by Andrew (“Dave”) Kliman

Note: I wrote this in 2010, but it is being published here, now, for the first time.

Numerous studies supposedly show that industry-level “values” and “prices” are strongly correlated. Yet the strong correlation is actually between the total value and total price of industries’ annual output, not values and prices per unit of output. It has thus been demonstrated that this “empirical evidence” merely reflects the fact that the total value and total price of output are both large in large industries and small in small industries. Thus, according to the accepted definition of spurious correlation, the value-price correlation is spurious, since it disappears once we control for variations in industry size (as measured by total industry cost).[1]

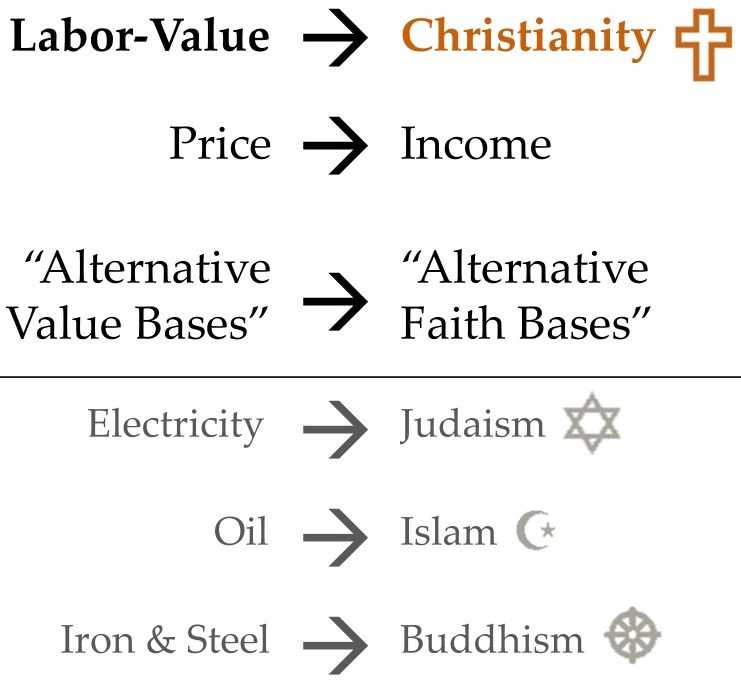

However, proponents of the correlation studies have doggedly refused to concede that their “empirical evidence” is bogus. This has the effect of perpetuating a scientistic and pseudo-scientific project that is hostile to theory in general and dismissive of Marx’s value theory in particular. Ignoring the definition of spurious correlation, they now claim that the correlations are “robust,” not spurious, because “labour values” are better than “alternative value bases” (e.g., electricity, oil, iron & steel) as predictors of “prices.”[2]

The present paper ridicules this dodge by means of a parody, which begins … now.

“Abstract

“This study investigates the empirical strength of the [Christianity theory of income]. It replicates tests from previous studies, using … data from [the 48 contiguous states of the United States, plus the District of Columbia, in 2001]. The results are broadly consistent [with those of previous studies]; [Christianity is] highly correlated with [statewide income]. The predictive power [of Christianity] is [then] compared to alternative [faith] bases.”[3] “[T]he results … provide substantial evidence for the empirical strength of the [Christianity theory of income]. [It] appears to be a very useful analytical tool for the study of the behavior of a typical capitalist economy.”[4]

1 “Introduction

“The [Christianity theory of income (CTI)] states that [income] tend[s] to be proportional to the [number of Christians] necessary to produce [it]. The scientific status of the theory depends on what it can say, theoretically and empirically, about reality. The [CTI] can generate interesting predictions regarding [income]-formation[ and] the decreasing [faith] content of [income]. …

“[Christianity] is an attractor to [income], or to put it in a different way, as Valle Baeza [1997] argues; [income] can be interpreted as a measure of [Christianity] and random [income-Christian] deviations as signals to which the … control system [responds with negative feedback].

