by Ángel Barroso

Editor’s Note: Last September, we published “Rallo’s Anti-Marx Critique of Marx and the TSSI: A Response,” by Andrew Kliman. On April 13, Juan Ramón Rallo replied to it (in Spanish) on his Substack blog, “Utilidad marginal.” The following day, Ángel Barroso responded to Rallo (also in Spanish) on his own Substack blog, “El Substack de Ángel.”

With Barroso’s permission (and at his suggestion), we are publishing the following translation of his response to Rallo. The text was translated by Francisco Palacios.

Andrew Kliman intends to publish his own response to Rallo, here in With Sober Senses, in the near future.

The Ángel Barroso vs Juan Ramón Rallo Debate on Marx, Kliman and TSSI (April 2025): A Solid Refutation of Rallo

The TSSI versus the Neoclassical Paradigm: A Chronicle of the Debate between Ángel Barroso and Juan Ramón Rallo

Introduction

The recent debate between Ángel Barroso and Juan Ramón Rallo on the validity of the Marxist labor theory of value and its solution through the Temporal Single-System Interpretation (TSSI) represents one of the most substantial intellectual exchanges in recent years in the field of Spanish-language political economy. Despite having taken place on digital platforms, mainly Substack and social media, the exchange far transcended the limits of the present current controversy to become a true clash of epistemological paradigms.

What began as a pointed discussion about a quote from Andrew Kliman quickly transformed into a profound confrontation between two opposing views of economics: on the one hand, the neoclassical-orthodox perspective, which interprets the economy as a self-regulating system in equilibrium; on the other, the Marxist, temporal, and systemic interpretation of the TSSI, which sees capitalism as a contradictory historical process in constant transformation.

In this article, I reconstruct the debate in detail, analyze its theoretical foundations, and highlight the methodological, political, and philosophical implications arising from this dispute. What follows is more than a chronicle: it is an exercise in conceptual clarification in defense of scientific Marxism.

The origin of the debate: A (decontextualized) quote from Kliman

It all began when Rallo quoted a passage from Andrew Kliman, a Marxist economist and one of the main exponents of the TSSI, in which Juan Ramón presented a quotation [from Kliman], taken out of context and completely distorting the original meaning of his critique. He portrays Kliman as if he were admitting that the Marxist transformation problem has no solution, when in fact he is saying something very different.

Rallo takes this quote as proof:

The “problem” he poses simply does not have an “economic solution.” Given profit-maximizing behavior, input substitution, and an economy that would be in a state of simple reproduction if commodities exchanged at their values, there are simply no prices that differ from values, whether temporally or simultaneously determined, that are compatible with that state of simple reproduction. It would be fatuous to require that we solve a “problem” that has no solution.

But what Kliman proposes here is not a renunciation of value theory or a recognition that the transformation problem is insoluble. What he does is criticize the way in which Rallo—and others from a neoclassical or simultaneist perspective—formulate the problem: demanding logically incompatible conditions (simple reproduction equilibrium, prices that deviate from values, profit maximization, etc.).

What Kliman says is that under this set of simultaneist assumptions, the problem has no coherent solution. And precisely for this reason, he defends a temporalist interpretation, in which values and prices are determined over time, and in which market price fluctuates around [gravita sobre] exchange-value, without the need for the two to coincide at the same instant.

The fundamental difference that Rallo overlooks—or chooses to ignore—is that Kliman does not confuse exchange-value with market price. He does not argue that the value of a commodity “tends to coincide” with its price, but rather that the market price fluctuates around [gravita sobre] its value in a temporal dynamic. This is consistent with Marxist theory, which recognizes market fluctuations without abandoning the centrality of labor time as the foundation of value.

So no, Kliman isn’t admitting that the transformation problem has no solution. What he is telling Juan Ramón is that the problem can’t be solved if simultaneist or neoclassical models formulate it, using categories from outside the Marxist approach. And using that quote to claim the opposite is, at the very least, an intellectual distortion.

Rallo naively claims that Kliman recognizes that the transformation problem has no solution, in order to assert that prices of production are simply averages of market prices. From this, he draws the conclusion that prices of production do not necessarily derive from values, which, in his view, deactivates the core of the labor theory of value.

My response was immediate and firm: that interpretation was erroneous, because it’s partial and because it’s decontextualized. Kliman never denies that prices of production are ultimately anchored in values. Rather, he reconstructs how values are transformed into prices of production through a temporal, historical, and non-simultaneous process. In other words, we are not dealing with an instantaneous algebraic formula, but rather with a logical sequence of transformations that unfold in the real time of capitalist production.

