A major dispute over the causes of the latest capitalist economic crisis, and how to respond to it, has erupted in the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI), an orthodox Trotskyist organization. Its largest section, the Socialist Party of England and Wales (SP(E&W)), is one of the remnants of the Militant Tendency that was expelled from the British Labour Party in the early 1980s.

A growing group of dissidents in the CWI contends that the organization pays lip service to the crisis theory of Karl Marx, but actually bases itself on the underconsumptionist theory of Monthly Review and on Keynesianism. The leadership acknowledges that it rejects what it calls the “dogmatic theory that the tendency of the rate of profit to decline explains the present crisis.”

Marxist-Humanist Initiative (MHI) regards this debate as a very important and very welcome phenomenon. Indeed, we hope that it is just the first of a series of similar debates that will take place throughout the left. Fundamental rethinking about the causes of the crisis and the continuing recession conditions is much needed and long overdue.

Far too many left groups uncritically repeat statistics and analyses produced by liberals and by large union bureaucracies and think-tanks like the Economic Policy Institute that rely heavily on union funding. Not surprisingly, the frequent result of the left’s over-reliance on such sources is the claim that capitalism is in fine shape, thank you; the problem is simply that the fruits of its remarkable success are being distributed very unevenly.

This line of argument was always implausible. But now, with the global economic crisis in its seventh year, we think it has become downright fantastical. The global economy limps along year after year with no boom in sight.

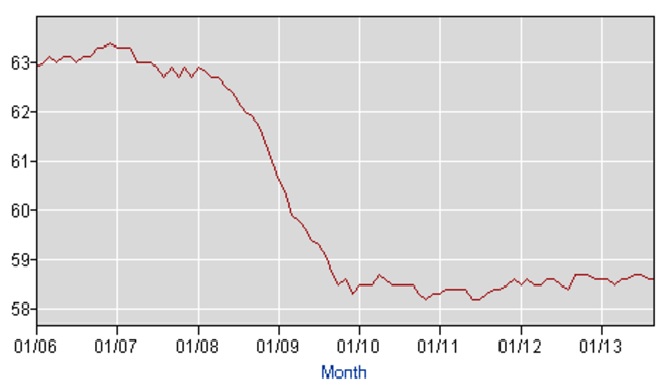

In the case of the U.S., this malaise can in no way be blamed on austerity policies. Since the start of the Great Recession, the federal government’s debt has shot up by an unprecedented 86%. The additional borrowing has fueled an extra $8 trillion worth of extra government spending and reduced taxes. Yet economic growth remains exceptionally weak and the percentage of people who have jobs hasn’t recovered at all (see graph).

Employed people as a percentage of U.S. adult population

* * *

Surprisingly, in its response to the dissidents in its organization, the leadership of the CWI has focused much of its counter-attack against the work of Andrew Kliman. Kliman is a Marxist-Humanist thinker and economist who has no affiliation with the CWI. However, his 2012 book, The Failure of Capitalist Production, is among the works that have informed the dissidents’ critique of the CWI’s economic analysis and policy proposals.

The leadership’s first major statement on the dispute, issued six weeks ago, is a 12,000-word document entitled “The Causes of Capitalist Crisis; Reply to Andrew Kliman.” It was written by Peter Taaffe, the general secretary of SP(E&W), and Lynn Walsh, its main economics writer. Much of the piece by Taaffe and Walsh is not about the economic crisis, but a scathing denunciation of the Marxist-Humanist philosophy and politics articulated by Kliman in his book and in With Sober Senses. Taaffe and Walsh argue that the internal opposition in their organization is guilty by association: “There is a very simple aphorism in judging individuals and political groupings: ‘Show me who your friends are and I’ll show you who you are.’” This comment is particularly ridiculous in this case, since the CWI dissidents have little in common with Marxist-Humanism except that both take Marx’s crisis theory seriously.

Shortly after the piece by Taaffe and Walsh was published, the dissidents responded with “What is the cause of the current capitalist crisis?: Critical Document on the CWI position,” which has been republished in “Marx Returns from the Grave,” a popular blog published by Bruce Wallace. Wallace, who belongs to the CWI’s Scottish section, is a leading member of the opposition.

