the statistical mirage disappears.

But there is another issue as well, one which affects the rate of profit based on official government data as well as Ackerman’s bogus re-estimates of the rate of profit. The issue is “moral depreciation.”

In Capital, Marx makes a distinction between moral and physical depreciation. The latter reflects physical wear and tear and is measured as the amount of value that passes from fixed assets to the product. Moral depreciation is the amount of money owners would lose if they sold a fixed asset today because it has become (relatively) obsolete. Kliman (2012, p. 140) noted in this context that

Marx speaks of “the danger of moral depreciation,” and he argues that because capitalists try to avoid this danger by using up their machines quickly, before they become obsolete, “it is … in the early days of the machine’s life that … [a] special incentive to the prolongation of the working day makes itself felt most acutely” [Marx 1990, p. 528; alternative online translation]

It would be helpful if data-reporting standards allowed us to estimate depreciation due specifically to wear and tear, but official statistics only report total depreciation, due to obsolescence as well as to wear and tear.

Kliman (2012) also noted that, in the US, “there are good reasons to suspect that moral depreciation has increased markedly as a percentage of advanced capital” because depreciation as a whole has increased due to the extensive employment of Information-Processing Equipment and Software (IPE&S), which depreciate particularly quickly. And almost all their loss of value counts as moral depreciation because they do not experience notable physical wear and tear.

Kliman then estimated the reduction of profit due to the rise of moral depreciation for IPE&S: as the depreciation figure reported by the US government’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), minus what this depreciation figure would have been if the economy’s “total depreciation had increased at the same rate as the depreciation of non-IPE&S fixed assets” (p. 144).

As discussed above, changes in depreciation affect both the numerator and the denominator of the rate of profit—that is, both profit and advanced capital—but not to the same extent. Kliman (2012, p. 145) noted that

[m]oral depreciation … reduces both profit and advanced capital as measured by the BEA. … Over time, however, the advanced capital tends to be reduced by a relatively larger amount than profit, because reductions in the net stock of capital, unlike reductions in profit, are cumulative and permanent. The numerator of the BEA-based rate of profit is therefore realized profit (surplus-value minus losses due to moral depreciation), while the denominator is advanced capital minus losses due to moral depreciation.

We cannot know what the rate of profit would have been in the absence of moral depreciation, “because we do not know how much of the depreciation reported by the BEA is moral depreciation.” (ibid). Nevertheless, Kliman’s adjustments allow us to estimate the effect of “increased moral depreciation on the rate of profit” (ibid., emphasis added), as depicted in the following graph.

Kliman’s (2012, p. 147) US rate of profit, non-adjusted vs adjusted for depreciation effects

The BEA-based rate is the actual rate of profit (with capital stock measured at historical cost). Because the BEA treats moral depreciation just like physical depreciation, the movements of the actual rate of profit are driven partly by losses due to obsolescence. The adjusted rate is Kliman’s (2012, p. 147) estimate of what the rate of profit would have been if losses due to obsolescence had not increased: the rate of profit would have fallen significantly further than it actually fell.

The fact that the actual fall in the rate of profit after 1982 was more modest than the fall in the adjusted rate is thus a sign of economic weakness, not a sign of economic strength. The rate of profit was propped up, to a substantial extent, by ongoing losses of capital-value due to obsolescence and moral depreciation.

This is of course the exact opposite of the story that Ackerman wants us to believe, on the basis of his misuse of deprecation data and the mega-boom in the rate of profit that results from this misuse. The profit rate he calculates is a statistical mirage indeed.

Wrapping Up

Theories need to be evaluated in good faith in relation to alternatives. But Ackerman, by invoking the Okishio Theorem, has improperly excluded the TSSI of Marx from good-faith consideration. In other words, by comparing and contrasting alternatives to Marx in a way that excludes and suppresses the TSSI, Ackerman treats Marx like a dead dog. This is not only unscholarly conduct; it also means that Ackerman leaves error unrefuted. Intellectual immorality is a corner difficult to back out of.

If the TSSI were instead treated as a live alternative, then the issues under debate and the character of the debate would be completely different. We would then have a debate that propels us forward, a debate which would support our endeavor of achieving liberty and freedom from the shackles of capitalism.

REFERENCES

Bryer, Robert. (2017). Accounting for Value in Marx’s Capital: The Invisible Hand. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

__________. (2019). Accounting for History in Marx’s Capital: The Missing Link. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Ernst, John R. (1982). Simultaneous Valuation Extirpated: A contribution to the critique of the neo-Ricardian concept of value, Review of Radical Political Economics 14:2, 85–94.

Grossmann, Henryk. (1992). The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System: Being also a theory of crises. Translated and abridged by Jairus Banaji. London: Pluto Press.

Kliman, Andrew J. (1988). The Profit Rate Under Continuous Technological Change, Review of Radical Political Economics 20:2–3, 283–89.

__________. (2007). Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A refutation of the myth of inconsistency. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

__________. (2012). The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession. London: Pluto Press.

Marx, Karl. (1867 [1990]). Capital, Vol. I: The process of production. London: Penguin Books.

__________. (1893 [1991]). Capital, Vol. III: The process of capitalist production as a whole. London: Penguin Books.

Murray, Robin. (1973). Productivity, Organic Composition and the Falling Rate of Profit. Bulletin of the Conference of Socialist Economists, Spring, 53–56.

Okishio, Nobuo. (1961). Technical Changes and the Rate of Profit. Kobe University Economic Review 7, 85–99.

Potts, Nick, and Andrew Kliman, eds. (2015). Was Marx’s Theory of Profit Right? The Simultaneist-Temporalist Debate. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Roemer, John. (1981). Analytical Foundations of Marxian Economic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tugan-Baranovsky, Mikhail. (1901). Studien zur Theorie und Geschichte der Handeslkrisen in England. Jena: G. Fischer.

NOTES

[1] Below, all quotations from Ackerman’s article appear without links. Unless indicated otherwise, all references to Ackerman pertain to that article.

[2] Different authors mean different things by “rate of profit.” By “Marx’s rate of profit,” I mean the rate of profit as he defined it.

[3] The crucial feature of physicalist-simultaneist revisions of Marx is that investments of capital at the beginning of a year, and earlier ones, are revalued at the replacement cost of the physical capital assets at the end of the year. The TSSI denies that investments (as opposed to physical capital assets) are retroactively revalued. This makes Marx’s value theory logically consistent.

[4] By “universal,” Marx means that the capitalist’s competitors keep up with him by adopting the improved production method, which therefore becomes the method of production that is universally employed throughout the economy.

[5] In-depth discussions of the theorem are available in, e.g., Kliman (2007) and Potts & Kliman (2015).

Be the first to comment