by MHI

Adopted by the Membership of Marxist-Humanist Initiative, December 5, 2021

“We must find a smooth transition to a low carbon economy.” “There is no planet B.” There is no planet blah. Blah blah blah …. “Build back better,” blah blah blah, “Green economy,” blah blah blah.

––Greta Thurnberg, Youth4Climate Summit, Italy, 2021

Greta Thurnberg has a knack for statements that cut-through the bullshit; and the above quote is no exception. Politicians have been making statements, promises, proposals and plans for many years now––but it is all bullshit, and those with the most at stake in the issue know it.

Humans have known about the dangers of emissions-driven climate change since the 1970s, yet virtually nothing has been done to avert the crisis. In recent years, it has become clear that the crisis is no longer something to speak of in the future tense. It is happening now. The scientific literature is increasingly alarming on this point. Yet the pledges and promises of leaders continue to fall short of anything approaching a solution. We all know by now that the promises of political leaders are nothing more than “blah blah blah.”

This Perspectives statement attempts to cut through the bullshit by illuminating the fundamental driver of ecological crisis, capitalist production’s inherent drive to expand material production beyond sustainable limits. As will be demonstrated below, it is extraordinarily unlikely, if not impossible, for society to transition to sustainable forms of production in order avert the multiple impending ecological crises while at the same time following the expansionary logic of capitalist accumulation.

This is a reality that not all in the environmental movement have come to terms with. Much of the environmental movement is concerned with the political problem of pressuring the fossil-fuel funded leaders of capitalist states to regulate and tax pollution and to invest in green technologies. But even if these movements successfully overcame the daunting political obstacles in their way, such reforms would fail to forestall catastrophic climate change, mass extinction, and multiple resource crises. This is because there is a much more fundamental problem lurking in plain sight behind the political problem: the endlessly expansionary nature of capitalist production.

It is hard to overstate the enormity of the crisis. In fact, it is not even one crisis, but an intersection of multiple crises, all playing out at the same time. In the near future, a warming planet will make many populated parts of the earth uninhabitable, flood cities, destroy agricultural production, spawn increasingly apocalyptic weather patterns, and create massive global refugee crises. Meanwhile, the planet is in the midst of its sixth species-extinction crisis, the first ever to be caused by human actions. This will affect the food chain in devastating ways. Overfishing and warming oceans are destroying fish populations, threatening the food supply for millions of people. From the air, to the ground, to the depths of the ocean, not a corner of the planet is spared from the crisis.

All of these intersecting crises share a central problematic: capitalism is a system predicated on perpetual accumulation, constantly expanding the sphere of material production without any consideration of the ecological ramifications of this endless expansion. Capitalist growth is not only the prime driver of these intersecting environmental crises. It is also impossible for these crises to be solved while still pursuing the expansionary logic of capital.

The field of environmental theory known as “degrowth” or “post-growth” theory has correctly pointed to this endless growth for the sake of growth as the prime driver of ecological crises. This field has provided some excellent analyses of the empirical impossibility of decarbonizing the global economy while simultaneously pursing GDP expansion. Yet, as will be discussed below, because much of the degrowth movement has failed to grasp why capitalism is inherently expansionary, its proposed solutions fall far short of the transformation of the mode of production that is required to really address the issues at stake.

What Does Capitalism Expand?

Before answering the question of why capitalism expands, it is important to consider what capitalism expands. The inherent expansion of capital is an expansion in the size of production, aimed at increasing the profits accrued by capitalists. It is production for production’s sake. Capitalists do not expand production in order to create more wealth for society in general, expand the realm of human freedom, raise living standards, increase leisure time, or solve social problems. Rather, this expansion is an increase in the production of goods and services aimed at increasing the profits of capitalists.

GDP growth is commonly spoken of as something that is inherently good because it can lower unemployment and raise living standards. This can be the case. For this reason, capitalist states feel compelled to pursue policies of GDP growth in order to raise the living standards of their citizens. But these are not the intended consequences of capitalist production and accumulation. Because such economic benefits are by-products of capitalist growth, they are distributed unevenly and haphazardly, always reproducing the inequalities of capitalist society and always at risk of evaporating in the next economic downturn.

And, of course, another unintended side-effect of economic growth is environmental destruction. The more capitalist production expands, the more energy and material resources it consumes and the more carbon emissions and waste it produces. Pollution and resource use mean nothing to capitalist production unless they affect the rate and mass of profit. Depletion of resources can enter into the calculations of capital if it leads to a rise in the cost of resources. And pollution can enter into the calculations of capital if states impose taxes on pollution. But the health of ecosystems themselves have no inherent value to capital.

Why Does Capitalism Expand?