Two weeks ago, Kliman published the first two parts of his own reply, entitled “Whole Lotta Mistakin’ Going On: A Reply to Taaffe, Walsh, and the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party (England and Wales).” In response to Taaffe and Walsh’s charge that he, and the CWI dissidents, adhere to a dogmatic theory, Kliman wrote,

Taaffe and Walsh feel entitled to reject any evidence that fails to confirm their preconceptions. There is a word for this: dogmatism. …

Ironically, Taaffe and Walsh accuse me of having a “dogmatic theory.” But this is just meaningless invective, because there’s no such thing as a dogmatic theory. Dogmatism has nothing to do with what one claims. It is a method of argument––the method of appealing to a premise that is not to be questioned, i.e., a dogma—whether the dogma one appeals to is the myth of creation or the myth that neoliberalism was a smashing economic success.

Another facet of the controversy concerns the SP(E&W)’s invitation to Kliman to speak at its “Socialism 2013” conference in London. As the dispute within the CWI deepened, this invitation was withdrawn. However, in an e-mail message to Kliman, the leadership of the SP(E&W) also asserted that “We have never avoided debates on important issues, and will not do so on this occasion.” It invited Kliman to two public debates, one in London and one in the U.S.

Kliman accepted the challenge and proposed that the U.S. debate be co-organized by MHI and Socialist Alternative, the CWI organization in the U.S. MHI has agreed to help organize the debate and has invited Socialist Alternative to be the co-sponsor. We are eagerly awaiting its reply.

Other organizations that have publicly taken notice of the dispute within the CWI include the Communist Party of Great Britain and Workers’ Liberty, another British radical organization.

Good evidence and good arguments seriously call into question the left-liberal myths that neo-liberalism triumphed over the working class and that the remedy for crisis is redistribution of income or wealth. We decry the near-total silence with which the evidence and arguments have been met. Kliman has been reviled for even questioning the left-liberal story. If the left is going to have any relevance to social movements in coming times, it better begin some real debates over these issues. The dispute that has erupted in the CWI is a good beginning.

Interesting article but I think this is quite a sweeping statement:

“Far too many left groups uncritically repeat statistics and analyses produced by liberals and by large union bureaucracies and think-tanks like the Economic Policy Institute that rely heavily on union funding. Not surprisingly, the frequent result of the left’s over-reliance on such sources is the claim that capitalism is in fine shape, thank you; the problem is simply that the fruits of its remarkable success are being distributed very unevenly.”

My own organisation would certainly not regard capitalism as being in “fine shape”. Capitalism is in chronic crisis and the CWI would definitely argue for this position. The question is why? The CWI currently argue that the crisis is due to underconsumption or a lack of money backed demand. This diagnosis is clearly false. if the diagnosis of the disease is false then the proposed cure will be wrong. That is the essence of the argument.

MHI wants to make clear that we fully support union struggles to improve workers’ lives. What we object to is unions’ common practice of telling workers that the company has plenty of money and is denying them their “fair share” (as if anything about capitalism is fair) only because the owners/bosses/capitalists are greedy and want to keep more profit for themselves. Of course they are greedy and try to pay the minimum they can get away with, but that “given” is not what determines whether they stay in business. Workers need to know that their getting a bigger slice of the pie depends not only on the militancy of their struggles, but also on whether the company’s rate of profit is sufficient to pay them more without it going bankrupt.

At every labor strike and rally to raise the state minimum wage that we attend in the U.S., the unions talk only about how big the pie is (the mass of profits), dazzling us with billion-dollar figures that make it seem intuitively as if the businesses in question are in fine shape and could be more generous to the workers if they were just not so greedy. But what determines whether a company remains profitable or goes under is not its mass of profits, but its rate of profit—how much it earns relative to how much it invests.

Union bureaucracies have a built-in motivation to mislead their members about what the union can do for them, so as to earn the members’ loyalty and thus keep their own jobs. This misleading need not be intentional; after all, most of the left and liberals present the same “greedy capitalists” theory in every class struggle, regardless of the state of the economy. When a union fails the membership, people often say its leaders were corrupted and intentionally sold them out. This may lead to a change in leadership, and the whole struggle starts over. Rarely does it lead to a discussion with the workers about Marx’s law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, and of the data showing a low rate of profit over the last several decades. The implications of those facts and theory are revolutionary; the union bureaucracies prefer to keep their role within capitalism.