This is precisely the essence of the Temporal Single-System Interpretation: it does not divide values and prices as if they were separate systems, nor does it assume simultaneity between inputs and outputs. On the contrary, the TSSI shows how prices of production emerge in time from values, without violating the fundamental laws of capitalist reproduction. This temporal distinction is key, and it is what simultaneist readings—such as those of Bortkiewicz or Sraffa—fail to grasp.

Rallo insists: it must be demonstrated

Juan Ramón countered that, even if we accept that values may be the basis for prices of production, that does not imply that this is in fact the case. It must be demonstrated that prices of production are derived from values.

My point was that this demonstration has already been made. That’s precisely what the TSSI demonstrates, when the sequentiality of the production process is preserved. Not under Walrasian equilibrium conditions, but from Marx’s own logic. And demanding a demonstration in neoclassical terms is begging the question; you’re judging Marx by criteria he never shared.

The core of the conflict: the transformation problem

The so-called “transformation problem” is an old open wound in the history of Marxist economics. Raised by Karl Marx in the third volume of Capital, it refers to the apparent contradiction between the law of value (according to which commodities are exchanged in proportion to the socially necessary labor they contain) and the empirical reality of prices of production (which allow for a uniform rate of profit between sectors with different organic compositions of capital).

For decades, the most widely accepted solution was that of Bortkiewicz (1907), who corrected Marx by reinterpreting his model in terms of simultaneous equations. However, this correction involved radically modifying Marxist theory, discarding the direct relationship between value and price and giving rise to a “Sraffian” or “dualist” reading that many critics—rightly—considered a renunciation of Marx’s own dialectical method.

To confront this, the TSSI, formulated in the 1990s by Kliman and McGlone, proposes a radically different approach. It accepts Marx’s texts as written but interprets them temporally. This means that:

Input prices are determined at the time they are purchased, not in the future when the outputs are sold.

The rate of profit is not imposed simultaneously on the entire economy but rather emerges as a result of interactions between sectors over time.

The relationship between value and price is not broken, but rather dynamically transformed, preserving the law of value.

This interpretation not only mathematically solves the “transformation problem,” but also preserves the internal coherence of Marx’s system without resorting to ad hoc procedures.

Rallo didn’t refute anything, he just repeated objections that had already been overcome

An important part of Rallo’s intellectual defeat lies in his insistence on criticizing the TSSI with arguments that have already been answered decades ago. For example:

- the supposed impossibility of stable physical reproduction in the presence of changing prices

- the accusation that the TSSI assumes zero elasticity of substitution

- the idea that the coherence of TSSI depends on ignoring the rational behavior of capitalists

I addressed each of these points with technical precision, referring to concrete examples from Kliman’s work (such as Table 8.2 in Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”) and explaining how the TSSI not only contemplates [contempla], but incorporates, technological change, price adjustments, and capitalist competition as part of the process.

Rallo, on the other hand, offered no new rebuttal; nor did he respond to the empirical examples or dismantle the model internal logic of the model. His position remained a dogmatic reiteration of Bortkiewicz’s century-old prejudices.

Rallo didn’t understand the TSSI, and it shows

One of Rallo’s most blatant errors was his interpretation (or rather, misrepresentation) of the TSSI. He quoted Andrew Kliman out of context to insinuate that prices of production are disconnected from values, which supposedly undermines the core of the labor theory of value.

I solidly [con solvencia] refuted this accusation, showing that the TSSI does not eliminate the relationship between values and prices, but rather reconstructs it dynamically, without needing to assume that the prices of inputs and outputs are equal in all periods.

Furthermore, I used textual evidence from Kliman himself and empirical examples from the TSSI model to show how values determine prices over time. Rallo’s argument was not only weakened but also exposed as superficial and ill-informed.

“Dynamic equilibrium” as a neoclassical Trojan horse

In a methodological twist to the debate, Juan Ramón Rallo attempted to strike where it hurts most: the dynamic consistency of the model. According to his critique, the TSSI cannot guarantee dynamic equilibrium—understood as the economy’s ability to physically reproduce its inputs over time—because, by allowing changing prices between periods, the continuity of productive structures would be disrupted.

Rallo’s reasoning was as follows:

- If input prices change between periods,

- and capitalists, rational maximizers, adjust their production methods according to those prices,

- then the physical structure of the economy changes continuously,

- which makes simple reproduction or dynamic equilibrium impossible.

My answer was twofold: empirical and methodological.

From an empirical perspective, the TSSI does allow for physical reproduction, as can be seen in Table 8.2 of Kliman’s book, which shows that output can remain stable even with inconsistent prices. Capitalism does not require nominal stability to reproduce itself, but rather material viability.

From a methodological point of view, Rallo’s error was to assume that “dynamic equilibrium” is equivalent to “constant prices.” This is a requirement inherited from the Bortkiewiczian framework and neoclassical general equilibrium, not from Marx. The TSSI rejects this framework because it presupposes simultaneity, exogenous profit rates, and fixed structures—all conditions incompatible with the historical and contradictory logic of capital.

