by Gabriel Donnelly [1]

Lessons from the Past: Dunayevskaya’s Writings on Reaganism in Dialogue with Today’s Struggle Against Trumpism

Marxist-Humanist Initiative recently held a public meeting on Raya Dunayevskaya’s writings on the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan. Our goal was to use Dunayevskaya’s consideration of Reagan to help deepen our understanding of and struggle against Trumpism.

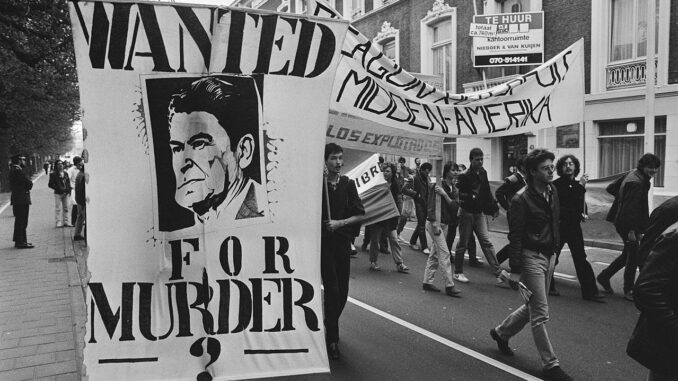

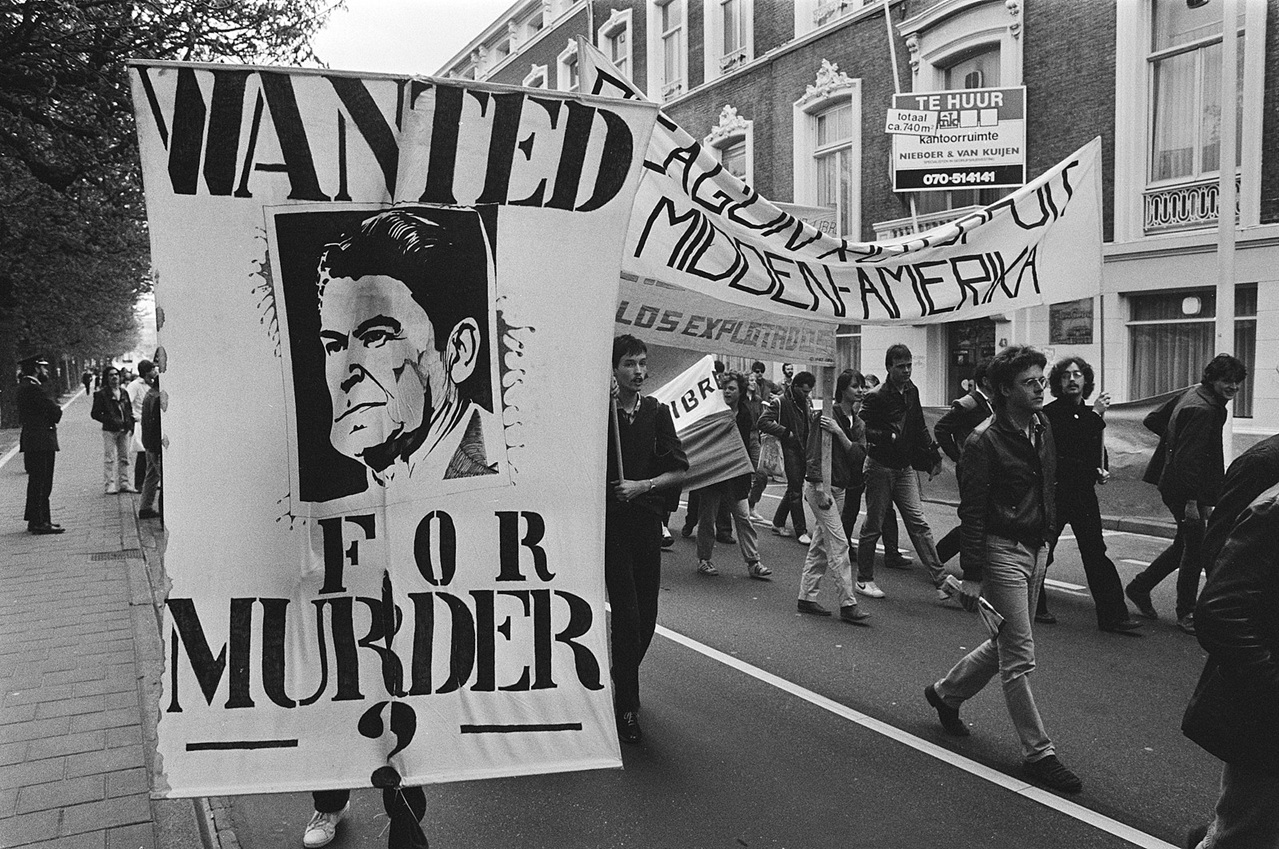

Dunayevskaya recognized that Reagan was emblematic of a new stage of reaction. He was not merely a continuation of Eisenhower-Nixon-Ford Republican conservatism. Reaganism was a retrogressive and actively reactionary politics that sought to undo all the progressive gains in America that had been won during the twenty years prior to Reagan’s election. In particular, it was a direct assault on the gains of the Civil Rights Movement and the labor movement. And ultimately, Reagan wanted to dismantle the welfare-state measures that were first instituted in the New Deal of the 1930s.