Why do capitalists recklessly expand production in the pursuit of greater profits, even when their activity is socially destructive and it threatens the stability of the ecosystems that society relies on for survival? They certainly don’t do it because of subjective motivations like greed and ambition or because of a psychological condition. If capitalism had a psychological diagnosis, it would likely be Antisocial Personality Disorder. But capitalists themselves can be perfectly well-adjusted people while at the same time benefiting directly from the most anti-social, apocalyptically reckless activity. It is worth recalling Marx’s method in which

individuals are dealt with only in so far as they are the personifications of economic categories, embodiments of particular class-relations and class-interests. My standpoint, from which the evolution of the economic formation of society is viewed as a process of natural history, can less than any other make the individual responsible for relations whose creature he socially remains, however much he may subjectively raise himself above them.[1]

As personifications of economic categories, capitalists’ behavior merely executes the internal laws of capitalist production. In the formula M–C–M (in which money is exchanged for commodities which are then sold for money), the process would be pointless unless it resulted in a greater amount of money at its conclusion. Thus, Marx characterizes the general formula for capital as M–C–M⸍ (in which capitalists invest in the production of commodities which are then sold for more money than the original investment). Since the goal of production is not the creation of specific use-values, but the increase in the size of the initial investment, “the circulation of money as capital is, on the contrary, an end in itself, for the expansion of value takes place only within this constantly renewed movement. The circulation of capital has therefore no limits.”[2] In fact, capital is indifferent to the use-values it creates. Whether it produces oil, atom bombs or lollipops, these use-values are just a passing phase in the transformation of money into more money.

However, this indifference to use-value and this incentive to produce for profit does not wholly explain why capitalists are compelled to reinvest their profits in the expansion of production. Capitalists could decide to waste all of their profit in luxury consumption rather than reinvest it in the expansion of production. But they do not. The pressure of competition between capitals compels capitalists to constantly seek to accumulate more, expand production, capture more market share, revolutionize technology, decrease production time, and command more resources. Capitalists who stand still and ignore the compulsion to grow are eventually destroyed or consumed by the competition. As Marx put it:

The battle of competition is fought by the cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities depends…on the scale of productivity of labor, and this depends on the scale of production. Therefore the larger capitals beat the smaller.[3]

The larger capitals beat the smaller because of economies of scale. There is an inherent advantage to a larger scale of production in the battle of capitalist competition. A larger scale of production allows for a decrease in the production cost of a unit of output, allowing capitalists to sell below the price of competitors and to capture more market share.

Marx argues that “the development of the productivity of social labor becomes the most powerful lever of accumulation.”[4] The social productivity of labor is measured as the number of things a worker can produce in a given amount of working time. As productivity increases, more commodities can be produced in a working day, so the unit price of commodities tends to fall, allowing capitalists to compete in the battle of competition. Every increase in productivity means that more capital must be invested in raw materials as well as in new means of production capable of increasing productivity. Thus, as capital accumulation proceeds, a greater and greater proportion of investment is devoted to the non-labor inputs into the production process, which Marx called “constant capital,” relative to the labor inputs, which Marx called “variable capital.” This ratio of constant to variable capital is called the “organic composition of capital.” Empirical data confirms Marx’s claim that the organic composition of capital rises as accumulation proceeds.[5]