The accusation of contradiction (and why it’s not)

Juan Ramón tried to accuse me of contradicting myself, saying that on the one hand I claim that TSSI demonstrates physical reproduction, but on the other hand I say that it is incompatible with dynamic equilibrium.

The answer is simple: there is no contradiction. The TSSI accepts physical reproduction, but it doesn’t accept that it implies constant prices or simultaneous assumptions. It’s one thing to replenish the quantities needed for production: it’s quite another to require a constant price structure.

In fact, what I’m arguing for is just the opposite: physical reproduction can occur with changing prices, as long as physical proportions remain viable. And that’s entirely consistent with Marx and the TSSI.

This was one of the most tense moments of the debate, when Rallo tried to accuse me of falling into contradiction: on the one hand, I claimed that the TSSI allows physical reproduction, but on the other, I said that there is no “dynamic equilibrium.”

What Rallo didn’t understand (or pretended not to understand) is that physical reproduction doesn’t imply that prices must be constant or that the conditions of neoclassical simultaneous equilibrium must be met. I explained that reproduction can occur with changing prices as long as the physical proportions of inputs remain viable, which is perfectly consistent with the capitalist dynamics described by Marx.

The accusation of contradiction remained what it was: a logical trap that was dismantled in seconds.

The elasticity of substitution is a technical misunderstanding

In an attempt to strike a technical blow, Rallo accused the TSSI of implicitly assuming zero elasticity of substitution between inputs, that is, that capitalists do not change their production methods in response to price changes. He quoted Kliman as acknowledging that this assumption was unrealistic, suggesting that it invalidated the TSSI as a dynamic model.

Here I dismantled the criticism on three levels:

- Technical : TSSI does not assume zero elasticity. It simply models technological change decisions as part of intertemporal dynamics. That is, changes in technology can be incorporated, but they are neither instantaneous nor automatic.

- Empirical: In actual capitalism, processes of technical change are mediated by sunk costs, institutional rigidities, long-term investments, and labor resistance. Perfect factor mobility is a myth.

- Theoretical: Marx never assumed that capitalists responded perfectly to every price signal. His theory is based on tendencies, contradictions, and historical time, not on instantaneous Walrasian responses.

Beyond the equations this is a conflict of paradigms

Ultimately, the debate ceased to be about formulas and became what it truly was from the beginning: a confrontation between two radically different ways of conceiving the economy.

- Rallo’s paradigm is neoclassical: it seeks balance, models rational individual decisions, and trusts the harmony of the market.

- The TSSI approach is Marxist: it understands capitalism as a contradictory, chaotic system, driven by conflicting tendencies, and in which value is a social relation, not a technical property.

Therefore, although we sometimes argue using the same words, we do not speak the same language.

The Barroso-Rallo debate: the phantom of simple reproduction

On April 16, 2025, I had an extensive exchange with Juan Ramón Rallo in X following a critique he leveled at the Temporal Single-System Interpretation of Marx’s theory of value. The core of the discussion revolves around whether this interpretation can sustain the simple reproduction of capital without falling into logical inconsistencies or empirical contradictions. As is often the case in these debates, what appears to be a technical dispute actually contains a fundamental difference about how to understand Marx and the functioning of capitalism.

What initially seemed like an unequal confrontation—the celebrity economist versus the young 18-year-old researcher—ended up proving otherwise. Not only did I roll with the punches throughout the debate, but I outperformed him with clarity, demonstrating with explicit quotes from Marx how his premises were unequivocal and reasoned. Faced with this, Rallo opted for an evasive position, refusing to accept what Marx clearly and explicitly stated. His refusal was not intellectual, but tactical, a way of evading and redefining the argumentative defeat that, by then, was already inevitable.

The starting point: simple reproduction and physical proportions

It all began when Rallo questioned whether, within the framework of the TSSI, physical reproduction of the system is possible if relative prices change. His argument, in short, is that as soon as prices change, the material proportions between sectors can no longer be maintained, which makes unviable the in-kind replacement of means of production and consumption that is necessary to sustain the economic process.

I maintain that this is a misreading of Marx. In Chapter 20 of Book II of Capital, Marx clearly states that all conditions of production remain constant. This is not an addition on my part or a free interpretation: it is a literal quotation. In that context, the physical proportions between sectors remain fixed. It is precisely under this assumption that Marx elaborates his schemas of reproduction in Chapter 21.

Rallo attempts to relativize this point by saying that this physical constancy only refers to the replacement of fixed capital. But this ignores the broader analysis Marx deploys, where he starts from a stationary system, without accumulation or technical variations, precisely to isolate and analyze how global social capital circulates and is replaced.

