by Andrew Kliman

Editor’s Note: This article is the (slightly edited) text of the author’s March 27, 2022 talk at a meeting of Marxist-Humanist Initiative, titled “On Dunayevskaya’s May 1953 Letters on Hegel’s ‘Absolute Idea’ and ‘Absolute Mind.’”

Raya Dunayevskaya’s May 1953 letters on Hegel’s “Absolute Idea” and “Absolute Mind” are of course quite difficult. One thing that tends to make them even more difficult is reading them in light of one’s own concerns rather than the author’s concerns. That might even make understanding the letters worse than difficult; if one’s concerns don’t dovetail sufficiently with her concerns, it may be impossible.

Often, people read these letters in light of their own concerns, not intentionally, but simply because they are not well acquainted with her concerns. Today’s meeting, and the second meeting on the 1953 letters, have been designed to address this problem. We cannot possibly clarify every detail in the two letters during these meetings. The meetings are intended to provide us with means to avoid getting bogged down in their details, by helping us understand better what is most important about these letters and what to focus on. So we are trying to grasp the two letters as a whole, and grasp them in the context of their problematic—the historical, political, and organizational context that Dunayevskaya confronted in 1953, and what she was trying to work out in response.

For these reasons, both meetings will be taking up both letters, and the reading for both meetings include, not only the 1953 letters, but also a few short pieces that help to situate the letters within their historical, political, and organizational context. I’ll be taking up aspects of both letters, and aspects of some of the additional readings, in this presentation.

“Mind” as the New Society

Dunayevskaya’s May 12, 1953 letter is about the final chapter of Hegel’s book Science of Logic, “Absolute Idea.” Her May 20, 1953 letter is about the final chapter of Hegel’s book Philosophy of Mind, “Absolute Mind.” What is “Mind”? Dunayevskaya interprets “Mind” as the new society. This may seem nuts. How can she possibly get from Mind to the new society? Was this just a willful misreading, an effort to politicize a text that is actually about pure philosophy, not politics?

Well, the term translated as “Mind” is Geist, which is often translated as “Spirit.” In the entry for Spirit in his Historical Dictionary of Hegelian Philosophy, John W. Burbidge writes that “Spirit, for Hegel, means self-conscious life, and it applies to the divine as well as the human.” He goes on to say that, in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, “the chapter on spirit describes a kind of knowledge in which members of a community understand and grasp the complexity of their own interaction.” That’s rather similar to what Marx referred to as our “fac[ing] with sober senses [our] real conditions of life, and [our] relations with [our] kind.”

Now note that in Hegel’s Philosophy of Mind, Absolute Mind, or Spirit, is the unity of Subjective Mind and Objective Mind. And the topics he deals with in the Objective Mind section of the book are social institutions––law, morality, the family, civil society, and the state. So the unification of Subjective Mind and Objective Mind can be understood as the self-conscious life of a human community that has overcome the division between its subjective concept––what it is to be human––and the objective reality of its laws, morality, civil society, and so on. It has integrated or absorbed, within itself, the institutions that exist in objective reality, such that the reality now corresponds to the concept. And on a standard definition of truth, when a concept corresponds to reality, the concept is true. So the unification of Subjective Mind and Objective Mind can be understood as establishing the truth of human society, the creation of a truly human society. Society now really, objectively, corresponds to the subjective concept “human” because it has been transformed so as to become genuinely human.

Here is how Hegel himself put it, in the first 2 paragraphs (paras. 484-5) of the Objective Mind section of the Philosophy of Mind. He says that, although “freedom is [the] inward function and aim” of the free will, the free will stands “in relation to an external and already subsisting objectivity.” “But the purposive action of this will is to realize its concept, Liberty, in these externally objective aspects, making the latter a world moulded by the former … Liberty, shaped into the actuality of a world.”

Is it too much of a stretch to say at this point that “we have entered the new society”?[1]

Theorists’ Reliance on Spontaneity as Evasion of Responsibility

The Johnson-Forest Tendency (JFT) arose within Trotskyism in 1941. The leaders were J. R. Johnson, pen name of CLR James, and Freddie Forest, pen name of Raya Dunayevskaya. Grace Chin Lee, later known as Grace Lee Boggs, became a leader of the JFT as well sometime thereafter. In 1950, the JFT repudiated the concept that social revolution requires a vanguard party to lead the masses, and soon thereafter it left the Trotskyist movement. The JFT became an independent organization, Correspondence Committees.

