by Ralph Keller

This is a brief digest of the results of the 2021 German federal election, which took place on 26 September. It is not a speculation on possible coalitions that will form the next government because there may be months of wrangling before a government emerges (although a coalition consisting of the Social Democrats, the Greens and the Liberal Party seems likely). Focussing instead on the official results alongside polling statistics reveals an understanding of why the AfD (Germany’s far right party) continues to be a strong force in all of Germany. Yet the results and the statistics do not explain why Die Linke (The Left Party) lost almost half of its votes. So, at present, one can only speculate regarding this point, with which this digest engages to some degree.

The Reichstag, Germany’s parliament building

The Reichstag, Germany’s parliament building

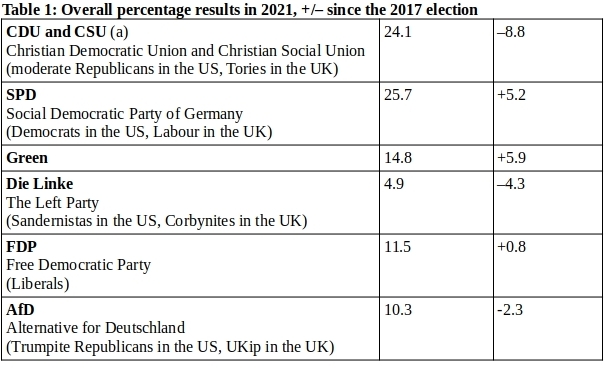

Germany’s federal elections are a hybrid affair that consists of direct mandates proportional representation. On the one hand this means that a party that wins at least 5% of the votes enters parliament as a faction, whose size is determined by the percentage of votes. A party may win additional seats if a candidate of that party wins in a constituency. On the other hand, a party that fails to win at least 5% of the votes may still be represented in parliament if a candidate wins in a constituency. The latter is the case for Die Linke, which won in three constituencies and thus won three seats, but failed to cross the 5% “hurdle”[1], as Table 1 indicates.

(a) CDU and CSU have a standing coalition, with the CDU being a party in all of Germany except in the state of Bavaria; the CSU is only a party of Bavaria.

Other noteworthy facts in Table 1 are that, first, the SPD will probably take the Chancellor’s office (equivalent to the Prime Minister in the UK and the President in the US) away from the CDU and the CSU, after 14 years of Angela Merkel’s reign. Second, the extreme right-wing AfD lost 2.3% compared with the 2017 election. Although this might be considered an encouraging result, it is not, because the loss is explained by the CDU and CSU having themselves adopted extreme AfD positions around immigration and refugee policy, as MHI reported previously. Nevertheless, CDU and CSU failed to capitalize on that capture because the more moderate centrist SPD won the elections (albeit by only a 1.6% margin) and therefore will probably hold the Chancellor’s office. It is expected, therefore, that we will see a more moderate stance than the current government’s dealing with refugees and immigration. Examples of this stance are that immigrants to be deported will no longer be taken out of a school class, while being at work, or during night hours.

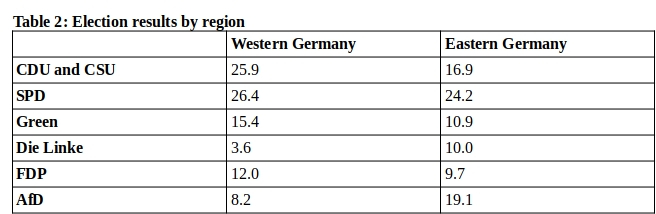

Third, digging further into the election results, Table 2 demonstrates that the AfD is no longer “an East German problem,” as bourgeois rhetoric has repeatedly claimed in the past. The same politicians have now switched rhetoric, saying that East Germans have “democratic deficits”. This guff not only aims at the AfD’s election results, but also at the result of Die Linke, because many bourgeois politicians consider Die Linke as holding extreme positions.

I do not buy into this rhetoric because, first, Die Linke, in contrast to the AfD, does not hold extreme positions intended to discriminate, intimidate, or spread “alternative facts” or outright lies. Second, Table 2 shows that the AfD would have crossed the 5% hurdle in Western Germany alone, which means that many Germans in the West also have “democratic deficits”.

However, it is true that the AfD is twice as strong in the East, which begs the question of why this is. One reason is that East Germans more readily subscribe to extreme right views, yet this reasoning provides only an incomplete explanation given the statistic in Table 3.

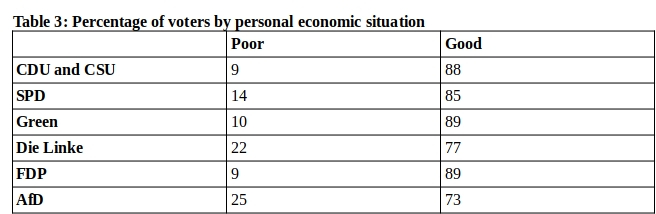

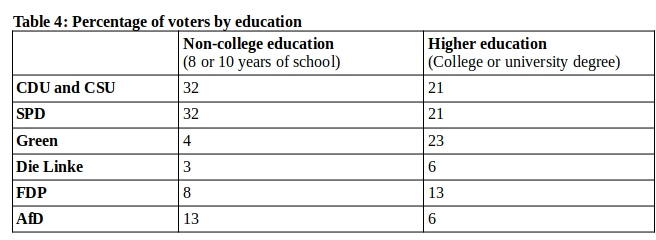

Table 3 reveals a correlation between voting behaviour and the economic situation as reported by individual voters. On the one hand, the SPD has a moderate percentage of voters who judge their economic situation as poor, of 14 / (14 + 85) *100 = 14.14%, while CDU and CSU, the Greens and the FDP have a low percentage of such voters. On the other hand, the AfD has the highest percentage, of 38.4%, followed by Die Linke, which has 28.6%. This begs the question why the latter two parties polarise their voters to such substantial degrees. Table 4 does not reveal an answer for Die Linke, but provides an indication for the AfD: it has the highest proportion of voters who have a non-college education, of 13 / (13 + 6) * 100 = 68.4%.

Thus, education seems to be a factor that contributes to understanding why many Germans vote for the AfD. In addition, Table 4 reveals another interesting fact, namely that the larger parties (those that won more than 20% of the votes overall) capture more voters that have a non-college education. Vice versa, the smaller democratic parties (those that won less than 20% of the votes excluding the AfD) have more voters that have a higher education. Although the AfD won less than 20% of the overall votes, it does not have a large percentage of voters with a higher education. To the contrary, the AfD strikingly stands out because has the largest percentage of voters with a non-college education. Interestingly, this is similar to the Trump voters in the US.

In conclusion, the statistics surrounding the 2021 general election indicate that Germany remains a divided country. This is because, as Table 2 has revealed, CDU and CSU, SPD, Green, and FDP have a higher percentage of votes in the West, while the AfD and Die Linke have higher percentages in the East. The statistics also reveal that the reason why the AfD remains strong, and much stronger the East, is a combination of non-college education, more readily subscribing to extreme right views, as well as the ongoing poorer economic situation compared with the West.

Regarding an explanation for the substantial losses of Die Linke, the situation is less clear, however. Even the party itself only engages in speculation and rhetoric at this point, but it seems clear that the party’s ongoing internal wrangling contributes to voters “defecting” to other parties or not voting at all. In addition, future research might reveal that some of the party’s voters defected in the wake of Die Linke’s tolerant stance on migration. However, only time will tell.

NOTE

[1] The 5% hurdle, or electoral threshold, was introduced after WWII to prevent a repeat of the 1918—1933 period during which seventeen splinter groups were present in parliament.

Be the first to comment