By Andrew Kliman, author of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A refutation of the myth of inconsistency

This article responds to recent works by Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, influential radical political-economic thinkers who teach, respectively, at York University in Toronto and at colleges in Israel. Part I, below, responds to Bichler and Nitzan’s (B&N) “Systemic Fear, Modern Finance and the Future of Capitalism” (Bichler and Nitzan 2010). In this paper, they argue that (1) “systemic fear”–fear of the death of the capitalism–has gripped capitalists during the last decade, but (2) capitalists’ belief that their system is eternal is necessary for its continued existence. So (3) the alleged systemic fear is itself a threat to the system. And thus we have yet another version of the notion that capital itself may be the historical Subject that will bring it down.

B&N claim that fear of the death of the system’s death has gripped capitalists only during two periods in recent history–the Great Depression and the 2000s. Their evidence for this claim consists entirely of the alleged fact that these two periods of crisis were the only periods since World War I in which equity (stock) prices and current profits were strongly correlated, i.e. the only periods in which they closely moved up and down together.[1] However, using the exact same methods and the exact same data as B&N, I show below that that equity prices and current profits were also strongly correlated from the early 1950s through 1973–during the so-called golden age of capitalism!

In Parts II and III of this article, which will appear here later this month, I will respond to the critique of Marx’s value theory that pervades Nitzan and Bichler’s 2009 book, Capital as Power. In this book, they allege that Marx’s value theory is practically useless for the study of accumulation. So my response will show, among other things, that his theory sheds significant light on the long decline in the rate of accumulation (investment) that contributed to ever-increasing debt burdens in the U.S. and helped set the stage for the recent Great Recession.

Part I

In November, Nitzan presented his and Bichler’s “systemic fear” thesis–including the correlation data that supposedly supports it—in a presentation to a joint session of the prestigious Harvard Law School and Harvard’s equally prestigious Kennedy School of Government. And a different version of the same argument, featuring the same correlation data, appeared earlier in an article they published in Dollars & Sense, a left-liberal economics magazine.

But since their data actually show that equity prices and current profits were also strongly correlated from the early 1950s through 1973–during the so-called golden age of capitalism!–we should doubt their claim that systemic fear has prevailed in recent years. After presenting and discussing these data, I will argue that flaws in B&N’s reasoning should also cause us to doubt their claim that capitalists are normally convinced that capitalism is eternal, as well as their claim that this conviction is crucial to its continued existence. But if the future of capitalism doesn’t hinge on the conviction that the system is eternal, it also doesn’t much matter whether capitalists have recently been gripped by systemic fear in B&N’s sense.

Good old regular fear, “the dread and apprehension that regularly puncture [capitalists’] habitual greed” (Bichler and Nitzan 2010, p. 18), is another matter. There can be little doubt that good old regular fear was intense at the start of the last decade, and even more intense at the end. I believe that this good old regular fear was justified and that it remains so. The underlying long-run economic problems that led to the recent Great Recession, and to the weakness of the subsequent recovery, have not been resolved. As I will discuss in Part II of this article, slow growth of employment relative to investment during the last six decades has led to a persistent fall in the rate of profit; the fall in the rate of profit has caused capital accumulation and economic growth to be sluggish for decades; and this sluggishness has led to mounting debt burdens. I doubt that the fall in the rate of profit can be reversed or that the debt problem can be solved without much more destruction of capital value–i.e. falling prices of real estate, securities, and means of production, as well as physical destruction–than has taken place to date. And if these problems remain unresolved, the economy will continue to be relatively stagnant and prone to crisis.

But it is difficult to discuss these ideas with B&N, or at all, because they and others like them contend that the theory on which the ideas are based, Marx’s value theory, is internally inconsistent and circular. An internally inconsistent theory cannot possibly be correct.[2] All ideas resting upon such a foundation can thus be disqualified at the starting gate, without further ado. In order to clear the ground for a genuine discussion–one in which B&N’s approach to questions of crisis and the future of capitalism is compared with and contrasted to something rather than nothing–Parts II and II of this article will respond to the main criticisms of Marx’s value theory.

* * *

B&N (2010, p. 17, emphasis in original) note that “if we adhere to the scriptures of modern finance, we should expect to see no systematic association between equity prices and current profits.” And they claim that equity prices have indeed become decoupled from current profits since 1917, except during two brief and exceptional periods. “Figure 2 and Table 2 show two clear exceptions to the rule: the first occurred during the 1930s, the second during the 2000s. In both periods … equity prices moved together–and tightly so–with current earnings” (Bichler and Nitzan 2011, p. 17 emphasis altered).

