by Andrew Kliman

From what has been said so far, we can see that each individual capitalist, just like the totality of all capitalists in each individual sphere of production, participates in the exploitation of the entire working class by capital as a whole … in a direct economic sense, since … the average rate of profit depends on the level of exploitation of labour as a whole by capital as a whole. …

We thus have a mathematically exact demonstration of why the capitalists, no matter how little love is lost among them in their mutual competition, are nevertheless united by a real freemasonry vis-à-vis the working class as a whole. [Marx, Capital, vol. 3, pp. 298–300, emphasis added][1]

1. Introduction

Some months ago, I received an email message from a correspondent, who wrote:

I have recently read a paper titled “Phenomenology, Scientific Method and the Transformation Problem.”

In the paper, there are made the allegations that you cite chapters of Capital that do not support your arguments (on the MELT [monetary expression of labor-time], for example), among other things.

Does the paper properly present your arguments and the TSSI [temporal single-system interpretation]?[2]

He attached a PDF copy of the paper. It was written by Jesse Lopes and Chris Byron; it appeared in Historical Materialism, vol. 30, no. 1 (May 2022), pp. 209–236. I found that the paper misrepresented my arguments, disregarded or failed to understand the textual support I had provided for my interpretations, and seriously misunderstood the temporal single-system interpretation of the quantitative dimension of Marx’s value theory (TSSI). I reported and explained this in a reply to my correspondent and in a message to the authors; I received no response from the latter.

In the process of addressing my correspondent’s question, I read the whole paper. I found that its larger argument and representation of Marx’s views were also fundamentally flawed and riddled with serious errors.

This response to the paper reports what I found and justifies the conclusions I reached. I am publishing it for two reasons. First, by making my findings and conclusions public, the time I have spent engaging with the paper will no longer be time wasted. Second, by documenting the paper’s serious errors and misrepresentations, I am providing the evidence and arguments needed to support the request, which I hereby make, that the editors and publisher of Historical Materialism retract the paper. They are the ones who bear ultimate responsibility here. Anyone can have thoughts that are not ready for prime time. It takes a “scholarly” journal to turn such thoughts into a “scholarly contribution” that has been peer-reviewed and deemed worthy of publication.

Sections 2 through 5 of this response address the paper’s overall argument. Section 2 discusses Marx’s solution of the apparent contradiction between his value theory and real-world prices and profits, while Section 3 argues that Lopes and Byron (L&B) reject that solution. Section 4 discusses and responds to their central thesis: that value and price are incommensurable (lack a common measure) because price is something observable while value is not. Section 5 discusses their misrepresentation of Marx’s concept of cost-price. Section 6 responds to what they say about the TSSI and what I have written; the main issues here pertain to the MELT and the concept of a “single system” of value and price determination.

I fully expect that my request for retraction will be ignored or rejected by the editors and publisher of Historical Materialism. But even if they do retract the paper, that by itself will do nothing to solve the underlying problem. The present case is not an isolated exception. The underlying problem (and I speak from experience) is that searching for and getting the truth is not a central commitment of the journal in question or the milieu of which it is part. Caveat emptor.

But issuing this caveat will also do nothing by itself to solve the problem. There are far too many emptors who understand the situation well enough but find it in their interests to help publish this and similar journals, or to collaborate in other ways with them and the projects of which they are part. (Figuring out what those interests are is left as an exercise for the reader.) What is needed is thus a pro-truth movement of opposition from the left to break their haughty power.

I am well aware that some people think that critiques should limit themselves to criticizing ideas and refrain from criticizing others’ behavior. Given their position, such people should not criticize my behavior. I look forward to their refraining from doing so.

2. Marx’s Mathematical Solution

A main thesis of L&B’s paper is that “a mathematical solution to the transformation problem is a misapprehension of the relation between Marx’s abstract theory and concrete phenomena” (p. 209). To understand this assertion, we need first to understand what they mean by “the transformation problem.”

The term “transformation” refers to Marx’s account, in chapter 9 of Capital, volume 3, of the transformation of commodities’ values into prices of production. Marx’s critics have long alleged—falsely—that his account has been proven to be internally inconsistent.[3] When they speak of a “transformation problem,” they are generally referring to this supposed inconsistency in Marx’s account. L&B mean something different. The “transformation problem” to which they refer also pertains to chapter 9 of volume 3, but it is not the problem that allegedly plagues Marx’s account. It is the problem that he considered his account to have resolved, the “apparent contradiction” between his value theory and the prices and profits that exist in the real world.

According to Marx’s value theory, the magnitude of a commodity’s value is determined exclusively by the amount of labor that is socially necessary to produce it. In chapter 11 of Capital, volume 1 (pp. 420–421), he pointed out a key implication of the theory: the amounts of value and surplus-value (profit) that are created in capitalist production depend on the number of workers employed. Thus, the amounts of new value and surplus-value do not depend on the size of the total (constant plus variable) capital investment, but only on the size of the variable-capital component, since it is the portion of the total investment that is used to hire workers.

Yet this conclusion appears to contradict the fact that real-world profits—of individual firms and industries—do not vary in accordance with the numbers of workers employed. As Marx (Capital, vol. 1, p. 421) noted,

This law clearly contradicts all experience based on immediate appearances. Everyone knows that a cotton spinner [i.e., owner of a cotton-spinning factory], who, if we consider the percentage over the whole of his applied capital, employs much constant capital and little variable capital, does not, on account of this, pocket less profit or surplus-value than a baker [i.e., owner of a bakery], who sets in motion relatively much variable capital and little constant capital. For the solution of this apparent contradiction, many intermediate terms are still needed ….

L&B use the term “transformation problem” to refer to this apparent contradiction. “The problem is: how can surplus-value and profit be identical when enterprises which do not create much value profit just as much as enterprises that do create a lot of value?” (L&B, p. 227).[4] When they reject any and every “mathematical solution to the transformation problem,” on the grounds that such solutions “misapprehen[d] … the relation between Marx’s abstract theory and concrete phenomena” (L&B, p. 209), they are denying that the apparent contradiction can be resolved mathematically.

They intend to deny that Marx’s own solution was mathematical. Yet since his solution was indeed mathematical—and obviously and incontrovertibly so—they are also rejecting it along with every other “mathematical solution to the transformation problem.”

Below, I will consider the reasons why L&B reject mathematical solutions, and I will show that Marx’s own solution is among those they reject. Before doing so, however, it is important to provide the evidence needed to support my contention that Marx’s solution was obviously and incontrovertibly mathematical.