But once one repudiates the vanguard party concept, what replaces it? This is what Dunayevskaya’s 1953 letters on Hegel’s Absolute Idea and Absolute Mind are about. Near the start of the first letter, that of May 12, she wrote that she is “concerned only with the dialectic of the vanguard party,” the “type of grouping like ours, be it large or small, and its relation to the mass.” Shortly before that, she wrote that, “in the Absolute Idea is the dialectic of the party and … I have just worked it out.”

When James and Lee repudiated the vanguard party concept, what they replaced it with was reliance on the spontaneity of the masses. This did not satisfy Dunayevskaya, partly because she experienced its practical implications and didn’t like them. During its first two years of existence, Correspondence Committees was a private organization; it had no public presence and no public newspaper. But wait; there’s more.

The immediate event that precipitated the 1953 letters was Stalin’s death, as Dunayevskaya recounts in readings for today’s meeting (and elsewhere). She wrote an analysis of what Stalin’s death implied for the USSR, for world affairs, and for the revolutionary movement. Grace Lee refused to publish this analysis “as is” in the organization’s still-private publication. She wanted the organization to emphasize the supposed fact that Stalin’s death was irrelevant to American workers. Her cherry-picked evidence that it didn’t matter to them was the fact that women in one factory—where James’ wife, Selma James, worked––ignored the radio report that Stalin had died and instead exchanged hamburger recipes. Against this, Dunayevskaya stressed what Charles Denby, another worker who was a member of the organization, reported: a co-worker said “I have just the man to replace [Stalin]: my foreman.” A major dispute broke out in the organization and the May 1953 letters followed shortly thereafter.

On page 5 of a 1982 text, “On the Battle of Ideas,” Dunayevskaya refers to “evasion of all responsibility by dumping all responsibility on ‘the masses.’” This clearly seems to be a comment about the 1953 dispute. More broadly it is about the political practice of James and Lee, and the Correspondence Committees, after the JFT left the Trotskyist movement. But I think it is also a comment on James’ and Lee’s theory, on their replacement of the vanguard party concept with reliance on the spontaneity of the masses. If your theory of social transformation relies exclusively on the spontaneous action and thought of the masses, you are dumping all responsibility on them and evading your own responsibility.

Dunayevskaya made this comment about “evasion of all responsibility” in the context of discussing Lee’s response to her May 20, 1953 letter on Absolute Mind. Initially, Lee’s response was very enthusiastic. As Dunayevskaya says in “On the Battle of Ideas,” Lee “had grasped how new, historically new, had been my singling out of the movement from practice to reach the new society.” The May 20 letter does indeed interpret Hegel’s reference to Nature turning to Mind as a movement from practice to the new society. (Hegel wrote, in para. 575 of the Philosophy of Mind, “The Logical principle turns to Nature and Nature to Mind.”) But that’s not all that the May 20 letter does. That much, taken by itself, is consistent with Lee’s reliance on the spontaneity of the masses, and it is consistent with dumping all responsibility on them.

Dialectical Mediation: Mind Itself as “the Mediating Agent”

Against this, Dunayevskaya’s “On the Battle of Ideas” emphasizes the “dialectic[al] mediation” that is articulated in the three syllogisms at the end of the Absolute Mind chapter. And she writes that dialectical mediation “requires a double negation before it can reach a new society.” She emphasizes the word double, and this is the point at which she makes her comment about evasion of responsibility. In other words, she is contrasting dialectical mediation and its double negation to dumping all responsibility on the masses.

I think there are two key points here. One is that there’s a double movement in the three final syllogisms of the Absolute Mind chapter. There’s not only a movement from Nature to Mind, but also a movement from Logic to Nature. Dunayevskaya equates Nature and practice, and she equates Logic and theory. Hence, we have the concept of a dual movement—a movement from theory and a movement from practice. The other key point is the negation involved in this double movement. Both sides, theory and practice, are self-negating. They don’t remain what they were initially. But they don’t disappear, either. They transcend what they were initially.

How do they do so? In the May 20, 1953 letter, Dunayevskaya emphasizes that “Mind itself, the new society, is ‘the mediating agent in the process.’” This is a reference to the second of the three syllogisms, paragraph 576, in which Hegel says that “Mind itself … as the mediating agent in the process … presupposes Nature and couples it with the Logical principle.”

