Henryk Grossman’s Law of the Relative Fall in the Mass of Profit as “Correction” of Marx’s Law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit

by Michael Rednitz

1. Introduction

Henryk Grossman transforms Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall into his own law of the relative fall in the mass of profit. In this article, I offer an in-depth analysis of Grossman’s transformation of Marx’s law by means of his “corrections” of Marx’s original text.[1]

Andrew Kliman has demonstrated mathematically that Grossman’s breakdown theory is fundamentally flawed.[2] Here, I engage in a close reading of a small portion of Grossman’s book that will uncover his attempts to make his view seem to be the view of Marx.

I will focus on just three pages—pages 193-195 in Grossman (1929 E2), The Law of Accumulation and the Breakdown of the Capitalist System, Being also a Theory of Crises. The three pages under investigation form the latter part of section 11 of the book’s second chapter, “Causes of the Misunderstanding of Marx’s Theory of Accumulation and Breakdown.”

By dealing with such a small sample, just three pages, I cannot claim that my investigation is representative of The Law of Accumulation and the Breakdown of the Capitalist System as a whole. All I want to do is to investigate the validity of Grossman’s references to Marx’s writings on pages 193-195. However, these three pages are especially important for Grossman’s transformation of Marx’s law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit into a law of a falling relative mass of profit. If the arguments and references contained in these pages turn out to be invalid, Grossman’s breakdown theory as a whole will be affected.

In matters of exegetics, reading Grossman is a challenge. Sometimes his citations from Marx’s writings are not free from copying errors; often his references are not pertinent to the point under discussion; and very often, if not always, he fails to indicate that he has added or changed emphases in quotations.

Rick Kuhn, Grossman’s conscientious editor, is well aware of this problem, given his in-depth knowledge of Grossman’s oeuvre. In some cases, therefore, he offers an editor’s comment when Grossman commits one of his referencing errors. However, Kuhn’s list of Grossman’s sometimes venial, sometimes mortal, referencing sins is decidedly too short. A charitable reading of Grossman’s writing must understand him against his references. To put it pointedly: a charitable reader can only understand him despite his references, not because of them. The reader must decide on the reference’s correctness and pertinence on a case-by-case basis. In my opinion, in the pages under discussion, all of Grossman’s Marx-references are invalid.

This, of course, is a strong claim, and different readers may come to different results. This is especially to be expected from Grossman experts. I will therefore document the larger context of Grossman’s Marx-references, I will present my own interpretation of the enlarged referenced text, and I will explain why I think that Grossman’s reference is invalid. Readers of this article, especially adherents of the Grossman school, are invited to question my conclusions.

In some cases, it is difficult to reconcile Grossman’s main text with his numerical reproduction schemes. To address this point, I recalculate his schemes and, based on this recalculation, I present graphs and tables that help to clarify Grossman’s arguments and to characterize incompatibilities between Grossman’s main text and his scheme.

2. Grossman’s Breakdown Theory and its Value-Theoretic Refutation: Some Brief Remarks

In several writings, Andrew Kliman has demonstrated that Grossman’s theory of breakdown is fundamentally flawed (Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021a; Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021b, Kliman, Jan. 25, 2022; Kliman, Jan. 26, 2022; Kliman, Jan. 27, 2022; Kliman, May 27, 2022; Kliman, Sept. 13, 2023; Kliman, Oct. 11, 2024).

I understand this refutation to be a well-established result, since nobody has thus far come up with a refutation of his refutation. My article will not add anything of theoretical importance to Kliman’s analysis. Rather, its main purpose is to investigate the interpretative strategy that Grossman employs to transform Marx’s rate-of-profit theory into a mass-of-profit theory. With this transformation, Grossman’s intends to make his own theory appear to be the theory of Marx.

Before I begin my investigation of Grossman’s interpretative strategy, I offer some basic information about Grossman’s breakdown theory and its value-theoretic refutation. To do so, I start with a footnote by Kliman (Oct. 7, 2021a, footnote 3).

[Fn 3.] The mass of profit does not actually fall in the Bauer-Grossmann scheme prior to the moment of breakdown. By assumption, it increases by 5% per annum. What begins to fall, starting in year 21, and what disappears at the moment of breakdown, is capitalists’ revenue—the portion of profit that capitalists keep as personal income instead of accumulating it as additional capital. Grossmann’s formulations sometimes gloss over the distinction; but this terminological problem has no direct bearing on the issue of breakdown. Breakdown allegedly occurs when the total mass of profit—the portion accumulated as additional capital plus the portion kept as revenue—is too small to allow capital accumulation to continue at the going rate. This is necessarily the moment when, if capitalists do attempt to accumulate at the going rate, there is no profit left for them to keep as revenue.

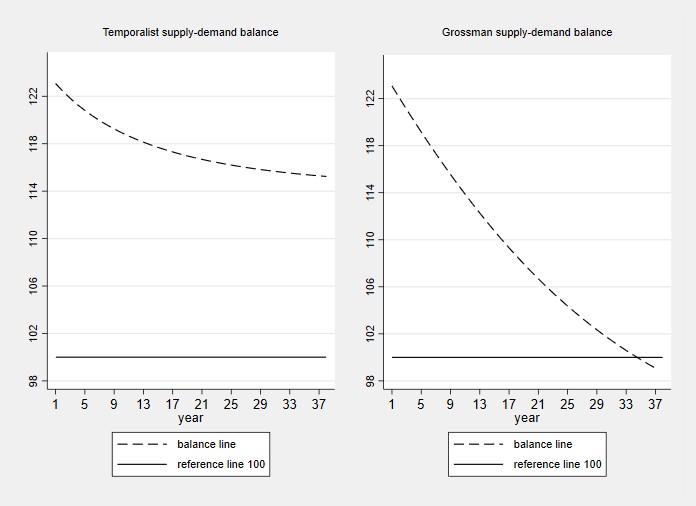

This footnote addresses, in a nutshell, important aspects of the subject matter that we should keep in mind as background information. Figures 1a and 1b, below, illustrate some of the points it addresses.

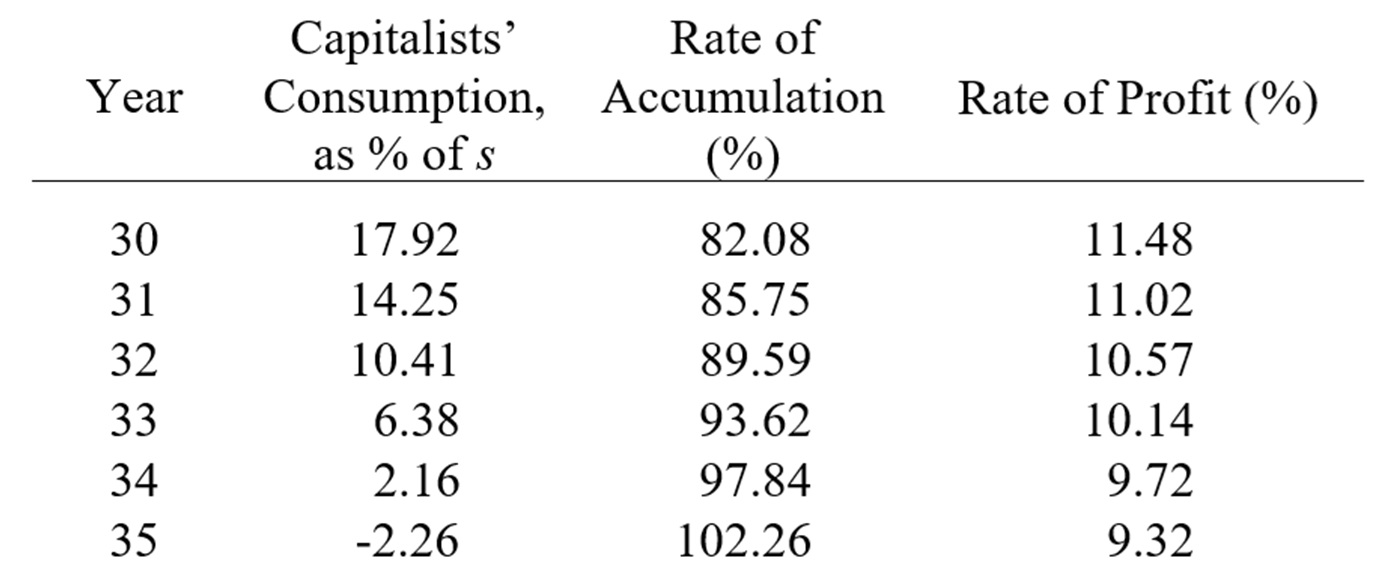

Figure 1a. Indicators Explicitly or Implicitly Used by Grossman

In Figure 1a, both panels are based on my recalculation of the Grossman-Bauer scheme (Grossman 1929 E2: 136), using the algorithm in Andrew Kliman’s spreadsheet file (Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021b). Provided with this dataset, we can depict the evolution of the mass of profit (or surplus-value) and of capitalists’ consumption.

As we see in the left panel, the mass of profit is rising throughout the time span under observation. It is totally driven, as mentioned above, by Grossman’s assumptions. By contrast, capitalists’ consumption stops rising after Year 20 and then starts its ever-faster decline. Since the rate of accumulation is given, and since the mass of profit is given as well, capitalists’ consumption, or the portion of profit that is kept as revenue, amounts to the difference between the given mass of profit and the prescribed amount of profit invested. In other words, capitalists must do with what is left over; the revenue they use for personal consumption is whatever remains after a pregiven portion of a pregiven amount of profit has been allocated for accumulation. Thus, the movement of capitalists’ consumption is likewise driven by the scheme’s assumptions.

In Year 35, revenue (or capitalists’ consumption), represented by the perforated line, hits the reference line (amount = zero). Under the scheme’s assumptions, there is nothing left for capitalists’ consumption, and the accumulation process breaks down.

The panel on the right side of Figure 1a compares the “relative mass of surplus-value,” Grossman’s favored ratio, to the disfavored rate of profit. Of course, the rate of profit itself measures the relative mass of surplus-value, since it is the mass of surplus-value in relation to the total capital advanced. Understood in this manner, “relative mass of surplus-value (profit)” and “rate of profit” are nothing more than different names for the same statistical concept. However, what Grossman meant by the “relative mass of surplus-value” is the mass of surplus-value in relation to the constant capital advanced, rather than in relation to the total capital advanced.