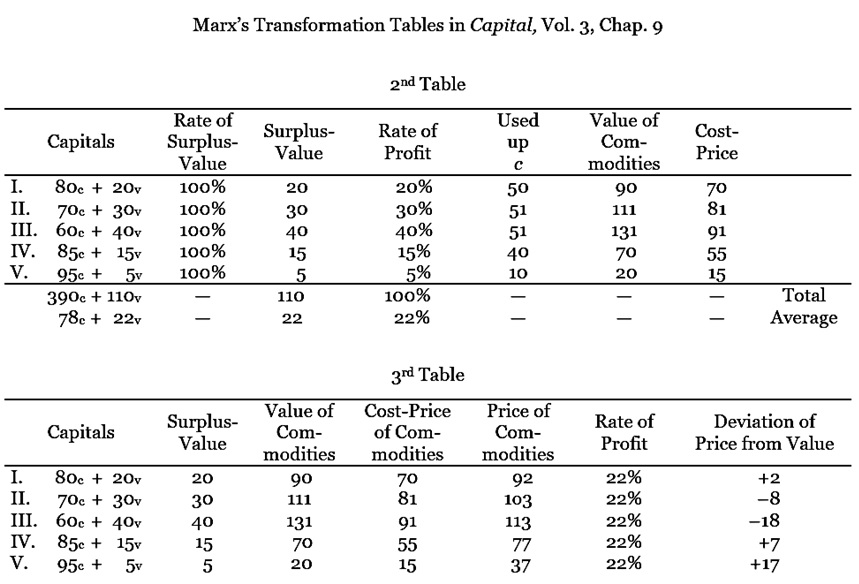

His solution is contained in the 2nd and 3rd Tables of chapter 9 of Capital, volume 3 (reproduced below) and the accompanying text.[5] The 3rd Table is clearly a continuation of the 2nd Table; its first four columns are carried over from it. The economy consists of five branches of production, I through V. The figures are those of a certain year (or other span of time). [6] The prices reported in the fifth column of the 3rd Table are what Marx calls “prices of production,” the hypothetical prices that branches would receive for their products if they obtained the average rate of profit.

In each branch, the value of the annual output (“Value of Commodities”) in the 2nd Table differs quantitatively from the annual output’s price of production (“Price of Commodities”) in the 3rd Table. Accordingly, the amount of surplus-value generated in the branch differs quantitatively from the amount of profit it receives. Each branch receives a profit of 22 (the difference between “Price of Commodities” and “Cost-Price of Commodities”). Thus, although Branch V “employs much constant capital and little variable capital,” it “does not, on account of this, pocket less profit” than Branch III, for example, which “sets in motion relatively much variable capital and little constant capital.” This is the apparent contradiction between Marx’s value theory and real-world prices and profits.

However, Marx (Capital, vol. 3, p. 257) called attention to the rightmost column of the 3rd Table. “Taken together, commodities are sold at 2 + 7 + 17 = 26 above their value, and 8 + 18 = 26 below their value, so that the divergences of price from value … cancel each other out.” Thus, “the sum of prices of production for the commodities produced in society as a whole—taking the totality of all branches of production—is equal to the sum of their values” (Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 259). Both sums equal 610. Accordingly, the sum of profits is equal to the sum of surplus-values, 110, and the two measures of the general (i.e., economy-wide) rate of profit—surplus-value divided by invested capital and profit divided by invested capital—both equal 22%.

This is Marx’s solution of the apparent contradiction. When one focuses on individual business firms or even whole branches of production, the prices and profits that exist in the real world appear to contradict the theory that commodities’ values are determined exclusively by the amount of labor needed to produce them. However, when one considers “society as a whole … the totality of all branches of production,” the real-world prices and profits do not necessarily contradict what the theory says about values and surplus-values. If the totals are like those of Marx’s example, then “the divergences … cancel each other out,” so that the theory holds true when it is understood as a theory pertaining to the aggregate economy.

This is clearly and undeniably a mathematical solution. There are numerical values for the branches’ values, surplus-values, prices, and profits. Marx subtracts the commodities’ values from the commodities’ prices to obtain deviations. He adds up the deviations and finds that they total zero. He adds up the values and the prices and finds that their totals are equal. The totals for surplus-value and profit are also equal. Throughout his argument, Marx reasons in terms of magnitudes, quantitative differences between magnitudes, and equality of magnitudes. Indeed, the equality of the aggregate-economy magnitudes is the crux of his solution, which he called a “mathematically exact demonstration” (see the epigraph at the start of this article)—the thing which confirms that real-world prices and profits do not necessarily contradict Marx’s value theory or his theory that the capitalist class’s exploitation of the working class is the exclusive source of its profit.

3. L&B’s Rejection of Marx’s Solution

That L&B reject Marx’s own solution becomes fully clear only at the end of their discussion of “how Marx solves the transformation problem” (L&B, p. 227). They characterize his solution as follows:

[W]hen the average rate of [sic] profit [is] added to the cost price[, this] gives the capitalist more profit than there is surplus-value created by the individual enterprise. In this case, surplus-value and profit are not identical. But this does not make any sense according to the theory because surplus-value and profit are identical. Therefore, they are both not identical and identical. This is a contradiction for the theory. The solution is of course that they really are identical in theory, but there is no way to prove this in appearance (a fortiori, no way to prove this in terms of price), beyond generally appealing to scientific method (as Marx does), which carves up inter-capital relations as appearances requiring an explanation via some invisible force (akin to gravity). Against this, the individual capitalist assumes quite reasonably that the average rate of profit fully and exhaustively explains profit above cost. But the capitalist is thereby trapped in appearances, merely redescribing concrete experiences. The only way to get around this is by appealing to an explanatory unobservable—value—the existence of which can only be inferred pending an analysis of phenomenal effects. [L&B, p. 228; underlined text emphasized in original; boldface emphasis added.]

L&B’s claim that Marx’s theory holds that surplus-value and profit are identical—not merely equal in the aggregate—is false. They provide no textual evidence to support the claim, and none exists. Provisionally, in the initial stages of his analysis in Capital, vol. 3, Marx did treat surplus-value and profit as if they were identical, but that is a different matter. In the theory as fully expounded, they are clearly not identical.