If we continue to “translate” Mind, Nature, and Logic as the new society, practice, and theory, what this means is that the idea of a new society is what joins together the movements from practice and from theory. It is what brings them together in one relation. In the 1982 “On the Battle of Ideas” text, page 5, Dunayevskaya says something similar: “philosophic mediation is the middle that first creates from itself the whole.” And then she comments that Hegel has here not only departed from the systemic structure that his philosophy appeared to have; he has also departed from “spontaneity, or practice, or nature as if these were the whole.” This seems clearly to be another criticism of what Grace Lee—as well as many alleged followers of Dunayevskaya––have taken from the May 20 letter and/or chapter 1 of Philosophy and Revolution.

In what sense are the movements from theory and from practice joined together? They don’t just coexist side by side. They are unified. Yet they don’t become fused into one—as Dunayevskaya continually stressed, there is no synthesis or closure even here, at the end of Hegel’s “system.” His text bears this out. In the final syllogism, paragraph 577, we have what Hegel calls “a unification of the two aspects.” Yet despite this reference to unification, Hegel says, in the very same sentence, that there continue to be “two appearances” of the Idea, Mind and Nature, not one. So the unification isn’t a synthesis of two into one. It seems to consist, instead, of the fact that both sides of the relation, both “nature” and “the action of cognition,” cause the “movement and development.” Put in terms of the movements from practice and from theory, they are co-equal contributors to one and the same process of movement and development.

But the movements from practice and from theory can be co-equal contributors to one and the same process of movement and development only if they are both moving and developing in the same direction. In other words, what makes this possible is that they are both appearances, or manifestations, of one and the same Idea. In both cases, their thought and activity is driving toward making real the idea of a new society that they both share. I think this is at least part of what’s involved in Dunayevskaya’s phrase “philosophic mediation [as] the middle that first creates from itself the whole.” The shared idea of a new society brings the two sides together, and they develop together on its basis.

The “Two Appearances” of the Idea

Prior to the 1953 letters, Dunayevskaya did not have a clear conception of a dual movement, a movement from practice and a movement from theory. She did not have a worked out philosophical framework with which to express the double negation, the transcendence that needs to take place within both sides, in order to reach a new society. Yet a key element of what she was working out, in her reading of the final three syllogism of the Philosophy of Mind, is not something that she acquired then and there, but rather something that she brought to her reading. I’m referring to the point that the idea of a new society is not only driving the thought and activity of revolutionary intellectuals; it is also present among the masses. Empirically, the drive to realize a new society may or may not be the dominant motivation of the vast majority of the population at a given time, but the point here is not to interpret the world, nor to quantify it, but to change it. The point is that there are masses of people struggling for freedom, and what is driving their thought and activity is the idea of a new society.

Dunayevskaya had emphasized this point ever since the 1949-50 general strike of coal miners in Appalachia, where she found that workers weren’t fighting only for higher wages or better working conditions or even employment security. They were asking what kind of labor human beings should do and questioning whether they themselves were free, given that they had to descend into the mines day after day whether they wanted to or not. Dunayevskaya later said that this made concrete, and thereby extended, one of Marx’s most profound concepts, the concept of alienated labor.[2]

There are several indications in the May 12, 1953 letter that Dunayevskaya was reading the chapters on Absolute Idea and Absolute Mind in light of the conception, which she already had, that the idea of a new society is present among both revolutionary intellectuals and masses struggling for freedom. She wrote in that letter that “the self-development of socialism, objectively and subjectively, gives off impulses which come one way to the leader, another way to the class as a whole.” She wrote that, in “our age … the preoccupation of the theorists––freedom out of one-party totalitarianism––is the preoccupation of the great masses.” She wrote that, while “Lenin was aware of the gap between his Universal (‘to a man’) … and the concrete Russian proletariat, … we are more aware of the identity of the Universal and the concrete American proletariat.” She wrote that “objective and subjective are so interpenetrated that the preoccupation of the theoreticians [and] the man on the street is” one and the same preoccupation: “can we be free when what has arisen is the one-party state[?]” (This last remark was not hyperbole. Dunayevskaya was writing before the Hungarian Revolution, the revolt in East Germany, and the revolts in Stalin’s slave-labor camps. At the time, it was not at all clear whether totalitarian rule had permanently crushed all possibility of social transformation.)

