by Theresa Henry

Part One: Evaluating the Significance of the Jina Uprising

The following is the first part of a two-part article, “Furthering the Idea of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement in Iran.” Entitled “Evaluating the Significance of the Jina Uprising,” this article will argue that the Jina Uprising has social and political implications not just for Iran, but the entire world. Begun on September 16, 2022, after the murder of young Kurdish woman Jina (Mahsa) Amini by the Islamic Republic’s so-called “morality police,” the Jina Uprising was a full year of mass demonstrations led by women and youth. “Woman, Life, Freedom” (henceforth WLF), originally a slogan associated with the revolutionary movement in Kurdistan, emerged as the animating idea of the uprising.

Quicky, WLF spread across the world. For example, the slogan gripped the hearts and minds of Muslim women in Turkey, India, and Afghanistan. Further, on November 12, 2022, people in 128 cities and 28 countries organized solidarity rallies. While attention was on Iran, the former Shah’s son, Reza Pahlavi, formed a coalition of liberal and right-wing forces to co-opt the movement. Progressive intellectuals around the world responded to the events in Iran, too. Perhaps most notably, Asef Bayat, a renowned Iranian scholar of revolutions, remarked that “political life in Iran has embarked on an uncharted and irreversible course.” Without a doubt, the Jina Uprising was an important historical moment in Iranian history.

Jina Amini. Credit: Womanlifefreedom.today

Section A of this article will discuss how the new generation of socialist and feminist revolutionaries who participated in the Jina Uprising understand its implications for Iran’s future, namely, that the revolutionary movement has not been defeated. Section B will critique a dominant tendency in the reception of the rebellion by the Marxist left—the tendency to simply pass judgements on social movements. Section C will discuss the global implications of the Jina uprising and WLF. I conclude part one of this article by showing that WLF, as articulated by the revolutionaries in Iran, offers an alternative vision to the rising forces of reaction in the world, but also those on the left, who refuse to confront these forces.

Yet, the vision of WLF is not complete. Already, during the Jina Uprising, counter-revolutionary tendencies within the left were identified by the revolutionaries in Iran. Thus, there is no guarantee that the current movement will lead to the truly free, human, and classless society envisioned by the freedom fighters. For this reason, it is necessary to figure out how to support the revolutionaries in Iran. Part two of this article explores this question as it relates to Marxist theorists specifically.

A. Implications of the Jina Uprising for Iran

In the eyes of its participants, the Jina Uprising holds immense significance. For example, on the 44th anniversary of the 1979 Revolution, a coalition of independent trade unions and civic organizations in Iran published a “Charter of Minimum Demands” that stated they conceived of the Jina Uprising as a movement that “intends to forever end the imposition of power from above and touch off a societal, modern, and humane revolution to free the people from all forms of oppression, discrimination, exploitation, and dictatorship.”[1]

Further, for six revolutionary committees in Iran, which met in conversation with Slingers Collective, a Marxist research collective, the end of the Jina Uprising means that “the revolution is an ongoing journey” that seeks to abolish “capitalism, patriarchy, and the concentration of power.”[2] Similarly, members of these committees said that revolution does not end until human beings are in control of “shaping their own destiny.”

The implication is that there is agreement that the revolutionary movement has not been defeated. The committees especially do not speak of the end of the revolution. Instead, they speak of “an opportunity to breathe,” reflect, and reorganize their thinking and organizations. They also mention that “a promising point is the growth of strikes and rallies” by workers and pensioners. Further, they celebrate the “oppressed nations, women, and finally industrial workers” who “have been brought to the center stage as a power,” an “unprecedented achievement in the last forty-four years.”