Despite the difference, the trajectory of this latter “relative mass of surplus-value” continues to closely reflect the trajectory of the rate of profit, as the right panel of Figure 1a illustrates. Grossman’s relative mass of surplus-value is the long-dashed line; the rate of profit is the solid line. The key difference is that the former starts at 50% while the latter starts at 33%. Because Grossman’s favored measure starts higher, it drops faster and thus gives a more accentuated picture of the indicator’s decline.

Yet neither Grossman’s “relative amount of surplus-value” nor the conventional rate of profit are well-suited to depict a breakdown of the accumulation process. Such a breakdown becomes visible, however, where the short-dashed line representing “the relative mass of k” (k = capitalists’ consumption) hits the reference line (ratio = zero).

Thus, after all the terminological contortions about the relative mass of profit (surplus-value), it is most probably the relative mass of revenue that Grossman has in mind when he looks for the scheme’s breakdown point. That is, he is looking for the point at which “there is no profit left for [the capitalists] to keep as revenue” (Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021a, footnote 3, cited above). We can look for the breakdown point by considering a second perspective (see Figure 1b, below).

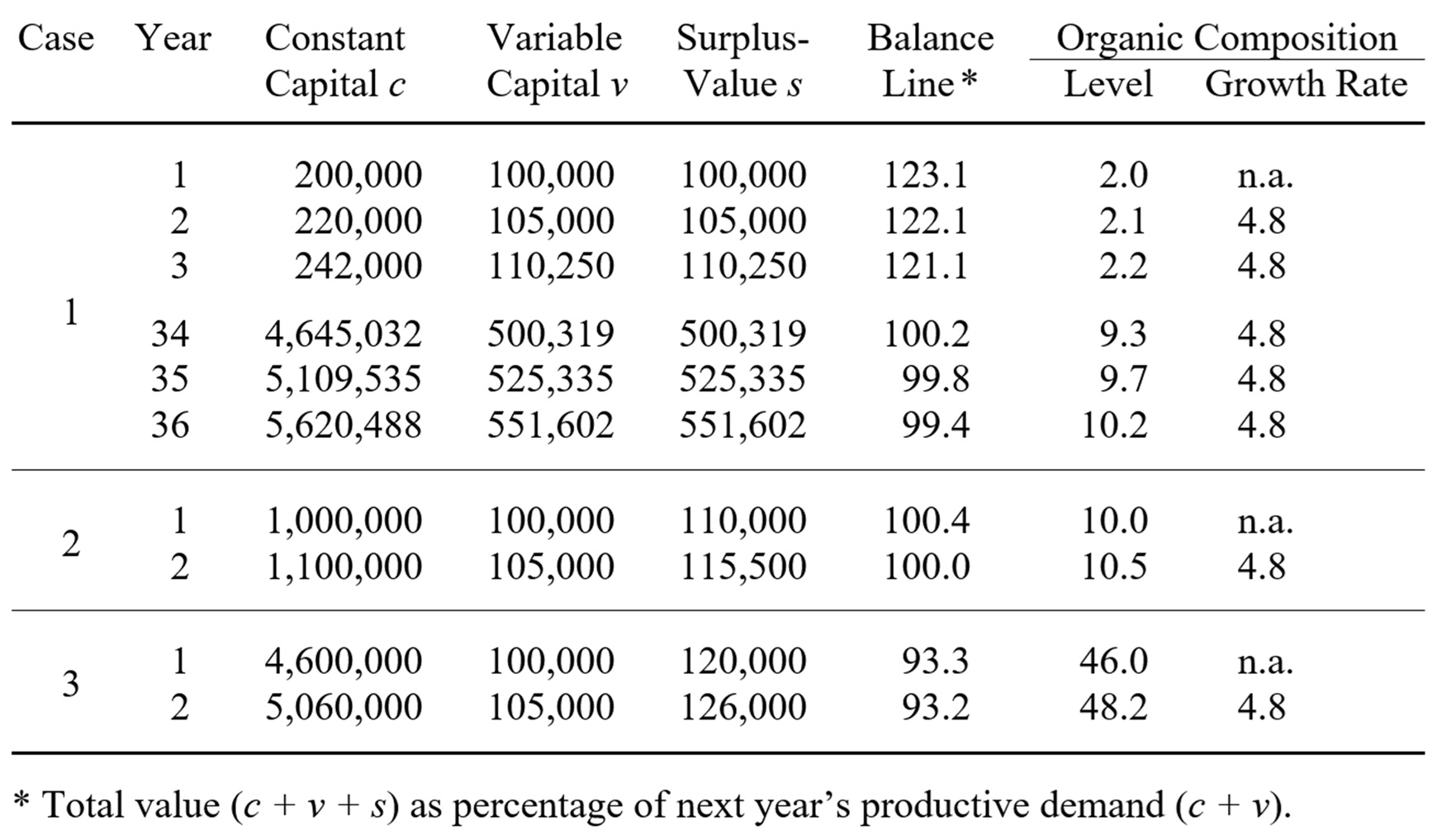

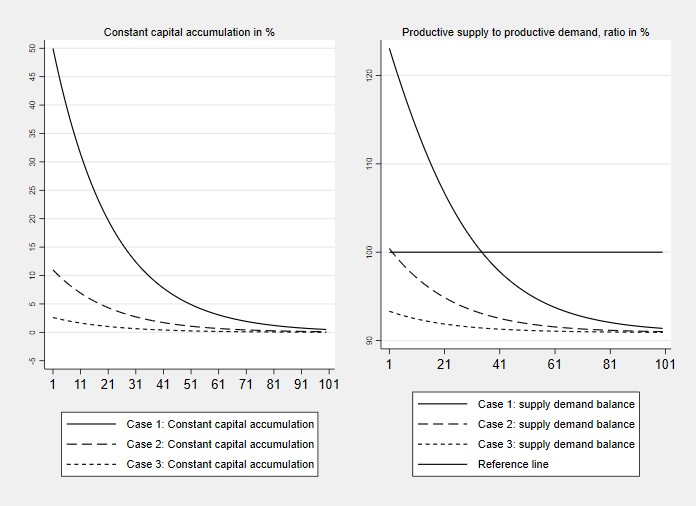

Figure 1b. Supply-Demand Balance Lines: Kliman’s Spreadsheet and Grossman’s Scheme Compared

Figure 1b compares a default supply-demand balance in Andrew Kliman’s interactive spreadsheet file (Oct. 7, 2021b) to the supply-demand balance implicit in Grossman’s (1929 E2: 136) Table 2. By “supply-demand balance,” I mean the total value in the present year (wt = ct + vt + st) as a percent of the following year’s productive demand (ct+1 + vt+1 ). As far as I know, Grossman himself nowhere proposed the concept of a supply-demand balance, but it can easily be calculated from his scheme, given his initial values for the variables and their stipulated growth rates (c grows by 10% per annum; v and s grow by 5% per annum).

Both balance lines, i.e., the long-dashed lines in the left and right panels, start at the value of 123%. This is true because the initial values for c, v, and s follow the same comparative relations (c = 2, v = 1, s = 1 in Kliman’s default version; c = 200,000, v = 100,000, s = 100,000 in Grossman’s scheme), and because the initial growth rates of c and v are the same in both cases (though the growth rate of c, which remains constant in Grossman’s scheme, later declines in Kliman’s scenario).

While Grossman’s reproduction scheme assumes that per-unit prices remain constant over time, Kliman’s interactive spreadsheet illustrates the relationship between rising labor productivity and falling per-unit prices (values), determined according to Marx’s theory. The growing organic composition of capital, insofar as it is accompanied by increasing labor productivity, lowers the per-unit prices of productive output. Consequently, when per-unit prices are determined endogenously, as required by Marx’s theory, any breakdown tendency is dissolved (Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021a).

The balance line in the left-side panel refers to the spreadsheet’s default version.[3] Beyond the default version, Kliman’s interactive tool allows different values to be assumed for each of the key variables. Different assumptions will produce balance lines that differ in their levels and rates of annual decline, but they will share one common property: they will approach a horizontal line above the reference line—or, put differently, they will never reach a breakdown point.

In contrast, Grossman’s balance line is fully assumption-driven: it fails to account for declining per-unit output prices due to rising labor productivity. Like capitalists’ consumption, it cuts across the reference line in year 35. Thus, the depiction of Grossman’s balance line spells out a basic result of Kliman’s refutation: in Grossman’s world of reproduction schemes, assumption-driven accumulation breaks down as soon as the supply of output is too small to satisfy the following year’s productive demand for means of production and subsistence.[4]

This short summary of Grossman’s breakdown theory and its refutation by Andrew Kliman will suffice as a background for my investigation of Grossman’s interpretative strategy.