So why do L&B insist that surplus-value and profit are identical? I do not know for sure, but it may have something to do with their claim (which I will discuss presently) that value and surplus-value cannot be measured. If surplus-value cannot be measured, then Marx’s conclusion that total profit equals total surplus-value in the economy as a whole is obviously untrue and meaningless, and his solution to the apparent contradiction is therefore not a genuine solution. Thus, by claiming that surplus-value cannot be measured, L&B commit themselves, logically speaking, to rejecting Marx’s solution. Their insistence that surplus-value and profit are “identical in theory” may be a recognition of that commitment and a response to it. That is, it may be an attempt to come up with a solution that rejects the measurability of surplus-value, on which Marx’s own solution crucially depends, but that nonetheless sounds like his solution—to people who are not paying close enough attention, or who do not understand the difference between “identical” and “equal.”

According to L&B’s version of Marx’s solution, the task he faced in chapter 9 of volume 3 of Capital was to prove that surplus-value and profit “really are identical.” If that was what he needed to prove, then he of course failed and had to fail. No one can prove something that isn’t true, and it is not true that surplus-value and profit are identical. Marx’s solution of the apparent contradiction does not show that they are identical; it is premised on the fact that they are not. Indeed, they aren’t even equal in any branch of the economy; they are equal only at the level of the aggregate economy.

Another key implication of L&B’s version of Marx’s solution is that he failed to accomplish the actual task he set himself, the task of resolving the apparent contradiction between his theory and the facts. Although they insist that surplus-value and profit are identical, this does nothing to overcome the contradiction. As L&B concede, surplus-value and profit are only “identical in theory,” while “there is no way to prove [their identity] in appearance.” That is, there is no way to prove it on the basis of facts, because the facts simply contradict, and must contradict, (their version of) the theory. The apparent contradiction that Marx wished to resolve persists, unresolved, despite the supposed identity, and it must forever remain unresolvable.

What this implies, of course, is that (their version of) the theory is wrong and needs to be rejected. When an apparent contradiction between a theory and the facts has not yet been resolved, it is common in the sciences to stick with the theory in the meantime and to keep trying to resolve the apparent contradiction. But instances in which the contradiction cannot be resolved are another matter. If they cannot be resolved, the theory is wrong and must therefore be rejected. Refusal to reject it is dogmatism.

L&B refuse to reject (their version of) the theory. They defend this decision by dismissing the facts that contradict it as things that “essentially constitute ‘noise’ from the point of view of the abstract theory” (L&B, p. 227). This is a blatant misuse of the “noise” metaphor. The deviations between surplus-values and profits are not mere results of measurement error. They have nothing to do with modeling, so they cannot be attributed to modeling error. They are not random, but systematic and necessary, produced above all by the tendency for rates of profit to equalize. Given all this, it is simply wrong to dismiss the facts as “noise.”

At the end of the long paragraph quoted above, L&B seem also to defend their preference for theory over facts by holding out hope that some “analysis of phenomenal effects” will yet support (their version of) the theory. But “phenomenal effects” are facts. Thus, the most that L&B can hope for is that some new facts are uncovered that do not contradict the theory and that may seem to support it. But such facts would sit side-by-side with the recalcitrant fact that surplus-values and profits are always nonidentical and almost always unequal. This latter fact will not and cannot go away, all additional “phenomenal effects” notwithstanding. Thus, the contradiction between L&B’s version of Marx’s theory and the totality of facts persists and must persist. (Given the existence of at least one black swan, the theory that all swans are white is wrong, since no additional discoveries of white swans, no matter how numerous, can overcome the contradiction between the theory and the totality of facts.) Their version of Marx’s theory must therefore be rejected as contrary to fact, and refusal to reject it is dogmatism.

Marx famously excoriated the “vulgar economists’” privileging of appearances:

the vulgar economist thinks he has made a great discovery when, as against the revelation of the inner interconnection, he proudly claims that in appearance things look different. In fact, he boasts that he holds fast to appearance, and takes it for the ultimate. Why, then, have any science at all?

L&B are these vulgar economists’ (equally) evil twin:

the esoteric philosophers think they have made a great discovery when, as against the revelation of the inner interconnection between surplus-value and profit, they proudly claim that things are different in theory from how they look in appearance. In fact, they boast that they hold fast to theory, and take it for the ultimate. Why, then, have any science at all?

Science is not about holding fast to theory in the face of appearances (phenomena) that genuinely contradict it. That is dogmatism, not science. Science is about revealing “the inner interconnection” between theory and appearances. Among other things, this involves showing how the conclusions reached by theory do appear in the real world.[7] If they do not appear in some manner, then the theoretical conclusions must be rejected as contrary to fact. (In a very similar vein, Hegel stressed that “[t]he Essence must appear or shine forth“ (para. 131). A putative essence that does not appear in some manner is not an actually an essence.)

In chapter 9 of volume 3 of Capital, Marx revealed the inner interconnection between surplus-value and profit. He did so by showing that the appearances (facts) do not necessarily contradict his theory. There are, in fact, myriad deviations between the amounts of surplus-value that individual businesses and industries generate and the amounts of profit they receive. But Marx showed that this fact is completely compatible with his conclusion that the sum of profits in the economy as a whole is equal to the sum of surplus-values. The “law of value” of his value theory thus “appears or shines forth,” as a law pertaining to the aggregate economy.

Owing to their doctrine that value and surplus-value cannot be measured, L&B cannot make sense of this aggregate equality. They write that “the abstract quantities of value and surplus-value are part of the abstract theory of capital, which can never in reality be equal (gleich) to the quantities of transformed forms of concrete phenomena” (L&B, p. 217, emphasis added). They thus reject the inner interconnection between surplus-value and profit, and replace it with the claim that surplus-value and profit are identical. But this solves nothing. It fails to bridge the chasm between the theory and the facts—the apparent contradiction between them—since the alleged identity exists only in theory, not in fact. They thus force themselves into a dilemma from which they cannot escape: choose the facts or choose the theory. In other words, choose vulgar economics or choose dogmatism.

Marx did not confront that dilemma, because he did not deny that value and surplus-value are measurable. We need not confront it either.

4. The Measurability of Value

4.1. Appearances vs. Sense Perceptions

The central thesis of L&B’s paper is that value and surplus-value are not observable and, thus, not measurable, in contrast to prices and profits, which are measurable because they are observable. This thesis is the basis of their argument that the apparent contradiction that Marx undertook to resolve—between the values and surplus-values of his theory and the prices and profits of the real world—cannot be resolved mathematically.

Although L&B do not lay out their argument concisely, in one place, the core of the argument is basically that:

(1) Commodities’ values and surplus-value are essences or the “underlying reality” (L&B, p. 211 and passim), while prices and profits are appearances (phenomena).