It is worth dwelling on this point for a moment. Not only was the uprising led by women and not only did men put their lives on the line for women’s freedom, the uprising marks a new stage of ethnic and religious solidarity. According to the Gilan Revolutionary Committee, the uprising “witnessed a nationwide solidarity, precisely among minor ethnicities and subalterns.” Further, the Street Militants Group mentioned that “freedom is one the main pillars of the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ movement, and it has opened ways for individuals of every religion, belief or faith to join this uprising.” These developments are important challenges to Persian and Muslim supremacism that have been a source of tension in the Iranian revolutionary movement since the Constitutional Revolution began in 1906.[3]

Finally, revolutionaries in Iran are talking about uniting the unions with the street organizations, establishing a balance of power with the state, and other next steps. Thus, it seems that the revolutionaries in Iran conceive of themselves as entering a new stage of struggle and have already begun to take responsibility for developing new ways of thinking to meet the historic challenge. However, much of the Marxist left has not. Thus, before examining the global implications of the Jina Uprising and WLF, I feel it is necessary to criticize an approach to social movements that dominates the Marxist left: simply passing judgements on them.

B. Problems with Passing Judgement

Unfortunately, this tendency can’t be said to belong to one group or current of Marxism. Thus, while I focus below on a Trotskyist—because he was one of the few Marxist commentators on the movement in Iran coming out of the country I live in, Canada, and because his article clearly demonstrates the approach I am criticizing—it must be noted that it is not a problem exclusive to Trotskyism. Rather, it is a problem of confusion about our responsibilities to social movements as Marxist theorists.[4] However, the problem with this approach is not just that it is dominant. It is also that it doesn’t offer anything new to social movements. Put bluntly, if Marxist theorists wish to be relevant to social movements, it is a tendency that must be overcome.

In an article on the Jina Uprising published in the online publication of the Canadian section of the Trotskyist International Marxist Tendency, Hamid Alizadeh derides those “on the Iranian left, in particular those from the Stalinist tradition” who judged that the movement was not worth supporting because of an “absence of a clear revolutionary leadership.” Alizadeh is right to oppose those on the Left who do not see the significance of the recent rebellion in Iran. Yet, Alizadeh does not approach the Jina Uprising in an altogether different fashion than those he criticizes. Instead of judging that the uprising can be dismissed, he judges that it is doomed without his political categories and thus tries to substitute these categories for the real self-development of the movement.

To help us understand the problems with this approach, I will repeatedly turn to the Preface of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. This is because central to the early sections of his Preface is a critique of passing judgment as a “type of doing” and “form of cognition.” At first glance, it may seem like Hegel’s Preface has nothing to do with the problems of Marxist theorists today. Hegel, at least at the outset of the Preface, is concerned with responding to those who demand an explanation of an author’s “purpose in writing the book, his motivations behind it, and the relations it bears to other previous or contemporary treatments of the same topics” (Preface S.1) because they, erroneously in Hegel’s view, deem these things to be “what is essential” (S.2).

Its relevance becomes more apparent when we remember two related points. First, “that for every stage of phenomenological development there is a corresponding historic stage.”[5] And second, “thought molds its experience in such a manner that it will never again be possible to keep these two opposites in separate realms.” In other words, while Hegel’s Preface begins as a criticism of different philosophical systems that fail to grasp “the development of truth” (S.2), it is also a treatise on how to think about reality and the development of history.

Sure enough, it is the development of history that Alizadeh is concerned with. In his article, “Iran: The need for a revolutionary programme,” Alizadeh asks, “Where does the movement go from here?” He answers that if the Jina Uprising is not to be crushed by the IRI or commandeered by Reza Pahlavi and his associates, a general strike “must be taken up and made the rallying cry of the whole movement.” Further, revolutionaries in Iran must unify “all the struggles into one movement” and “build a revolutionary organization on the basis of Marxist theory.” Finally, a “revolutionary programme” must be developed.

Unlike his Stalinist adversaries, Alizadeh does not dismiss the Jina Uprising outright. Instead, he says the task of “true communists and revolutionaries” is to “assist the movement in developing a programme and in building a leadership where none exists.” According to Alizadeh, this can only be done by “supporting and following the movement in its development and, in doing so, attempting to educate the best elements.”[6] But this article, written less than two weeks after the beginning of the Jina Uprising, doesn’t spend much time “supporting and following” the movement. In fact, the majority of the article is devoted to arguing that the movement will fail if the revolutionaries in Iran don’t do the things he outlines above!

