by Gabriel Donnelly

Much will be written, and much should be written, on the recent victory of the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) in its union election at the Amazon JFK8 warehouse in Staten Island. It is both the most impressive and the most visible labor union victory in America in decades, and it was accomplished by a newly-formed independent union.

It goes without saying that an Amazon warehouse is a true house of horrors. The grotesqueries of working conditions range from the deaths of six workers forced to work through a tornado warning in Illinois, to lax pandemic safety measures resulting in COVID deaths, and even the case of a worker lying on the ground for twenty minutes after a heart attack before receiving treatment. The JFK8 warehouse doesn’t seem to be an exception to this situation. In fact, it might even be worse. For example, JFK8 has an injury rate three times higher than the national average.

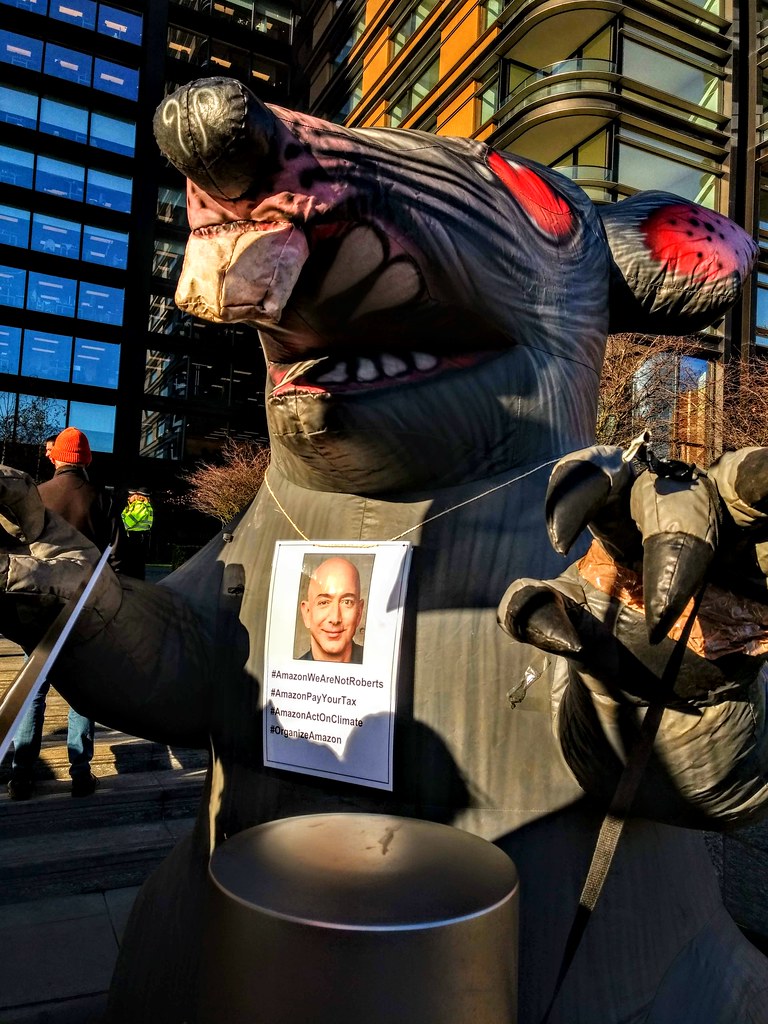

outside Amazon headquarters. Credit: War on Want.

The genesis of the union drive started after workers began protesting the company’s lax COVID safety measures in March, 2020. In response to these worker actions, Amazon fired protest organizer Chris Smalls, a figure who would go on to become the Amazon Labor Union president. The leaked remarks of an Amazon executive about Smalls were so flagrantly racist that the executive was forced to publicly apologize. These Amazon workers––who are facing antiblack racism, climate catastrophe, the pandemic, and workplace misery––are truly up against the worst that twenty-first century capitalism has to offer. And still they won.

This success in Staten Island stands in direct contrast to two failures in Bessemer, Alabama by the massive affiliated union, the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. The Bessemer drive was vocally supported by many prominent Democratic politicians, including Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders. In an interview with the Guardian, Smalls explained that his union’s rejection of the old unions was a conscious choice: “If established unions had been effective, they would have unionized Amazon already …. Established unions don’t really know Amazon and what it is to work at Amazon.”