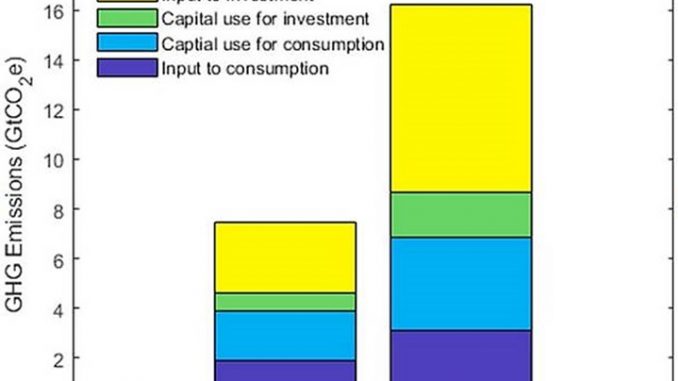

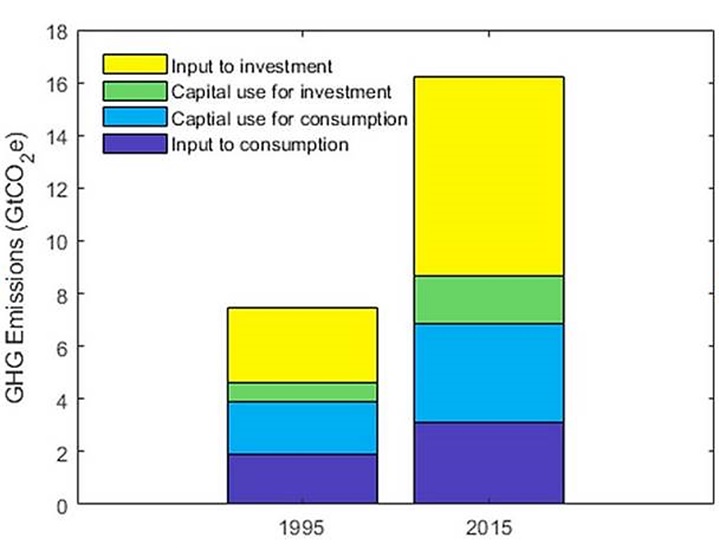

As accumulation increases the scale of production, this results in greater use of material inputs and rising carbon emissions. And because production of means of production tends to grow faster than production of consumption goods—which reflects the fact that the organic composition of capital is rising––it is likely that production of means of production, not production of consumption goods, is becoming a larger and larger source of capitalist production’s growing carbon footprint. Recent empirical data backs this up; between 1995 and 2015, the carbon footprint of consumption rose by 64%, but the carbon footprint of investment rose by 170%, more than two-and-a-half times as rapidly (see bar graph below). In other words, the greenhouse gases created by capital formation are increasing much more rapidly than the greenhouse gases created by consumption.[6]

So capital accumulation, in which profits are reinvested in the expansion of production, is an expansion of productive activity driven by the competition between capitalists. The social, political, and environmental effects of this process are side effects that have no inherent bearing on the drive to endlessly accumulate; they factor into the reinvestment decisions that capitalists make only in the event that these side effects affect the cost of production. And the most important lever of accumulation, labor-saving technological change, leads to a change in the organic composition of capital, such that a greater and greater proportion of investment flows toward the consumption of raw materials and the construction and maintenance of means of production, further accelerating the degradation of resources and release of carbon emissions.

“Accumulation for accumulation’s sake, production for production’s sake”[7] is thus a fact of capitalist production. It is not something that can be reformed away. Only a change in the mode of production can put an end to this mad imperative to recklessly accumulate at all costs. In other words, only a change in the mode of production can overcome the problem that capitalists will not adopt any innovations that reduce profitability, even those that would allow economic growth to proceed in a sustainable manner. (To be clear, we are not opposed to growth under non-capitalist conditions. After all, there is no other way to substantially raise the standard of living of the world’s poor.)

“We Have the Answers. Now We Need To Stop Talking And Do It”

Despite the central role that capitalist accumulation plays in ecological crisis, it is uncommon to hear discussion of overthrowing the capitalist mode of production in discussions about the climate crisis. It is common to hear the argument that we already have the answers to the ecological crises at hand, so that all that is needed is the will or political power to put these existing ideas into motion.

Take, for instance, Andreas Malm, known for his militant environmental views, who argues in his 2020 book that

everybody knows what measures need to be taken; everybody knows, on some level of their consciousness, that flights inside continents should stay grounded, private jets banned, cruise ships safely dismantled, turbines and panels mass produced––there’s a whole auto industry waiting for order––subways and bus lines expanded, high-speed rail lines built, old homes refurbished and all the magnificent rest.[8]

Greta Thurnberg also echoed this idea in a 2018 TedTalk: “But the climate crisis has already been solved. We already have all the facts and solutions. All we have to do is to wake up and change.”

This notion is implicit in the politics of many of the activist environmental organizations. The Sunrise Movement, for instance, is an organization entirely devoted to building political power. It has intensive organization-wide discussions about political strategy, how to build the organization, and how to influence policy. The assumption is that we already have the ideas we need, in the form of a Green New Deal, so all that is needed is emergency mass action to force leaders to put these ideas in practice.

Indeed, we do need emergency mass action. And we do need to take all measures possible to transition to green technologies as rapidly as possible. But implicit in this conception are the notions that the changes required to solve these crises are merely technological changes and that the obstacle to be overcome is one of politics. Thus, if we had better leaders, propelled to action by a radical environmental mass movement, we could replace our fossil fuel technologies with green technologies and the problem would be solved.

There is nothing more reeking of bourgeois ideology than the idea that we can solve social problems, problems of the organization of social productive relations, through merely technical fixes. Because of that ideology, we are inundated, day in and day out, with promises of the wonders that await us with the release of every new innovative gadget.

There are also non-ideological factors that make technological innovation centrally important to capitalism. The central social conflict of capitalism, that between capital and labor, is an antagonism that capital, since the dawn of capitalism, has sought to overcome by means of the miracle of labor-saving technology. And, as discussed above, labor-saving technological innovation is also “the most powerful lever of accumulation.”

So it is natural that we would turn to technical innovation as the solution to ecological crisis. After all, our current technologies are destroying the planet. Clearly, they must be replaced with more sustainable technology.