3. Grossman’s “Correction” of Marx’s Text on the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit

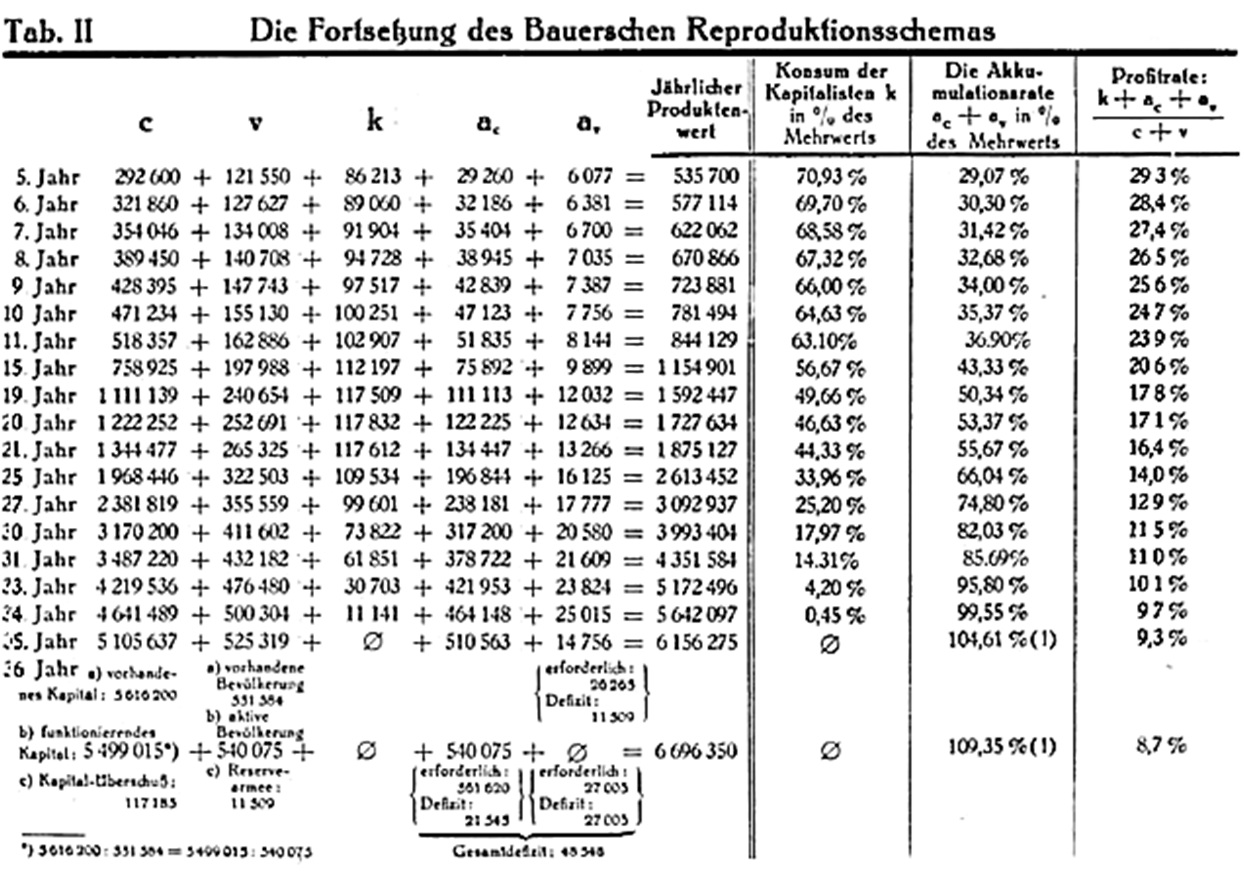

In Grossman’s opus magnum, Table 2 is at centre stage (1929 E2: 136). He begins with Otto Bauer’s scheme of accumulation (1929 E2: 123), summarizes it as a one-good scheme by aggregating the economy’s two departments, extends the period of observation from Bauer’s four years to a time span of 35 years, and applies the same assumptions as Bauer. The result is Grossman’s Table 2, which is his tabular demonstration of capitalism’s (or the scheme’s) breakdown. The assumptions underlying Table 2, aside from the initial values for constant capital and for variable capital, are as follows: constant capital, c, grows annually by 10%; variable capital, v, grows by 5%, the rate of exploitation is 1 (100%) in Year 1 and remains constant throughout the 35 years under investigation. Thus, since s, the surplus-value, equals v if the rate of exploitation is 1, the mass of surplus-value grows by 5% per annum. With these assumptions, the annual rate of accumulation is pregiven as well.

Grossman insists that Marx actually wanted to deal with the relative fall of the mass of profit, rather than with the fall in the rate of profit. With highest likelihood, Grossman says, it was an editing mistake of Engels—who had consulted Samuel Moore, a renowned Cambridge mathematician—that seriously distorted the true meaning of Marx’s argument. Possibly it was even Marx himself who inadvertently committed a writing mistake. In Grossman’s view, it was Engels’s or even Marx’s erroneous replacement of just one single word, “mass,” by “rate,” that led many writers astray in their search for the true causes of capitalism’s final breakdown:

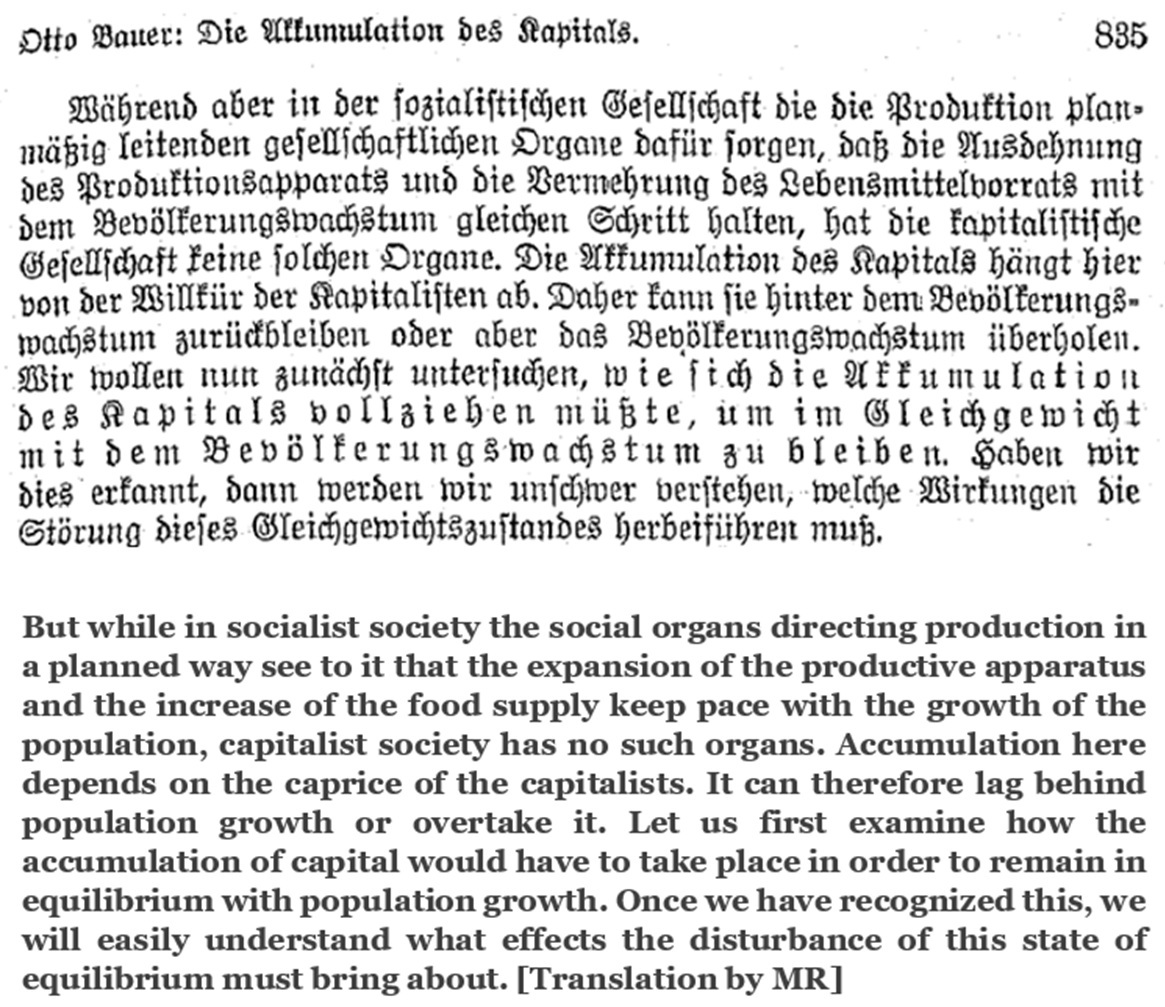

Apparently, the circumstance that the third chapter of the first part of the third volume of Capital—where the relationship between the rate of profit and the rate of surplus value is discussed and serves as the basis for the derivation of the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit—existed as a “series of incomplete mathematical drafts” may have given occasion to the misunderstanding of this principal idea in Marx theory. Engels, who states this in the preface, sought the collaboration of his friend Samuel Moore who “took on the task of working up this notebook”, since “as a former Cambridge mathematician he is far better equipped to do so”. But Moore was no economist and, in the final analysis, the discussion of these issues entailed economic problems, even expressed in mathematical form. The way in which this part of the work emerged therefore makes it plausible that there was an extensive opportunity for misunderstandings and errors, and that these errors could easily be carried over into the part one on “The law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit”, if only because of the correlation between the two closely connected chapters. [1929 E2: 193]

This is the Marx-passage at issue:

The same laws, therefore, produce a growing absolute mass of profit, which social capital appropriates, [and a falling rate of profit]. [Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chap. 13, as quoted in Grossman (1929 E2: 193-4, n239); the square brackets are Grossman’s. For an alternative translation, see Marx, 1981: 325.]

“The words in square brackets,” Grossman (1929 E2: 194, n239) says, “were wrongly written by Engels or by Marx himself.” After correcting Engels, or Marx, Grossmann reformulates the passage as follows:

The same laws, therefore, produce a growing absolute mass of profit, which social capital appropriates, and at the same time a mass of profit which falls relatively. [1929 E2: 194, n239; emphases are Grossman’s.]

Grossman corrects the Engels-Moore editing “error”—or Marx’s error in his handwriting—by mentally replacing “rate” with “mass” wherever he deems this replacement theoretically required. Grossman’s editor, Rick Kuhn, tells us that Engels, in this context, committed no editing error at all (editor’s note in 1929 E2: 194 n239). As we know for certain since the publication of the critical text edition (MEGA II/4.2: 293), it is solely Marx himself, not his editor Engels, who is responsible for what Grossman treats as an inadvertent substitution of “rate” for “mass.” Because we can discard the conjectures that “rate” was Marx’s writing error or Engels’s editing error, we must conclude that Grossman “corrects” Marx’s intended meaning. He knew, after all, that the alleged writing or editing errors were his own conjectures.

Thus, Grossman’s breakdown theory rests on a revision of Marx’s original text. This revision helps him to avoid a direct confrontation with Marx, it helps him to maintain the appearance of truthful exegetics, and it lays the shaky ground for Grossman’s theory of breakdown. When correcting the “distortions” resulting from Engels’s editing error, or Marx’s presumed writing error, it is actually Grossman who distorts Marx’s reasoning; and Grossman necessarily depends on this distortion when defining his breakdown criterion.[5]

Let me return to the sentence of Marx’s text at issue: “The same laws, therefore, produce a growing absolute mass of profit, which social capital appropriates, and a falling rate of profit” (Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chap. 13, emphases added.) According to Grossman (1929 E2: 193, emphases in original),

The likelihood of error [in the sentence] becomes a near certainty when we consider that it is, unhappily, a matter of a single word, which completely distorts the meaning of the entire argument: the inevitable end of capitalism is ascribed to the relative fall in the rate of profit instead of its mass. Here Engels or Moore has certainly used the wrong term!

Engels or Moore, or even Marx, in Grossman’s opinion, inadvertently replaced “mass” with “rate,” thus ushering in a long tradition of misunderstandings in the literature on Marx’s theory of crises.