(2) Specifically, values and surplus-values are not observable or otherwise perceptible by the senses, while prices and profits are perceptible entities.[8]

Therefore,

(3) Value and surplus value cannot be measured directly—only their effects in the “observable” world can be measured (L&B, p. 233)—while prices and profit can be measured directly.

Therefore,

(4) Value and price (and surplus-value and profit) are incommensurable (L&B, p. 217 and passim)—they lack a common measure—so it is impossible to compare them quantitatively.

Therefore,

(5) The apparent contradictions between values and prices, and surplus-values and profits, cannot be resolved mathematically (L&B, p. 209 and passim).

I wish to demonstrate that this argument fails and that its conclusions (3 through 5) are false. I believe that the initial premise (1) is correct and that it is an accurate interpretation of Marx’s view. But everything that follows it is false, including premise (2). The falsity of (2) is fatal to the entire argument, since it is its lynchpin; all of the argument’s conclusions depend crucially on (2).

L&B pass seamlessly between premises (1) and (2). They treat (2) as if it were a more specific way of expressing (1) and they construe Marx’s affirmations of (1) as affirmations of (2). But (1) and (2) are not the same thing, and (2) is neither implied by (1) nor a more specific way of expressing it. Prices and profits are indeed appearances, but they are not perceptible by the senses.

In what sense, then, are prices and profits appearances? How can something be an appearance if it isn’t perceptible by the senses? Marx provided the answer to these questions in the opening paragraph of volume 3 of Capital (p. 117). The aspect of his answer that is most relevant here is that prices and profits are forms of capital that “appear … in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production.” They appear to the mind, not to the senses. They are concepts, theoretical constructs. They arise in the course of doing business and in the course of trying to make sense of everyday life, and they are reinforced, refined, and systematized by ideologues, the media, and intellectuals.

Because concepts like price and profit are so familiar to us, and so useful in helping to reproduce the status quo—they generally “work” in practical contexts, they assist capitalists in their drive for boundless profit, and they do not challenge bourgeois ideology—it is easy to mistake them for physical things that our senses perceive. Conversely, because concepts like value and surplus-value are unfamiliar, not useful in business or daily life, and threatening to bourgeois ideology, they do not appear in everyday consciousness. So it is easy to mistake them for things that differ radically from prices and profits, above all by being fictions or “just theory.” In addition, businesses and statistical agencies collect, publish, and inundate us with massive amounts of estimated data on prices and profits, but produce no estimates of values and surplus-values. This further reinforces the illusion that we are dealing here with radically different kinds of things—even though both of them are sets of theoretical concepts that pertain to the same realities!

To illustrate the point, let us ask why capitalists seem to “see” profit but do not “see” surplus-value. L&B think the reason is that profit is—literally—observable while surplus-value is not. Marx was not under the same illusion. He attributed the difference to the capitalists’ economic and ideological interests. Because the amount of profit that a capitalist receives does not depend on the particular amounts of surplus labor and surplus-value that he extracts from the workers he exploits, these latter amounts are of no particular importance to him. He is a practical man, a businessman, and his business is not the business of explaining things and identifying their causes. So he does not search for a truthful explanation of where the profit he receives comes from. “He does not see it, he does not understand it, and it does not in fact interest him. … [Moreover,] he has here a particular interest in deceiving himself” (Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 268).

The core of L&B’s argument regarding appearances and measurability comes from Louis Althusser’s Reading Capital. Near the start of their paper (L&B, p. 211) they quote, approvingly, a statement in which Althusser talks about “bracket[ing] sensory appearances, i.e., in the domain of political economy, all the visible phenomena and practico-empirical concepts produced by the economic world (rent, interest, profit, etc.). … The effect of this bracketing is to unveil the hidden essence of the phenomena.” Later, L&B (p. 233) quote, again approvingly, the following statement of Althusser’s: “The fact that surplus-value is not a measurable reality arises from the fact that it is not a thing, but the concept of a relationship, the concept of an existing social structure of production, of an existence visible and measurable only in its ‘effects.’” On the next page, he wrote, “the ordinary economist may scrutinize economic ‘facts’: prices, exchanges, wages, profits, rents, etc., all those measurable facts, as much as he likes; he will [not] ‘see’ any structure at that level.”[9]

Thus, when L&B claim that prices and profits are measurable but value and surplus-value are not, they are following Althusser. And just as L&B wrongly conflate appearances and sense perceptions, so did Althusser, in the first sentence of the first quotation above. The “visible phenomena … produced by the economic world” are indeed “sensory appearances,” but “practico-empirical concepts” are certainly not. Neither they nor any other concepts are sense perceptions or objects perceived by the senses. Since prices and profits are among these “practico-empirical concepts” or, as Althusser also called them, “economic ‘facts,’” they are not sensory appearances.

Louis, Louis, oh no, you gotta go (yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah).

4.2. Non-Observability of Prices and Profits

In the context of L&B’s paper, the claim that prices and profits are entities perceived by the senses is ludicrous. The “transformation problem” that their paper discusses is about the relation between values and one particular kind of prices, prices of production, and the relation between surplus-values and one particular kind of profits, average profits. It is preposterous to claim that prices of production and average profits are observable or otherwise perceptible by our senses. They are hypothetical magnitudes. If the rate of profit that a business firm (or industry, etc.) obtained were equal to the average rate of profit in the economy as a whole, then the prices at which the firm would sell its products would be prices of production and the amount of profit it would receive would equal what Marx called the “average profit.” These are not the prices and profits we encounter in everyday life.

There may be cases in which actual prices equal prices of production and actual profits equal average profits, but if so, these cases are isolated flukes that have a zero probability of occurring. Furthermore, prices of production and average profits would not be perceived by the senses even in such cases. Perhaps accountants (how many, after working for how long?) could tell a firm that the profit it received was equal to the economy-wide average, but the senses cannot tell it that.

L&B (p. 224, emphases in original) contend that values are “one kind of thing” while prices are “another kind of thing.” It should be clear from the foregoing that this claim is seriously wrong. Prices of production and average profit are just like values and surplus-values in that they are theoretical constructs, generated by theorists in order to aid theorization. Moreover, prices of production are just like values in that they are no more likely to equal commodities’ actual prices than values are. Indeed, prices of production and values are so much alike that David Ricardo and his school failed to distinguish between the two concepts! (This failure is what created the discrepancy between theory and fact that Marx undertook to resolve.)

But what about the actual price of a commodity? Isn’t it perceptible by the senses? Numbers printed on price tags are observable, but they represent hoped-for prices, not actual ones. So imagine that what you observe, instead, is a bushel of wheat being exchanged for a certain amount of money. I do not wish to quibble; I will stipulate that you have observed its price. However, this is not what economists, those before Marx or those since Marx, mean by “the price” of wheat. What they do mean is a theoretical construct, not anything observable.