“But the time and effort spent investigating what merits the [CTI] may have in real capitalist economies pales in significance to that spent on the so-called “transformation problem”––the problem of reconciling the [CTI with normal income data].”[5]

“[T]he transformation from [Christianity to income] was a live issue for Marx because he thought there really was a strong tendency for [per capita income] to be equalized, so that the simple [Christianity theory of income] would yield seriously counterfactual predictions. We will argue that Marx was wrong on this point.”[6]

“Against the background of the apparently interminable debate over the transformation problem at a purely theoretical level, one is led to ask why it has taken so long for economists to carry out relevant empirical investigations. … [E]mpirical tests of the theor[y] have had to wait until the last decade. The practice of political economy has in this area fallen far short of scientific standards. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that theorizing in the absence of empirical data leads only to arid speculation, which, in a domain like political economy, will be driven primarily by ideological pressures.”[7]

2 “Deviation between [income and Christianity]

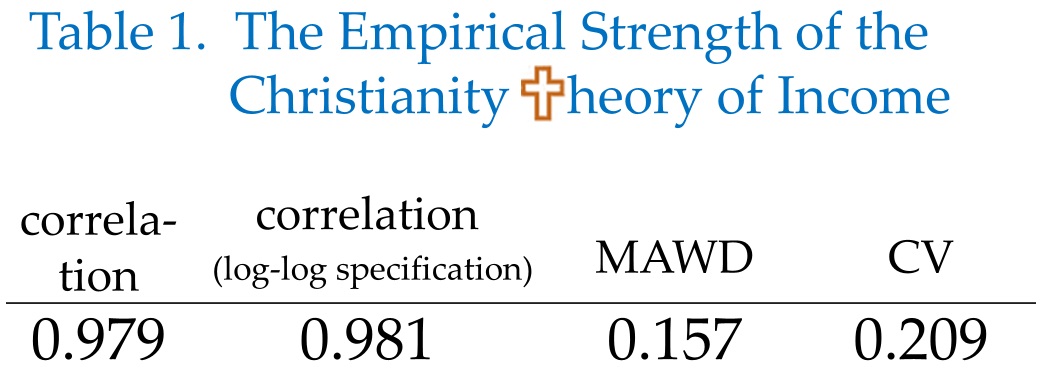

“One way to quantify the relation between [income and Christianity] is to measure the size of [states] in terms of [income and number of Christians] and compute how well the measures correlate with each other. Pearson’s correlation coefficient quantifies the linear co-variation between two sets of data. …

“Another measure used in the literature is the weighted average of relative deviations, MAWD .… It has … the drawback that it is affected by the normalization of the data but [it] allows a comparison with other studies. Following Shaikh [1998] [income is] rescaled so that the sum of [incomes] equals the sum of [Christians]. … A final measure is [the coefficient of variation, or the standard deviation of the income-Christian ratios relative to the mean income-Christian ratio].”[8]

Figures for the percentage of Christians in a state (and figures for the percentages of adherents of other faiths that will be analyzed below) come from Exhibit 15 of the 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris.pdf), which reports percentages for the 48 contiguous states of the United States and the District of Columbia. The Exhibit rounds percentages to the nearest whole percent. Whenever the nearest whole percent was 0, we set the log of the number of adherents of the faith in the state at zero. To obtain the total number of Christians (and adherents of other faiths), the percentages were multiplied by the states’ resident populations in July 2001, as reported in Table 12 of the 2010 Statistical Abstract of the United States (www.census.gov/compendia/statab/). To measure statewide income, we used personal income in current dollars of 2001, which is reported in Table 664 of the 2010 Statistical Abstract of the United States.