So I’m suggesting that, when Dunayevskaya wrote the May 1953 letters, she brought to her reading of Hegel’s texts the view, which she already had, that the idea of a new society is present among both revolutionary intellectuals and masses struggling for freedom. It is not surprising that Dunayevskaya wrote the 1953 letters with this issue in mind. The fight with Grace Lee over her analysis of Stalin’s death, and the whole ensuing dispute throughout the Correspondence Committees, were all about this issue. What Lee emphasized and hailed was the indifference to objective events and to politics of some workers who ignored news of Stalin’s death. What Dunayevskaya emphasized and hailed was the opposite, a worker who said that his foreman was just the person to replace Stalin. This worker was not only interested in objective events and politics. He was treating Stalinism as a class issue that was personally relevant to him, and he was indirectly raising the issue of a new society, by expressing his opposition to the current society, on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

External vs. Dialectical Mediation

I’m a bit concerned that, in my effort to make intelligible the concept of dialectical mediation that Dunayevskaya worked out in the May 20 letter, I may have “succeeded too well.” I don’t mean that literally. I mean that I’m concerned that I may have made it seem somewhat prosaic and mundane.

In order to explain why I don’t think it’s prosaic or mundane, and to understand it better in general, what I want to do is contrast it to the conceptions that Dunayevskaya was breaking from––vanguardism and spontaneism. Vanguardism is the view that social revolution requires the leadership of a vanguard party that brings “revolutionary consciousness” to the masses. Spontaneism is the view that social revolution requires nothing more than the spontaneous activity of the masses.

These two views have long been the dominant views on the revolutionary left. I suspect that lots of people still think of them as the only alternatives.

It is obvious that vanguardism and spontaneism are opposites. But in order to appreciate how they differ from the dialectical mediation that Dunayevskaya was working out in 1953, I want to focus on what vanguardism and spontaneism have in common. And I want to argue that what they have in common is external mediation, as distinct from dialectical mediation, self–mediation. So before I get down to talking about vanguardism and spontaneism, I first want to say a few things about external mediation itself.

All thinking about revolutionary change is about mediation of one kind or another. Revolutionary change is about getting from here to there. And to get from here to there, there has to be something (or someone) in the middle, the mediation (or mediator), that enables us to get from here to there. What distinguishes one view of revolutionary change from another therefore isn’t a matter of mediation vs. non-mediation or immediacy; it’s a matter of what kind of mediation is needed.

In the 1953 letters, and in her subsequent discussions of them, Dunayevskaya frequently refers to the concepts of transition, causality, and essence. I think that what is often, if not always, at issue in these references is external mediation vs. dialectical or self-mediation. Transition, causality, and essence all pertain to external mediation. They don’t pertain to self-mediation, and trying to apply them to self-mediation hinders our ability to understand it.

It’s easy to see that causality involves external mediation. There is something; another thing affects it; and this causes the first thing to change. The thing that causes the first thing to change is an external mediator, and the cause-and-effect process is a process of external mediation.

What about essence? In Hegel’s work, especially in the Science of Logic, essence and its subconcepts are about relations, the relatedness of different things, connections between things, and the dependence of some things on other things. (By “things,” I don’t mean only material objects.) Thus, when Dunayevskaya notes, several times in the May 12, 1953 letter, that Lenin’s reading of the Absolute Idea stresses “objective world connections,” this is a criticism that he didn’t ultimately succeed in moving beyond thinking in terms of essence relations.

In any case, essence relations are external mediations. Some things depend on, are brought about by, are conditioned by, or exist by virtue of other things. They don’t exist on their own; their existence is mediated by something different from them; they are in some sense products of the other things on which they depend (etc.). For example, the capitalist class and the proletariat are forms of appearance, mediated results, of the essential relation that brings them about and on which they depend: a working population deprived of means of production of its own.

What about transition? I think Hegel mainly uses the term transition as a synonym for becoming. A thing, or property of a thing, does not exist, then it does. (Or, it does exist, then it does not.) So there is a process of transition through which it becomes what it was not (or ceases to be what it was). It seems to me that, considering such situations literally, in the way I have just characterized them, transition requires external mediation. Something cannot become what it was not of its own accord. Something external to it must produce, or help to produce, the transition from not-being to being.

What makes this hard to grasp, at least hard for me, is the habit of talking loosely about such things, instead of being strict and literal. For example, an acorn is not an oak tree. We say that it becomes an oak tree. But this isn’t a process of becoming or transition in the above sense, strictly speaking. It’s a case of development and, partly, of self-development. The acorn was never “not an oak tree” in the same way that rocks and humility aren’t oak trees. No amount of sunlight, water, and nutrients will help rocks or humility develop into oak trees. The acorn is different because it was never simply “not an oak tree.” From the start, it was potentially an oak tree. That’s not a transition from not-being to being.