In regards to “the underconsumptionist theory of Monthly Review,” MR’s editors are clear that they’re not underconsumptionists and that there’s no return to the Keynesian consensus:

“The root problem, as we see it, is not neoliberalism but capitalism itself. Neoliberalism (the economics of Hayek, Friedman, etc.) did not emerge as a dark conspiracy to drag capitalism from high growth rates and vibrancy; it became the orthodoxy when the system was in tatters in the 1970s, and when (bastard) Keynesianism was the establishment doctrine in disrepute. The choice before nations in that decade of crisis was to turn sharply to the left and go beyond existing monopoly capitalism to some variant of socialism, or turn hard right.

“What room there might have been at one time—and even then inscribed within the larger domination of center-over-periphery in the world economy—for a genuine Keynesianism, associated with social democracy of the Scandinavian variety is, in our view, now gone. The deepening stagnation of the mature, monopolistic economy, and the growth of financialization in an attempt to leverage up the system, represent the failure of the capital accumulation process at the system’s rotting center. The capitalist system as a whole is approaching its historic limits and needs to be transcended if the real needs of humanity (and the earth) are to be addressed.

“…This assessment does not reflect an ‘underconsumptionist’ argument on our part, as Palley suggests, but rather an overaccumulationist one. Indeed, we stress the fact that it is the accumulation, or savings-and-investment process, that is the problem. Simple promotion of higher wages or income redistribution will, no doubt, provide some welcome relief to a portion of society—to the very limited extent that this can be achieved within the system—but such measures will not solve the underlying problem. Much more revolutionary social changes are needed. Palley’s radical ‘structural Keynesian’ position, which lies in the tradition of orthodox Keynesianism and argues for something like a new New Deal as the ultimate solution, is one that we cannot accept in full, simply because it excludes the root problem: the accumulation of capital itself.”

Source: http://monthlyreview.org/2010/04/01/listen-keynesians-its-the-system-response-to-palley

MR editors, past and present, have taken some rather dubious political positions over the years (to put it mildly), but one ought to critique their ACTUAL views rather than make stuff up.

Jason,

You say that “MR’s editors are clear that they’re not underconsumptionists.” I don’t think so. They *allege* that they’re not underconsumptionists, but that doesn’t make it so.

Here’s what John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney wrote in MR in 2009:

“Capitalism, throughout its history, is characterized by an incessant drive to accumulate …. But this inevitably runs up against the relative deprivation of the underlying population …. Hence, the system is confronted with insufficient effective demand––with barriers to consumption leading eventually to barriers to investment.”

http://monthlyreview.org/2009/10/01/monopoly-finance-capital-and-the-paradox-of-accumulation

This is repeated in their recent book.

Here’s what Paul Marlor Sweezy, who developed the “overaccumulationist” theory that they endorse, and who founded MR, wrote in their magazine in 1995:

“If my analysis … is accepted, to what policy conclusions does it point? …

“The second indispensable change needed to make the private-enterprise economy work better is a redistribution of wealth and income toward greater equality. We live in a period in which an unprecedented and growing share of the society’s income accrues to corporations and wealthy rentiers, while the share of the underlying population stagnates or declines. This implies a permanent imbalance between society’s potential for adding to its stock of capital and its flagging consuming power. … Would the capitalist class as a whole, in extremis, be willing to give up half of what it has to save the other half? I have a feeling that the fate of the private-enterprise system may depend on the answer to this question.” (Sweezy, Paul M. 1995. “Economic Reminiscences”, Monthly Review 47:1 (May), pp. 1–11.)

MR’s current editors may wish to be less forthright about the political implications of their “overaccumulationist” (read: underconsumptionist) theory than Sweezy was, or perhaps they don’t understand its implications as well as Sweezy did. But what he identified as the implications are indeed the implications. If the barriers faced by capitalism are “barriers to consumption leading eventually to barriers to investment,” it follows that “a redistribution of wealth and income toward greater equality” would eliminate the alleged “permanent imbalance between society’s potential for adding to its stock of capital and its flagging consuming power.”

Thus, the editorial doesn’t “make stuff up,” as you charge. It does “critique their ACTUAL views.” I hope you will withdraw your charge.