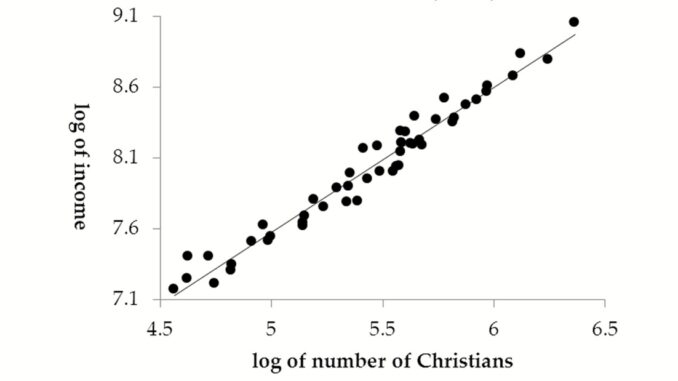

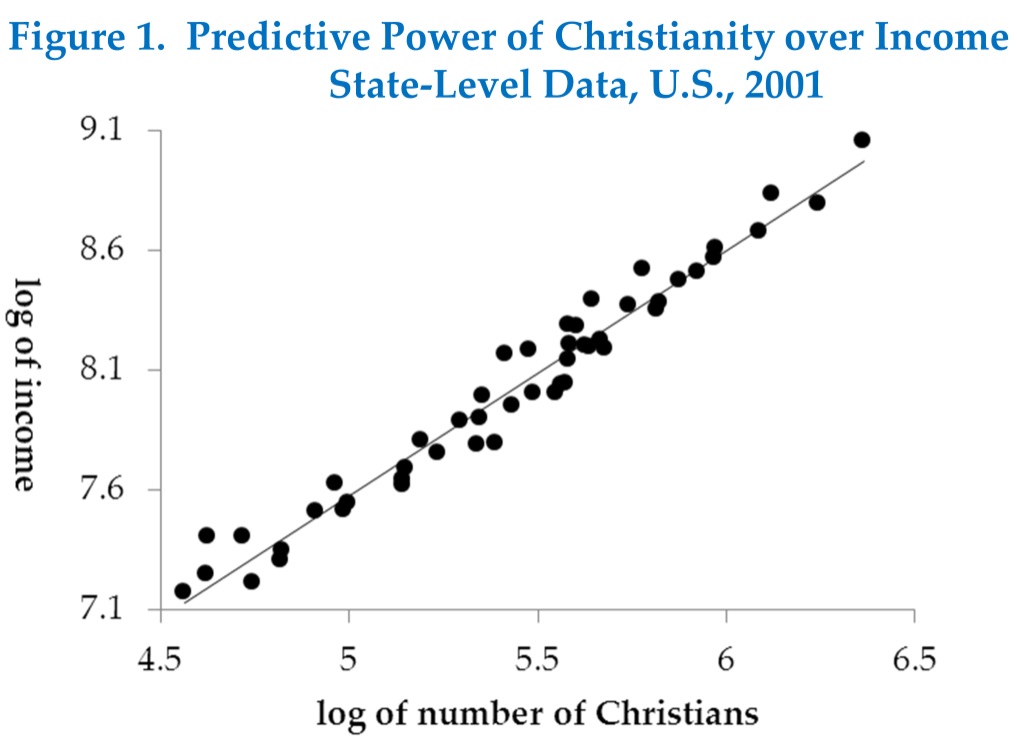

“The results are summarized in Table[ ] 1 [and Figure 1.]” [9]

These results, which are broadly consistent with those reported in other studies, show that “[Christianity is] the dominant determinant[ ] of [income]”[10] and that “variations in [income] are dominated by variations in [numbers of Christians].”[11] “Since replicable empirical regularities are rather rare in economics, the strong evidence these studies offer for a widespread coherence between [Christianity and income] is of indubitable scientific interest.”[12]

However, the CTI has critics, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science. “Instead of a positive research program … that analyzes the established economic order … and proposes concrete policies … [in their hands] the emphasis is shifted to textual interpretation of sacred scripts. [This is u]ltimately unproductive with the risk of being counter-productive.”[13]

These critics, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, claim to show that this empirical evidence merely reflects the fact that the total number of Christians and total income are large in large states and small in small states. For this reason, they contend that correlation results like those reported above are spurious.

The following definition of spurious correlation, which is fairly authoritative and representative, comes from Herbert Simon. “If we are suspicious that the observed correlation [between variables x and y] may derive from ‘spurious’ causes, we introduce a third variable, z, that, we conjecture, may account for this observed correlation. … [If] the correlation between x and y results from the joint causal effect of z on both of those variables, . . . this correlation is spurious.”[14] Thus, the critics argue, if we are suspicious that the observed correlation between the number of Christians in a state and the total income in a state may derive from ‘spurious’ causes, we introduce a third variable, the size of the states as measured by their populations, that, we conjecture, may account for this observed correlation. And if the correlation between the number of Christians in a state and the total income in a state results from the joint causal effect of statewide population on both of those variables, the correlation is spurious.