When one refers to “the price” of wheat, one abstracts from the fact that a bushel of wheat sells for different amounts of money in different locations.[10] It is possible to gather information on these amounts of money, compute their mean, and refer to the “average price of wheat.” This is already a theoretical construct of a sort, but since it is a generalization from actual observations, and I am not quibbling, I will stipulate that it is observable.

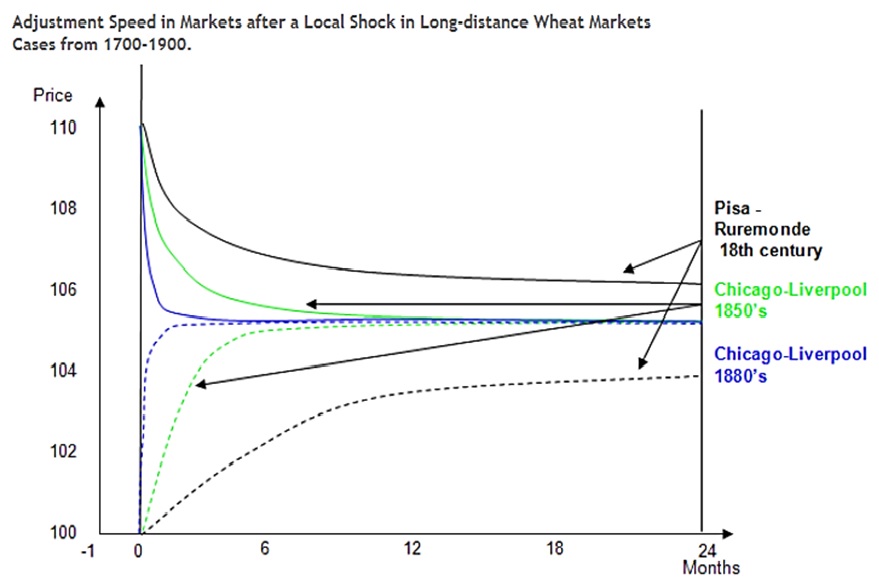

Now, in some contexts, when economists speak of “the price” of wheat, they may mean this average price. But this is not what they mean what they speak of it in theoretical contexts—and all of the main contexts in which Marx spoke of price were theoretical. What they do mean by “the price” of wheat is a specific hypothetical price—the price for which a bushel of wheat would sell if “the law of one price“ held true. This is a rather complex theoretical law. It presupposes “efficient” markets in which arbitrage reduces price differentials and leads to the elimination of all price differentials other than those attributable to transportation costs and transaction costs. The process of price adjustment can take a long time, if it takes place at all (see graph below). “The price of wheat” is the price that would exist, once the process of adjustment is completed, in the location where it is cheaper, or the price that would exist in the more expensive location minus transportation and transaction costs.

In sum, the prices (and thus the associated profits) of economic theory are theoretical constructs rather than objects of sense perception. In this respect, they are like values and surplus-values. Because these prices and profits are theoretical constructs, they cannot be measured directly. They are like values and surplus-values in this respect as well.

L&B’s contend that values and prices are radically unlike, incommensurable, and therefore that the “transformation problem” cannot be solved mathematically. These conclusions rest crucially on the idea that prices can be measured directly while values cannot. Since that idea is false, their argument is not a sound one; it needs to be rejected.

4.3 Commensurability of Values and Prices of Production

Of course, it is still possible in principle that someone may yet show that values and prices of production are indeed incommensurable. However, I think that is very unlikely. Here’s why.

When Marx compared the magnitudes of values and prices of production, and the magnitudes of surplus-values and profits, he was not comparing “an explanatory force” (L&B, p. 213) and data perceived by the senses. He was comparing two sets of theory-laden and theoretically generated data.[11] Furthermore, he was comparing amounts of one and the same thing, value. The prices of production and average profits are amounts of value, no less than the commodities’ values and surplus-value are, and the unit in which this value is measured is the same. (Were it not the same, the prices and the values could not be equal—nor could they be unequal. A joule of heat is not the same size as an elephant, nor is it larger or smaller.) [12]

Specifically, what Marx was comparing was two different distributions of value. Each is a distribution of the total amount of value created in the economy, the same total amount. The value of each branch’s output is equal to its cost-price plus surplus-value; the price of production of that output is equal to its cost-price plus average profit. All three components—cost-price, surplus-value, and average profit—are amounts of value. The cost-price component of the value is the cost-price component of the price of production. The surplus-values and the average profits are both amounts of surplus-value, portions of the total surplus-value created in the economy as a whole. The only difference between them is that the surplus-value component of the value is the actual amount of surplus-value created in the particular branch, while the average-profit component of the price of production is the amount of the total surplus-value that the branch would receive if its rate of profit were equal to the economy-wide average rate.[13]

How could this different distribution of value, one and the same amount of value, possibly turn value into un-value, “another kind of thing”? (L&B, p. 224, emphasis in original). What is involved here is strictly analogous to a situation in which you start with five groups of marbles, in each of which are some marbles marked CP and some marbles marked SV. You refrain from putting in or taking away marbles. You leave the CP marbles where they are. But you move some of the SV marbles from their group of origin into another group, and change the SV marbles’ markings to AP. This doesn’t turn marbles into un-marbles. So why is value any different? And how, exactly, does it become un-value?

5. L&B’s Misrepresentation of the Concept of Cost-Price

The concept of cost-price does not appear in volumes 1 and 2 of Capital, Marx introduced it at the start of volume 3. The following is L&B’s version of what he said:

Capitalists, we are told, conflate cost-price with the true price of a commodity because they are not consciously aware of the unpaid labour (the surplus-value) that enters into the actual price of their product. As a result, “the cost price of the commodity necessarily appears to [the capitalist] as the actual cost of the commodity itself.” [L&B, p. 211. The insertion in square brackets and the emphasis on “necessarily appears” are theirs; emphases in boldface added.]

Thus, according to L&B, Marx wrote that capitalists conflate a commodity’s cost-price with its actual price, failing to recognize that surplus-value also enters into the actual price.

Compare this to what Marx himself wrote (Capital, vol. 3, pp. 117–118; underlined text emphasized in original, emphases in boldface added):

The value of any commodity C produced in the capitalist manner can be depicted by the formula: C = c + v + s. If we subtract from the value of this product the surplus-value s, there remains a mere equivalent or replacement value in commodities for the capital value c + v laid out on the elements of production.