Near the end of her May 12 letter on the Absolute Idea, Dunayevskaya referred to Lenin’s comment that there is a “transition of the logical idea to Nature” in the last paragraph (para. 1817) of Hegel’s Science of Logic. She made a big issue of the fact that Lenin used the word transition and that he dismissed the remainder of the paragraph as “unimportant.” But in the remainder of the paragraph, Hegel clarified that the passage from Logic to Nature is not a transition. Dunayevskaya suggests that this didn’t seem important to Lenin because he “didn’t have Stalinism to overcome.” He was writing at a time when “transitions, revolutions seemed sufficient to bring the new society.” That the revolutionary process might turn into counter-revolution rather than a new society wasn’t part of his thinking. But now, Dunayevskaya wrote, “everyone looks at the totalitarian one-party state[;] that is the new that must be overcome by a totally new revolt in which everyone experiences ‘absolute liberation.’”

The phrase “absolute liberation” is Hegel’s. It was part of his clarification that the passage from Logic to Nature is not a transition. He wrote that Nature is the Idea in the form of being, and that

this determination has not issued from a process of becoming, nor is it a transition …. On the contrary [… it] is an absolute liberation for which there is no longer any immediate determination that is not equally posited and itself Notion; in this freedom, therefore, no transition takes place. … The passage [from Logic to Nature] is therefore to be understood here rather in this manner, that the Idea freely releases itself in its absolute self-assurance and inner poise.[3]

There is a whole lot here. I don’t have time to even begin to discuss most of it. I just want to flag one point: the concepts needed to grasp dialectical mediation and to think in terms of it (such as self-development and free release) are different from the concepts needed to grasp and think in terms of external mediation (such as causality and transition).

In the Prologue to “25 Years of Marxist-Humanism in the U.S.” (p. 3), Dunayevskaya quotes from a July 1949 letter, that Grace Lee wrote to her and CLR James, about this issue. Dunayevskaya prefaces the quotation by saying that, in this letter, “Lee began seriously to go at Lenin’s Notebooks [on Hegel’s Science of Logic] as well as Hegel’s Doctrine of the Notion [or Concept, in the Science of Logic]. Lee wrote, “In the final section on Essence (Causality) and the beginning of the section on Notion, Lenin breaks with this kind (Kantian) of inconsistent empiricism. He sees the limitation of the scientific method., e.g., the category of causality[,] to explain the relation between mind and matter. Freedom, subjectivity, notion––these are the categories by which we will gain knowledge of the objectively real.”

The point isn’t that scientific method is worthless or even flawed. It isn’t that concepts such as transition, causality, and essence are worthless or even flawed. The point is that they have what Lee called a “limitation”; they have a limited range of applicability. It’s not the case that everything can be discussed in terms of them.

I suggested above that Dunayevskaya’s references to causality, essence, and transition, in the 1953 letters and elsewhere, are often about the issue of external mediation vs. dialectical or self-mediation. I think that some of her references to logic are also about the same issue. The references I’m thinking of are ones in which the term logic refers to relations that are like links of a chain, wherein each link follows necessarily from, and requires, the previous links. A syllogism––for example, Socrates is a man; all men are mortal; therefore, Socrates is mortal––is a classic example of this sense of logic. I think Dunayevskaya uses the term logic in this way when she discusses “the logic of Capital” near the end of the May 12 letter, and when she writes in Philosophy and Revolution (p. 41) that “Logic is altogether replaced by the self-thinking Idea” in the final syllogism of the Philosophy of Mind. She’s certainly not saying that we’ll all be illogical in the new society! Part of her point is that, in contrast to the previous syllogisms, the term Logic doesn’t appear in this one. But I think she’s also suggesting that the final syllogism really isn’t a syllogism at all. It doesn’t have the structure of one thing necessarily leading to another that then necessarily leads to a third.

Both Vanguardism and Spontaneism Rely on External Mediation

It is easy to see that the vanguardist conception of revolutionary change relies on external mediation. On the vanguardist perspective, successful social revolution requires “revolutionary consciousness.” But the masses do not have revolutionary consciousness and they cannot acquire it on their own. It needs to be brought to them, from outside, by the revolutionary intellectuals. The “bringing from outside” is external mediation and the revolutionary intellectuals are thus external mediators.