Shortly after victory was declared on April 1st, 2022, Smalls was asked if he had a message for Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. He simply said, “Hell no … she doesn’t deserve this moment.” Perhaps this rejection of Democratic Party operatives was inspired by Amazon’s employment of Global Strategy Group (GSG), a Democratic consulting firm, to produce anti-union materials for the four Staten Island warehouses. GSG also monitored the social media accounts of ALU organizers.

the union’s victory at an April 1 press conference. Credit: Jodi Kantor.

This rejection of the old unions and even Democratic Party operatives should be recognized as a powerfully political and savvy act by these workers. In an article for Labor Notes, ALU organizer Justine Medina wrote at length about the roots of the union’s organizing approach:

We studied the history of how the first major unions were built. We learned from the Industrial Workers of the World, and even more from the building of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. We read William Z. Foster’s Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry (a must-read, seriously).

But here’s the basic thing: you have an actual worker-led project—a Black- and Brown-led, multi-racial, multi-national, multi-gender, multi-ability organizing team. You get some salts with some organizing experience, but make sure they’re prepared to put in the work and to follow the lead of workers who have been around the shop longer. You get the Communists involved, you get some socialists and anarcho-syndicalists, you bring together a broad progressive coalition. You bring in sympathetic comrades from other unions, in a supporting role.

Now, there’s much to criticize in all of this. The citing of an unreconstructed American Stalinist (William Z. Foster) in 2022 is far from exciting. In a sidebar to the article, Medina mentions her “organizing experience with the Young Communist League.” One must question her judgment. Beyond that, a rejection of the old, bloated, unresponsive union bureaucracies is laudable but can only go so far. There is no reason to believe that the ALU won’t fall into the same old traps.

We need only look at the recent reform victories in the Teamsters, like the bottom-up reshaping of the Chicago local or the (overstated) role of the rank-and-file Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) in the defeat of the corrupt and conservative Hoffa, Jr. slate in the 2021 general election. Already the O’Brien presidency has begun to shut the TDU out of the administration, a process which began even before he was formally inaugurated.

The point of this digression is to illustrate––with a particularly spectacular, mobbed-up example––the quagmire of modern American trade-unionism. It is a reformist treadmill that saps so many workers of their time and energy.

Still, these struggles can win short term, tangible victories. We mustn’t minimize how much these victories can matter. Decent union contracts can win higher pay, health care benefits, better hours, more confidence at work, and so on. These improvements can dramatically change the quality of life and overall happiness of the people at these worksites. ALU ran on securing safer work conditions, $30/hour pay, and longer break times. For workers doing grueling ten-hour shifts in unsafe conditions, and only making $39,000 a year, any one of those goals could be a godsend.

That being said, it’s shortsighted to pretend that such victories are stepping stones to abolishing capital. To convince ourselves otherwise would be to buy into a persistent fetishism on the left––the fetishism of movement for movement’s sake. The fetishism of activity and infrastructure construction (“build the party, build the party, build the party,” repeated as meaninglessly as phrases in a Latin mass) elides the desperate need for us to develop understanding, theory, and philosophy to address the underlying questions of our time.

The wing of Social Democracy most prevalent in our time––the Jacobin faction––and the outright tankies can both claim to believe in a new world, but we recognize that they only want the same world under a red flag. Note how Jacobin salivates over the infrastructure of Amazon and Wal-Mart. They don’t want to change the nature of work, but merely place themselves and their clique in charge of “rationally” managing it. Absurd texts like The People’s Republic of Wal-Mart highlight this salivation. Workers in Amazon deserve better than to keep working in Hell, and that is why we demand a change in the nature of work, not just how work is managed.

In their unsentimental, and deeply pragmatic, relationship to the old unions of this country, the workers of Amazon have already shown that they are moving towards these issues. To win against Amazon, they didn’t just consider the issues of the current moment, but reached into the past and read political texts and history. We can quibble about the content of their reading lists, and we should, but we must recognize what their action is moving toward. They are searching for political theory that explains their situation and provides them with the tools to develop solutions.