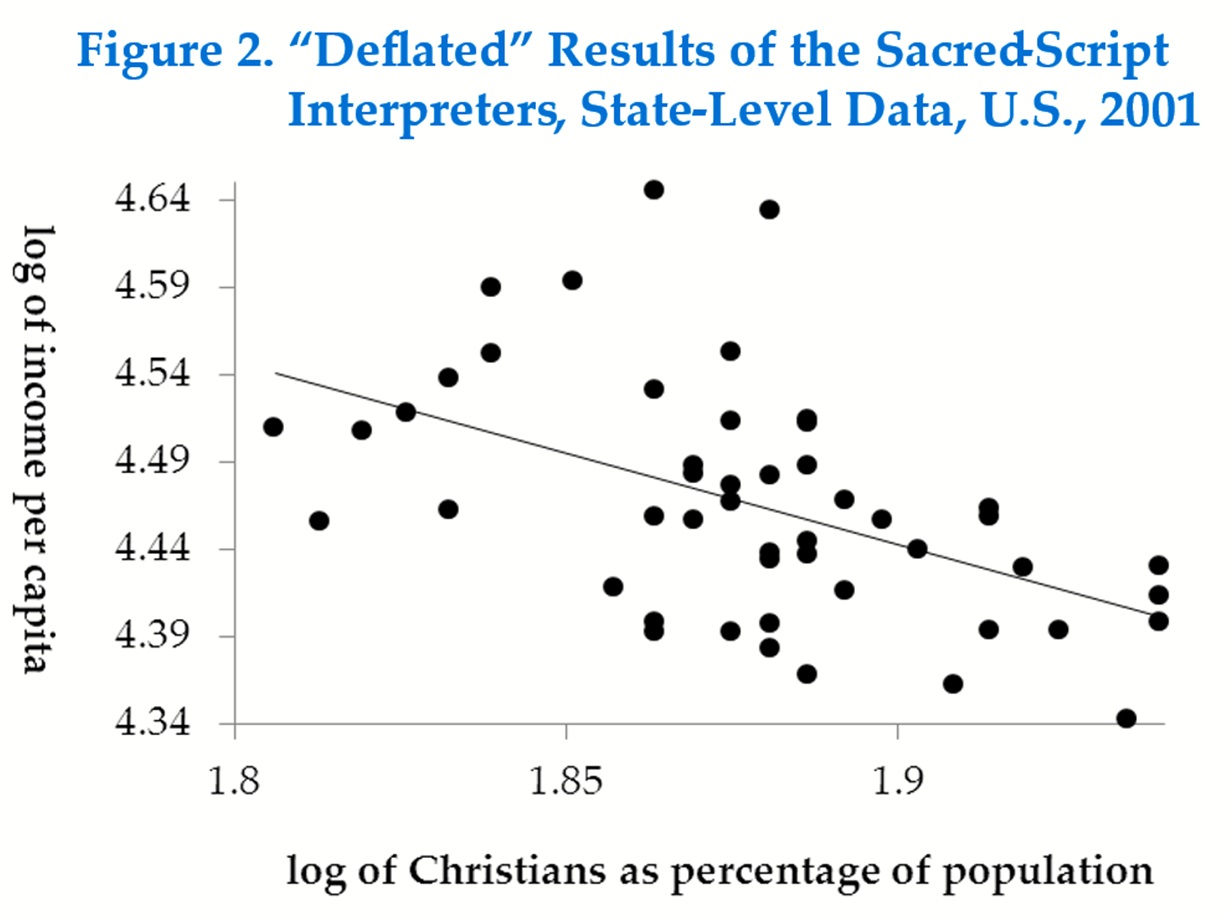

So the critics of the CTI, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, control for the influence of population on income by examining the correlation between per capita income and the percentage of the population that is Christian. For the data set being used here, this so-called “deflation” procedure destroys the Christian-income correlation. The correlation is now –0.477, or –0.498 when a double-log specification is employed (see Figure 2). The Christian-income correlation is also destroyed when this procedure is applied to other data sets.