How does simple reproduction affect this context?

The TSSI, developed by authors such as Andrew Kliman, has as its central objective the restoration of the coherence of Marx’s theory of value. Unlike simultaneist interpretations, which calculate prices and values at the same moment, the TSSI introduces temporal sequence and uses historical prices in the valuation of constant capital. This allows, among other things, the resolution of the “transformation problem” without having to abandon the idea that value is determined by labor.

Within this framework, simple reproduction is perfectly viable as long as the material proportions of the system are maintained. The fact that relative prices change does not invalidate the possibility of reproducing the same inputs in kind, provided there are no technical changes or substitutions between factors. In other words, as long as stationary conditions are maintained, as Marx assumed, there is no contradiction.

Rallo and the logic of capital

Rallo objects that my model implies that capitalists behave “irrationally”: that they do not substitute inputs when they become more expensive, that they do not seek to maximize profits. But this is a misplaced criticism. I have never claimed that such behavior is characteristic of real capitalism in motion. What I am arguing is that, within the specific analytical framework of simple reproduction, which is an abstract, stationary model with deliberately limited assumptions—the TSSI does not fall into inconsistency nor does it contradict Marx.

What Rallo seems to miss is that Marx uses these schemes not to describe the real economy as it exists, but as an intermediate step in analyzing its internal logic. There is no anti-capitalist concession or methodological voluntarism here: there is a clear theoretical strategy, moving from the abstract to the concrete. And at that abstract level, the system can reproduce itself perfectly with variable prices, as long as the physical proportions are maintained.

Rallo did not read Marx correctly, and … pretends to refute him

In an attempt to refute Marx’s model of simple reproduction, Juan Ramón tried to accuse Marx of having asserted that the model does not depend on constant and unchanging conditions. However, I quickly corrected him. Marx states in Chapter 20 of Volume II of Capital that “all conditions of simple reproduction depend on constant conditions.” This analysis is the basis of Marx results and subsequent numerical schemes of simple reproduction.

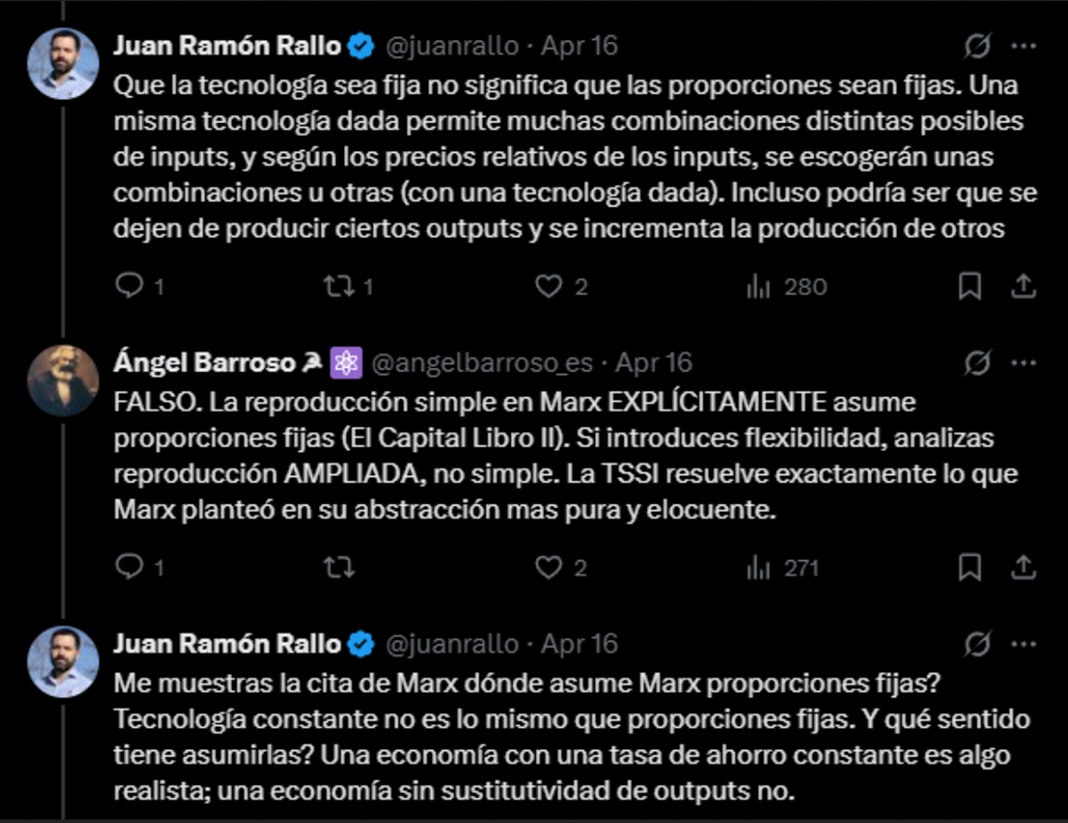

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

Just because technology is fixed, that doesn’t mean that proportions are fixed. A given technology allows for many different possible combinations of inputs, and depending on the relative prices of the inputs, some combinations will be chosen over others (with a given technology). It could even be that certain outputs are no longer produced and others are increased.