Only a single word, “rate,” stands in the way. But it only apparently stands in the way, says Grossman, since it actually must be read as “mass.” An invented misprint or editor’s error thus comes to Grossman’s help, and the likelihood of an editing error turns, in his view, into near certainty when we consider that it is only a single word at a particular place where this error occurs. But in a philological sense, in the sense of establishing a critical version of the text, this does not hit the mark. As Grossman himself is aware, numerous passages in Marx’s writing, not just a single word, must be mentally rewritten.

Actually, Marx does not deal with the question of the inevitable end of capitalism, either at this point or in Capital vol. 3, chapter 13, as a whole. He analyzes the issue that the factors affecting the movement of the rate of profit also affect the mass of profit. Among other things, he shows that the rate of profit can fall even if the mass of profit increases. If Marx wants to show this, if this is a research question of his, then Grossman’s correction can only be grotesque. Grossman heavily distorts Marx’s argument. For Grossman, Marx’s question is about the absolute and relative growth of the mass of profit. Marx himself, however, identifies the common causal factors that affect the movement of the rate of profit on the one hand and the mass of profit on the other. The correction urged for by Grossman is inappropriate; it is a “correction” of what is actually correct by means of exegetical and theoretical distortion.

To repeat, Grossman objects to Marx’s statement that “[t]he same laws, therefore, produce a growing absolute mass of profit, which social capital appropriates, and a falling rate of profit.” At first sight, Grossman’s objection is surprising, since his own Table 2 supports, rather than refutes, Marx’s point. Given that Table 2 exhibits Grossman’s persevering endeavours to extend Bauer’s scheme from only 4 to as many as 35 periods of observation, and given his intimate acquaintance with his own calculations and his general algebraic presentation of the logic behind the table (1929 E2: 185), it is highly improbable that he was unaware that his calculations support Marx’s point.

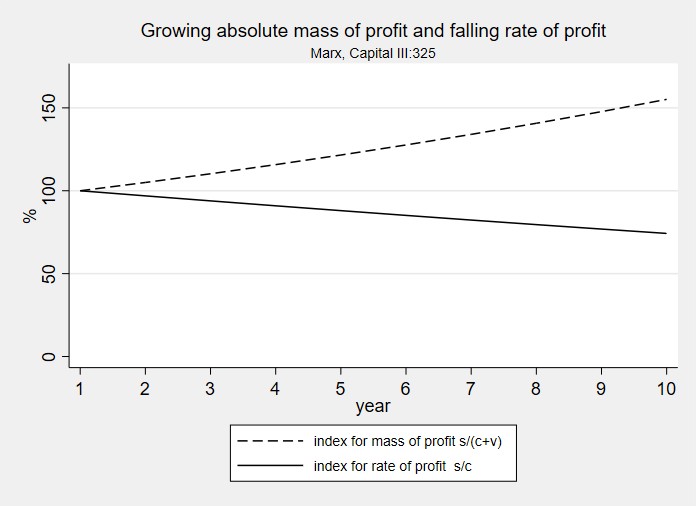

4. Growing Mass of Profit and Falling Rate of Profit: Confronting Grossman’s Main Text with the Implications of His Own Scheme

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the rate of profit and the mass of profit in the Bauer-Grossman scheme throughout its first ten years. The series come from Grossman’s Table 2, which I recalculated using the algorithm in Kliman’s spreadsheet (Oct. 7, 2021b). The rate and mass of profit are both expressed as time-series indexes (percentages of initial values). This allows us to depict the divergent development of the two time-series and the inverse relationship between their trends.

Figure 2. Mass and Rate of Profit

In Figure 2, while the mass of profit increases, the rate of profit falls, thus illustrating Marx’s argument. By presenting Figure 2, I am not assuming that the Bauer-Grossman scheme is in any sense correct. My point is rather that Grossman’s Table 2 supports Marx’s argument, whereas this same argument is rejected in Grossman’s text.

This is not the only case in which his main text contradicts his schematic-statistical calculation or vice versa. But in The Law of Accumulation, it is certainly the most important one.

Immediately after suggesting that Engels or Moore distorted Marx’s meaning by replacing “mass” by “rate,” Grossman commented (1929 E2: 194):

Now, although there are the closest connections between the falling rate of profit and the mass of profit, these two words represent two entirely different words in theory. Several writers like Charasoff, Boudin and others felt that the central point of Marx’s theory lay there. But they could not establish that the breakdown of the capitalist system necessarily follows from Marx’s law of value, because they only ever referred to the fall in the rate of profit.

Here again, Grossman starts with the capitalist system’s breakdown as an established conclusion. He refrains from discussing the point that neither reliance on the rate of profit, nor reliance on the mass, will help to derive capitalism’s breakdown from Marx’s theory of value. Grossman never accepts the burden of proving that it was indeed Marx’s intention to derive the system’s breakdown. For Grossman, the theory of accumulation and the theory of breakdown are one and the same. He is surprised that he is the first to have drawn this conclusion (1929 E2 :190), and he is surprised to be the first to have explicitly concluded that accumulation is doomed to self-destruction.

As for his claim that breakdown can, in value terms, be derived from the decline in the mass of profit, rather than from the decline in the rate, there is Andrew Kliman’s demonstration, having the status of mathematical proof, that Grossman’s schematic-statistical analysis is physicalist—and is therefore not merely unconnected to Marx’s theory of value, but even in contradiction to it.[7] Whether the rate or mass of profit takes the front seat, Grossman’s scheme is driven by physical stuff.[8]

5. The Rate of Profit as “a Pure Number”: Grossman’s Res Cogitans

Contrasting the rate and the mass of profit, Grossman introduces an opposition between a pure number and a real system (1929 E2: 194, emphasis in original):

How could a percentage, like the rate of profit, a pure number, lead to the breakdown of a real system? As if the boiler of a steam engine could explode because the pressure gauge goes too high!

As a pure number, he suggests, the rate of profit has no reality whatsoever, whereas the system itself is said to be real. Thus, the rate of profit and the system itself reside in different ontological spheres, akin to Descartes’ rigorously exclusive dichotomy of res cogitans versus res extensa.[9]

Note that the framing of the choice has been changed (a pure number versus a real system is different from rate versus mass). The reason for this change is obvious. Grossman’s objection to the rate of profit is that it is merely a number, but the same objection can be lodged, and with equal right, against the “relative mass of profit.” Here as well, the mass of profit is a number (actually, a sum of the profits of all firms and departments at the level of total society). And even more, the “relative mass” is a ratio, which therefore must content itself with having the same poor methodological and ontological status as the rate of profit. Thus, rate and mass of profit share the common fate of unreal pure numberness.

The following point can be made against the opposition between a pure number and a real system. The system, as an ensemble of functionally interdependent relations, some of them in antagonistic tension against each other, is an analytic construct. As such, it is as real or as unreal as the rate-of-profit-as-a-pure-number. In the same way and to the same degree, it is as powerless as the numberness of the rate of profit. Yet as an analytical construct, the “system” can be a valid concept; that is, it must affirm itself as empirically correct.

Now to the issue of the rate of profit as a pure number. The rate of profit is a practical category at the surface of bourgeois society. It serves as an indicator that guides managerial decisions, the decisions of individual capitalists (firms) made in the world of their economic experience. In no way it is, as Grossman suggests, the “gauge of the engine’s boiler” that indicates the engine’s imminent breakdown. Grossman’s metaphor turns on the presence of an outside observer, obviously an erudite Marxist,[10] who is interested in the breakdown of the engine. The metaphor does not address the practical perspective of the capitalists.

This is, however, what it must do. As a guiding criterion for investment decisions, the past, current, and prospective rates of profit have practical reality that can be empirically tested. Of course, what have practical reality are not the numbers themselves but the actions of capitalists that are driven by reading and interpreting these numbers. The firm’s rate of profit, compared to the rate of its competitors, will serve as a “gauge” that will make the firm aware of the danger that its level of profitability is not competitive. The management knows from its experience that the firm’s existence is threatened if its rate of profit, compared to the rivals’ rate, is too low for too long a time. In this sense—far from being a mere number—the rate of profit has a practical reality.

6. The Bauer-Grossman Schemes’ Causal Misspecifications

Grossman tends to forget that levels of analysis (firm, department, total economy) and structure, process, and action must be kept separate. As a category of practical action, the rate of profit resides at the individual level. It is at this level where the direction of causal relationship runs from surplus-value to accumulation (s → acc). In an economy without credit, as modelled by the schemes, surplus-value must have been extracted before it can be invested. However, there may be a line of reasoning in favor of Grossman’s specification.

Even at the individual level, we find the opposite direction, ACC → s —with “ACC” now written in capital letters—at least as soon as we take the production of extra-surplus-value into consideration.[11] A single capitalist who introduces a technical innovation must invest a minimum amount of capital for her investment to be beneficial, for it to earn her some extra profit. The size of this minimum is co-determined by the rates of accumulation at the societal level and at the level of the innovator’s industry (here, the rate of accumulation has the status of a so-called context variable). In this case, at the societal (total-economy) level and the department or industry level, we have the rate of accumulation as a pregiven magnitude that the individual innovating capitalist must respect. If the individual capitalist fails to extract the minimum amount of surplus-value, she runs the risk of perishing in the competitive process.

Thus, we are confronted with a multilevel situation. If we consider the situation within the world of reproduction schemes, and at the level of an individual capitalist, surplus-value must have been extracted before it can be invested, and surplus-value can only be extracted in the current period if, in the previous period, there was a minimum amount of surplus-value extracted that is large enough for investment. This minimum amount, in turn, is determined, among other factors, by the rate of accumulation at higher levels of aggregation (industry, department, total economy).

Note that the above comments on causal relationships refer to the world of reproduction schemes, not to the world of empirical economies. Schemes in the Bauer-Grossmann tradition do not recognize credit-financed investments. It is true that Grossman was a highly respected expert on the organization of credit in the Kingdom of Poland (Kuhn 2007: 87-8), but, in the world of reproduction schemes, he remained in the tradition that abstracted from the role of lending capital. All I want to do here is to point to a line of reasoning that—in a world of schemes without credit—could be put forward in defense of Grossman’s causal specifications.

Yet in all these cases mentioned above, the driving force is the intentional, rate-of-profit-guided pursuit of profit by the capitalists, and the moving rate of accumulation at the societal level is the unintended result of the individual actions of the firms. In most contexts, however, Grossman on the contrary favors the conception in which the rate of accumulation is pregiven. Andrew Kliman offers analyses of where and why Grossman’s specification of causal relationships is wrong (e.g., Kliman 2024).