International Marxist Tendency logo. Communist Revolution is the Canadian chapter. Source: Marxist.com

To give Alizadeh some credit, some of what he outlined in his article did develop later. For example, the “Charter of Minimum Demands” resembles the “revolutionary programme” he sketched in his article. Furthermore, Iran’s new generation of revolutionaries have built numerous organizations “on the basis of Marxist theory.” These organizations, however, have formed in opposition to the old Communist and Trotskyist parties. Yet, the problem remains that almost as soon as the movement began, Alizadeh judged it would be a failure and just as quickly proceeded to give his opinion on what could deter its sure defeat.

Hegel may have called these hasty judgments “little more than a contrivance for avoiding what is really at stake” (S.2). At worst, they are “an attempt to combine the semblance of both seriousness and effort while actually sparing oneself of either seriousness or effort” (S.2). To be clear, I am not trying to suggest Alizadeh is not a serious revolutionary or that he doesn’t put effort into his work. What I am trying to say is that if what is at stake is the development of the Jina Uprising, then Marxist theorists need to be serious about making sure the development of the Jina Uprising is our subject matter. Rushing to conclusions shifts the subject matter to something else entirely.

In this case, Alizadeh shifts the subject matter from how the movement has developed or could develop, based on emerging tendencies, to the tasks of revolutionaries, the results of the revolution, and what distinguishes his ideas from other Marxist tendencies. Herein lie some issues.

To declare what the tasks or aims of revolutionaries are while the development of the movement has not yet been “exhaustingly treated” (S.2) is to make those aims and tasks into “lifeless universal[s]” (S.2). In other words, because “revolutionary leadership” and “revolutionary programme” are always given as the path of development, regardless of the content of a social movement, they’ve become rigid abstractions. Similarly, without an exhaustive treatment of the movement, the results become a “corpse that has left the tendency” (S.2) of the social movement behind. That Alizadeh has left the movement behind is perhaps most strikingly clear at the end of his article, where he neglects to include “Woman, Life, Freedom!” but manages to slip in “Build the Revolutionary Leadership!”

For Hegel, this emphasis on purposes, results, and distinctions “instead of occupying itself with what is at stake…goes one step beyond it” (S.2). For example, Alizadeh, instead of occupying himself with the self-development of the mass movement, has thereby begun to occupy himself with “revolutionary leadership” and “programmes.” Put another way, “instead of dwelling on the thing at issue and forgetting itself in it, that sort of knowing is always grasping at something else” (S.3). If not the “movement in its development,” what is Alizadeh grasping at?

The continued relevance of Trotskyist categories. Instead of dwelling on the “movement in its development,” as Alizadeh claims he is doing, and forgetting his private interests and preconceived notions about what revolution looks like, he passes judgements that “prove” his tendency’s categories are necessary. The specific problem with the refusal to reorganize his categories is that they leave no room for the fact that a new generation of revolutionaries in Iran comprehends that they are their own leaders and are building new organizations to give this self-conscious leadership objective expression. The more general problem with refusing to reorganize one’s categories is two-fold: it precludes the development of thought and, in doing so, limits the possibilities of self-development ‘on the ground’ in a revolutionary situation.

This leads us back to the problem of passing judgment. Passing judgment does not work towards “the development of truth,” in Hegel’s words. For this reason, it does not assist social movements. Instead, it works to protect the lifeless categories and routine conclusions that have Hegel refers to as corpses. For example, Stalinists can denounce the Jina Uprising, so they don’t have to confront the limits and problems of their own philosophical system. Similarly, Alizadeh can quickly judge that the revolution will fail without accepting his categories. Then, if the revolution fails, he can blame the movement for not adopting those categories. If it succeeds, he can point to the instances of revolutionary leadership and the programmes that will likely develop independently. Whatever the outcome, the conceptual categories stay the same. The movement of thought is arrested and nothing concrete is offered to the revolutionaries in Iran.