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

FALSE. Simple reproduction in Marx EXPLICITLY assumes fixed proportions (Capital, Book II). If you introduce flexibility, you analyze EXPANDED reproduction, not simple reproduction. TSSI resolves exactly what Marx proposed in his purest and most eloquent abstraction.

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

Can you show me the quote from Marx where he assumes fixed proportions? Constant technology is not the same as fixed proportions. And what’s the point of assuming them? An economy with a constant savings rate is realistic; an economy without output substitutability is not.

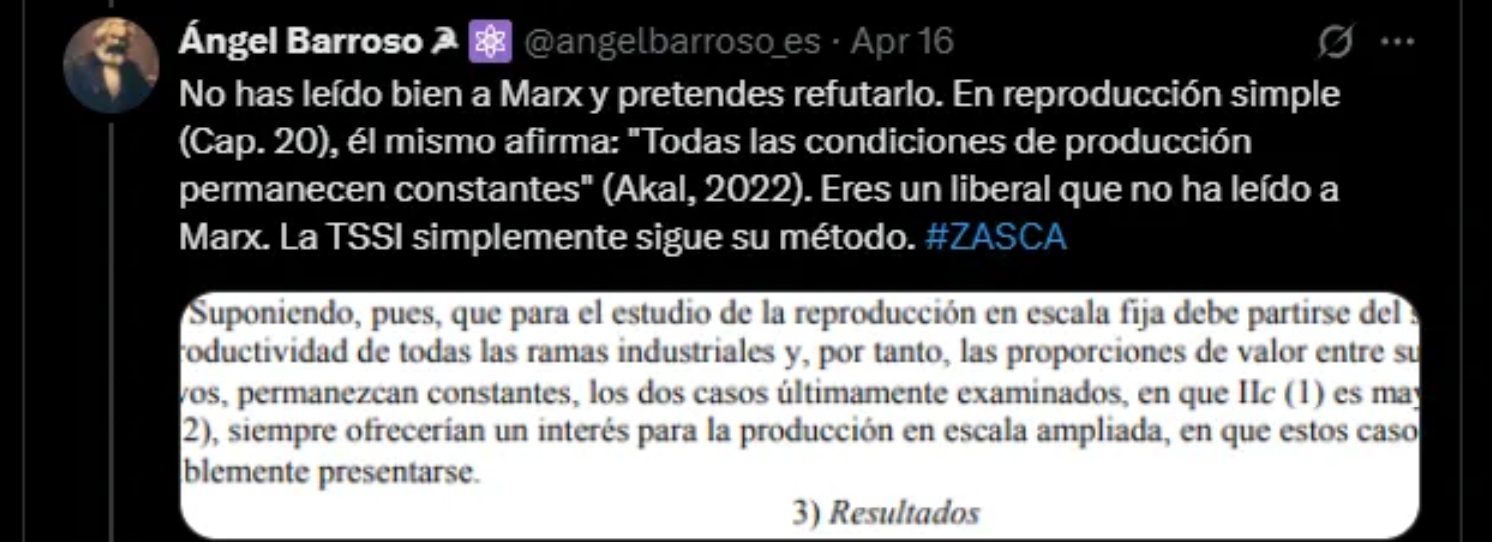

Angel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

You haven’t read Marx well and you intend to refute him. In Simple Reproduction (Chapter 20), he himself states: “All conditions of production remain constant” (Akal, 2022). You are a liberal who hasn’t read Marx. The TSSI simply follows his method. #BURN

Even if we assume, in considering reproduction on a constant scale, that the productivity of all branches of industry, and thus also the proportionate value ratios of their commodity products, remains constant, the two cases last mentioned, in which IIC (I) is greater or less than IIC (2), would still be of interest for production on an expanded scale, where they will inevitably arise. [Capital, vol. 2, chap. 20, section 11(b); p. 542 of Penguin ed.]

Page 423, first line of the second paragraph (Chapter 20: Simple Reproduction):

We will assume throughout this chapter that the scale of production does not change, that is, that all production conditions remain constant.–Karl Marx[1]

Rallo’s big mistake was entering Marx’s territory without knowing it. He applied neoclassical economics categories, such as factor substitution or rational choice based on relative prices, to a model that explicitly does not work with these variants.