7. The Bauer-Grossman Schemes as Prescriptive Schemes of Centrally Planned Capitalism, Socialism

The major reason that Grossman preferred to conceive of the rate of accumulation as pregiven is implicit in the Bauer scheme,[12] adopted by Grossman. Bauer’s scheme is a prescriptive scheme for a centrally planned capitalism—or, what amounts to the same thing, a centrally planned socialism—in which the priority of Department I, the growth of the organic composition of capital, and the setting of the rate of accumulation are all political imperatives to be implemented by the state.[13]

Figure 3. Otto Bauer’s Prescriptive Scheme of Accumulation

As a member of a military think tank in the Austrian War Ministry, Grossman—by his expertise in analyzing official statistical data—contributed to the management of the Austrian war economy during WWI (Kuhn 2007: 87). This is where he gained experience in directive state intervention by command.

There is no need to decide whether Grossman was a full-blown Stalinist or, as Rick Kuhn suggests,[14] a political Stalinist with his own positions on economic theory, to understand why he was not at all reluctant to import the idea of the predominance of Department I in capitalist development. Bauer, the “neo-harmonist,” and Grossman, the almost-Stalinist and unwavering supporter of the Soviet Union, can live together in harmony when it comes to installing the priority of Department I —despite Grossman’s hostility to Bauer’s “neo-harmonism.”

We find Bauer’s planning prescription in the planning doctrines of “real socialism” as well:

One requirement of the law of the priority development of Section I is that within Section I, those branches that produce the means of production for the production of means of production must grow faster than those that produce the means of production for the production of means of consumption.[15] [Huber 1963: 63; translation by MR]

8. Looking Again at Grossman’s Table 2: Misspecification of Causal Relationships

Continuing my line-by-line reading of pages 193-95 of Grossman (1929 E2), I return to his decision to replace the rate of profit with the relative mass of profit. He disregards the profit rate’s meaning as an action-guiding measure in the capitalists’ economic experience; then he says that the true functional task of this rate of profit must be the monitoring of capitalism’s breakdown; and then, finally, he laments that this rate is not up to the task:

In fact, from Table 2 we see that the capitalist system can exist, despite the fall in the rate of profit, and that the eventual breakdown in year 35 has nothing to do with the fall in the rate of profit as such. Why the system can survive in year 34 with a rate of profit of 9.7 percent, and why it then breaks down in the following year, when the rate of profit is 9.3 per cent, is not explained. The problem is only comprehensible when we link the breakdown not to the rate of profit but to its mass. “Accumulation depends,” Marx writes, “not only on the rate of profit but on the amount of profit.” [Grossman 1929 E2: 194; emphases are Grossman’s.]

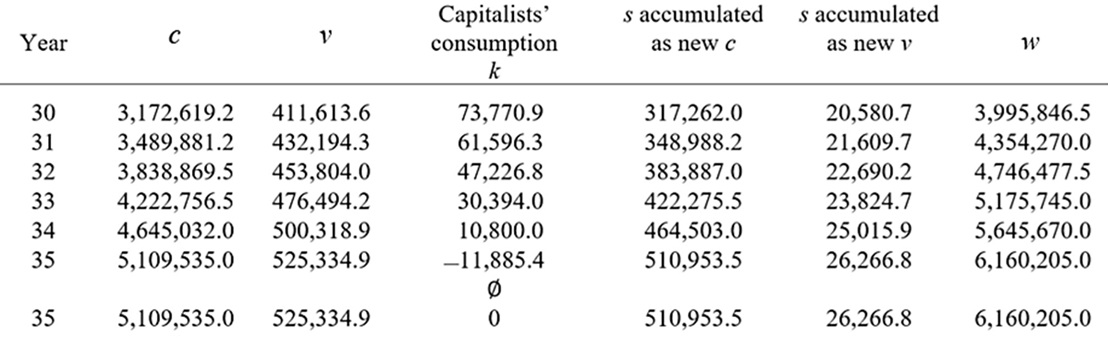

Table MR-1a. Recalculation of Grossman’s Table 2, Part 1[16]

(results selectively presented for Years 30-35)

Figure 4. Grossman’s Original Table 2 (Grossman 1929 G1: 119)

In Grossman’s original Table 2, the negative value for k in Year 35 is replaced by the symbol ∅. This is a fig leaf to cover up the nakedness of negative capitalist consumption, which is certainly not an immediately obvious breakdown indicator. ∅, the empty-set symbol, can be understood to mean that the value cannot be computed by the algorithm that drives Table 2, up to Year 34. As we see in Figure 4, in his calculation for Year 35, Grossman implicitly replaces “∅” by the numerical value zero, “0”—since ∅ is not a number, he actually adds 0 as the value of k when computing the total value of the annual product (Jährlicher Produktenwert)—thus avoiding the question of whether a deterministic algorithm that produces nonsense after some iterations can be correct.

(results selectively presented for Years 30-35)

In Year 35, Grossman’s Table 2 displays the capitalists’ misery. They figure as Weberian Calvinists, forgoing consumption for investment purposes, accepting the exogeneous predestination of the scheme’s mortifications—despite Grossman’s Marxist attack on Weber’s Thesis on the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[17] Year after year, they invest a greater portion of their profit until the bitter end, draining out their personal consumption budget. In Year 35, there is “nothing left to lose,” as we see in column “k” that reports the scheme’s results for the capitalists’ consumption. The capitalists’ death from starvation is Grossman’s proof of the system’s breakdown, but, as we can see in his Table 2, the rate of profit is completely unaffected by this process. The breakdown emerges as a palpable fact only if we “link the breakdown not to the rate of profit but to its mass.” This “mass” turns out to be the capitalists’ breadbasket, which is getting smaller and smaller until it becomes empty in Year 35, and, after Year 35, becomes nothing but a basket full of debts. In Table 2, k’s sudden drop into negative values visualizes this collapse.

Grossman offers supposed textual evidence that his analysis is in line with Marx’s reasoning. First, he quotes a phrase from Marx’s 1861-1863 Economic Manuscript: “Accumulation depends,” Marx writes, “not only on the rate of profit but on the amount of profit’” (Grossman 1929 E2: 194, quoting Marx 1989c: 165).

Here is the larger context in which the phrase is contained:

Thus with the same expenditure of revenue accumulation is the result of the rise in the rate of profit (but accumulation depends not only on the rate of profit but on the amount of profit); with a constant rate of profit accumulation is the result of decreasing expenditure, which is however assumed by Ricardo to occur because of the reduced price (whether this is brought about by machinery or foreign trade) of “commodities on which revenue was expended.” [Marx 1989c:165; emphases in original.]

Marx is discussing the investment of revenue in Ricardo’s oeuvre. There is no indication whatsoever that, in this context, Marx is dealing with Grossman’s suggestion to replace the fall in rate of profit by the relative fall in the mass of profit. In scrutinizing Ricardo’s arguments, Marx asks how changes in the expenditure of revenue influence accumulation: what happens if we keep the rate of profit constant; if we let it rise; or if we let it decline? In this context, Marx mentions the fact that accumulation (the amount of profit accumulated as capital) depends both on the rate of profit and on the mass of profit.

Obviously, successful accumulation, as studied by Ricardo and critically restudied by Marx, rather than accumulation’s inevitable failure—which is Grossman’s obsession—is the object of investigation here.

Second, Grossman (1929 E: 194) quotes a most of a sentence in Capital, volume 1:

All the circumstances that determine the mass of surplus value operate to determine the magnitude of accumulation. [Marx 1976b: 747; emphasis is Grossman’s.]

Here is the larger context of Marx’s statement:

If we assume the proportion in which surplus-value breaks up into capital and revenue as a given factor, the magnitude of the capital accumulated clearly depends on the absolute magnitude of the surplus-value. Suppose that 80 percent of the surplus-value is capitalized and 20 percent is eaten up, then the magnitude of capital accumulated will be £2,400 or £1,200, according to whether the total amount of surplus value was £3,000 or £1,500. Hence all the circumstances that determine the mass of surplus-value operate to determine the magnitude of the accumulation.

Note that the magnitude of accumulation is the dependent variable here, while in the Bauer-Grossman scheme it appears as a pregiven independent variable based on a pregiven rate of accumulation. This is the fundamental reason why the passage offers no support whatsoever for Grossman’s thesis. Accumulation, Marx says, is determined in part by the amount of surplus-value (profit) available to the capitalist investors. Factors that determine the amount of surplus-value therefore co-determine the magnitude of accumulation. In this line of reasoning, the amount of surplus-value has the role of an intervening variable. Obviously, the causal direction is (factor 1, factor 2, factor 3, etc.) In the Bauer-Grossman scheme, this causal chain is reversed. Thus, while the passage cannot support Grossman’s argument, it can be put forward as exegetical evidence against the Bauer-Grossman scheme’s causal assumptions.[18]

Third, later in the same paragraph, Grossman (1929 E2: 195) writes:

Ideas cannot destroy a real system. This is why Sombart and Bauer could not understand Marx’s theory of breakdown. Matters are different if value and thus also the mass of profit are conceived of as a real magnitude. In this case the breakdown of the system has to follow from a relative fall in the mass of profit, even if it nevertheless can and does increase in absolute terms. The fall in the rate of profit is thus only an index which registers the relative fall in the mass of profit. A falling rate of profit is only important for Marx because it is identical with a relative decline in the mass of surplus value in the sense just outlined: “The law of a progressive fall in the rate of profit, or the relative decline in the surplus labour appropriated.”

The interior quotation at the end of Grossman’s statement comes from Capital, volume 3. In context, it reads:

The law of a progressive fall in the rate of profit, or the relative decline in the surplus labour appropriated in comparison with the mass of objectified labour that the living labour sets in motion, in no way prevents the absolute mass of labour set in motion and exploited by the social capital from growing, and with it the absolute mass of surplus labour it appropriates; any more than it prevents the capitals under the control of individual capitalists from controlling a growing mass of labour and hence of surplus labour, this latter even if there is no increase in the number of workers under their command. [Marx 1981: 322-23.]

In his reference to Marx’s text, Grossman truncates the opening sentence—“The law of a progressive fall in the rate of profit, or the relative decline in the surplus labour appropriated in comparison with the mass of objectified labour”—by eliminating the passage I have emphasized. This truncation helps to create the impression that “the relative decline in the surplus labour appropriated”—which Grossman presents as a completed sentence, contrary to Marx’s text—delivers a sufficient assessment of the fall in the rate of profit. This amounts to Grossman pilfering Marx’s support for his distortion of Marx.

