by Ralph Keller

This article provides an overview of the rise of the extreme Right in GermanyAfD (Alternative for Deutschland). In particular, the first part presents the various explanations proposed by politicians and the media as to why the party’s rise has been especially strong in East Germany, 30 years after unification. The discussion starts with East Germany because two states, Saxony and Brandenburg, held state elections on September 1, 2019. A third election took place on October 27, 2019, in the state of Thuringia, whose result has received international media attention. In addition, Germany as a whole faced the unique situation of being separated after World War II, and re-unified in 1990. As will be seen, this long period of separation continues to influence the unique situation in Germany today.

Other countries in the European Union (EU) have also experienced an alarming rise of extreme Right parties, albeit not to the same extent as Germany. Reasons that explain the rise include a fear of being left behind, resistance to social change, Russian meddling and the weaponization of social media.

Finally, the article attempts a critique of hitherto responses to the extreme right in the EU and concludes with reflections how to fight extreme Right ideas from a Marxist-Humanist perspective.

Election results in the East German states of Brandenburg and Saxony

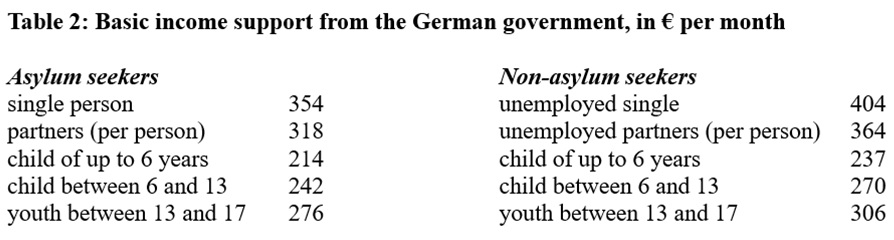

Table 1, below, shows the result of the state elections in Brandenburg and Saxony, both held on September 1, 2019. Previous elections were held in 2014. The discussion does not analyse the results in detail, for example, by discussing the constellations for possible new state governments. Instead, the discussion focusses on the gains of the AfD as the main force of Right extremism in Germany today.

Sources: https://www.wahlen.info/landtagswahl-brandenburg-2019/

https://www.wahlen.info/landtagswahl-sachsen-2019/

The gains of the AfD in both states are quite dramatic, with a similar pattern being present in other East German states.[1] Even more alarmingly, the most recent projections, according to the question “how would you vote if there was an election in your state next Sunday?”, show that the AfD would receive 20% of the votes in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, and 21% in Saxony-Anhalt; the discussion later in this article shows that the AfD achieved an actual result of 23.4% in Thuringia, in the election held on October 27, 2019.

Attempts to explain the rise of the AfD

The AfD’s election results and projections cannot be dismissed as a “protest movement” from a small minority. Instead, all established parties have now realised that the rise is quite dramatic. But this is not a recent phenomenon. The party has its origins in opposition to the 2015 Greek bailout, which the AfD and its supporters perceived to be helping Greeks at the expense of Germany.

A new stream of support has now taken over the original protest against the bailout. This new stream was triggered by the arrival of first refugees in 2015, when Chancellor Angela Merkel used her famous words “we will manage”. The extreme Right at the time, in the shape of Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident), then gained momentum as a protest movement on the back of mass migration into Germany. It is somewhat of a tragedy that Pegida was founded by Lutz Bachman, a resident of Dresden. This is because the city, like no other in Germany, represents war and destruction; and because the extreme Right spews its toxic propaganda by capturing the bombing of Dresden during World War II.

However, since Pegida is not a political party, it was instead the AfD that managed to capture the mood of many people who consider migrants to be a threat to the Western way of life. This mood also inspired the name “Alternative” for Deutschland, intended to change German politics, according to an extreme Right image, through parliamentary democracy. But what drives this mood, what fuels the hostility of parts of the population against migrants, and is this hostility the only reason why the AfD has grown far beyond a protest movement?