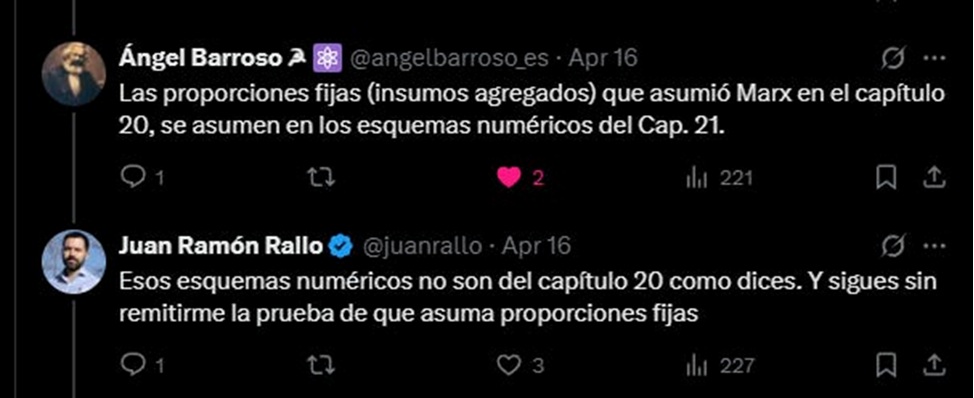

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

The fixed proportions (aggregate inputs) that Marx assumed in Chapter 20 are assumed in the numerical schemes of Chapter 21.

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

Those numerical schemes are not from Chapter 20 as you say. And you still haven’t provided me with proof that he assumes fixed proportions.