… This [latter] part of the value of the commodity, which replaces the price of the means of production consumed and the labour-power employed, simply replaces what the commodity cost the capitalist himself and is therefore the cost price of the commodity, as far as he is concerned.

What the commodity costs the capitalist, and what it actually does cost to produce it, are two completely different quantities. The portion of the commodity’s value that consists of surplus-value costs the capitalist nothing [… so] the cost price of the commodity necessarily appears to him as the actual cost of the commodity itself. If we call the cost price k, the formula C = c + v + s is transformed into the formula C = k + s, or commodity value = cost price + surplus-value.

… The capitalist cost of the commodity is measured by the expenditure of capital, whereas the actual cost of the commodity is measured by the expenditure of labour. The capitalist cost price of the commodity is thus quantitatively distinct from its value or its actual cost price; it is smaller than the commodity’s value, for since C = k + s, k = C – s. [Underlined text emphasized in original; emphases in boldface added]

Note that Marx refers, throughout this passage, to the value of the commodity. Its cost-price is a portion of this value. There is also another portion of this value—surplus-value. Thus, the commodity’s cost-price is “quantitatively distinct” from its value. To the capitalist, the cost-price appears to be the commodity’s actual cost. However, the actual cost of the commodity is its value, which is “measured by the expenditure of labour.”

Thus, contrary to what L&B assert, the passage says that:

- capitalists conflate a commodity’s cost-price with its value, not with its price;

- surplus-value is a part of the commodity’s value, not of its price;[14] and

- the commodity’s actual cost is its value, not its price.

In addition to transforming “value” into “price”(!), L&B’s version of the passage contains several misrepresentations by omission. They omit:

- all of Marx’s references to the commodity’s value;

- his statement that the commodity’s cost-price and its value differ quantitatively; and

- his statement that the commodity’s actual cost, its value, is measured by the expenditure of labor.

Were these errors of commission and omission inadvertent, or were they acts of deliberate falsification?

It is one thing to write “price” when one means “value.” It is another thing entirely to substitute “price” for “value” in a paper that is specifically and exclusively about the differences between them—and to do this twice in a single sentence.

The effect of each error, and of all of them collectively, is to make L&B’s arguments seem more plausible than they actually are. The omitted statement that commodities’ values are measured in terms of labor speaks loudly against their claim (which I will discuss in detail later) that “Marx … never states that labour-time is also a measure” (L&B, p. 230, emphases in original). When it is taken together with the other omitted statement, that cost-price and value are “quantitatively distinct,” it also implies that a “phenomenal” price magnitude, cost-price, can be quantitatively compared to a value magnitude and, indeed, to a value magnitude measured in terms of labor-time. This speaks loudly against L&B’s repeated claims that no such comparison is possible.

Indeed, the passage as a whole, as well as the very concept of cost-price, speak loudly against those claims. L&B (pp. 224–225, emphases in original) contend that the transformation that Marx discusses at the start of Capital, volume 3—the transformation of value into cost-price plus surplus-value—is a transformation “from one kind of thing to another kind of thing. This heterogeneity means there will not be an equality between value and price in terms of which a transformation problem can be mathematically solved.” This is preposterous. It is simply not true that the commodity’s value is “one kind” of thing while cost-price and surplus-value are “another kind” of thing. The cost-price is a part of the commodity’s value; the surplus-value is the other part of the commodity’s value. Both cost-price and surplus-value are themselves sums of value, and thus things of the same kind. Marx’s formula “commodity value = cost price + surplus-value” would be meaningless, not a genuine algebraic statement, if the terms (value, cost-price, and surplus-value) were not all things of the same kind.

L&B (p. 224) note that “Marx explicitly calls this transformation ‘qualitative.’” They think the word “qualitative” is very significant here. And it is—but for a reason opposite to the one they suppose. They are imagining that “qualitative” refers to profound transformation that alters the substance or essence of a thing, turning it into a completely different kind of thing with which it cannot be quantitatively compared. The transubstantiation of Catholic doctrine is a transformation of that type: the substances of bread and wine are (allegedly) transformed into the substances of the Body and Blood of Christ. Because the substances are altered, quantitative comparison is impossible. We cannot measure the alcoholic content of the Blood of Christ, or the number of cups of flour in the Body of Christ, because they do not contain alcohol or flour.

The transformation of value into cost-price plus surplus-value is completely different from that kind of transformation. It is not profound, but superficial (surface-level). It does not affect the essence of the thing. That is, it does not turn value into un-value. Cost-price and surplus-value are sums of value, just like the commodity’s total value. “Cost price plus profit” is a transformed form of value. (Although the term “form/s of value” appears five times in L&B’s paper (pp. 214, 216, 220, 223), they fail to understand its significance. The Body of Christ is not a form of bread, nor is the Blood of Christ a form of wine.) The transformation does not even alter the quantity of value: cost-price plus surplus-value is exactly equal to the commodity’s value. Thus, the transformation is only qualitative, merely qualitative.

Marx said this explicitly, in the passage from which L&B extract the word “qualitative.” He was commenting, later in Capital, volume 3, on two transformations discussed in the first chapter of the volume—the transformation of commodity value into cost-price plus surplus-value that we have been discussing, and a slight development from it, the transformation of commodity value into cost-price plus profit.[15] Marx (Capital, vol. 3, p. 267) wrote,

We saw in the first Part how surplus-value and profit were identical, seen from the point of view of their mass. … [There was no] difference in magnitude … between surplus-value and profit themselves. … [U]p to this point, the distinction between profit and surplus-value simply involved a qualitative change, a change of form, [without] any actual difference in magnitude.

Thus, the transformation of commodity value into cost-price plus profit is “simply … a qualitative change, a change of form.” “[U]p to this point”—that is, in chapter 1 of the third volume, in contrast to chapter 9 and subsequent chapters—there is no “difference in magnitude” between the commodity’s value and cost-price plus profit, nor between surplus-value and profit. If the essence, value, did not persist, unaffected, despite the transformation of its form, that would not be possible.

The first transformation, of commodity value into cost-price plus surplus-value, is merely a division of one whole into two parts. It is no different than the division of a collection of marbles into a red group and a blue group. In that case, too, the division is a mere “qualitative change, a change of form” that involves no “difference in magnitude.” The marbles, which originally appeared in the form of a single collection of red and blue marbles, now appear in the form of one collection of red marbles and a separate collection of blue marbles. But the marbles were things of the same kind before they were divided into groups, and they remain things of the same kind thereafter. Because, and only because, they remain things of the same kind, the statement “total number of marbles = number of red marbles + number of blue marbles” is meaningful. And because no quantitative change takes place—no marbles are added or subtracted when the marbles are divided into two groups—that statement is true.

