by Enrique Saiz

The results from the elections held in Andalusia last December fell like a bucket of cold water on many Spaniards. Andalusia seemed to have turned to the right.

It is a historically neglected autonomous community (comunidad autonoma––the term for historical nationalities and regions that have certain devolved competences [delegated powers]) within Spain. It has acute problems of poverty and inequality, but also a proud tradition of working-class struggle.

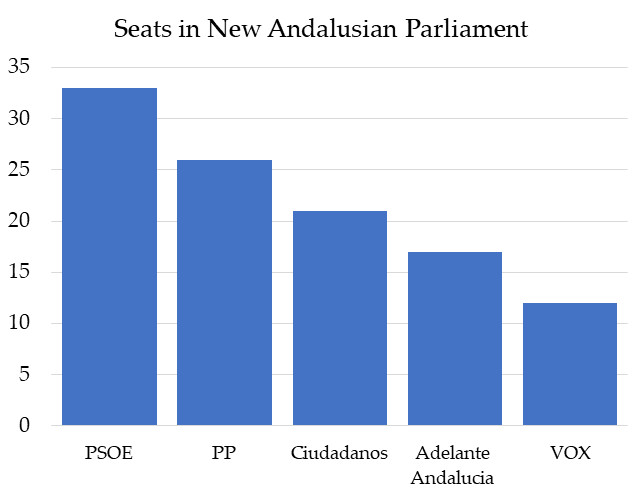

It’s not that the left held power in the autonomous community. Andalusia had firmly voted PSOE (the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) into power for most of its history but, as some readers know, the party has little to do with the historical party of the same name, and more to do with a refounding during the Spanish Transition that abandoned Marxism, led Spain into NATO, and deindustrialized the country in the 1980s. The modern PSOE is a social-liberal party with only hints of its once-leftist positions. Having ruled Andalusia for so long, corruption and cronyism scandals affected PSOE during these elections; the number of parliamentary deputies it won fell from 47 to 33.

Adelante Andalucia (Forward Andalucia)––the new-brand Podemos––and other smaller parties that competed in the election failed to capitalize on this vote hemorrhage. The number of parliamentary deputies they won rose by only two, from 15 to just 17. This was not enough to challenge the supremacy of the right: although the PP (People’s Party, the traditional conservative party in Spain) lost deputies, picking up 26, Ciudadanos––the new social-liberal party in Spain which claims to have no problem with issues such as homosexuality or feminism, but is enthusiastic about repression in Catalonia and stripping rights away from workers––more than doubled its performance, winning 21 deputies.

But the real surprise of the night was the incursion made by VOX, the Spanish far-right party that had previously held no political positions in any legislative body in Spain. They picked up 12 deputies. This had two consequences. First, they were now in position to act as kingmakers in Andalusia, capable of supporting PP and Ciudadanos to oust PSOE from power and end its 36-year rule in the autonomous community. Second, a “true” far-right party had finally arrived in Spain. Many people watched their TVs in dismay that night, as VOX, which publicly decries “communism,” “gender ideology,” “separatism,” and “the illegal invasion of Spain by immigrants,” celebrated its results with a big grin.

It is important, however, to point out two things. First, while VOX might be the first far-right party to obtain representation in an autonomous community parliament in Spain, the far right was already here.

For some time, far-right voters had voted for the PP or even Ciudadanos. The PP had always managed to keep a careful balance between Christian Democrats, moral conservatives, libertarians and liberals, and far right-wingers. That balance started to shatter when the PP saw itself affected by several corruption scandals. Some of those voters fled to Ciudadanos, a party which, as noted above, supports ideas of market deregulation and fewer worker rights, all in the name of maintaining the European Union consensus and promoting “flexibility” in the economy. But other voters were left in the cold: inasmuch as Ciudadanos deliberately adopts an ambiguous position on certain issues––such as women’s rights and homosexuality––some voters felt that it didn’t speak to them. As both the PP and Ciudadanos ramped up their Spanish nationalism in response to the Catalan crisis, as a rallying flag in an effort to gather votes and smash “separatism,” the stage was set for an even more-unfiltered version of the chauvinistic repressive right-wing platform they were offering: VOX.

Second, although people on both the right and the left have been quick to defend the idea that VOX is speaking for those “left behind” during the anemic economic recovery taking place in Spain after the Great Recession, that idea doesn’t hold much water. An analysis of the net income of neighborhoods (which roughly correspond to electoral districts) shows that the higher the income, the higher was the share of the vote received by VOX, the PP, and Ciudadanos. (For example, VOX received 15% of the votes in El Limonar, a neighbourhood in Málaga.) Also, VOX in particular polled better in neighborhoods with fewer immigrants from outside the European Union. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily mean that higher-income people voted for VOX––it is possible that the votes it received in high-income neighborhoods came disproportionately from low-income residents of these neighborhoods. But it does suggest, at minimum, that things aren’t as simple as they look.

In all probability, the bane of Adelante Andalucia and PSOE was not the defection of working-class voters to the far right. It was abstention from the election. In 2015, Podemos received 590,011 votes, compared to the 584,040 that Adelante Andalucia received last December, when they thought they could capitalize on the discontent of many voters with the PSOE. The latter, in turn, went from 1,409,042 votes to 1,009,243. Since abstention was greater in poorer neighbourhoods, both Adelante Andalucia and PSOE may have partucularly hurt by it.

Very informative and relevant article. Enrique, could you explain the significance of winning parliamentary disputes?