What about spontaneism? It seems different. Its conception of revolutionary change seems to rely on the spontaneous activity of the masses. And that’s not wrong. It’s just incomplete. Considered abstractly, spontaneous activity could lead to anything, or to nothing at all. So what is brought into the mix is some assurance that spontaneous activity will lead to forward development.

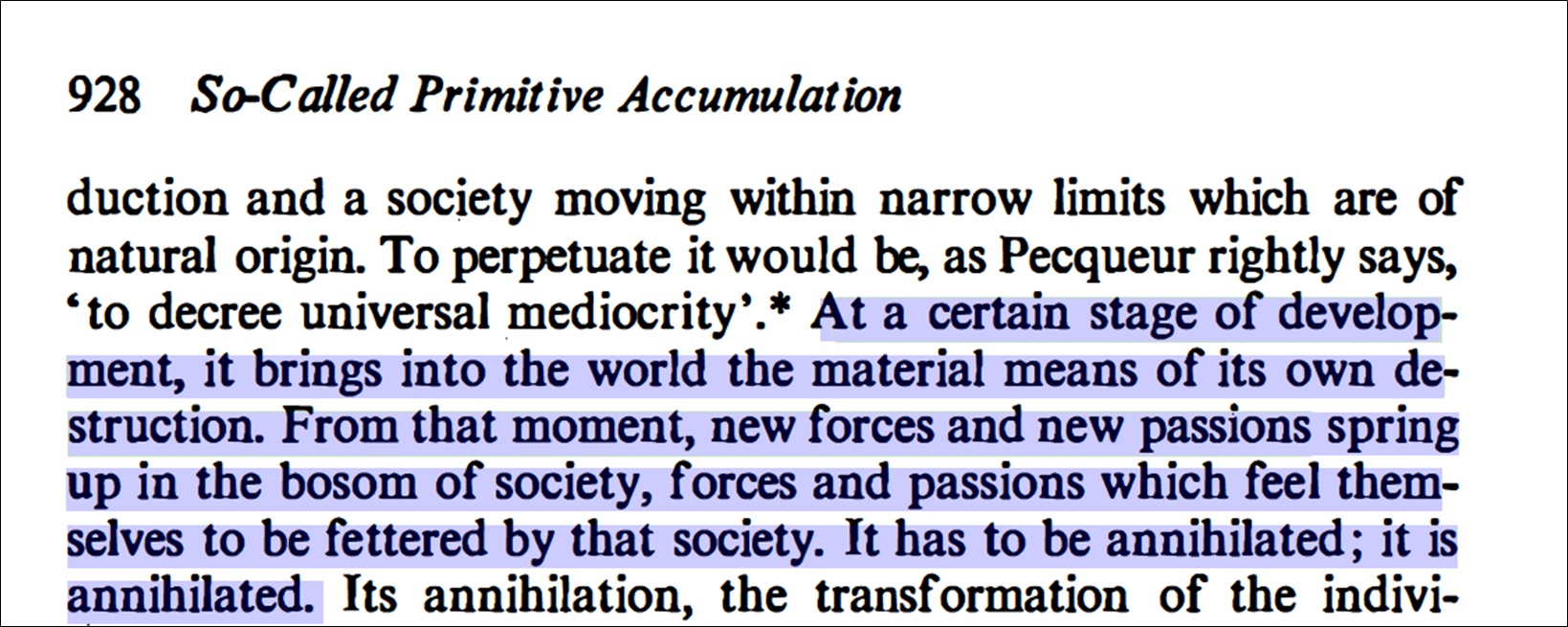

This is particularly true in the case of CLR James. In Dunayevskaya’s 1953 letters, there is one brief reference to the assurance he offered, near the end of the May 12 letter. It’s easy to miss, but I think it’s hugely significant, because the response to it that Dunayevskaya begins to develop there is hugely significant. Right after discussing Lenin vs. Hegel on transition versus absolute liberation, she begins to discuss the penultimate chapter of volume 1 of Marx’s Capital, “The Historical Tendency of Capitalist Accumulation.” (She refers to this as the last chapter, which it isn’t, though it is indeed the book’s culmination.) She notes that Marx is projecting the ultimate development of capitalism, one aspect of which is the centralization of capital in fewer hands. The other is the revolt of the workers that is “organized, united, disciplined by the very mechanism of capitalist production.”