C. Global Implications of “Woman, Life, Freedom”

If we refuse to rush to conclusions, it is apparent that the Jina Uprising and WLF are important not just for Kurdistan and Iran, but the entire world. This is made clear by their global reception and, importantly, their global implications. For example, Mojtaba Mahdavi refers to WLF as a “glocal” phenomenon. Further, Mahdavi also quotes the public intellectual Slavoj Zizek, who said, “We can immediately see that the Iranian struggle is the struggle of us all.” Mahdavi also mentions Michael Hardt, who described WLF as a “supplement’” and “reinterpretation” of the “French Revolutionary slogan: ‘Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.’” Whatever one may think of these two figures, they correctly identify the universal quality of the uprising and WLF.

Iranian human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh provides some insight into why the Jina Uprising has moved women all over the world. She discusses how WLF reflects the struggle of women on an international level: “[Iran’s] mandatory hijab law forces us to cover our heads whenever we are in public, but it is also a way conservative forces try to exert political control.” This control, Sotoudeh continued, “ensnares men, not just women” and “may resemble what you experience in the fight for reproductive rights in America.” In other words, women around the world may have seen their own freedom being fought for in Iran.

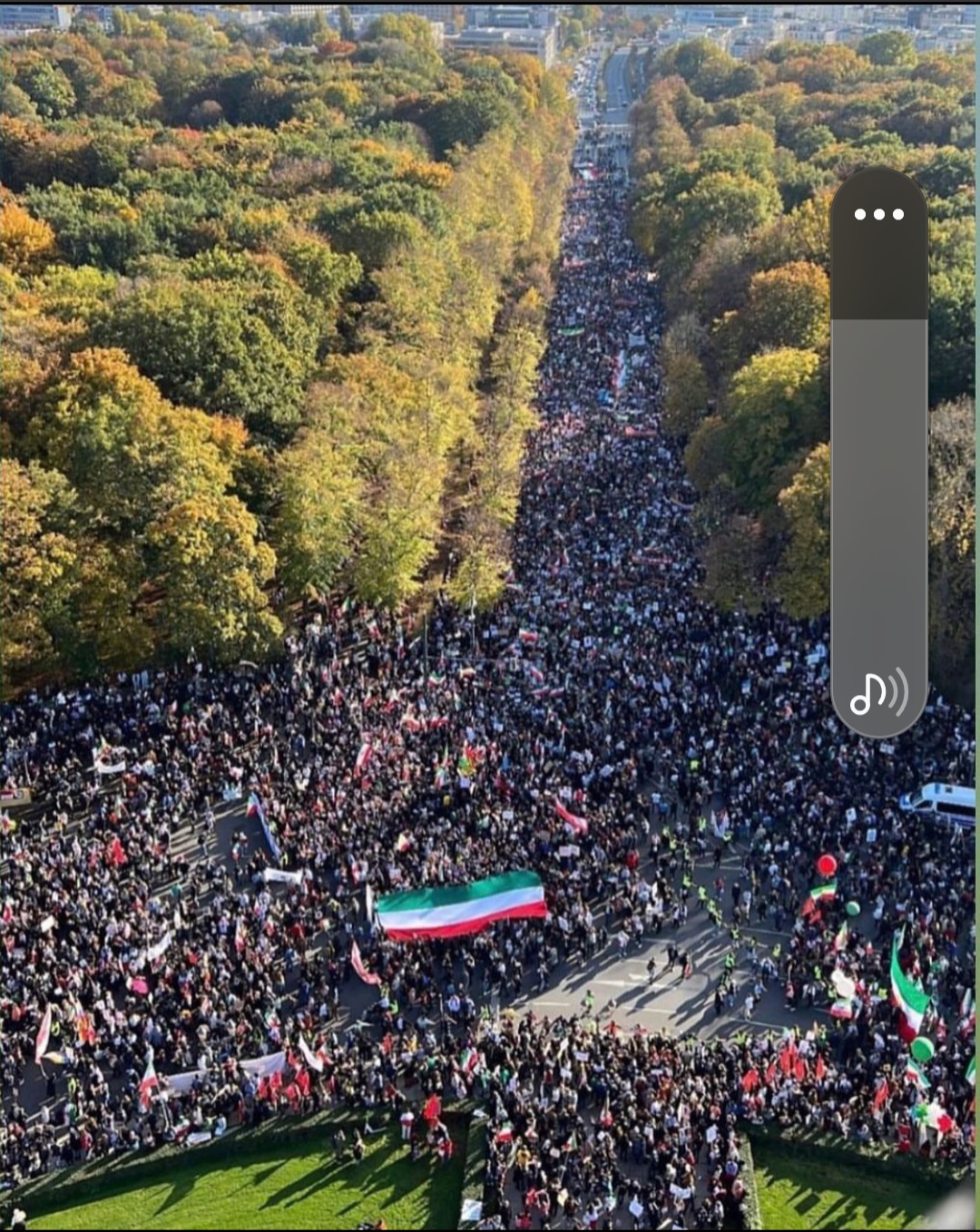

Solidarity Demonstration in Berlin. Credit: Woman* Life Free Collective

Shabnam Holliday elaborates on the international import of WLF in her article “Iran’s ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ Movement Highlights Global Issues.” She argues that “Iran’s current protests are not only significant because they challenge the Islamic Republic as a political system. They also challenge assumptions in global politics.” There are four assumptions that Holliday emphasizes. The first is that the movement in Iran poses challenges to “other regional powers that use an understanding of Islam to justify the survival of an authoritarian political system.” “Beyond the Middle East,” writes Holliday, “such a revolution challenges assumptions about who ‘owns’ democracy, progressive politics, and feminism. It is not just the ‘West.’”