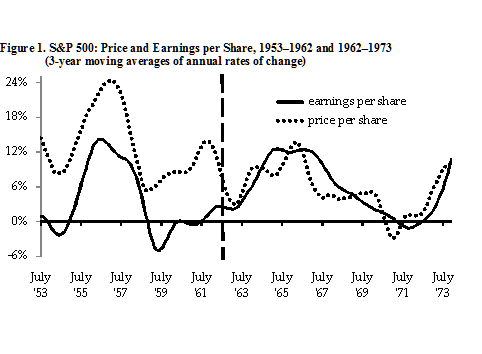

However, their Figure 2 actually shows four clear exceptions to the alleged rule. Equity prices also moved together with current earnings–and tightly so–from the early 1950s to the early 1960s, and from the early 1960s to the early 1970s (see my Figure 1).

During the first of these additional “exceptional” periods, period 4 of Table 1, below, the correlation between equity prices and current earnings was stronger than during the Great Depression (period 2). During the other “exceptional” period that B&N fail to bring to our attention, period 5, the correlation was lower, but still considerably stronger than during the 2000s (period 7).[3] The percentage of the variation in one variable that is “explained” by, or attributable to, the variation in the other is the square of the correlation coefficient, r2. Thus, as Table 1 shows, only about two-fifths of the variation in share prices during period 7 is attributable to variations in current profits; the explained variation during period 4 is almost twice as great, while the explained variation during period 5 is more than 50% greater.[4]

.

Table 1. Correlations between the annual rates of growth of stock prices and earnings per share, S&P 500 companies (monthly data are expressed as 3-year moving averages)

|

period |

no. of months |

correlation (r) |

share-price variation explained (r2) |

|||

| 1 |

Oct. 1917 |

– | Dec. 1929 |

146 |

0.29 |

8% |

| 2 |

Dec. 1929 |

– | Feb. 1939 |

110 |

0.89 |

79% |

| 3 |

Feb. 1939 |

– | June 1953 |

172 |

-0.34 |

12% |

| 4 |

June 1953 |

– | Aug. 1962 |

110 |

0.90 |

81% |

| 5 |

Aug. 1962 |

– | Dec. 1973 |

136 |

0.80 |

65% |

| 6 |

Dec. 1973 |

– | Sept. 2000 |

321 |

-0.20 |

4% |

| 7 |

Sept. 2000 |

– | Mar. 2010 |

114 |

0.65 |

42% |

|

strongly positive-correlation periods (2, 4, 5, and 7) 42% of total months since Oct. 1917 49% of total months since Dec. 1929 |

||||||

.

Table 1 also shows that share prices have been strongly and positively correlated with current profits more than 40% of the time since 1917, and almost half the time since 1929. So the “exceptions” are not exceptional; the “rule” that share prices and current profits have become decoupled is no rule at all.

But B&N haven’t merely gotten their facts wrong. Because their facts are wrong, so is their paper’s key claim that we can infer that investors are gripped by “systemic fear” when the relationship between current profits and equity prices is strong and positive. They tell us that the two periods in which systemic fear prevailed were two periods of acute crisis, the Great Depression and the 2000s. If a strongly positive correlation between current profits and share prices were another exceptional feature of these periods of crisis, then the notion that we can infer the existence of systemic fear from the positive correlation might be plausible. But the 1930s and 2000s were not exceptional in that respect, as we have seen. And the other two strongly positive-correlation periods, which run from the early 1950s through the early 1970s, cannot plausibly be characterized as a time of systemic fear. On the contrary, that era was the so-called golden age of capitalism.[5] So a strongly positive correlation between current profits and equity prices does not allow us to infer the existence of systemic fear.

But the correlation data are B&N’s only evidence that capitalists were gripped by systemic fear in the 1930s and 2000s. (The statements by the Financial Times, Alan Greenspan, Bernie Sucher, Gillian Tett, and Mervyn King quoted in their paper discuss a highly uncertain environment, economic crisis, and discredited economic theory and ideology, not fear of the death of capitalism.) So they have not given us a good reason to accept that claim.

* * *

Nor do they give us a good reason to accept that the opposite of systemic fear–the conviction that capitalism is eternal–is the norm. Their “demonstrat[ion]” that capitalists are almost always guided by this conviction is fatally flawed. And since the same demonstration is the basis upon which B&N (2010, p. 3) claim that “[t]his … conviction is necessary for the existence of modern capitalism, at least in its present form,” they also fail to give us a good reason to accept this latter claim.

The most glaring flaw in their “demonstration” comes at the end, when they write, “the fact that capitalists invest shows that they expect … that the value of their assets will grow, not contract–and that expectation means that, consciously or not, they also think that the ritual that valuates their assets will never end” (Bichler and Nitzan 2010, pp. 3-4, emphasis added). The italicized clause is simply false. Just as some people buy lottery tickets even if they don’t expect to hit the jackpot, some people buy shares of stock even if they don’t expect their prices to rise. A large enough jackpot or a large enough potential capital gain more than makes up for a low probability of success. Hence, the fact that people invest does not mean that they normally expect capitalism to last forever.