Yet the biggest decrease in carbon emissions ever did not come from technological change. In 2020, global carbon emissions fell by 7%, reducing the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by 2.4 billion metric tons. This was the direct consequence of COVID-related lockdowns and restrictions. Global GDP fell by 3 trillion US dollars in 2020 and, as the gears of capitalist production slowed down, so did the release of planet-warming emissions.

Obviously, infectious diseases are not the solution to ecological crises. However, the direct relation between GDP growth and emissions is strikingly illustrated by the experience of the 2020 pandemic. When the capitalist economy slows down, so does pollution. This illustrates a central problematic: capitalism’s limitless appetite for growth comes at the direct expense of the planet. Unrelenting growth that proceeds anarchically––that is, without regard to its environmental impact––is not something that can be fixed merely by technologies, because it is a question of the economic organization of society. It is not “fossil capitalism.” It is just “capitalism.”

Delving into the details is illustrative of the problem. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement of 2016 commits the world to keeping global warming to no more than 2°C above preindustrial levels (though the emission reduction commitments of the same agreement are not substantial enough to actually meet this goal). To reach this goal, global emissions would need to be reduced by 4% per year.

But the economy is growing, somewhere in the range of 3% per year globally. Historically, GDP growth is closely coupled with growth in greenhouse gasses (GHG). Global GDP grew by 3.5 per year from 1960 to 2014, while CO2 emissions rose by 2.5 per year on average. From 2000 to 2014, GDP and CO2 emissions both grew by an average of about 2.8% a year.[9] This coupling of GDP growth with carbon emissions is an inevitable product of the fact that so much of capitalist production relies on fossil fuels.

In order for GDP to grow and carbon emissions to fall, economic growth would have to be decoupled from carbon emissions. This has produced a debate over the possibility of decoupling GDP growth from emissions and/or resource use. On one side, there is the theory of “green growth,” which claims such decoupling is possible. On the other side are the degrowth or post-growth theorists who argue that this decoupling cannot happen fast enough to meet the UNFCCC’s 2°C target.

Degrowth theorist Jason Hickel describes the crux of the problem this way:

In order to … keep within the carbon budget for 2°C, the world will have to make much more aggressive reductions in CO2 emissions, at a rate of 4% per year. Theoretically, this can be accomplished with a total shift to renewable energy (see Jacobson & Delucchi, 2011). The question is, can this be done rapidly enough against a backdrop of economic growth? If the global economy grows by 3% per year … then achieving emissions reductions of 4% per year requires decoupling (or decarbonization) of 7.29% per year. For reference, World Bank data shows that global carbon efficiency (CO2 per 2010 $US GDP) improved at a rate of 1.28% per year from 1960 to 2000. In order to stay under 2°C, then, decarbonization needs to occur six times faster than historical rates. And it is important to note that the rate of decarbonization has not improved in the 21st century; World Bank data shows that from 2000 to 2014 there was zero improvement in global carbon efficiency.[10]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change does show scenarios in which we can stay within the 2°C limit while growing global GDP. However, these scenarios rely on the controversial technology known as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), a solution to climate change promoted by oil companies. In addition to the fact that BECCS has not been shown to be economically viable at scale, BECCS plantations would require huge amounts of land in order to offset GHG emissions. By some estimates, BECCS plantations would require land 2–3 times the size of India.[11]

The difficulty of decoupling GDP growth from environmental degradation is not just limited to the issue of carbon emissions. It also appears in the pursuit of achieving a sustainable material footprint. In 2015 the global material footprint consumed by humans was 87 billion tons of the earth’s resources.[12]In 2019 humans consumed 100 billion tons. Assuming 3% GDP growth, this would rise to 167 billion tons a year by 2030. There is some consensus that a sustainable annual footprint would be around 50 billion tons a year. (Unfortunately, material efficiency has actually been getting worse rather than better in recent years.) In order to reach the goal of 50 billion tons, we would need to reduce annual resource use by 3.63% until 2030. If GDP is simultaneously rising at 3% a year, this would actually mean a reduction of 6.88% a year in resource use per unit of output, a rate of efficiency improvement that is 3 to 6 times higher than anything ever before achieved in the history of capitalism.[13] In the examples of both carbon emissions and material footprint, we can see that relatively “normal” GDP growth makes the goal of decoupling out of reach, only achievable in some sort of hypothetical scenario in which there is an unprecedentedly rapid switch to new green technologies.