Much has been made of “the return of history.” Time magazine did a whole cover on the theme, as a refutation of Francis Fukuyama and the smug liberal idea that the collapse of the USSR settled all the major questions of politics. “The end of history” was never anything but a ridiculous position. However, its ascendancy among the liberal intelligentsia in the 1990s did point to a reality: that the ideology of capitalist hegemony had been greatly strengthened. The threat of Trumpism, the pandemic, climate crisis, police brutality, the war in Ukraine, and the recent explosion in unionization have all done far more than just reveal that “history isn’t over.” (Of course it isn’t.) What these existential crises truly reveal is how little can be competently managed by bourgeois governments and how much radical solutions are needed. The Amazon workers recognize this, consciously or not.

Take, for example, Amazon’s contentious relationship with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Shortly after firing Smalls, Amazon also fired Gerald Bryson, another ALU organizer and founding member. The NLRB ruled that this termination was unlawful and that Amazon must reinstate Bryson and give him back his old job. Despite this ruling, Amazon has used delaying tactics to avoid reinstating Bryson for two years. Furthermore, Amazon’s statement on the ALU’s victory seems to openly declare war on the NLRB: “We’re evaluating our options, including filing objections based on the inappropriate and undue influence by the NLRB that we and others (including the National Retail Federation and U.S. Chamber of Commerce) witnessed in this election.”

This is a direct attack on the dream of FDR, LBJ, Sanders, and Biden of a kindly federal government that can serve as a mediator in disputes between workers and capitalists, as long as the workers don’t go too far. It is difficult to imagine how an underfunded and already embattled NLRB will stand up to such an onslaught.

Bryson and the ALU have voiced appreciation that the NLRB issued the injunction against Amazon, but they may soon have to learn how to function without intervention from the NLRB. In the wave of Starbucks unionization currently sweeping the nation, the NLRB has gotten involved in the conflict, but on the other side. Starbucks Workers United (SBWU), which has weaponized social media in its campaigns, has started the hashtag #NoLaborRightsBoard to highlight how the NLRB is management-friendly, as well as understaffed, underfunded, and ineffective. So, we see a wave of union drives that has directly come into conflict with, or been failed by, the lingering institutions of Keynesianism. I believe that important lessons about the limits of liberalism can be learned from these interactions.

Workers at more than 150 Starbucks coffee shops have filed for union elections since the union won its first victory in Buffalo. Ten elections have been won so far. On a national level, nearly 70% of Starbucks workers are women. This drive is being led by young women, many of them queer. In fact, the youth of these workers has been highlighted by the clunky phrase “Generation U,” which combines Generation Z with U for “union.” In many respects, there could not be more differences between the Amazon warehouses and Starbucks coffee shops as workplaces, but what they both share is a very high rate of employee turnover. Unionization efforts at both Amazon and Starbucks seem to be about workers’ refusal to be treated as disposable by these very profitable corporations, and both are partly in response to the pandemic.

While the Amazon Labor Union is a completely new union, Starbucks Workers United merely presents itself as such. It claims to be “by partners, for partners,” since “partner” is the Starbucks euphemism for “worker.” In actuality, SBWU is an organ of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU)––an old, big, compromised union.

I myself am a Starbucks worker who is currently involved in a union drive. My store is organizing with the aid of another old, big, and compromised union, not with the SEIU. This has not diminished the feeling of solidarity with Starbucks workers in other stores, or the energy with which we fight. I think this indicates that Starbucks workers have a pragmatic and ruthless view of the unions to which they’ve turned; they view them as a tool. The nationwide union drive does not seem to be fueled by worker loyalty to any particular institution or labor leader.

Some years ago, a union organizer working on a campaign at a famously non-union retailer explained the importance of the campaign to me: “If we win at just one store, we will have shown that God can bleed and a wave of stores will follow us.” The Starbucks organizing drive shows this principle in action. The drive exploded only after the victory in Buffalo. The victory in Staten Island is another such case.

It is too early to say how the reaction to the ALU victory will manifest itself, but Amazon has already thrown millions of dollars into its failed effort to beat its workers. It will be extremely hard for the ALU to get Amazon to sit down at the bargaining table, let alone to secure a contract. There are innumerable ways that this moment can, and probably will, be spoiled by Amazon, or bureaucratization of the union, or both. But we must recognize that the Amazon workers made God bleed.

Be the first to comment