In the passage from Capital, volume 3, Marx repeats his conception of a progressive fall in the rate of profit as “the relative decline in the surplus labour appropriated in comparison with the mass of objectified labour that the living labour sets in motion.” The “mass of labour” he talks about is not the “mass of surplus labour,” it is rather the “mass of objectified labour”; that is, Marx talks here about constant capital. And Marx employs his usual conception of the rate of profit as the ratio of surplus value (profit) to capital advanced.

To look more closely at what Marx says, let us take it bit by bit.

(1) Appropriated surplus value declines relatively, where “relatively” means: compared to the capital advanced (constant capital, variable capital).

(2) The absolute mass of objectified labour, that is, the absolute mass of advanced constant capital, set in motion by living labour, can grow even when the rate of profit declines.

(3) The absolute mass of appropriated surplus-value can grow even when the rate of profit declines.

Statements (1) to (3) refer to the level of the total economy. The following statements, (4) to (6), refer to the level of the individual capitalists (i.e. the firms):

(4) Capitals under the control of individual capitalists can control a growing mass of labour even when the rate of profit declines.

(5) A growing mass of labour implies a growing mass of surplus labour.

(6) The mass of surplus labour can grow even if there is no increase of workers under the capitalist’s command.

None of the statements, (1) thru (6), and no combination of them, supports the demand for the “correction” that Grossman (1929 E2: 195) proposes: “Matters are different if value and thus also the mass of profit are conceived of as a real magnitude. In this case the breakdown of the system has to follow from a relative fall in the mass of profit, even if it nevertheless can and does increase in absolute terms.”

Magnitudes are real, ratios are not. I discussed this point above. Yet Grossman’s law of the relative fall in the mass of profit is itself based on the ratio of the mass of profit to the constant capital invested. I will return to this point in section 9 below.

Fourth, Grossman (1929 E2: 195) immediately adds the following:

Only in this sense is it possible to maintain that with a falling rate of profit the system breaks down, for the rate of profit falls because the mass of profit declines in relative terms. “The fall in the rate of profit thus expresses the falling ratio between surplus-value itself and the total capital advanced.” [The interior quote is on Marx 1981: 320; emphases are Grossman’s.]

At first sight, the sentence of Marx’s text that Grossman quotes here states something obvious. After all, Marx seems to do nothing but restate the definition of the rate of profit. In Grossman’s view, however, the phrase “surplus-value itself” indicates the importance of understanding surplus-value as a mass of value, since only as a magnitude it can claim to be real. And only as something real can its decline produce capitalism’s breakdown. Once again, the breakdown thesis is presupposed as an established given, and Marx’s text is adapted so that it can serve to confirm the thesis.

Yet in Marx’s text, the word “itself,” in the phrase “surplus-value itself,” stresses the point that surplus-value or profit can be understood in its yet-undifferentiated unity. The law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit, Marx says, is independent of the profit’s differentiation into different categories of revenue. Therefore, at the level of the total economy, undifferentiated profit equals surplus-value, and surplus-value, as a magnitude, functions as the profit rate’s numerator:

We are deliberately putting forward this law [of the tendential fall in the rate of profit] before depicting the decomposition of profit into various categories which have become mutually autonomous. The independence of this presentation from the division of profit into various portions, which accrue to different categories of persons, shows from the start how the law in its generality is independent of that division and of the mutual relationships of the categories of profit deriving from it. Profit, as we speak of it here, is simply another name for surplus-value itself, only now depicted in relation to the total capital, instead of to the variable capital from which it derives. The fall in the rate of profit thus expresses the falling ratio between surplus value itself and the total capital advanced; it is therefore independent of any distribution of this surplus-value we may care to make among the various categories. [Marx 1981: 320.]

Marx is arguing that the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit is general, in the sense that it includes all subcategories of profit into the numerator of the rate of profit. Grossman, by contrast, turns this argument into exegetical evidence for an exalted ontological status of the rate’s numerator.

But Grossman’s argument requires more than assuming that the surplus-value in the rate of profit’s numerator is a “mass.” After all, on any definition of the rate of profit, it cannot be anything else. His argument depends on the surplus-value’s additional qualification as a “real magnitude”:

It is only this relative decline in the mass of profit (in surplus value, in the mass of surplus value) as a real magnitude, rather than the fall in the rate of profit, that engenders the “conflict between the extension of production and valorization.” [Grossman 1929 E2: 195; the interior quote is on Marx 1981: 320; both emphases are Grossman’s.]

Beyond any doubt, Marx’s text offers no support whatsoever for Grossman’s reasoning.

9. Grossman’s Scheme for “Constant Capital Accumulation” in “The Change in the Original Plan for Marx’s Capital and Its Causes”

My line-by-line commentary on pages 193-195 in Grossman’s The Law of Accumulation and the Breakdown of the Capitalist System is now finished. To further clarify his conception of the “relative fall in the mass of profit,” I now take up his example in “Die Änderung des ursprünglichen Aufbauplans des Marxschen ‘Kapital’ und ihre Ursachen” (Grossmann 1929 G3). Its English translation appeared under the title “The Change in the Original Plan for Marx’s Capital and Its Causes” (Grossman 1929 E1).

Grossman writes:

The law itself, however, is a self-evident consequence of the labour theory of value if accumulation takes place on the basis of a progressively higher organic composition of capital. “The fall in the rate of profit thus expresses the falling ratio between surplus value itself and the total capital advanced; it is therefore independent of any distribution of this surplus value we may care to make among the various categories.” And, in fact, if one starts with the formula c + v + s [= C] and supposes a yearly increase of constant capital c of 10% and of variable capital v of 5%, it follows simply and clearly that, with accumulation and as a consequence of the rising organic composition of capital, once a certain level is reached, the tempo of accumulation becomes ever smaller, despite an initial acceleration, and accumulation eventually becomes impossible. The mass of surplus value is insufficient to sustain growth at the level required by the rapidly increasing constant capital. [Grossman 1929 E1: 152-3; bracketed insertion by Grossman’s editor. The interior quote is on Marx 1981: 320; emphasis is Grossman’s.]

Here, Grossman again cites the passage in Capital, volume 3, discussed above (Marx 1981: 320), in which Marx develops the reasons why undifferentiated profit, i.e. profit before it is separated into several mutually independent subcategories, constitutes the profit rate’s numerator. Whatever the distribution of total profit among its subcategories may be, Marx says, its sum will be the same, and it is this sum that must enter as the numerator into the rate of profit. But Grossman turns this passage into exegetical evidence for the conclusion that, as the organic composition increases, accumulation will finally break down. Again, the breakdown appears like a rabbit being pulled out of a hat.

The numerical example Grossman provides here—“yearly increase of constant capital c of 10% and of variable capital v of 5%”—must be read against the backdrop of Table 2 of his Law of Accumulation. By implication, Grossman claims that the reproduction scheme presented in his Table 2 accurately renders the passage of Marx’s from which he quotes, which it does not: in Grossman’s scheme, the growth of constant capital is said to be pregiven; it is defined exogenously,[19] rather than being the result of ongoing extraction of surplus-value; and the growth of surplus-value is, by assumption, too slow to satisfy the demand for additional constant capital. The “rapidly increasing constant capital” grows at precisely the speed that Grossman dictates, by means of his scheme’s assumptions, and the growth of surplus-value lags behind the growth of c to the precise extent dictated by the difference in the growth rates (10% for constant capital, 5% for surplus-value).

Grossman (1929 E1: 153) then considers the following three cases:

1 200,000 c + 100,000 v + 100,000 s

2 1,000,000 c + 100,000 v + 110,000 s

3 4,600,000 c + 100,000 v + 120,000 s

From Case 1 to Case 2, constant capital increases by 400%; from Case 2 to Case 3, the increase amounts to 360%. By comparison, surplus-value grows by 10% from Case 1 to Case 2, and by 9.1% from Case 2 to Case 3. The organic composition of capital in Case 1 is 2 (200,000 c / 100,000 v), in Case 2 it is 10 (1,000,000 c / 100,000 v), and in Case 3 it is 46 (4,600,000 c / 100,000 v). Leaving aside the question of whether the growth assumptions for constant capital, surplus-value, and the rate of exploitation are mutually compatible, I address the question of what Grossman means by “case.”

Grossman (1929 E1: 153) goes on to interpret his example as an illustration of why the economy must eventually break down:

In the first case, constant capital c can be accumulated at 50% of its initial size, if surplus value is used solely for the purposes of accumulation. In the second case, with a significantly higher organic composition of capital and even though the rate of surplus value has grown, the expanded mass of surplus value of 110,000 s barely suffices to increase the initial capital by 10%. Finally, in the third case, a mass of surplus value of 120,000 barely increases the initial capital by 2½%. It is easy to calculate that, as the organic composition of capital rises more, a point must come when it is impossible for accumulation to continue. That is Marx’s law of breakdown—“the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation”. [The interior quote is on Marx 1976: 798; emphasis omitted by Grossman]

(in “The Change in the Original Plan for Marx’s Capital and Its Causes”)

Table MR-2 explicates the information given by Grossman (1929 E1: 153) quoted above. The initial values of c, v, and s in Year 1 of Case 1 are those of his example. They are identical to the initial values in Table 2 of Grossman’s book (1929 E2: 136). Given these initial values and Grossman’s (1929 E1: 153) assumptions, the accumulation algorithm is now fully defined. Regarding c and v, it produces a scheme that, by the logic of its process and by its numerical initial assumptions, is identical to the Bauer-Grossman scheme in Table 2 of his book. Accordingly, the rows in Case 1 representing the years 34 through 36 report the values for constant capital, variable capital and surplus-value around the breakdown point.

Following Kliman’s conception, we can identify the breakdown point as the point at which the supply-demand ratio is 100% (or smaller). In Case 1, Year 34, the economy’s output is 5,645,670. This is the supply side of the balance. In Year 35, the sum of c + v is 5,634,870. This is the productive demand side of the balance. Thus, the balance ratio is (5,645,670/5,634,870) × 100% = 99.8%. Since the balance is calculated by relating this year’s supply to the following year’s demand, Table MR-2 reports the respective data for one additional year after the breakpoint year.