Even if there was some remarkable breakthrough and adoption of more efficient technology, this still doesn’t necessarily solve the problem posed by capitalist growth. There is still the problem of the Jevons Paradox, in which increases in efficiency lead to falling prices, which then lead to increased demand, which in turn causes an increase in consumption.[14] Jevons wrote about this paradox in his 1865 book “The Coal Question,” where he observed that the introduction of the Watt steam engine, which improved the efficiency of coal-powered steam engines, led to a much more widespread use of coal despite the rise in efficiency. An often cited contemporary example of this is the observation that increases in the efficiency of light bulbs have led to wider use of lighting and therefore more consumption of electricity rather than less. There have been remarkable gains in efficiency in many areas over the past 100 years, from fuel consumption, to refrigeration, to lighting, to computing, to heating, etc. But in each of these areas, the increase in efficiency has not led to a decrease in the consumption of energy.

The naiveté with which some cling to technological solutions to save us from the contradictions of capitalist social relations can result in absurd fantasy, even among the left. Take, for example, the technological determinism of Aaron Bastani, who made somewhat of a splash in recent years, with his call for a “fully automated luxury communism,” in which an enlightened welfare state develops production toward full automation completely powered by solar technology. With humans freed from work, and with the sun’s free energy providing all the power we need, this fully-automated luxury communism could expand forever, or so Bastani claims. This transition to a world of abundance and limitless growth is made possible not by social revolution but by the inevitable, teleological progress of technology.

Yet none of the ecological problems our world faces are solved through Bastani’s technological utopianism. In a world of supposed abundance, where efficiency and automation make energy and goods free, how do we escape the Jevons paradox? How do we limit production and consumption to sustainable levels? Even solar panels require natural resources like lithium and cobalt. Bastani’s answer: “the limits of the earth won’t matter anymore––we’ll mine the sky instead.” Bastani proposes mining asteroids for these minerals. As Ville Kellokumpu, a critical reviewer of his work, remarked, “When the soil beneath our feet is becoming toxic, it is easier to look up than down. The logic is expansionist, as with capitalism.”

Taking refuge in fantasies of technological salvation does us no good when faced with the reality of a social system that is predicated on growing beyond ecologically sustainable boundaries. Asteroid mining, carbon capture, cloud seeding, air scrubbing, low-methane cows … the list of miracle cures goes on and on. At best, such technologies can only forestall the inevitable confrontation between capitalism and the planet.

Build Back Better, Green New Deal, Green Growth

Given such considerations, it is hard to see how, for instance, US President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan will stand a serious chance of adequately reducing the US’s carbon footprint. The plan aims to reduce GHG emissions in half by 2030 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. At the same time, it aims to increase economic growth, with some analysts predicting the plan would increase US GDP.

Much of the US environmental movement is now focused on pressuring Congress to pass Biden’s plan, in hopes that it will be the first step in the construction of a Green New Deal (GND)––a more ambitious group of proposals that progressives, especially social democrats, advocate.

There is no question that we need a massive transformation of our infrastructure and energy production in order to transition away from fossil fuels. Yet one must also pause and consider the irony of an environmental movement that harkens back to the image of the New Deal. Setting aside the historical question as to whether the New Deal was actually responsible for the postwar economic boom, it is certainly the case that the populist left has often claimed that the New Deal spurred economic growth. And while GDP growth is not explicitly listed as a goal of H.Res.109 (the Ocasio-Cortez, Markley House Resolution calling for a GND) “the idea is implicit in its goals to ‘spur economic development’ and ‘to grow domestic manufacturing.’”

The economic expansion of the US and world economies of the postwar period was an environmental disaster. The growth of industrial production, suburbanization and rising incomes led to more resource use and more carbon emissions. The US, with 5% of the world’s population, now consumes 17% of the world’s energy. If the entire world’s population had a standard of living equal to that of the average US citizen, it would require over 5 planet Earths’ worth of resources to maintain that level of consumption. With such glaring global inequalities in consumption and ecological footprints, we must stop to consider the wisdom of selling every populist economic plan with the promise that it will increase economic activity and raise living standards. Not only is this an ecologically disastrous means of addressing the social problems of capitalism, but capitalist growth will never solve these problems anyway. The growth of capital merely reproduces inequality and exploitation on an expanding scale.

So Close, Yet So Far Away

The school of thought known as degrowth or post-growth economics contains a fairly wide spectrum of ideas and claims. But one thing that unifies the field is the idea that economic growth for its own sake is not compatible with the goals of environmentalism. When one considers the basic facts of the matter, it is hard to see any rational way to reconcile endless capitalist growth with human life on planet Earth. Many in the degrowth milieu explicitly argue that, because this mindless growth is inherent in capitalism, capitalism is incompatible with the goals of environmentalists.

In this respect, degrowth critics of capitalism have identified a key aspect of capitalism that is often ignored, not just by mainstream environmentalists but also by the social-democratic, populist left. The left is often preoccupied with inequality and the critique of markets or neoliberalism. But accumulation for its own sake has been a feature of capitalism regardless of the level of inequality, the mix of planning and markets or the neoliberal/Keynesian/social-democratic orientation of leaders. Accumulation for its own sake was a central feature of the state-capitalist societies often referred to as “20th-century communism.” Endless accumulation is in the very DNA of capitalist society. And, as mentioned above, the populist left often attempts to sell its programs with promises of economic growth.