6. Misunderstandings and Criticisms of the Temporal Single-System Interpretation

6.1. Two Distinctions between Value and Price

L&B (pp. 229–230, emphases in original) affirm that valuation in Marx’s theory is temporal, not simultaneous. They note that, when the labor-time socially necessary to produce commodities changes, Marx’s theory says that their values change, and that the revaluations “could entail discrepant input and output values” Thus, “[s]upporters of temporal valuation … are in agreement with Marx. Anyone that rejects temporal evaluation [sic] is misunderstanding Marx’s theory.” In addition, L&B (p. 229) claim to support the interpretation that values and prices in Marx’s theory constitute a single system, not two discordant systems: “Capital is about a single system,” not “a system of prices and another system of values.”

Yet L&B reject the temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI) of the quantitative dimension of Marx’s value theory, even though they supposedly support its twin components! The resolution of this apparent contradiction is simple. L&B actually do not support the single-system interpretation, because they do not understand what the term single system means.

In Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital” (pp. 24–25, emphases in original), I noted that

Marx distinguishes between price and value in two different ways. …

One distinction is between two ways of measuring value. Marx … holds that value has two measures, money and labor-time. …

The other distinction between “value” and “price” is quantitative. In this context, if we are speaking of a firm’s or industry’s output, “value” refers to the sum of value produced within a firm or industry—the value transferred plus the new value added—while “price” refers to the sum of value received by the firm or industry.

The terms single system and dual system refer (only) to the latter, quantitative, distinction between value and price. When introducing the terms in Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital” (p. 32, emphasis in original), I emphasized that “[t]he relevant distinction between values and prices here is the quantitative one.” Single-system interpretations say that the magnitudes of values and prices, although different, are both determined within one system of value determination. Dual-system interpretations say that there are two systems of value determination, one that determines only the magnitudes of values and another that determines only the magnitudes of prices.

L&B wrongly imagine, however, that the terms single system and dual system refer to the former distinction, between money and labor-time measures of value (and price). In their view, if there are two measures of value, then there are two “systems”—a “price” (i.e., money) system and a “value” (i.e., labor-time) system. This is just a misapplication of what the term system means in the present context. Single- and dual-system interpretations are about systems of value determination, but L&B are instead talking about “systems” of measurement. Furthermore, it is incorrect to identify price determination with monetary measurement, and value determination with labor-time measurement. The TSSI says that commodities’ prices and values are both measurable in terms of money and in terms of labor-time, and many if not most proponents of dual-system interpretations likewise recognize that values as well as prices are measurable in terms of money.

6.2. What Makes Marx a Single-System Theorist?

These confusions are the source of L&B’s charge that the TSSI is actually a dual-system interpretation. They claim that, “in identifying values with quantitative labour-times, Kliman [… is] referring us to a second system under the guise of a reduction. That is, [… he] quantif[ies] values, which gives us a ‘system’ of ‘values’” (L&B, p. 230).

No, it does not. The quantitative values and quantitative prices of Marx’s theory and the TSSI constitute a single system, not two discordant systems.[16] They constitute a single system when values and prices are measured in money terms, and when values and (labor-time equivalents of) prices are measured in terms of labor-time. I repeat: the distinction between single- and dual-system interpretations of Marx’s value theory has absolutely nothing to do with monetary versus labor-time measurement. It has to do with the quantitative determination of values and prices.

Both single- and dual-system interpretations say that the price of a firm’s or industry’s output generally differs (quantitatively) from the value of its output, and that the amount of profit that the firm or industry receives generally differs (quantitatively) from the amount of surplus-value generated within it. But while single-system interpretations say that there is a single (quantitative) amount of invested capital, as well as single (quantitative) amounts of the subcategories of capital (cost-price, constant capital, variable capital, etc.), dual-system interpretations and revisions of Marx’s theory say that “prices” of capital and its subcategories differ quantitatively from their “values.”

For example, single-system interpretations say that there is a single amount of total capital, the value of capital, the magnitude of which is determined by the prices of its material elements (means of production and labor-power).[17] In contrast, there are two different amounts of total capital in dual systems, the “price of capital,” the magnitude of which is determined by the prices of its material elements, and the “value of capital,” the magnitude of which is determined by the values of the material elements.

This dual determination of capital and its subcategories is what creates two systems of value and price determination that are wholly separate and discordant. The value of output and surplus-value are determined by the “value” of capital, while the price of output and profit are determined by the “price” of capital. Commodities’ prices become irrelevant to the quantitative determination of the “value” of capital, the value of output, and surplus-value. Commodities’ values become irrelevant to the determination of the “price” of capital, the price of output, and profit. In single-system interpretations, in contrast, the price of output and profit, as well as the value of output and surplus-value, are determined by the (single) value of capital, which in turn is determined by the prices of the capital’s material elements.

To understand this more clearly, consider once more the 2nd and 3rd Tables in chapter 9 of volume 3 of Capital reproduced above. They depict a single system of value and price determination.

In each of the branches of production, the value of output (“Value of Commodities”) in the 2nd Table differs quantitatively from the price of output (“Price of Commodities”) in the 3rd Table, and the amount of surplus-value generated in the branch differs quantitatively from the amount of profit it receives (which is not reported in the table, but which is 22 in all five cases, equal to the difference between “Price of Commodities” and “Cost-Price of Commodities”). However, the figures for the total capital invested in each branch (e.g., 80c + 20v) are identical in the 2nd and 3rd Tables. The figures for all subcategories of capital—constant capital (c), variable capital (v), “Used up c,” and “Cost-Price” (which is the sum of “Used-up c” and v)—are also identical.

Thus, the magnitudes of values and prices are both determined within one system of value determination. Both are determined by the branches’ cost-prices—a single set of cost-prices. (This contrasts with dual-system interpretations and revisions of Marx’s value theory, in which the values of outputs are determined by one set of “value” cost-prices, while the prices of outputs are determined by a (quantitively) different set of “price” cost-prices.) Since the value of output (“Value of Commodities”) equals cost-price plus surplus-value, while the price of output (“Price of Commodities”) equals cost-price plus profit, and each branch’s surplus-value differs (quantitatively) from its profit (= 22), the values and prices of Marx’s single system differ (quantitatively), even though they are determined by the same set of cost-prices.