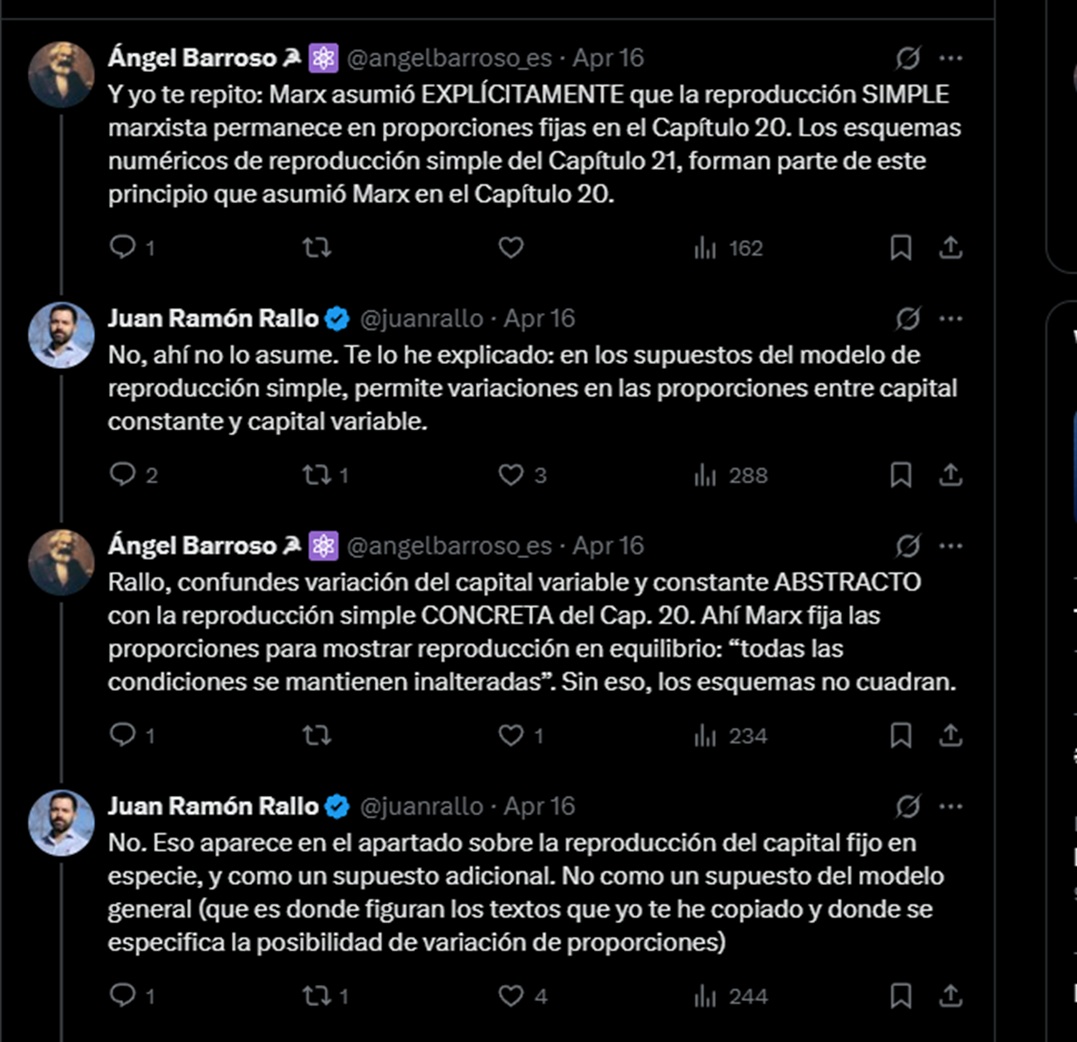

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

And I repeat: Marx EXPLICITLY assumed that Marxist SIMPLE reproduction remains in fixed proportions in Chapter 20. The numerical schemes of simple reproduction in Chapter 21 are part of this principle that Marx assumed in Chapter 20.

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

No, he doesn’t assume it there. I’ve explained it to you: under the assumptions of the simple reproduction model, it allows for variations in the proportions between constant and variable capital.

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

Rallo, you’re confusing variation in ABSTRACT variable and constant capital with the CONCRETE simple reproduction of Chapter 20. There, Marx establishes the proportions to show reproduction in equilibrium: “all conditions remain unchanged.” Without that, the schemes don’t add up.

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

No. That appears in the section on the reproduction of fixed capital in kind, and as an additional assumption. Not as an assumption of the general model (which is where the texts I copied for you appear and where the possibility of variation in proportions is specified).

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

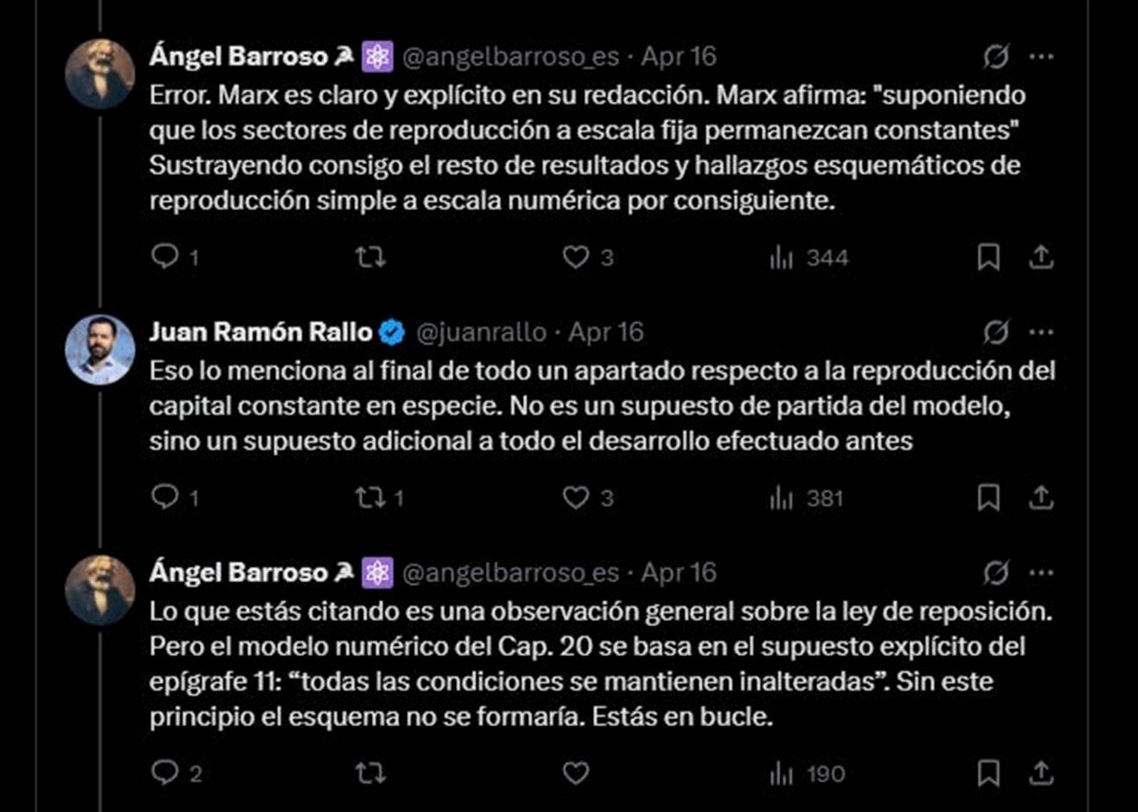

Error. Marx is clear and explicit in his writing. Marx states: “assuming that the sectors of reproduction on a fixed scale remain constant.” Consequently, he subtracts from the rest of the results and schematic findings of simple reproduction on a numerical scale.