On the basis of this supposed evidence, the critics, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, claim that the Christianity-income correlation is spurious, according to the accepted definition of spurious correlation, since it disappears once they control for variations in state size (as measured by total population).

But the correlations are not spurious; they are robust. When the critics, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, compute per capita income and the percentage of Christians, they divide total income and the total number of Christians by the number of people. But something is surely wrong with this procedure, since Christians are people. So “[t]here is no independent third factor that could plausibly induce a spurious correlation here.”[15] Thus the critics are “in effect , dividing through by the data.”[16] Their “statistical correction techniques involve dividing through by the signal [––people––] to leave the noise.”[17]

The basic objection of the critics, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, is that the correlation between Christianity and income is spurious because both of these variables are correlated with population, and it is actually the latter that is the dominant factor determining total statewide income. “But the objection has it backwards, for what [is population] if not [Christians]?”[18] In accordance with the Biblical injunction to be fruitful and multiply, that is exactly what Christians do. They produce (most of the) population. According to the data set analyzed in this paper, 75% of the U.S. population is Christian. So to say that population is the dominant factor determining income is merely a derivative way of saying that Christianity is the dominant factor determining income. “Surely, a [Christianity theory of income] cannot fall short to something as [superficial] as a [population] theory of [income].”[19]

“Hence it would be inappropriate to deflate [state income] by [the size of states as measured by population], as suggested in Kliman [2002], in order to address any spurious correlation arising from aggregation. This should rather be done by using less aggregated data or comparing results to alternative predictors as in section [3, below].”[20]

3 “Alternative [faith] bases: empirical evidence

“If the correlations between [Christianity] and [income] are essentially spurious (Kliman 2002), then one could produce equally good results using something other than [Christianity] as the ‘basis’ of [faith]. But this turns out to be false as shown [below].”[21]