Imagine, for instance, that you think that there’s only a 50-50 chance that capitalism will exist a year from now, and that you are considering buying shares of stock for $10,000 today. If capitalism doesn’t survive, you’ll lose the whole $10,000, so it would be better to spend the $10,000 now, not invest it. You believe that this outcome is as likely as not, but you also believe that if capitalism does survive, the shares will be worth $500,000 a year from now. If you are like most people, you’ll go ahead and invest.

Secondly, dozens upon dozens of experiments conducted by Nobel laureate Vernon Smith and colleagues (e.g. Smith, Suchanek, and Williams 1988; Porter and Smith 2003) during the past quarter century have demonstrated conclusively that people frequently invest in assets even when know that “capitalism” (i.e., its experimental equivalent) will soon perish. Participants in the experiments are given some cash and some shares of an imaginary equity. They are told that the shares will pay dividends for a fixed length of time, such as fifteen periods, and that the experiment will then end, at which point the shares will be worthless. The current fundamental value of a share–the sum of the average per-period dividends throughout the remainder of the experiment–is announced at the start of each period.[6] Participants can buy additional shares from other participants, sell their shares, or hold onto them and collect their dividends. At the end of the experiment, they get to keep their initial cash endowments, dividends, and any net capital gains they have obtained.

Now, B&N (2010, p. 3) claim to demonstrate that if capitalists believed that the system “would cease to exist at some future point,” then share prices “would have no-where to trend but down,” and capitalists would therefore be unwilling to buy additional shares. But even though participants in the experiments are absolutely certain that the system (i.e., the experiment) will soon cease to exist and that the asset’s fundamental value is continually falling, share prices typically rise throughout much or most of the experiment–big bubbles are formed–and the volume of investment in additional shares is typically heavy. This has been the routine outcome even when the participants in the experiments are over-the-counter stock dealers, businesspeople, or students at the California Institute of Technology or the Wharton School.

Research into why this “perverse” behavior occurs is still ongoing, but the basic reason why people buy shares that eventually become worthless, and whose prices must therefore eventually fall, is obvious. People think that they may well make a substantial profit in the meantime, by reselling the shares at prices higher than those they paid.

Finally, even if the rest of B&N’s “demonstration” were sound, it would not prove that capitalists are normally guided by the conviction that capitalism is eternal. At least it wouldn’t prove this if we use the word “conviction” in the normal way. B&N are undoubtedly aware that it would not, since they write that “consciously or not, [capitalists] also think that the ritual that valuates their assets will never end” (emphasis added). I doubt that “unconscious conviction” is a coherent concept, but even if it is, B&N’s appeal to it turns what started out as a provocative and straightforward claim into a piece of unfalsifiable Freudian speculation.[7]

.

References

Bichler, Shimshon and Jonathan Nitzan. 2010. Systemic Fear, Modern Finance and the Future of Capitalism, July. Available at bnarchives.yorku.ca/289/03/20100700_bn_systemic_fear_modern_finance_future_of_capitalism.pdf .

James, William. 1890. The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1. New York. Henry Holt and Co.

Nitzan, Jonathan and Shimson Bichler. 2009. Capital as Power: A study of order and creorder. London and New York: Routledge.

Porter, David P. and Vernon L. Smith. 2003. Stock Market Bubbles in the Laboratory, Journal of Behavioral Finance 4:1, 7-20.

Skidelsky, Robert. 2010. Keynes: The Return of the Master. London: Allen Lane.

Smith, Vernon L., Gerry L. Suchanek, and Arlington W. Williams. 1988. Bubbles, Crashes, and Endogenous Expectations in Experimental Spot Asset Markets, Econometrica 56:5, 1119-1151.

.

Notes

[1] They interpret a strong influence of current profits on share prices as evidence that investors are acting on the basis of the current situation, having abandoned their supposedly normal “conviction” that the shares will yield returns ad infinitum because capitalism is eternal.

[2] An internally inconsistent theory may happen by accident to hit upon correct conclusions, but the arguments it provides in support of these conclusions are always invalid.

[3] The correlation was negative between February 1961 and May 1964. If we count this as a distinct period and shorten periods 4 and 5 accordingly, the correlations during these periods increase to 0.92 and 0.82.

[4] I computed a correlation of 0.65 for period 7, while B&N report a correlation of 0.64. My other results match theirs, so this slight discrepancy may be due to a recent revision of the data set, published by Robert Schiller Shiller on his website.

[5] Since I, like B&N, computed the correlations between 3-year average values, periods 4 and 5 use data from August 1950 through December 1973, which is almost exactly coextensive with the golden age as defined by Skidelsky (2010, p. 24)–the period “from 1951 to 1973.”

[6] In some experiments, shares pay a fixed dividend. In others, participants are told what the possible dividends are and the probabilities that each will be paid.

[7] As William James (1890, p. 163, emphasis omitted) noted, “the distinction … between the unconscious and the conscious being of the mental state … is the sovereign means for believing what one likes in psychology and of turning what might become a science into a tumbling ground for whimsies.”

Be the first to comment