Case 2 also starts with the values that Grossman has specified: c = 1,000,000; v = 100,000; s = 110,000. In Year 1 of Case 2, we see that the balance ratio is around 100%. Thus, Case 2 describes an economy just about to exhale its soul. Within two iterations further, the offered productive supply is too small to satisfy the productive demand. Case 3—with its starting values c = 4,600,000; v = 100,000; s = 120,000 and an organic composition as high as 46—is the post-mortem trajectory of an economy that has lost its life long ago.

In all three cases, the organic composition grows by 4.8 percent per year. Obviously, it is not Grossman’s intention to present a realistic example.[20] His example is rather designed as a drastic exaggeration of the self-destructive features of capitalist accumulation, where the growth of organic composition is the driving destructor.

Nonetheless, Grossman’s suggestion, to calculate the development of c, v, and s by applying the respective growth assumptions, actually refers only to Case 1, an economy that still has a time to live on. Cases 2 and 3 designate particularly significant points in an economy’s development: an economy that is just about to give up its soul; and a non-economy, where accumulation is impossible. The growth assumptions are inapplicable to these latter cases, since the economy is either just about to break down or has already broken down.

While Case 1 in Table MR-2 offers identical results to Grossman’s Table 2 (1929 E2: 136)—as far as c, v, and s are concerned—there is one significant difference between the two forms of presentation. Table MR-2, based on the example in “The Change in the Original Plan for Marx s Capital and Its Causes,” treats surplus-value as an undifferentiated mass, whereas Table 2 in Grossman’s book allocates one part of the surplus-value to accumulation, and the remaining part to capitalists’ consumption, with this allocation being driven by a pregiven rate of accumulation. In his book, there is a breakdown point that immediately catches the eye: the exhaustion of the capitalists’ revenue, leaving them without any means of consumption. By contrast, in his “The Change in the Original Plan,” Grossman merely offers the assertion that “[it] is easy to calculate that, as the organic composition of capital rises more, a point must come when it is impossible for accumulation to continue.” By presenting his three cases, he endeavours to lend highest plausibility to this statement, but he offers no definition of the breakdown point’s exact position in the scheme.

Figure 5. Accumulation of Constant Capital and Supply-Demand Balance

We are informed, however, about what Grossman means by the term “relative mass of surplus-value”; this is the ratio of the undifferentiated surplus-value to the constant capital advanced. He calls this indicator “constant capital allocation”; it measures, in percentage terms, the possible increase of the constant capital advanced, where this possible increase is determined by the mass of surplus-value that has been extracted. In Case 1, this possible increase is 50% (in the German-language original, Grossman inadvertently says 40%); in Case 2, constant capital accumulation amounts to 10%; and in Case 3, Grossman reports a relative mass of surplus-value as low as 2½%.

However, low as it may be, we do not know why it is low enough to signal that the economy is non-viable (see the left-side panel in Figure 5). By contrast, in the right-side panel, the breakdown point is defined, following Kliman’s conception, by the requirement that this year’s supply must be greater than productive demand of the following year (reference line = 100). Obviously, Cases 2 and 3, falling below the reference line, depict non-viable economies.

What appears as the balance-line in Figure 5, right-side panel, is at the same time a line of Grossman’s failure. This line shows an assumption-driven breakdown tendency that—far from being a “natural consequence from Marx’s theory of value”—contradicts it. Given the self-destructive logic of capitalist accumulation, Grossman says, the mass of surplus-value will finally be too small to allow for continuous accumulation at a pregiven rate. All his desperate efforts to squeeze out of Marx’s text that the “fall in the rate of profit” must be replaced by the “fall in the relative mass of profit” are guided by this explanation of breakdown.

10. Concluding Remarks

In the citation below, Grossman (1929 E2: 195) himself inadvertently reveals the secret of his exegetical and interpretative strategy.

Only once we recognize the role of the mass of profit and its relation to the rate of profit, which I have discussed here, will a closer reading of the whole chapter on the tendential fall in the rate of profit lead directly to the conclusion that, in several passages, the wording has been distorted in the direction indicated above. Only in this way can the necessity of the breakdown, that is, the conflict between extension of production, accumulation and valorisation, have been obscured and misunderstood. From this, it is apparent what decisively important insights into the character of value in Marx are, at the same time, also yielded by the theory of breakdown!

Here, Grossman tells us that, as a first step, his own breakdown theory must be read into Marx’s text to eliminate the text’s distortions. And then, now that the text is distortion-free and embellished by Grossman’s ideas—some of which come close to absurdities—the text is a rich exegetical reservoir for Grossman’s “correction” of Marx’s Law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit. Grossman reaps what he sows, and what he sows as a “correction” of alleged textual distortions is itself a distortion of Marx’s theory of value. “From this,” Grossman says, “it is apparent what decisively important insights into the character of value in Marx are, at the same time, also yielded by the theory of breakdown!”

Grossman repeatedly defended himself against the objection that he discarded the role of class struggle; he rejected the allegation that his breakdown theory was“mechanistic,” that it rested on a purely economic process that runs down as if driven by a clock’s mechanism. And indeed, there are numerous passages in his writings where he insists on the role of class struggle and political action, especially so in his exchange of letters with Paul Mattick. However, his scheme-guided theory and his action-oriented reasoning stand side by side without touching each other. They stand in mutual separation rather than interpenetration: as the mis-constructed economic clockwork runs down, the point will come when the clock fails. This is the point when the proletariat’s forceful action, guided and educated by its party, must and will step in.

Grossman is reputed to be a great Marxist. As the title of Rick Kuhn’s (2007) biography indicates, Grossman’s lifetime achievement is said to be nothing less than the “recovery of Marxism.” Does he earn this reputation? Yes, if we apply an operational definition of a “great Marxist.” Recall some of the greatest Marxists to your mind, especially its epitome, the Marxist geographer, then try to find their common traits. A great Marxist is a writer who praises Marx as a genius; who criticizes Marx in the form of praise; who insinuates his own theory into Marx’s work and sells it as the theory of Marx himself; who therefore, now on a par with a genius, successfully sells his own books—and who thus rightfully earns his worldwide reputation.

REFERENCES

Works by Grossman

The letters “G” and “E” following a work’s date of publication indicate its German- and English-language versions, respectively.

[1928 G] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Eine neue Theorie über Imperialismus und soziale Revolution. Zuerst erschienen in Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung (Hrsg. Carl Grünberg), XIII. Jg. Leipzig 1928, S. 141-192. In Grossmann 1971, 113-164.

[1929 E1] Grossman, Henryk. 2013. The Change in the Original Plan for Marx’s Capital and Its Causes. Historical Materialism: 21:3, 138-164. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/ee92debf-1ab9-47a7-a084-cd64af16964a/content .

[1929 E2] Grossman, Henryk. 2021. The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System, Being also a Theory of Crises. Edited and introduced by Rick Kuhn. Translated by Jairus Bananji and Rick Kuhn. Henryk Grossman Works, Volume 3. Brill: Leiden.

[1929 G1] Grossmann, Henryk. 1929. Das Akkumulations- und Zusammenbruchsgesetz des Kapitalistischen Systems (Zugleich eine Krisentheorie). Leipzig: Verlag C.L. Hirschfeld Leipzig http://pombo.free.fr/grossmann29.pdf .

[1929 G2] Grossmann, Henryk. Zweite Auflage. 1970. Das Akkumulations- und Zusammenbruchsgesetz des kapitalistischen Systems. Archiv Sozialistischer Literatur 8. Frankfurt: Verlag Neue Kritik.

[1929 G3] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Die Änderung des ursprünglichen Aufbauplans des Marxschen “Kapital” und ihre Ursachen. Zuerst erschienen in Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus. Jahrgang XIV, 1929. In Grossmann 1971, 9-42.

[1930s, 1940s E] Grossmann, Henryk. 2009. Descartes and the Social Origins of the Mechanistic Concept of the World. In Freudenthal and McLaughlin (eds.) 2009, 157-230.

[1932 E] Grossman, Henryk. 2016. The Value-Price Transformation in Marx and the Problem of Crisis. Historical Materialism: 105-134. http://pinguet.free.fr/grossman32.pdf .

[1932 E] Grossman, Henryk. 2018. The Value-Price Transformation in Marx and the Problem of Crisis. Historical Materialism: 24:1, 2016. Reprinted in Grossman, Works, Volume 1, 2018.

[1932 G1, G2] Grossmann, Henryk. 1932. Die Wert-Preis-Transformation bei Marx und das Krisenproblem. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 1: 1-2, 55-84. https://www.marxists.org/deutsch/archiv/grossmann/1932/xx/wert-preis.htm , http://digamoo.free.fr/grossman1932.pdf .

[1932 G3] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Die Wert-Preis-Transformation bei Marx und das Krisenproblem. In Grossmann 1971, 45-74.

[1932 G4] Grossmann, Henryk. 1932. Die Goldproduktion im Reproduktionsschema von Marx und Rosa Luxemburg (1932). In Festschrift für C. Grünberg, Hrsg. Max Adler u.a. Leipzig: C.L. Hirschfeld. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/adsd/06730/06730-14.pdf .

[1932 G5] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Die Goldproduktion im Reproduktionsschema von Marx und Rosa Luxemburg. In Grossmann 1971, 77-109.

[1934 E] Grossmann, Henryk. July 2006. The Beginnings of Capitalism and the New Mass Morality, Journal of Classical Sociology. https://www.marxists.org/archive/grossman/1934/beginnings.htm . Journal of Classical Sociology. [Written and first published in 1934 as “Die Anfänge des Kapitalismus und die neue Massenmoral.” It is held in the collection “Henryk Grossman,” III-155, of the Archiwum Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Warsaw.]

[1935 E] Grossman, Henryk. 2009. [1935] The Social Foundations of the Mechanistic Philosophy and Manufacture. In Freudenthal and McLaughlin (eds.) 2009: 103-156.

[1935 G] Grossmann, Henryk. 1935. Die gesellschaftlichen Grundlagen der mechanistischen Philosophie und die Manufaktur. Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung 4: 2, 161-231.

[1935-1938 E] Grossmann, Henryk. 2009. Additional Texts on Mechanics. In Freudenthal and McLaughlin (eds.) 2009: 231-238.

[1941 G] Grossmann, Henryk. 1969. Marx, die klassische Nationalökonomie und das Problem der Dynamik. Mit einem Nachwort von Paul Mattick. Frankfurt am Main: Europäische Verlagsanstalt. https://aaap.be/Pdf/Crisis-Theories/Henryk-Grossmann-de-1969-Marx-die-klassische-Nationalokonomie-und-das-Problem-der-Dynamik.pdf .