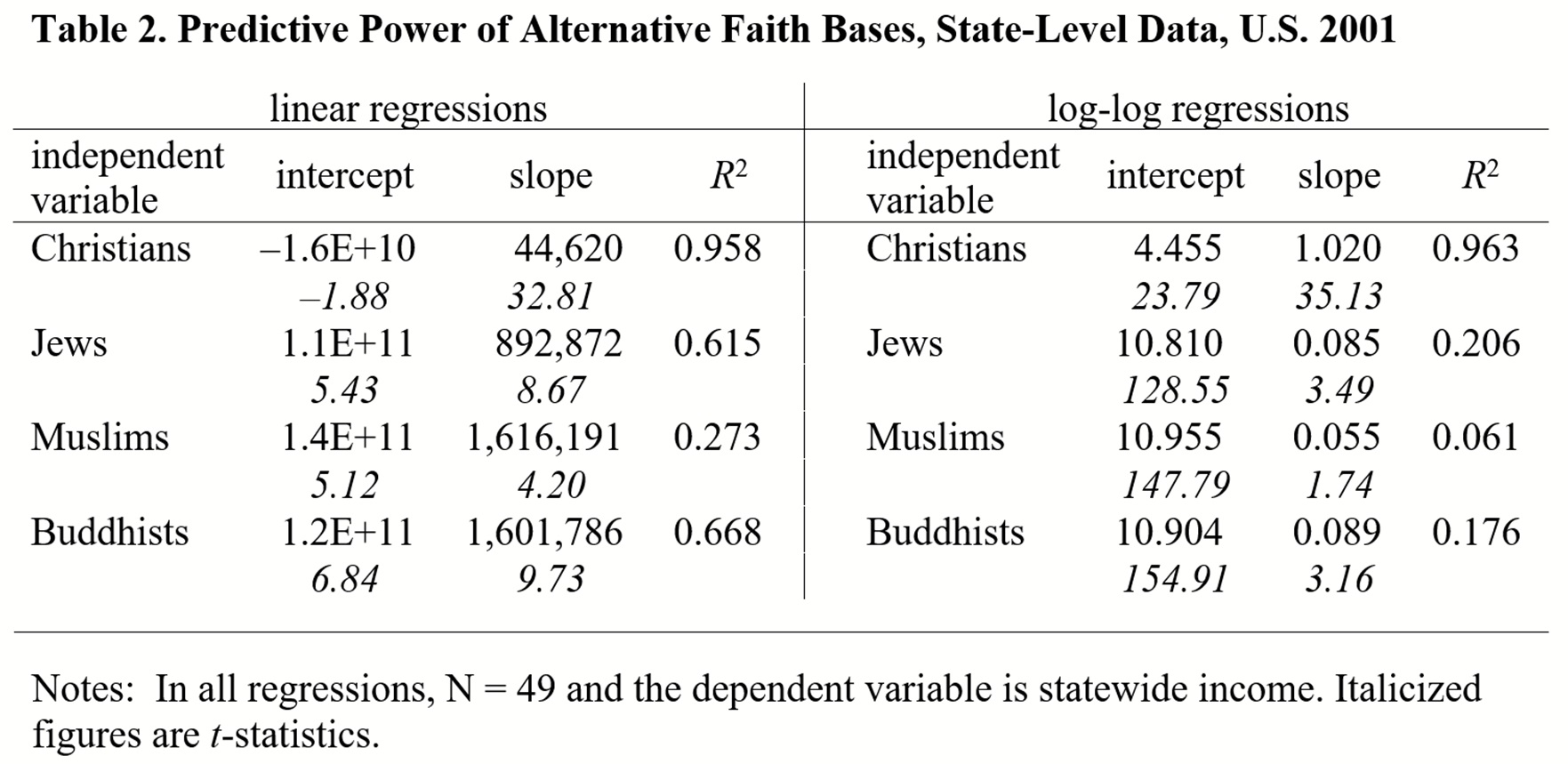

“It has long been suggested that, at least formally, a [‘Judaism’] or [‘Islam’] theory of [income] is equally plausible with the [Christianity] theory of [income] (Hodgson, 1982, p. 97). Namely, it is argued that [Christianity] has no special status as a ‘[faith] base’, and any other arbitrarily chosen [faith] could be used in place of [Christianity] when deriving [normal income] using either a system of simultaneous equations à la Bortkiewicz or applying the ‘iterative procedure’. Recently, Cockshott and Cottrell (1997) have indirectly addressed this issue by providing empirical evidence on the usefulness of the adjusted coefficient of determination in order to assess the closeness of [faith] and [income]. [… The faith] base … is calculated and then the explanatory power of [this faith] regarding [income] is compared with that of [Christianity]. No other [religion] tried as a [faith] base generates the extremely high R2s with [income] that [Christianity] do[es], and the authors conclude that these cannot be a ‘statistical artifact’.

“We repeated Cockshott and Cottrell’s exercise …. [W]e regressed [income] on … alternative [faith] bases. As Table [2] shows, … no other [religion] acting as a [faith] base comes close in covariance with [income] as the results obtained when [Christianity is used] as the substance of [faith] and the regulator of [income]. If the extremely high R2s … observed in the case of [Christianity] are produced by some statistical misspecification, this does not seem to hold true for other randomly chosen [faith] bases.”[22]

Two non-Christian faiths, Judaism and Buddhism, perform moderately well as predictors of income, though by no means nearly as well as Christianity, when total income is regressed on the total number of adherents of the faith. However, these results are not robust; they depend on the particular specification of the income-faith relationship. When a double-log specification is used, none of the non-Christian faiths performs well. However, Christianity retains its extremely strong predictive power over income. Thus “[t]he alternatives clearly fall short in the presence of [Christianity] which indicates that [it is the one true faith;] its empirical strength is not a statistical artefact.”[23]