There have been many attempts to explain this, in the media and by Germany’s politicians. These attempts range from guff that teachers during the time of unification failed to educate their pupils politically, to more sophisticated explanations. One such attempted explanation singles out the consequences of quirky forms of state governance. Another emphasizes the AfD captures those parts of the population that feel left behind, in East as well as West Germany.

Although these attempts intend to explain the alarming rise of the AfD as a representative of Germany’s extreme right, they do not explain the existence of the extreme Right per se. This is an important point, but it extends beyond the scope of this article.

Alleged teacher failings

This “explanation” has become somewhat of a workhorse for Saxony’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party, which argues time and again that teachers failed to educate young people properly in democracy and dictatorship at or after the time of unification in 1990. Lately, Saxony’s former prime minister, Stanislaw Tillig, even argued that political education was deliberately removed from the school syllabus during the unification years, because this education had failed in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). A variation of this argument is that teachers of Russian were retrained to educate youngsters in Social Science. This must mean, according to the proponents of alleged teacher failings, that these teachers are not competent, or do not “put their heart into political education”. My reaction, when watching the TV documentary in which a politician presented this view, was: “you what?”.

Be that as it may, the “argument” that the rise of the AfD is rooted in the failings of teachers brushes under the carpet the fact that Saxony’s CDU has reduced the number of teachers during the course of many years, to cut down state expenses. And in any case, this “argument” is nothing but guff—especially after 30 years of German unity. It therefore seems to be an attempt to deflect from the failings of the CDU during its unchallenged reign between 1990 and 2019.

Quirky forms of state governance

Another explanation seeks to establish the failings of quirky forms of state governance over time, by the CDU in Saxony and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) in Brandenburg. An article in the Neues Deutschland newspaper on August 31, 2019, titled “Glanz, Gloria, AfD-Wähler. Was Sachsen und Brandenburg eint” (approximately, “Glamour, Gloria, AfD Voters. What unites Saxony and Brandenburg”), explores the governance in both states. The reasoning is that, in each state, one party has ruled supreme since the unification in 1990, building its success on a feeling of togetherness and “our way”.

Specifically, in the case of Brandenburg, the article attributed the success to the so-called “King Neighbour” feeling, referring to a particular sense of belonging. In Saxony’s case, the success allegedly arose from a “King Kurt” sentiment (in reference to Saxony’s former prime minister Kurt Biedenkopf) who ran the state like a monarchy. These feelings may seem strange to outsiders, and they are. The newspaper article described these feelings as “cultural ethnocentrism … that did not only create a feeling of being special”. With it also came what I consider nationalistic feelings within Germany, of an “us” in delineation from “the other” states.

Whereas the newspaper article captures the unique situation in only two East German states, quirky forms of state governance might have been at play in the three East German states that did not hold elections on September 1, 2019. It might therefore seem that the quirky forms discussed go some way in explaining the rise of the AfD as a representative of the extreme Right. However, during the 2009 elections in another East German state, Thuringia, the AfD only won 10.6% of the votes, while the Linke (Left) party won 28.2% to lead government. This means that, surely, there must be reasons other than quirky governance that explain why the AfD has had alarming successes in recent years.

Indeed, the results of the Thuringia election on October 27, 2019, support this objection. This is because the Linke has by now led the state government for only five years (this time winning 31%), which is too little time for quirky governance structures to develop. Yet the AfD still won 23.4% of the votes, with an alarming 12.8% point gain since the previous elections in 2014.

In other words, the evidence from Thuringia shows that quirky state governance is, at minimum, not the sole cause of the rise of the AfD throughout Germany. Although this evidence does not, by itself, rule out the possibility that quirky state governance is a partial cause, or the sole cause in some states, of the rise of the extreme Right, we do not think that quirky governance should be taken seriously as an explanation for that rise. It is not a genuine social-scientific hypothesis, but a talking point advanced during an election by partisan politicians, in an attempt to discredit a rival party.