I would be more inclined to withdraw my charge if your response more directly interrogated the piece that I actually quoted, rather than a different, previous, piece (which in any case still comes to anti-capitalist conclusions rather than redistribution-will-save-us-all ones), and — in particular — rather than an old piece by Sweezy, which I agree is very problematic but which Foster and McChesney obviously disagree with and are ignoring.

I have some hermeneutic questions. Please excuse me while I put my dunce cap on.

Isn’t it the case that the key to Marx’s theory of capitalist crisis is the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit (v. 3, Part 3, chs. 13-15; LTFRP)?

Isn’t it the case that the general law of capitalist accumulation (v.1, ch.25, which begins with the ratio c/v), and therefore also the historical tendency of capitalist accumulation (ch. 32), “the mad chase after value” (ch. 4),are technically precised by the LTFRP?

Isn’t it the case that the rate of profit is determined by the underlying rate of surplus-value (s/v)?

Isn’t the rate of surplus-value the ratio of unpaid to paid labor-power expended or consumed in the process of capitalist production?

Isn’t this the definition of exploitation?

And isn’t it therefore also the case that the many systematic contradictions follow from the endemic and necessary exploitation of labor in order to increase the rate of surplus-value; and therefore also at the same time to increase the organic composition of capital, the former entailing a potentially infinite numerator (like a “high cardinal” in set theory), the latter entailing a denominator impossibly vanishing to zero? Two impossibilities?

The law of value operates in the social relation that prevails at the point of production. This social relation is governed by socially necessary labor time (SNLT). The accumulation of capital depends on the perpetual reduction of SNLT, yet without variable capital (v), neither surplus-value nor profit can materialize.

Overaccumulation does arise in “the savings-and-investment process” (MR, cited above), but without stating what drives the saving-and-investment process, “overaccumulation” just means “underconsumption.”

Too much in the mass of capital has been accumulated to restore the rate of profit. In THE FAILURE OF CAPITALIST PRODUCTION, Kliman demonstrates that the rate of profit has never recovered from its decline in the mid-seventies. The alternatives within the capitalist organization of society are either massive liquidation of existing stocks and values or debt-financed “recovery,” which I believe everyone agrees is impossible to sustain in the longer cycle.

The underlying indirect cause of the Great Recession was the operation of the LTFRP.

Just as an interpretive matter, for the satisfaction of a monastic hermeneut,is this interpretation just too sloppy?

I recommend that everybody watch Kliman speaking in Slovenia (available on the MHI website). It’s really good. It includes a brilliant exposition of an overhead diagram explaining the difference between the indirectly social labor of capitalist production and the directly social labor Marx projected in CRITIQUE OF THE GOTHA PROGRAM for the lower phase of communism.

Tom

I need to correct an elementary mistake I made in what I wrote yesterday. I wrote that surplus-value is the ratio of unpaid to paid “labor-power expended.” Of course, this should have been stated as the ratio of unpaid to paid labor-time. Labor-power, the commodity, can be purchased at its value, below its value, or above its value. For purposes of his demonstration in ch. 7 of v. 1, Marx assumes that this commodity has been purchased at its value. This assumption is warranted by what we can think of as a best-case scenario in the logic of fair or equal exchange. The demonstration shows how a surplus-value is produced under the condition of an equal exchange, according to which workers are paid what their labor-power is worth. The capitalist pockets three shillings by doubling the length of the working day from six to twelve hours.

The reason why I wanted to resurrect this debate from last December–responding directly to Jason S.’s appeal to a distinction between “underconsumptionist” and “overaccumulationist” explanations of capitalist crisis, in defense of the MR’s editorial line in 2010; a distinction without a difference–is that Socialist Alternative appears to be gaining traction in the U.S. with the election of Kshama Sawant to the Seattle City Council, spearheading the Council’s vote to increase the minimum wage to $15.00. There is now a local affiliate of Socialist Alternative in the burg where I live.

A local spokesperson recently claimed in a public talk that the capitalists as a class are decisively winning the class struggle because they are awash in profits. Conditions were not propitious to draw the distinction between the mass of profit (relative to GDP) and the rate of profit.

So it’s incumbent upon a monk to join the battle of ideas in a particular locale where a flailing left has no idea of what it’s up to. Distinctions between “free” and “fair” trade and enthusiasms for “equal exchange” coffee are the best they can muster.

Tom