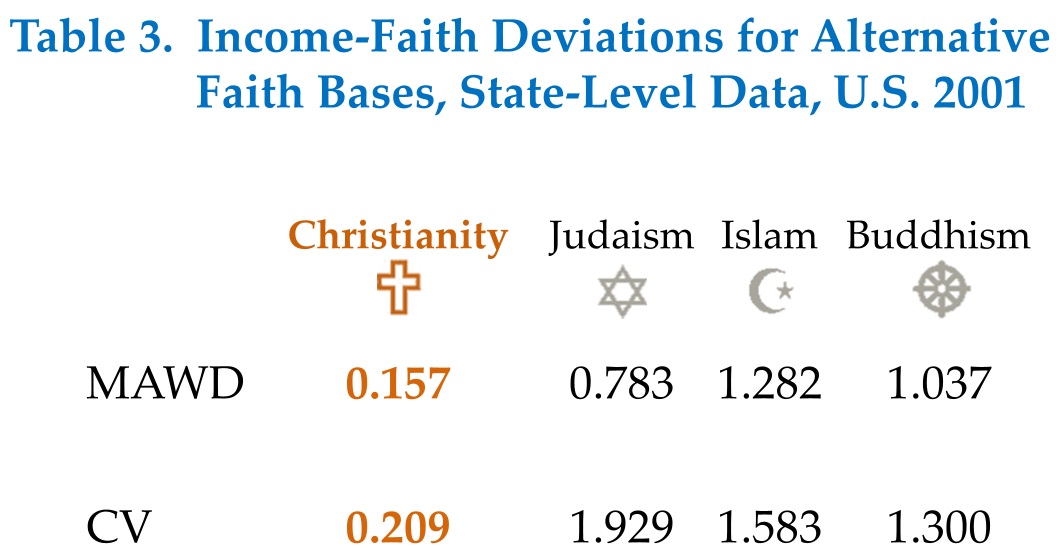

Measures of deviation provide further evidence on the superior predictive power of Christianity, as Table 3 indicates. Christianity outperforms the alternative faith bases to an overwhelming extent. When the faith base is a non-Christian faith, the income-faith deviations are between five and nine times as great as when Christianity serves as the faith base.

How might the critics of the CTI, who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science, respond to this very strong evidence that the income-Christian relationship is robust? They will probably appeal once again to a sacred script––in this case, the accepted definition of spurious correlation. They are likely to complain that this paper and other studies of alternative faith bases are simply ignoring this definition. Instead of trying to show that the correlation between income and Christianity is not spurious according to the accepted definition of the term, they will probably argue, these studies present the reader with numbers that have nothing to do with the accepted definition of spurious correlation and which are therefore irrelevant.

They will probably rigidly apply the accepted definition and therefore insist that, if the correlation between the number of Christians in different states and the states’ total income results from the joint causal effect of statewide population on both variables, the correlation is spurious. So they will probably insist that no contrary argument or evidence is relevant unless it shows that the correlation does not result from the joint causal effect of statewide population on income and the number of Christians.

It is of course the case that the results pertaining to alternative faith bases have nothing to do with the accepted definition of spurious correlation. These results are simply comparisons of different correlations with one another. They have nothing to do with whether these correlations are produced by the joint causal effect of population on income and the number of people adhering to a faith. But science is not a matter of quoting sacred scripts such as definitions. Nor is science of matter of rigidly adhering to definitions, as if it were invariably true that whenever a case conforms to a definition, the definition applies to that case.

Rather, as the great Scottish empiricist David Hume wrote, “reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”[24] Science is governed, and ought to be governed, not by sacred scripts such as definitions, but by the passions of those who are scientific.[25] Our passions tell us that the Christianity theory of income is correct, and our passions lead us to conclude that the evidence on the relative predictive power of alternative faith bases serves as empirical confirmation that it is correct. And despite what earlier authors wrote down in sacred scripts such as definitions, this really settles the matter. Science is Faith.

It cannot be too strongly emphasized that those who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science ought to be suppressed and censored. “[T]hey have taken valuable effort and printed pages in Marxist journals. Their publication in Sweden, for instance, has deepened the belief that Marxist economics is just a sterile academic obscurity.”[26] As Hume and Allin Cottrell have said about the work of such people, “Commit it then to the flames: For it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”[27] Freedom is Slavery; Ignorance is Strength.

References

Cockshott, Paul and Allin Cottrell. 1997. Labour Time Versus Alternative Value Bases: A research note, Cambridge Journal of Economics 21:4, 545–49.

_______. 1998. Does Marx Need to Transform? In Bellofiore, Riccardo (ed.), Marxian Economics. A reappraisal. Vol. 2: Essays on volume III of “Capital”: profit, prices and dynamics (London: Macmillan), 70–85.

_______. 2005a. Robust Correlations between Sectoral Prices and Labour Values: A comment, Cambridge Journal of Economics 29:2, 309–16.