Juan Ramón Rallo @juanrallo · Apr 16

He mentions this at the end of an entire section regarding the reproduction of constant capital in kind. It is not a starting assumption of the model, but rather an additional assumption to all the developments made previously.

Ángel Barroso ⚛️ @angelbarroso.es · Apr 16

What you are quoting is a general observation about the law of replacement. But the numerical model in Chapter 20 is based on the explicit assumption of section 11: “all conditions remain unchanged.” Without this principle, the schema could not be constructed [no se formaría]. You’re stuck in a loop.

At this point in the debate, Rallo didn’t respond further, and ended up losing in a loop [perdiendo en bucle]. After I had demonstrated with textual evidence in quotations from Marx that simple reproduction depended on constant and unaltered conditions, Rallo continued to deny reality by attributing words to Marx that he never articulated or defended. This is like criticizing a chess game by saying that you can’t score a goal. It’s not that the model is wrong; it’s that Rallo was playing a different game.

On the contrary, I not only demonstrated impressive textual mastery, but also a profound understanding of the internal logic of Marx’s system. With calmness and rigor, I dismantled Rallo’s objections one by one, making it clear that his interpretation was not only erroneous, but also misinformed.

This debate is not about minor details or accounting technicalities. What is at stake is whether Marx can be read coherently without needing to reinterpret him using the categories of neoclassical or aprioristic economics. The TSSI answers affirmatively, and does so with rigorous internal logic, without simultaneist traps or accounting manipulations.

Rallo, on the other hand, demands that the model incorporate from the outset capitalists’ reactions to prices, competition, and maximization. But that is asking Marx to start where he clearly does not. It’s like criticizing Newton’s gravitational model for not including general relativity; it’s a misunderstanding of scale and purpose.

Conclusion of the debate on X

The debate was valuable not only for its content, but for what it represented. It was a small but powerful reminder that Marxism is still alive, solid, and capable of responding with dignity [con altura]. And that when it is thoroughly understood, it is perfectly capable of defending itself against any criticism, even the most aggressive.

I didn’t just defend Marx. I defended the rigor, intellectual honesty, and critical thinking characteristic of the old school of thought.

And that, in these times, is a victory worth much more than simply “winning a debate.”

I know many will view this exchange as just another academic dispute. But those of us who study Marx seriously know that these questions matter. Because if Marx is incoherent, as his critics claim, then his critique of capitalism collapses. But if he isn’t—and I don’t think he is—then it’s worth continuing to read, defend, and discuss him, even in Twitter threads.

Why do I think I won the debate?

Not because of rhetoric. Not because of moral superiority. But because Rallo demanded that Marx demonstrate his coherence within a framework that Marx explicitly rejected. It’s like asking Darwin to prove evolution using the tenets of creationism. Nonsense.

The TSSI demonstrates that, when Marx’s temporal, sequential and dialectical logic is preserved, the labor theory of value is not only coherent, but capable of explaining:

a) Price formation without logical breaks

b) The distribution of surplus value between sectors

c) The downward trend of the rate of profit

d) Cyclical dynamics and crisis as an internal result of the system

There is no other interpretation that can achieve this without betraying the foundations of Marxism.

Rallo tried to assume that Marx said things he never said, while I pedagogically not only corrected him but also dialectically surpassed him.

A lesson beyond the debate

This debate also exposed a structural weakness of libertarian dogma: its inability to break out of the neoclassical framework. Rallo didn’t debate Marx; he debated a straw man that he invented using his own categories. And that is when he lost.

Not only did I defend Marx, I showed why it is still necessary to return to him. Because while orthodox economics revolves around the rationality of the consumer, Marxist thought continues to remind us that capitalism is not an preference-based equilibrium system [equilibrio de preferencias], but a historical form of social organization based on exploitation.

Final thought: Marxism is still alive (and kicking)

This debate has been a milestone, not because I say so, but because it has allowed us to clarify positions, update tools, and show that Marxism is not dead, nor is it a museum relic. It is alive, as long as it is read rigorously, without distortions, and with a genuine desire to understand its premises.

While some continue to wait for a perfectly balanced capitalism, we continue to analyze the real movement of history. And here, the TSSI is not only useful: it’s essential.

As I said at the end of the debate:

The greatness of the TSSI is not only that it solves the problem of transformation, but that it does so while preserving Marxist dialectics: showing capitalism for what it truly is—a system in perpetual motion, fraught with contradictions and destined to be overcome.

NOTE

[1] In the Penguin edition of Capital, vol. 2, pp. 470-471, the relevant passage is translated as “the conditions in which production takes place do not remain absolutely the same in different years (which is what is assumed here). The supposition is that a social capital of a given value supplies the same mass of commodity values and satisfies the same quantity of needs in both the current year and the previous year, even if the forms of the commodities may change in the reproduction process.”

Be the first to comment