The words she quotes at the end––“organized, united, disciplined by the very mechanism of capitalist production”––are Marx’s, but they were repeated ad nauseum by James, both before and after these letters. He even managed somehow to smuggle them into a November, 1963 talk in the midst of discussing the assassination of John F. Kennedy (Marxism for Our Times, p. 63). Go figure.

In any case, this was the assurance that James offered. Revolutionary change requires nothing more than the spontaneous activity of the working class because the very mechanism of capitalist production itself is organizing and uniting it, and giving it discipline, and (as Marx also said at this point) the revolt of the workers proceeds apace with the accumulation and centralization of capital and the worsening lot of the workers that they create. So not only is there no need for vanguard party leadership. There is also no need for theory or philosophy.

In this conception, there is no group of people who act as external mediators of the revolutionary process. In that respect, it differs from the vanguardist conception, in which the external mediators are revolutionary intellectuals. Yet in James’ conception, there is external mediation nonetheless. Objective conditions, especially “the very mechanism of capitalist production,” are the external mediators.

In this case, too, there are a lot of things that deserve discussion, and I can’t even begin to do it justice here. I just want to mention a few things about Dunayevskaya’s response. I think she provided the most important part of her response in advance, when, discussing Lenin, she said that focusing on transition, revolution, provides no assurance against counter-revolution. So she didn’t disagree with James about the spontaneous drive of the working class toward revolution, or the part about it being “organized, united, disciplined by the very mechanism of capitalist production.” She instead argued that this is insufficient. To ensure the success of the revolutionary process, not just the overthrown of the existing society but the creation of a new society, dialectical mediation––in which everyone experiences “absolute liberation”––is needed.

Also in the May 12 letter, she began to work out the view that Marx’s discussion in the penultimate chapter of Capital developed the contradictions of capitalism to their ultimate point but did not resolve them. She wrote that “the logic of Capital is … the state capitalism at one pole [state-capitalism being the limiting point of the centralization of capital] and the revolt at the other.” He then said that the expropriators are expropriated and that this is a negation of the negation. But, Dunayevskaya continued, “Marx did not make the negation of the negation any more concrete.” Her point seems to be that Marx, in the penultimate chapter of Capital, was not pretending to provide a complete or sufficient account of the process of social revolution.

This idea was elaborated more fully later, especially in pages 92–94 of Philosophy and Revolution, where, among other things, Dunayevskaya clarifies her comment in the May 12 letter that Marx’s “general Absolute Law [of capitalist accumulation] … is based on The Absolute Idea” (emphasis omitted).

Finally, let me note another thing that responds to James that wasn’t in the 1953 letters, but which became crucially important to Dunayevskaya later—the concept of “New Passions and New Forces,” which is the title of the final chapter of Philosophy and Revolution. The source of the phrase is the same penultimate chapter of Capital. Marx was at that point discussing the emergence of capitalism. He wrote that, at a certain point, “new forces and new passions spring up in the bosom of society, forces and passions which feel themselves to be fettered by that society. It has to be annihilated; it is annihilated.” Now, the new forces and new passions he’s referring to are the nascent bourgeoisie and its greed and so forth, which is a world apart from the passion for universal freedom and a universal class, the proletariat, that can bring it into being. But I think that, by flagging this phrase, Dunayevskaya was, among other things, signaling that Marx understood that a revolutionary process requires more than the external mediation that objective conditions provides. It requires a subjective element––“forces and passions which feel themselves to be fettered” (my emphasis) by the existing society.

For further discussion of this issue, please see my article of July 2, 2009, in With Sober Senses, entitled “On ‘New Passions and New Forces.’”

Notes

[1] The concluding words of Dunayevskaya’s May 20, 1953 letter are “We have entered the new society.”

[2] See her November 1955 letter that precedes the texts of the May 1953 letters.

[3] A more recent translation renders the start of this passage as “This determination, however, is nothing that has become, is not a transition ….”

Andrew writes in the introduction to his article that:

“Near the start of the first letter, that of May 12, she wrote that she is ‘concerned only with the dialectic of the vanguard party,’ the ‘type of grouping like ours, be it large or small, and its relation to the mass.”’ Shortly before that, she wrote that, ‘in the Absolute Idea is the dialectic of the party and … I have just worked it out.'”