The feeling of being left behind and mass migration into Germany

The article in Neues Deutschland did not discuss the economic situation that many East Germans find themselves in 30 years after unification. Helmut Kohl once promised “blooming landscapes”, but actually delivered the mass liquidation of factories and mass unemployment. Some politicians, mostly from the Linke, attribute the alarming rise or the AfD to economic distress, i.e., the depressed economic situation many East Germans find themselves in. So, exactly what sentiment does the economic situation create?

Expressed in simple terms, it is a feeling of being left behind, thus seeking a sense of belonging. This must be seen in the particular context that the life achievements of East Germans remain greatly under-valued 30 years after unification. For example, East Germans continue to receive lower pay for the same work. IG Metall, Germany’s dominant metal workers union, has been fighting unsuccessfully for a master contract in East Germany for 15 years. The union argues that the missing master contract is the reason why East Germans continue to receive lower pay while working 3 hours per week longer. In fact, a recent study by the Hans Böckler Foundation shows that East Germans are paid about 17% less than workers in West Germany. Pensions are also lower in East Germany because of long periods of unemployment. Expressed differently, East Germans have experienced, during the 30 years of unity, the opposite of the Marshall Plan, from which West Germany benefited after World War II.

The hypothesis of economic distress as a reason for the rise of the AfD may not be far-fetched. An article in Die Zeit Online reported on a study conducted by the DIW (Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, i.e., German Institute for Economic Research). Its findings include the fact that 50% of AfD voters are unsatisfied with their own economic situation. However, the feeling of being left behind does not pertain only to the 17% pay gap, or to the lower pensions. In addition, Franz et al. (2018) found that AfD voters in East Germany are particularly concentrated in rural areas with a largely elderly population. The authors suggest that the demographic decline of these areas is a driver of AfD support. This decline correlates a lack of job opportunities with the more socially and geographically mobile moving away. Those “stuck” in these areas thus experience, literally, the feeling of being “left behind”.

However, the evidence that 50% of AfD supporters are unsatisfied with their own economic situation establishes only that they disproportionately experience “economic anxiety” (a subjective feeling or set of attitudes). It does not establish that they disproportionately experience “economic distress” (poorer and/or deteriorating objective economic conditions). The distinction is important because things other than objective economic distress can cause people to be dissatisfied with their economic situation—for example, racist or xenophobic feelings that the economic supremacy of one’s own group is in jeopardy—and there is considerable evidence that this is the source of disproportionate “economic anxiety” among Trump supporters in the US. (MHI’s 2018 Perspectives contain a section that argues that support for Trump in the 2016 US presidential election was driven by specific attitudinal factors—racism, xenophobia, authoritarianism, etc.—rather than by objective economic distress.)

Furthermore, there seems to be no hard evidence concerning the driving forces behind support for the AfD. Even if AfD supporters do disproportionately experience objective economic distress, it would be wrong to automatically assume that their embrace of the AfD stems from the economic distress and not from racist, xenophobic, and nationalistic attitudes.

Particularly in light of the US evidence, we do not find it reasonable to conclude that AfD voters’ “economic anxiety” necessarily shows that they objectively suffer from disproportionate economic distress, much less that economic distress is the driving force behind the party’s rise. Due attention needs to be paid to the possible role of attitudinal factors such as racism, xenophobia, nationalism, and authoritarianism.

However, refugees and migrants arrive en masse in the midst of the unique situation in East Germany. They are perceived as a real threat, causing widespread fear that East Germans will descend even further economically. And the AfD preys on these fears with its toxic propaganda. It has become so common, so normal, that former Federal President Joachim Gauck called for a greater tolerance towards the extreme Right. And East Germans who would not vote for the AfD nevertheless repeat its arguments like a prayer wheel. One such argument is that “good people need to be afraid of migrants and the way they dress”, and that “migrants harm our children”.