Yet despite how clearly degrowth theorists perceive the necessary link between capitalism and accumulation, they have failed to perceive why capitalism and accumulation are necessarily linked.

The more naive tendency amongst degrowth theorists is the tendency to argue that solutions to the ecological crisis will arise merely by abandoning GDP growth as a policy objective––as if capitalist accumulation were the result of conscious choices made by growth-minded politicos,[15] rather than the inevitable result of capitalist competition. This is pure fantasy. Politicians are compelled to encourage growth because recessions generate social misery and political instability. There is no realistic option, within the logic of capitalism, to legislate negative economic growth.

Despite plenty of good arguments as to how basic human needs and freedoms are not measured by GDP, despite plenty of insights into how more sustainable levels of consumption and resource use could benefit humanity in ways not measured by GDP, the degrowth literature seems unable to grapple with the idea of capitalism as a mode of production.[16]

Thus, for degrowth theorists, the solution to the ecological crises is a raft of regulations, taxes, redistribution, and state ownership of some industries.[17] Although this is often more radical than the reforms demanded by social democrats, it still shares the same conception of “anti-capitalist” politics that social democrats hold. It is a vision that treats the symptoms but not the disease.

Capitalism is a mode of production. The law of value that lies at the heart of capital operates regardless of whether the state is redistributionist or neoliberal. The law of value exerts its force upon society whether or not production is privately owned or state owned. The tendency for capitalism to reproduce capital and capitalist social relations on an ever-expanding scale is a fundamental law of capitalist production.

The actions of the most well-intentioned leaders are still always forced to deal with the basic realities imposed by the law of value. One aspect of this reality is that a capitalist economy that does not grow goes into crisis. Of course, it is very common for environmentalists today to talk about a just transition for fossil workers, to demand green jobs, etc. But this is posed as an issue of transition––a period of adjustment as jobs move from some sectors to others. Yet if we recognize endless capitalist accumulation itself as a (or the) central problem, then we aren’t just dealing with a short-term, transitional problem. A capitalist state cannot impose a condition of negative growth upon an economy forever. Rising unemployment and poverty would lead to chaos and social upheaval.

It is not enough, as some have proposed, to nationalize key areas of production and to legislate shorter work weeks so as to equitably distribute work hours. Nationalized production is still capitalist production. A state firm can run a deficit, but only if taxes or bonds are filling in the gaps. And taxes and bonds rely on the production of surplus-value in other parts of the economy.

The fantasy of legislating degrowth through enlightened state policies rests upon the mistaken conception that the economic laws of capital can be overridden voluntaristicallly––without addressing the social organization of production that these laws arise out of. It is a persistent fantasy with a long history in left politics.

Its persistence may come from the fact that, for many people, it is hard to imagine truly breaking with the law of value, both conceptually and given the current political reality. The fact that the left has persistently ignored the need to further theorize breaking with value production, focusing instead on activism and movement building, has contributed to the problem. On the other hand, it is even harder to imagine a capitalist society overcoming its nihilistic destruction of the planet, reforming into some sort of sustainable social-democratic capitalism, mining asteroids for cobalt to build ever-expanding solar farms.

ENDNOTES

[1] Karl Marx, Preface to the 1st German edition of Capital, 1867.

[2] Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 1; p. 253 of Penguin edition (London: Penguin Books, 1990).

[3] Marx, ibid.; p.777 of Penguin edition.

[4] Karl Marx, ibid.; p.772 of Penguin edition. The development of productivity becomes the most powerful lever of accumulation because increases in productivity raise profits more reliably than would a mere expansion of production at a stagnant level of productivity. If productivity did not increase, the expansion of production would eventually lead to a rise in wages that would threaten accumulation. Increases in productivity allow for an increase in the relative surplus value extracted from workers as technological change lowers the cost of wage goods (thus cheapening labor-power). Technological change also allows capitalists to extract relative surplus value by producing their commodities in less than the socially necessary labor-time.

[5] The organic composition of capital in the US rose by an average of 1.7% per year from 1947 to 2009. See Andrew Kliman, The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession, London: Pluto Press, 2012 p. 133.

[6] See Figure 2 in Edgar G. Hertwich, “Increased Carbon Footprint of Materials Production Driven by Rise in Investments,” Nature Geoscience 14, 2021, pp. 151–155, and the accompanying spreadsheet, “Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2.”

[7] Marx, Capital, vol. 1; p. 742 of Penguin edition.

[8] Andreas Malm, Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency: War Communism in the Twenty-First Century, London and New York: Verso, 2020, p. 145.