[1943 G] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Die evolutionistische Revolte gegen die klassische Ökonomie. In Grossmann 1971, 167-213. [The English-language original first appeared as “The Evolutionist Revolt Against Classical Economics,” Political Economy, Vol. LI (1943): 381-522. Translated from English by Joschka Fischer.]

[1971 G] Grossmann, Henryk. 1971. Aufsätze zur Krisentheorie. Archiv Sozialistischer Literatur. Frankfurt: Verlag Neue Kritik.

[2019 E] Henryk Grossman Works, Volume 1. Essays and Letters on Economic Theory, 2019. Edited and Introduced by Rick Kuhn. Brill: Leiden.

[2021 E] Henryk Grossman Works, Volume 3. The Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System, Being also a Theory of Crises. Edited and introduced by Rick Kuhn. Translated by Jairus Bananji and Rick Kuhn. Brill: Leiden.

Works by Marx

Editions of Marx’s works that appear in the list below were consulted when checking references to Marx in Grossman’s texts (as edited by Rick Kuhn) against Marx’s original texts.

MEGA II

Marx, Karl. 1863-1865. MEGA II/4.2: Das Kapital. Ökonomisches Manuskript.1863-65. Teil2. MEGAdigital: http://telota.bbaw.de/mega/ .

Marx, Karl. 1884/85. MEGA II/12: “Das Kapital”, 2. Band, Redaktionsmanuskript 1884/85. Berlin: De Gruyter. MEGAdigital: http://telota.bbaw.de/mega/ .

Marx, Karl. 1890. MEGA II/10: “Das Kapital”, 1. Band, Druckfassung 1890. Berlin: De Gruyter. MEGAdigital: http://telota.bbaw.de/mega/ .

Marx, Karl. 1894. MEGA II/15: “Das Kapital”, 3. Band, Druckfassung 1894. Berlin: De Gruyter. MEGAdigital: http://telota.bbaw.de/mega/ .

MEW 23 (1973). Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels. Marx-Engels-Werke. Band 23: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Erster Band. Berlin: Dietz.

MEW 24 (1973). Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels. Marx-Engels-Werke. Band 24: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Zweiter Band. Berlin: Dietz.

MEW 25 (1973). Karl Marx und Friedrich Engels. Marx-Engels-Werke. Band 25: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, Dritter Band. Berlin: Dietz.

Marx, Karl. 2017. Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Buch I. Der Produktionsprozess des Kapitals. Neue Textausgabe. Bearbeitet und herausgegeben von Thomas Kuczynski. Auf der Grundlage der zweiten deutschen Ausgabe von 1872/73 und der französischen Ausgabe von 1872/75 sowie der Arbeitsexemplare des Verfassers, unter Berücksichtigung der Erstausgabe und der von Friedrich Engels herausgegebenen Ausgaben sowie weiterer handschriftlicher Materialien von Marx und Engels. Hamburg: VSA Verlag.

English-language editions

Marx, Karl. 1976 [1867]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 1, translated by Ben Fowkes, Hammondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1978 [1885]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 2, translated by David Fehrenbach, Hammondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1981 [1894]. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume 3, translated by David Fehrenbach, Hammondsworth: Penguin.

Marx, Karl. 1989c [1905-10. Written 1861-1863] ‘‘Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63” [Notebooks XII-XV] in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Volume 32. New York: International Publishers.

Marx, Karl. 1991a [1905-10. Written 1862-1863] ‘‘Economic Manuscripts of 1861-63” [Notebooks XV-XX] in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Volume 33. New York: International Publishers.

Works by Others

Bauer, Otto. 1912/1913. Die Akkumulation des Kapitals, Teil 1. Die Neue Zeit: Wochenzeitschrift der deutschen Sozialdemokratie 31. Jahrgang. Erster Band. Heft 23: 831-838. https://library.fes.de/cgi-bin/nzpdf.pl?dok=191213a&f=831&l=83 .

Behrens, Fritz. 1956. Grundriss einer Geschichte der Politischen Ökonomie. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

_______. 1963. Zur Theorie der Messung des Nutzeffektes der gesellschaftlichen Arbeit. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Fink, Wolfgang. 2009. (Klassen)kampf der Nationen. Der Streit um Otto Bauer und die Nationalitätenfrage. Études Germaniques 254:2, 329-348. [(Class)-struggle of the Nations. The dispute over Otto Bauer and the nationalities question. Title translated by MR.]

Freudenthal, Gideon and Peter McLaughlin, eds. 2009. The Social and Economic Roots of the Scientific Revolution: Texts by Boris Hessen and Henryk Grossmann. Dordrecht: Springer.

Howard, M. C. and J. E. King. 1989. A History of Marxian Economics, Volume I, 1883-1929. London: Macmillan.

Huber, Gerhard. 1962. Die ökonomische Entwicklung der Rumänischen Volksrepublik. [The economic development of the Peoples Republic of Rumania.] Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Informationen. Herausgegeben von der Leitung des Instituts für Wirtschaftswissenschaften bei der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Heft 24/25.

Kliman, Andrew. 2007. Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency. Lanham: Lexington Books.

_______. 2012. The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession. New York: Pluto Press.

_______. Oct. 7, 2021a. Henryk Grossmann’s Breakdown Model: On the Real Cause of the Fictitious Breakdown Tendency, With Sober Senses. https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/economics/henryk-grossmanns-breakdown-model-on-the-real-cause-of-the-fictitious-breakdown-tendency.html .

_______. Oct. 7, 2021b. The-Bauer-Grossmann-reproduction-scheme-once-rising-productivity-cheapens-commodities04-1221.xls . Linked spreadsheet file. In Kliman, Oct. 7, 2021a.

_______. Jan. 25, 2022. Spreadsheet file attached to personal communication.

_______. Jan. 26, 2022. Personal communication.

_______. Jan. 27, 2022. Grossmann’s Breakdown Model: Responses to Challenges and Questions, With Sober Senses. https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/economics/grossmanns-breakdown-model-responses-to-challenges-and-questions.html .

_______. May 27, 2022. Review-essay: The End of Capitalism: The Thought of Henryk Grossman, With Sober Senses; https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/economics/review-essay-the-end-of-capitalism-the-thought-of-henryk-grossman.html .

_______. Sept. 13, 2023. Mathematics of Growth and Breakdown in the Bauer-Grossman Model. In: Online Class Series on Grossman’s Breakdown Model and Theory: Sept. 24 & Oct. 8, Led by Andrew Kliman, With Sober Senses. https://marxisthumanistinitiative.org/economics/20373.html .

_______. Oct. 11, 2024. Grossman’s Breakdown Theory versus Marx’s Value Theory. Unpublished ms. (under submission).

Kuhn, Rick. 2006a. Henryk Grossman bibliography. Prepared by Rick Kuhn. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/ee73b276-ebe0-4523-905f-b1291ab118/content .

_______. 2006b. Introduction to Henryk Grossman s critique of Franz Borkenau and Max Weber. Journal of Classical Sociology. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/9ba57b31-e527-44b8-8f86-7d9f84fbef73/content .

_______. 2007. Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

_______. 2009. Henryk Grossman: A Biographical Sketch. In Freudenthal and McLaughlin (eds.) 2009, 239-256. http://digamo.free.fr/grossbh2.pdf .

_______. 2016. Introduction to Henryk Grossman, The Value-Price Transformation in Marx and the Problem of Crisis, Historical Materialism 24:1, 91-103. http://digamoo.free.fr/kuhn16.pdf .

NOTES

[1]. I thank Andrew Kliman for his corrections and helpful suggestions. For any remaining errors or deficiencies, the responsibility rests with me.

[2]. See the list of Kliman’s writings on Grossman at the end of this article.

[3]. The default version assumes that the initial value of physical means of production is 2, the growth rate of physical means of production is 10%, the initial value of new value added is 2, the growth rate of new value added is 5%, the rate of exploitation is 100%, and the constant rate of accumulation is 25%.

[4]. The supply-demand imbalance in terms of value reflects their imbalance in physical terms since the ratio of supply to productive demand in terms of value is necessarily equal to their ratio in physical terms.

[5]. „Und doch: Großmanns Theorie ist zuletzt nur zu stützen, indem er sie auf einem ‚Irrtum‘ Engels‘ beim Abschreiben der Marxschen Manuskripte aufbaut.“ (Behrens 1956: 265). [“And yet: Grossmann’s theory can ultimately only be supported by basing it on an ‘error’ made by Engels when copying Marx’s manuscripts.”; translation by MR.]

[6]. Note that Grossman rephrases Marx’s law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit as “law of the relative fall in the rate of profit” (my emphasis).

[7]. Kliman (Oct. 7, 2021a).

[8]. For definition of the term “physicalism,” see citations in index entry on p. 227 in Kliman (2007).

[9]. Grossman (1930s, 1940s E).

[10]. Grossman (1935 and 1935 E.)

[11]. By 1941 at the latest, 12 years after the publication of Die Akkumulation des Kapitals, Grossman was well aware of the category “extra-surplus-value.” See Grossmann (1941 G: 79).

[12]. Bauer, Otto (1912-13: 831-838).

[13]. For the concept of organized capitalism, see Howard and King (1988, vol. I: 273). For Bauer’s special brand of nationalism and social Darwinism, see Fink (2009).

[14]. See index entry “Stalinism and Grossman” in Kuhn 2007.

[15]. For a cautious critique of the law of the priority development of Section I as a guiding planning principle, see Behrens (1963: 174): “The point is that the population’s consumption structure must determine the structure of production and not the other way around. Of course, production remains paramount. But this formulation is far too global. It is at best acceptable as a rough planning guideline. Prosperity depends not only on the quantity of use values produced. It additionally depends on whether the products meet the wishes of consumers, i.e. at given prices there must be neither excess purchasing power nor must there be a build-up of planned excess stocks.”

[16]. To distinguish my own tables from those of Grossman’s book, I am affixing my initials, MR, to my tables’ numbers.

[17]. Kuhn (2006b).

[18]. For the misspecification of causal relationships in Grossman’s schemes, see especially Kliman (Oct. 11, 2024).

[19]. Kliman (Oct. 7, 2021).

[20]. Kliman, Andrew (2012: 133): “The technical and organic compositions of capital have risen almost continuously, and rather rapidly, during the last six decades [1947-2007]. Their average annual growth rate between 1947 and 2009 was 1.7 percent.”

Be the first to comment