I read these letters before trying to seriously grapple with Hegel but they still resonated with me on an intuitive level. Now that I have begun to read Hegel seriously I wanted to share a related insight to Andrew’s talk. The insight is that the dialectic of the Party can be seen in Hegel as early as the Doctrine of Being.

In the chapter Existence under section b. Quality on page 86, paragraph 2 Hegel writes: “absolute unity that will later emerge is not to be understood as a tempering, a mutual restriction, or blending.” In one of the rare cases where Hegel gives a somewhat intelligible example he says just above that “power should be tempered with wisdom — but is then no longer power as such, for it is subject to wisdom. Wisdom should be expanded into power, but then it vanishes as end and measure setting wisdom.” For Hegel then, Absolute Unity is not achieved by a blending of power and wisdom, the tempering of a quality and its Other.

Power is an expression of quality, which is existence/reality, and wisdom is Other and vice versa. Here Hegel is just using examples, I think we are safe to use other examples. I would like to use practice and theory, which I think fit because practice is in fact a concrete expression of quality in the abstract — existence/reality; theory is its Other. But of course theory is also an expression of existence and reality — thoughts exist as ideas, eventually as forces in the world. The basic way post-Marxist Marxists conceive of this relationship is to see practice as objective and theory as subjective.

What immediately follows is the need to unite practice and theory. They then go about this by developing organizations that bring mass practice and socialist theory together. They subject mass practice to socialist theory and subject socialist theory to mass practice; ‘truth is tested in practice’ as the saying goes. They call their theory-informed-practice and practically-tested-theory praxis. What I think Dunayevslaya and Andrew were getting at and surely what I am getting it as that this external mediation effectively cuts off the possibility of reaching praxis, Absolute Unity between theory and practice because it just an act of blending, of tempering, or mutual restriction.

What we have to do instead is follow practice and theory on their own independent journeys in the dialectic. We have to watch practice turn in a subjective expression of quality. This process is what Dunayevskaya calls the movement from practice that is itself a form of theory. For example, in BC telephone operators in the 1980s were threatened with a lock out. They decided instead to lock out their bosses, managers, and the cops and continue to run the workplace themselves. This practice is more than just blind activity, it became a theory: workers control of production.

Similarly we have to follow along as theory becomes an objective expression of quality. This is the movement from theory towards philosophy. But how is philosophy objective? Hegel conceives of philosophy as the comprehension of our times. Our times is infinity in that it is everything that currently exists and everything that is not yet. Our times is absolutely everything. Philosophy then is the comprehension of everything. But if something was to comprehend everything that it would also have to comprehend itself as part of that reality, that is, it would acknowledge have to take itself as an object of comprehension. Systematic philosophy by its very nature objectifies itself its quest for objective truth.

What is at stake in social revolution is distinguishing between these movements and being concerned about what the conditions of their reunification are. If the reunification is not a blending between practice and theory then it must be a sublation; praxis is not mere theoretically informed practice and practice tested theory. Praxis is the combined movement of practice to theory and theory to philosophy. In Praxis there is a dual movement distinguished and unified.

I think it is clear as this point that in order for practice to develop into theory it needs to attempt to comprehend itself and the reality in which it takes place. I also think it is clear that to be able to do this it will need a philosophy that worked out that reality. The “completion” of the movement from practice presupposes the completion of the movement from theory. But this could be said the other way around: to in order for theory to become philosophy it needs to comprehend the movement of practice. Therefore the completion of the movement from theory presupposes the completion of the movement from practice.

I think the mistake to be made here, although I am yet able to “prove” this yet because I don’t yet understand what Hegel determines as the mediation of becoming itself, is to chain down Praxis into a single determinate form. My hunch is Praxis is becoming itself and to reduce it to a determinate form would be to negate it, annihilate it in a particular moment. To me this doesn’t mean no organization, a blind faith in the masses, it means a multiplicity of ephemeral forms; a constellation of organizations that are self-consciously temporary yet no less committed to their specific purpose. Becoming can not be exhausted by determinate forms and therefore Praxis can not be embodied in any organizational form. It can only be embodied in the interaction between organizations trying to freely develop theory into philosophy and organizations trying to freely develop practice into theory.

The organizational point I think I have arrived on is that organizations must necessarily see themselves as discreet, as part of a totality. Once we start to see ourselves as the totality we have already substituted ourselves for movement, that is Praxis, itself. We have destroyed the road towards Absolute Unity of practice and theory.