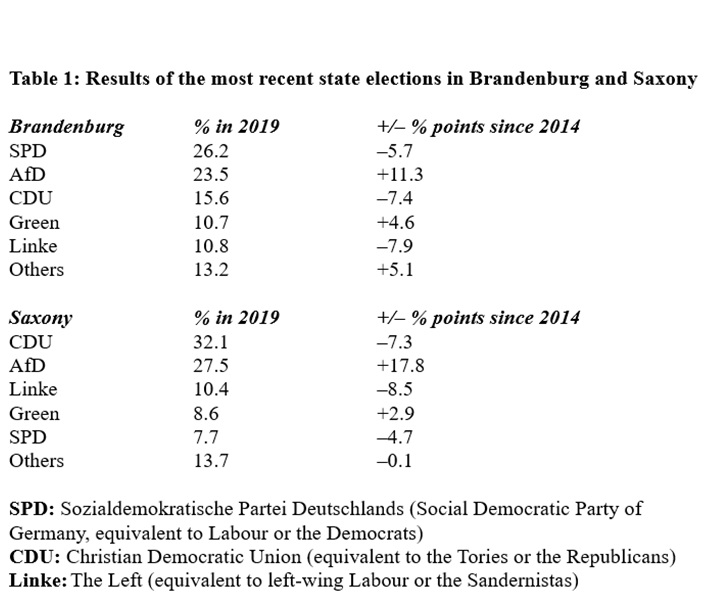

Another argument, expressed loudly at a supermarket checkout, is that “this is our money” and “these are our jobs”. This was a reference to Angela Merkel’s “we will manage”, and the alleged fact that migrants receive more cash from the state than unemployed non-migrants. To evaluate this alleged fact, consider the figures, in Table 2 below, which come from the reputable German news channel, n-tv. The income support given to unemployed non-migrants is higher, across the board.

Given these publicly available figures, it seems incomprehensible why some people sound off, shouting that “asylum seekers / migrants receive more cash than us, so that they can buy branded clothes and expensive smartphones!”. Even without the actual figures, rational people would not believe this toxic guff—except perhaps if they are met with the response that “hold on, these figures must be fake news”. They are not.

However, with fear comes, if not outright fascism, then at least a large dose of resentment and aversion to migrants. Following the AfD sheepishly may therefore be explained as an attempt of many people to gain recognition, and to fill the void that the neoliberal economic policies since 1990 have created. In addition, putting one’s faith in the AfD reflects a belief that strongmen will sort out the issues and take care of ordinary people. This comes with the unfortunate situation that the CDU during its unchallenged reign in Saxony since 1990 has constantly trivialized the rise of the extreme Right. It has therefore become “ok” to hold extreme Right views. This normalization contributed to the degree of normalization we witness today and that the AfD enjoys.

Extreme Right ideas as a phenomenon in all of Germany

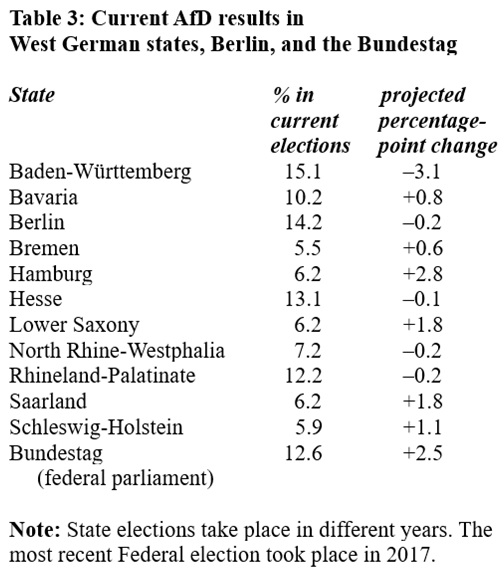

In my view, the unique economic situation in East Germany, paired with mass migration and ongoing trivializing of the rise of the extreme Right by the conservative CDU, explains the extent of the rise of the extreme Right in East Germany. However, the extreme Right has been rising in West Germany as well. For example, “birthday parties” of “you know who” (Hitler) take place every year. And CDU politician Walter Lübcke, in West Germany’s city of Kassel, was stabbed to death by a member of the extreme Right. The extent of the extreme Right’s influence in West Germany receives strong statistical support from the most recent projections. Table 3, which shows AfD percentages only, reveals the party’s presence in all West German states and Berlin, as well as in the Bundestag (federal parliament).