In the October 1986 issue of News & Letters, Dunayevskaya had this to say about the all-encompassing effect of the new stage of Reagan’s retrogression:

it’s a much more dangerous world today—a changed world. Reagan’s retrogressionism has so deadened bourgeois thought itself that there is no whisper of dissent either from academia or the media, much less Congress; technology has become a living monster that forces us to face the threat to the very survival of civilization.

These words speak to this moment as much as they spoke to their own. Dunayevskaya’s description of a stifled time, where no institution dissents from the barbarism of reaction, feels much like life under Trumpism. She was referring to the threat of nuclear war. We again live under the shadow of nuclear armageddon but, in addition, under the shadow of climate catastrophe.

In the same issue, Dunayevskaya wrote, “What is a still greater delusion today is Reagan’s idea that his Pax American can be imposed upon the masses—counter-revolution on a world scale” (p. 10). We see here the roots of Make America Great Again’s imperialist ambitions. In the MAGA mindset, the Canadian and Mexican proletariat must be punished, or annexed, to strengthen the American economy.But the MAGA mindset favors this, not just to further the nationalist imperatives of America First, but out of a genuine desire to punish these countries for their perceived weakness or liberalism.

Still, it is not enough to just draw comparisons as we look backward, since we can’t afford to let the theoretical work that Dunayevskaya put into understanding Reaganism go to waste. The conclusions of that theoretical work can be extrapolated from and built on for our time. We must continue to “concretize” Marxist-Humanist philosophy, i.e., to use Marx’s Marxism and its further elaboration by Raya Dunayevskaya—including her novel interpretation of the Hegelian dialectic—to analyze the political situation today, past periods of retrogression, and responses to that retrogression.

Dunayevskaya’s understanding of Reagan as the spearhead of a retrogression has to be considered in connection with her understanding of the Eastern European revolts of the 1950s. In the June 1985 issue of News & Letters, Dunayevskaya wrote at length about those revolts in relation to Reagan as a counterrevolutionary:

The void in Reagan’s mind of any serious sense of history would hardly make him conscious of the fact that the post-World War II world has given birth to a totally new movement from practice that is itself a form of theory. [p. 10]

The “totally new movement from practice,” that Dunayevskaya is referring to here is the humanism of the working-class and other freedom struggles, East, West, and South, that emerged after World War II. Marxist-Humanism, the philosophical articulation of the same humanist idea, emerged during the same period. It was Marxist-Humanism that provided a challenge to both the authoritarianism of Stalin and the retrogressionism of Reagan.

One quibble that the soft-on-Trump left is fond of raising is that Trump can’t be a counterrevolutionary fascist, because there’s been no revolutionary unrest for him to quell. This is an instance of the kind of programmatic and schematic thinking that plagues the soft-on-Trump left. For a political movement to be called fascist, in this manner of thinking, it has to match all the items on a checklist. Historically, the European fascist movements were born out of moments of great unrest when revolution seemed very possible in those countries. Franco conquered Spain by defeating the Spanish Revolution, etc. etc.

However, there doesn’t need to be a thriving Communist-Party-led mass movement for fascists to come to power. Reagan was not responding to revolutionary unrest, but to the gains won over thirty years of Civil Rights struggle and to New Deal reforms. Trumpism is confronting a similar moment. There is no revolutionary stirring in contemporary America, but the George Floyd Uprising in Trump’s first term signaled the appearance of an anti-racist majority in the US, with substantial support globally. This is what infuriates the Trumpists, and it is why Ben Shapiro is campaigning to get Trump to pardon Derek Chauvin. The far right is fighting demographic changes, and it is furious at attacks on White Nationalism. It wants total retrogression—complete rollback of the ideas of political accountability for police violence and dignity for Black Americans. That is Trump’s retrogression; it is what he embodies and enables.

In the June 1985 issue of News & Letters, Dunayevskaya referred to the Spanish Revolution and Franco’s defeat of it, when she wrote at length about Reagan having visited Nazi graves in Bitburg, Germany. There were mass protests in Spain condemning that visit. Dunayevskaya commented:

remembrance of what the Spanish Revolution represented … was the real reason for the massiveness of this outpouring. Nor was it only a question of the past and the U.S. allowing Franco to win. It was Reagan’s most recent rewriting of history when he dared to utter: “Most Americans were on Franco’s side in the Spanish Civil War.” The reaction of the Spanish masses was to burn the American flag.

The alternatives to Reaganism that Dunayevskaya identified were the exact historical tendencies that Reagan sought to pave over. In the historical imaginary of Reaganism, there had never been a concerted, humanist resistance to Franco. Dunayevskaya shows—not just in her theoretical work but in the concrete example of the furious Spanish masses—how the excavation, understanding, and preservation of that struggle is part of the path forward.

In our moment, we can see that a similar struggle, fought along similar lines, is needed. We can’t allow the “new movement from practice” that emerged in the aftermath of the barbarity of World War II to be smothered. We can’t allow the gains and history of the Civil Rights Movement to be steamrolled over. Since Trump keeps comparing himself to McKinley, it is our responsibility to remind him that the struggle has evolved considerably, both theoretically and practically, in the 124 years since McKinley’s administration.

* * *

Readers are encouraged to explore the following short pieces by Dunayevskaya on the Reagan retrogression, which include those discussed above:

October 1980, page 1

July 1983, page 1

June 1985, page 1 (bottom)

October 1986, page 1

NOTE

[1] The author thanks Ralph Keller.

Be the first to comment