[9] H. Haberl, et al., “A Systematic Review of the Evidence on Decoupling of GDP, Resource Use and GHG Emissions, Part II: Synthesizing the Insights,” Environmental Research Letters 15:6, 2020.

[10] Jason Hickel, “The Contradiction of the Sustainable Development Goals: Growth versus Ecology on a Finite Planet,” Sustainable Development 27:6, 2019, p. 5

[11] Hickel, ibid., p. 6.

[12] Hickel, ibid., p. 4

[13] Hickel, ibid.

[14] Matthew Soener, “Growth, Climate Change, and the Critique of Neoclassical Reason: New Possibilities for Economic Sociology,” Economic Sociology 22:3, 2021, pp. 10–15.

[15] Giorgos Kallis, Degrowth. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Pub., 2018. For instance, Kallis routinely suggests that a growth economy is the result of a “growth paradigm.”

[16] Jason Hickel, Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, London: Penguin Random House, 2021. For instance, Hickel claims that capitalism’s endless growth is a product of “artificial scarcity” that is imposed on society in the form of planned obsolescence, the separation of workers from the means of production, usury, etc.

[17] Hickel, ibid. His proposals include legislation to mandate extended warranties and a “right to repair,” so as to eliminate planned obsolescence, the “decommodification” of some industries through state ownership, and the shortening of the work week via legislation.

FN 4… “Technological change also allows capitalists to extract relative surplus value by producing their commodities in less than the socially necessary labor-time.”

Technological change also allows particular capitalists to extract extra-relative-surplus value by producing their commodities in less than the socially necessary labor-time.

Extra-surplus-value (Extramehrwert): The technological lead of particular capitalists allows them to extract extra-surplus-value by producing their commodities in less than the socially necessary labor-time. Other capitalists will have to catch up if they want to survive the competition. By this process they generate the continually moving societal level of socially necessary labor time. (MEW 25, Kapital Bd 1: 335-37). Penguin, Capital, vol I, 433-435. Thus, it is not technological change, but the edge in technological change that allows the respective capitalists to capture extra relative surplus value.

To prevent a structuralist misinterpretation of Marx’s work, it is important to note that personifications of economic categories (“Charaktermasken”, i.e. actors and actresses wearing masks that allegorically signal the message, mission and role they must translate into their theatrical performance) in Marx’s view are agents (not automatons) who are free in their management decisions, and their decisions require personal engagement and even creativity. However, their discretionary freedom abruptly ends when their purposes collide with capitalist necessities. In their acts as agents of categories they are driven by their motives, but they must constantly reshape their motives as required by the capitalist mode of production. If we look at the managerial agents, as one type of character-masks, the lawlike capitalist movens to produce profit at societal level must be turned into their subjective motive to do so, even if they are aware of the brutal consequences of their actions, and even if they ethically suffer from them. The agent may even succeed in re-interpreting his or her action as finally beneficial to all mankind.

However, this interpretation is always precarious, is repeatedly lost and re-found, and the agent as a personification of an economic category must continually reassure herself. This process of being torn apart into two beings, the actress behind the character-mask on the one side and the person in her individuality on the other side, characterizes alienated consciousness. Even the passage from Marx, cited in the MHI declaration, addresses this point: “however much he may subjectively raise himself above them [the economic laws, for the German-language reader: MEW 23: 16, MR]”. There is always a consciousness of difference between the individual hopes, ideals and ideas on the one hand, and the necessity to motivate oneself as a character-mask in the pursuit of profit on the other hand.

“As personifications of economic categories, capitalists’ behavior merely executes the internal laws of capitalist production” (MHI).

Yes, this is true. “Merely” however could leave the reader with a wrong impression. Individuals are more than personifications. To become personifications, they must impersonate themselves. They must internalize the structurally pre-given profit-motive. The managerial agents can execute economic laws only as highly motivated, creative individuals always prepared to make far reaching decisions, e.g. to rely on a risky innovation to capture extra-surplus value. In competitively doing so, they drive down the societal rate of profit, a process that in turn acts against them with the necessity of a natural law. Acting merely as automatons, the agents would be worthless and even dysfunctional. In Marx’s theory, even when he addresses economic laws as natural laws – as he sometimes does – agency is always present and is as important as structure, and his “psychology” addresses the dialects of capitalist consciousness, where the character-mask negates individuality, and individuality revolts against the mask. Far from disconnecting from the concept of alienation of the “young” Marx, the “mature” Marx offers a deeper understanding of alienation in capitalism. It is deeper, because it is now integrated into a consistent economic theory (for this consistency, see Kliman, Andrew. 2007. Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”. A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency. Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth UK: Lexington Books. For the German-language reader, see Kliman, Andrew. 2021. Die Rückgewinnung des Marxschen “Kapital”. Eine Widerlegung des Mythos innerer Widersprüchlichkeit. Übersetzung von Andrew Kliman Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital” 2007. Kassel: Mangroven Verlag.