Third, Holliday writes that “the rejection of the Islamic Republic as a political system also indicates the rejection of the Islamic Republic’s narrative of anti-imperialism.” In her words, this “challenges other nominally post-colonial projects built on ‘anti-imperialism’ and ‘anti-westernism,’ such as those of Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad.” Finally, she writes that “the current protests and demands demonstrate that the legacy of colonialism can be appreciated and addressed alongside a human desire for dignity.” WLF, then, is an attack on patriarchy but also authoritarianism, racism, colonialism, and pseudo anti-imperialism.

Holliday concludes that “Iran’s ‘woman, life, freedom’ uprising highlights battles over the values that govern world order and global politics.” In other words, the implications of the Jina Uprising and WLF are global. I share Holliday’s conclusion. In fact, I would even go so far as to argue that the Jina Uprising and WLF represent a historical crossroads between the defence and expansion of women’s autonomy, human and non-human life, and freedom itself and the continued rise of reaction around the world. It is on this point that I will conclude the first part of this article.

D. “Woman, Life, Freedom” at a Crossroads

There is no question that all over the world, we are facing a resurgence of reaction. From the Russian invasion of Ukraine to the repeal of the Dobbs decision and the existential threat to liberal democracy that Trump represents in the United States and from the election of a far-right president in Argentina to worsening ecological devastation all around the world, it is clear that women’s autonomy, human and non-human life, and freedom itself are being threatened. What is so significant about the Jina Uprising and WLF is that it offers an alternative path, not only to this future of misery and possible annihilation being projected by reactionary forces all over the world but also to those on the left who are refusing to confront these forces directly or who are searching for short-cuts to the new society.