Source: Wahlen, Wahlrecht und Wahlsysteme

In West German states, the AfD is currently the strongest in Baden-Württemberg. But the party’s support there is still less than in the East German state in which it has the least support, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, where its share of the popular vote was 21% in the most recent state election. Although the AfD is not as strong in West Germany as it is East Germany, it is represented in all state parliaments as well as in the Bundestag. In addition, the “projected” column in Table 3 indicates that the current strength of the party in West Germany will likely persist in the next elections. This clearly shows that one can no longer dismiss the rise of the extreme Right as merely an East German phenomenon, although many politicians and the media have attempted to do so for years.

Other attempts to explain the rise of the AfD as the main representative of Germany’s extreme Right have now honed in on arguments presented, for example, by Cornelia Koppetsch. She argues that the rise of the AfD may be explained by reasons found within all social milieus. Specifically, Koppetsch argues that resistance to changing social values,[3] personality factors, and/or strong sentiments about social order would explain the rise of the AfD. Her position receives support from the scientific community. For example, Martin (2019) and Hansen & Olsen (2019) found that disaffection among AfD voters with the governing CDU, and hostility towards refugees, were driving forces for the rise of the AfD. Arzheimer & Berning (2019) also argued that there was a shift toward the AfD in 2015, as the “refugee crisis” unfolded.

Russian meddling and weaponization of social media

Finally, the rise of the AfD might possibly be explained, at least in part, as resulting from meddling by Russian’s government and the weaponization of social media. If valid, these explanations pertain to all of Germany.

A Spiegel Online report, referring to leaked documents and emails, reveals connections of AfD parliamentarian Markus Frohnmaier with Moscow. Reuters Online reveals that the AfD’s former front woman, Frauke Petry, also maintains close ties with Russia. This is significant because, as Spiegel Online argues, AfD politicians are largely foreign-policy novices and are thus easily manipulated by foreign powers, and especially Moscow, in this particular context. In turn, AfD novices may see an opportunity to make their mark on the world with the help of Moscow.

An online source reports that Germany has a large Russian-German community, which is unhappy with Angela Merkel’s welcoming attitude to Syrian refugees, as well as with the CDU now embracing same-sex marriages. This is a situation that Moscow intends to exploit through the AfD, to create a Putin-friendly climate in Berlin. Channels like Russia Today Deutsch, and Sputnik radio station support these efforts, and Spiegel Online claims that Sputnik often broadcasts “alternative” news. Worryingly, The Washington Post claims that many “Germans don’t seem to care” while “Russia is cultivating Germany’s far Right”.

But Russian meddling through the AfD, the news media and the parliament is not all there is. In addition, a Spiegel Online report points towards the weaponization of social media. That is, social media channels are flooded with pro-Russian messages. This report receives support in a recent scientific article by Serrano et al. (2019), titled The rise of the AfD: A social media analysis. Drawing on verifiable evidence, the authors argue that the AfD has relied on social media channels as an “alternative media” (p. 215), which shows that there is deep distrust in the mainstream media among AfD supporters. Indeed, at AfD rallies, a favourite slogan is “Lügenpresse, Lügenpresse”, which means “lying press” in English. In this context, Serrano et al. (2019) present evidence that social media posts use a provocative tone (a rather diplomatic description, in my view) “whose purpose is to viralize topics and manipulate trends” (p. 216). Being a wacko has become normal. This is the weaponization of social media, which has become a driver for the rise of Germany’s extreme Right in the form of the AfD.