Individuals, in Marx’s theory, be it “early” or “late”, “young” ore “mature” can throw away the mask, the working class can replace alienated consciousness by class-consciousness, and intellectuals can fight for free, unmasked thinking, as Marx himself did during his whole lifetime.

Thus, to change a passage in the MHI declaration: If capitalism had a psychological diagnosis, it would be alienated consciousness, rather than “Antisocial Personality Disorder”.

I want to emphasize however that the MHI-declaration is right in its general argument that protecting our natural environment demands for the abolishment of the law of value that governs the capitalist mode of production. Sociologist interpretations of Marx’s work are interested in the notion that objective structures building up behind the agents’ backs, independent of, and even contrary to their intentions (‘irony of paradoxical consequences’). Advocates of planned economies urge us to replace the anarchic build up of structures behind our backs by conscious centralized planning. The result of this approach is state capitalism where the law of value preserves its role or is even consciously re-instated. According to Andrew Kliman’s interpretation of Marx’s work, what builds up behind our backs is the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit, LTFRP, driven by the leading gains in productivity, with these gains in turn achieved by the competition among capitalists about extra-profits. The structural law they non-intentionally build up, the LTFRP, in turn necessitates new and increased efforts to produce profits, now under more difficult conditions, and their increased efforts will prepare the basic, underlying conditions of the next economic crisis, shining up us “financial crisis” (Kliman, Andrew. 2012. The Failure of Capitalist Production. Underlying causes of the Great Recession. New York: PlutoPress).

I agree with Michael Rednitz that Marx’s treatment of capitalists as personifications of capital has nothing to do with Althusser’s nonsense/revision, in which individuals are just effects of social structures, without agency, etc.

There’s a world of difference between saying that capitalists’ behavior merely executes the internal laws of capitalist production and saying that individuals (including, NB, non-capitalists) merely execute the internal laws of capitalist production. Individuals can, and sometimes do, choose not to play the social role of capitalist. Also, they can play that role for a time while violating the laws of capitalist production (e.g., not exploiting child labor although it’s cheaper and legal to do so), but then the action of competition ensures that they don’t continue to play that role; they go out of business.

Confusing “capitalists” with “individuals” or “people” goes hand-in-glove with the illusion that capitalism can become something it’s not, by putting different individuals, with different priorities, in control. As the above Perspective statement says, “The actions of the most well-intentioned leaders are still always forced to deal with the basic realities imposed by the law of value.”

Comrades,

I have one question related to this topic.

What do you think of the work of Jason W. Moore and his modification of key elements of Marx’s critique of political economy? I have noticed that he has gained some popularity in Marxist and environmental circles and that he is at odds with some of the Marxists, primarily Malm and Foster. Moore considers himself a Marxist. I find it strange that there are very few polemics about his work, especially Marxist ones, since he somehow modifies Marx’s theory of value. The law of value becomes the law of cheap nature, and the law of the tendency of the profit rate to fall becomes the tendency of the ecological surplus to fall. There is also the concept of negative value, and capitalism is defined not as a way of production but as a way of organizing nature.

While Foster and Malm disagree with Moore primarily on the problem of the relationship between nature and society, I have been able to find only one text that criticizes Moore from the perspective of Marx’s critique of political economy. It is a text by Jean Parker on ISJ, entitled Ecology and Value Theory.

This is an excellent article, but I would caution against an interpretation that implies we should ‘shrink’ everything, or hold ‘de-growth’ as a ‘better’ aim to capitalism’s growth model. Polarizing growth and de-growth is unhelpful and a limit to the ability to make these ideas ‘popular’ (yes, god forbid!) Moreover it is unnecessary and also untruthful. Rather than either ‘growth’ or ‘de-growth’, he new world economy is characterized by Reason as its principle, not a fetishization of either polarity.

Some things a post-value producing society would accomplish for example. include 100% switch to renewable energy (costs £72tn under capitalism and is thus resisted); rejuvenating the water network that under capitalism is decrepit, wasteful, and pollutive; innoculating cattle against bovine tuberculosis unlike the capitalist cull of hundreds of thousands of innocent badgers. These things are forms of expansion (from a certain point of view), not shrinking. Of course, with Reason, some things will ‘shrink’: there is no point to law, accountancy, finance – these sectors can be done away with. Also car use is less desirable if there is good, reliable public transport. On the other hand, agricultural production will expand (in a physical and productive sense) in order to feed a population of 7bn well. Rationality will do things that don’t harm nature, and rationality is set free by the products of labour ceasing to bear value, caused by the supersession of capitalist social relations wherein value is the mark upon the product of an estranged labour.