Though the slogan of WLF originated in the Kurdish movement for national self-determination, it spread to the Iranian movement through “direct and concrete links” between women in Rojava and Rojhilat, Iranian Kurdistan. Since the Jina Uprising, revolutionary groups in Iran have been elaborating on the meaning of WLF. One of the few groups whose statements have been translated into English, Militants of Central Khorasan (MCK), articulated their conception of WLF in opposition to a coalition of liberals and monarchists in the diaspora formed around Reza Pahlavi. These militants declared that “woman” represents “a break from the sovereignty of religion and any form of paternalism” and a rejection of “all forms of centralism and autocratic leadership, be it Supreme Leader, Shah, Imam, patriarchal system or political party.”

MCK describes “life” as “going beyond the stage of necessities and entering the realm of freedom.” For them, life signifies “seeking equality and comprehensive justice” and “establishing preliminaries which are every human’s primary and natural rights.” Speakers from the committees who attended the Slingers conversation added to this concept of “life” the necessity to address environmental issues. While “free and high-quality education” and “free healthcare, decent housing, permanent employment, [and] retirement planning” are redistributive demands, in the Iranian context, they are revolutionary. This is because they are conceived of not as reforms to the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) but as projections of the future society after the fall of the regime.

Demonstration of mourning on the 40-day anniversary of Jina Amini’s Murder. Credit: Amnesty International

Finally, of “freedom,” MCK states: “liberation of human beings from any constraint that binds thoughts…freedom means the freedom of dissidents, it means the possibility of establishing political and cultural institutions…the right to protest and strike.” It means “the direct, immediate involvement of people in the self-determination process” and it implies “management by workers’ councils at national and regional levels.” Freedom, then, is not just the end of the IRI. It is the end of class society.

This emerging vision of total social transformation, along with the forces who led and participated in the uprising, link the Jina Uprising with the 1979 revolution. Raya Dunayevskaya wrote in her 1981 article “What Has Happened to the Iranian Revolution? Has it Already Run its Course into its Opposite, Counter-Revolution? Or Can it be Saved?” that Khomeini was a “second shah” who, with his Islamic Republican party, was trying to “complete the counter-revolution.” But she also identifies the true revolutionary forces: “from the proletariat to the peasantry; from the minorities, especially the Kurds, hungry for self-determination, to the women’s liberation movement; from the revolutionary intellectuals fighting for freedom of the press to the youth who have always been the vanguard in the revolution.”[7] It is these exact forces that are today fighting for the overthrow of the Islamic Republic.

Yet, just like the 1979 revolution, there is no guarantee that these forces will triumph over the forces of reaction. There is also no guarantee that the vision of WLF will continue to develop and win out against the IRI, competing anti-Khomeini forces like Reza Pahlavi, and imperial powers who may be waiting for an opportune moment to install a puppet regime. Further, it is a possibility that the counter-revolution could emerge from within the ranks of the new generation of socialists and feminists. To safeguard against this possibility, Dunayevskaya’s said in her 1981 article that the revolutionary forces in Iran must be “armed with a philosophy of revolution” to “initiate the road to classless society on truly humanist beginnings.”

The Jina Uprising shows that this philosophy of revolution is developing underneath the banner of WLF. But because no movement is immune to detours or retrogression, it is not enough for Marxist theorists to sit back and merely observe what is going on in Iran. Instead, it is our responsibility to help the revolutionary forces there further develop their philosophy of liberation. The question of how to do this is what I will turn to in part two, “On the Idea of ‘Woman, Life, Freedom.’”

Notes

[1] Emphasis added.

[2] Emphasis added.

[3] For a thorough discussion of the Constitutional Revolution see Janet Afary’s “The Iranian Constitutional Revolution: Grassroots democracy, social democracy, and the origins of feminism.”

[4] I return to this in greater detail in part two: On the Idea of “Woman, Life, Freedom.”

[5] Dunayevskaya, R. (2015). Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre, and from Marx to Mao. AAKAR Books. See especially, Section A. of Chapter 1: “Why Hegel? Why Now?”

[6] Emphasis added.

[7] Emphasis mine.

Be the first to comment