_______. 2005b. What is at Stake in the Debate on Value[?]. Available at citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.60.2541&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Foley, Duncan K. 2000a. Recent Developments in the Labor Theory of Value, Review of Radical Political Economics 32:1, 1–39.

Hodgson, Geoff M. 1982. Capitalism, Value and Exploitation. Oxford: Martin Robertson.

Hume, David. 1999. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_______. 2000. A Treatise of Human Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kliman, Andrew. 2002. The Law of Lalue and Laws of Statistics: Sectoral values and prices in the US economy, 1977–97, Cambridge Journal of Economics 26:3, 299–311.

_______. 2005. Reply to Cockshott and Cottrell, Cambridge Journal of Economics 29:2, 317–323.

Ochoa, Edward M. 1984. Labor-Values and Prices of Production: An interindustry study of the United States economy, 1947–1972. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Economics, New School for Social Research, New York.

OPE-L. 1997. [OPE-L:4578] Re: The Practical Status of Butter Knives. Available at ricardo.ecn.wfu.edu/~cottrell/OPE/archive/9703/0312.html

Shaikh, Anwar M. 1984. The Transformation from Marx to Sraffa. In Mandel, Ernest and Alan Freeman (eds.), Ricardo, Marx and Sraffa: The Langston memorial volume (London: Verso), 43–84.

_______. 1998. The Empirical Strength of the Labour Theory of Value. In Bellofiore, Riccardo (ed.), Marxian Economics. A reappraisal. Vol. 2: Essays on volume III of “Capital”: profit, prices and dynamics (London: Macmillan), 225–51.

Simon, Herbert A. 1954. Spurious Correlation: A causal interpretation, Journal of the American Statistical Association 49 (267), 467–79.

Tsoulfidis, Lefteris, and Thanasis Maniatis. 2002. Value, Prices of Production and Market Prices: Some more evidence from the Greek economy, Cambridge Journal of Economics 26:3, 359–69.

Valle Baeza, Alejandro. 1997. Prices as a Means of Regulating and Measuring Labor Values, Research in Political Economy 16, 215-241.

Zachariah, Dave. 2006. Labour Value and Equalisation of Profit Rates: A multi-country study, Indian Development Review, vol. 4. Available at reality.gn.apc.org/econ/Zachariah_LabourValue.pdf

_______. 2010. [Comment #59 on “The Falling Rate of Profit page” of the Kapitalism 101 web site], kapitalism101.wordpress.com/the-falling-rate-of-profit/, posted on Feb. 17, 2010 at 5:47 am.

Notes

[1] See, e.g., Kliman 2002.

[2] Cockshott and Cottrell 2005b, Zachariah 2006.

[3] Zachariah 2006, p. 1, Abstract.

[4] Tsoulfidis and Maniatis 2002, p. 369.

[5] Zachariah 2006, p. 1.

[6] Cockshott and Cottrell 1998, pp. 70–71.

[7] Cockshott and Cottrell 1998, p. 84.

[8] Zachariah 2006, pp. 7–8.

[9] Zachariah 2006, p. 8.

[10] Ochoa 1984, p. 224.

[11] Shaikh 1984, p. 64.

[12] Foley 2000, p. 19.

[13] Zachariah 2010.

[14] Simon 1954, p. 468.

[15] Cockshott and Cottrell 2005a, p. 310.

[16] Cockshott and Cottrell 2005a, p. 315.

[17] Cockshott and Cottrell 2005a, abstract, p. 309.

[18] Zachariah 2006, p. 14.

[19] Zachariah 2006, p. 14.

[20] Zachariah 2006, p. 7 n6.

[21] Cockshott and Cottrell 2005b, p. 13.

[22] Tsoulfidis and Maniatis 2002, pp. 365–65.

[23] Zachariah 2006, p. 14.

[24] Hume 2000, p. 264.

[25] It certainly ought not to be governed by the passions of those who prefer interpreting sacred scripts to doing science!

[26] Zachariah 2010.

[27] Hume 1999, p. 211. Cottrell’s statement is reported in (OPE-L 1997); the rules of that list forbid me from indicating the author of the post.

Be the first to comment