Encouragingly, however, scientific studies find that the Right does not dominate all of social media. For example, Arzheimer & Berning (2019) and Neudert et al. (2017) found that, although social media have been particularly important for AfD supporters, the number of mainstream-media stories shared on social media during the 2017 election campaign was four times as great as the number of “bot-generated” or “junk” news stories that were shared. This ratio is good news because it indicates a limit in terms of how far the weaponization of social media had advanced as of 2017.

References

Arzheimer, K; Berning, CC (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013—2017, in Electoral Studies, Vol.60, pp.1-10.

Franz, C; Fratzscher, M; Kritikos, AS (2018). German right-wing AfD finds more support in rural areas with ageing populations, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW) Berlin, Vol.8, pp.69-79.

Hansen, MA; Olsen, J (2019). Flesh of the Same Flesh: A Study of Voters for the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in the 2017 Federal Election, Vol.28, pp.1-19.

Martin, CW (2019). Electoral Participation and Right Wing Authoritarian Success—Evidence from the 2017 Federal Elections in Germany, in Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Vol.60, pp.245-271.

Neudert, L-M; Kollanyi, B; Howard, PN (2017). Junk News and Bots during the German Parliamentary Election: What are German Voters Sharing over Twitter?, in Comprop Data Demo, Sept., Vol.7, pp.1-6.

Notes

[1] East Germany consists of five states; West Germany consists of ten. Berlin counts as a state in its own right. This is the result of the 1945 Yalta Conference, during which Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin agreed on the reorganization of Germany following World War II.

[2] The channel draws a number of comparisons, but the discussion here only compares people living in flats. The table therefore excludes asylum seekers and refugees living in shared emergency accommodation (disused hangars, tents, sports gyms, etc.) because these people receive even less cash, and because there is no equivalent for non-asylum seekers.

[3] This psychological jargon describes resistance to change within society that arises from the influx of migrants. Concrete examples are the now-common sight of the burka, the disrespect for “our” women that some young migrants allegedly display, and false beliefs and perceptions about the “dangers” that migrants allegedly bring. The latter include an alleged threat to “our” religion, or dangerous guff like “they are all criminals anyway”.

“From the spirits that I called Sir, deliver me!”

CDU and FDP are currently finding truth in this line from Goethe’s The Sorcer’s Apprentice because the two parties have been getting way too cosy with the AfD. This meant that Die Linke, who won 31% of the votes in Thuringia’s state elections to become strongest party in state parliament, were denied the post of state Prime Minister. Why? Because the FDP and the CDU went to bed with the AfD to deny Die Linke’s candidate, Bodo Ramelow – by the majority of 1 vote. So for now we have FDP Thomas Kemmerich at the helm.

Going to bed with the AfD is a result of two main issues. One, as I discuss in the article above, it comes after years of trivializing the AfD (not just in Saxony), and years of trying to adopt the AfD’s extreme-right positions. So far, this was mainly a dangerous CDU “tactic” to keep their voters from “defecting” to the AfD.

But now, a second issue has been added to the mix: lust for power. In plain English, the CDU and the FDP rather govern with the AfD, rather than not govern at all. The AfD, in this situation, rise to new “heights”, as they hail themselves as “king maker”! This is a dangerous situation because it is, plain and simple, a threat to Western democracy. What’s next, become “stirrup holder” to the AfD, meaning helping it to take power? We don’t need fascists again at the helm—yes, Thuringia’s AfD boss Björn Höcke, may be called fascist following a court ruling.

Recognizing this threat, the FDP’s federal committee stepped in to force Kemmerich to step down. Now the situation is unclear as to who will be PM in Thuringia. Will there be a new attempt to elect one, or will there be re-elections? Projections now show that Die Linke would win 38%, which is encouraging because

The FDP, and especially the CDU, must now get their act together to deliver the people of Thuringia, as well as Germany. Or, as Goethe put it 300 years ago: “From the spirits that I called Sir, deliver me!”