The data in Marx’s example—the magnitudes with which it begins—are the figures for constant capital, used-up constant capital, variable capital, and the rates of surplus-value.[18] All other figures are derived from these data. On the basis of the same data, the TSSI derives the same results that Marx derived. No dual-system interpretation or revision does so.

6.3. Labor-time as the Immanent Measure of Commodities’ Values

L&B repeat their misunderstanding of what the terms single system and dual system mean when they write that, “according to Kliman, Marx seemingly does have two quantified systems.” Their evidence for this charge is my statement, quoted above, that “Marx … holds that value has two measures, money and labor-time.” I cited the first page of chapter 3 of Capital, volume 1 as evidence for this statement.

L&B (p. 230, emphases in original) challenge my interpretation, arguing that “[a]ll Marx claims in that section is that ‘money as a measure of value is the necessary form of appearance of the measure of value which is immanent in commodities, namely labour time’. Yet, he never states that labour-time is also a measure.”

Huh? Of course Marx states that labor-time is a measure. He states it in the sentence that L&B quote, right before they deny that Marx states it. Labor-time is “the measure of value which is immanent in commodities.” A fortiori, labor-time is a measure.

Marx (Capital, vol. 1, p. 677) reiterated this point in the sixth paragraph of chapter 19: “Labour is the substance, and the immanent measure of value, but it has no value itself.” And it should go without saying (but apparently it cannot) that Capital affirms, from the outset, in the first section of the entire work, that labor is a measure of value:

A use-value, or useful article, therefore, has value only because abstract human labour is objectified or materialized in it. How, then, is the magnitude of this value to be measured? By means of the quantity of the “value-forming substance”, the labour, contained in the article. This quantity is measured by its duration, and the labour-time is itself measured on the particular scale of hours, days[,] etc. [Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 129, emphasis added]

GREAT MOMENTS IN GASLIGHTING

L&B’s only “evidence” that Marx “never states that labour-time is also a measure” is the sentence in which he states that labor-time is the immanent measure of value. The other things they point to, the title of the first section of chapter 3 (“The Measure of Values”) and a few words of text on the same page, are about the fact that one of the several functions of money is to act as the measure of value. But that fact is not in dispute. It was standard economics in Marx’s time, and it remains so. What the singular (“the” measure instead of “a” measure) means in this context is simply that money, not “t-shirts, bicycles, or corn” instead of or in addition to money, is “the device we use to measure value in economic transactions … a common measure of value across the economy.” The singular “the” distinguishes money from other commodities, not from labor-time. Thus, in using the singular, Marx was reflecting common usage and common practice, not denying that labor-time is “the measure of value which is immanent in commodities.”

Consider the alternative: that Marx did intend to deny that labor-time is a measure of value. He would then be guilty of self-contradiction. The section title on the first page of chapter 3 would deny, but the text on that page would affirm, that labor-time is “the measure of value which is immanent in commodities.” Since this potential inconsistency is avoidable—by embracing my interpretation—a standard principle of interpretation says that the interpretation that creates the inconsistency, L&B’s interpretation, should be rejected (see chapter 4 of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency.)

Of course, money and labor-time are different kinds of measures of value. Money appears as a measure of value “on the surface of society” (Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 117), while labor-time does not. Prior to Marx, labor-time appeared as a measure of value only in the works of Ricardo and other classical political economists, where it was used to explain changes in the rates at which commodities exchange. This difference has nothing to do with money being observable while labor-time is unobservable (if anything, the opposite is true), nor anything to do with what L&B seem to be suggesting here, namely that the supposed difference in observability makes money able to serve as a measure of value while labor-time is unable. It has nothing to do with these things because money is not observable.

I have four words for anyone who imagines otherwise: show me the money! You cannot. You can show me clusters of pixels on a computer screen, colored paper rectangles, and small round pieces of metal, but not money. It is a concept, not a physical thing. It appears on the surface of society because it is “in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production” (Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 117), not because it is perceived by the senses.

6.4. Marx’s Comparison of Labor-Time and Monetary Measures of Value

L&B (p. 231) go on to say that

Kliman does provide another citation to support his view. He says that Marx “sometimes measures [values] in terms of labour-time, and occasionally he compares the two” [labour-time and monetary measures of value]. We have referenced that page numerous times, and the reader is asked to examine it carefully, because we have no idea what Kliman is talking about. Based on textual evidence alone we believe Kliman is imposing labour-time as a measure. [First insertion in square brackets is L&B’s; the second one is added.]

On the page of Capital I cited, Marx wrote that commodities’ prices of production can change because the general rate of profit changes. But changes in the latter almost always take long time, so

[i]n all periods shorter than this, therefore, and even then leaving aside fluctuations in market prices, a change in prices of production is always to be explained prima facie by an actual change in commodity values, i.e. by a change in the total sum of labour-time needed to produce the commodities. We are not referring here, of course, to a mere change in the monetary expression of these values. [Bloßer Wechsel im Geldausdruck derselben Werte kommt hier selbstredend gar nicht in Betracht: Mere changes in the money-expression of the same values are, naturally, not at all considered here.] [Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p.266]

This statement compares actual changes in commodities’ values to changes in their monetary expression (i.e., changes in values measured in terms of money). The actual changes are defined as changes in the amount of labor-time needed to produce the commodities. So the commodities’ actual values are implicitly defined—in this particular context—as those amounts of labor-time (“changes in Y are changes in X” implies “Y are X”). In short, Marx is comparing values measured in terms of labor-time and values measured in terms of money. Changes in values measured in terms of labor-time are almost always the cause of short-term changes in prices of production, while changes in values measured in terms of money “are, naturally, not at all considered here.”[19]

Thus, based on textual evidence alone, Marx compared labour-time and monetary measures of value on the page that L&B referenced numerous times. The reason they “have no idea what Kliman is talking about” seems to be that they have no idea what Marx was talking about.

6.5. Marx’s Conversion of Labor-Time Magnitudes into Monetary Magnitudes

L&B (p. 231) also argue that Marx did not convert quantities of labor-time into equivalent quantities of money or vice-versa:

Kliman … provide[s] mathematical conversion tables to “measure value and price in the same units” utilising a “conversion factor” dubbed MELT (The Monetary Expression of Labour Time). We believe that MELT has no basis in Marx’s work, despite … claims to the contrary.

Kliman argues that Marx “frequently employed such a [conversion] factor” and cites Part 2 of Chapter 7 of Capital Volume I. No such conversion factor exists in that chapter …. To be blunt, the chapter has absolutely nothing to do with “employing” some “conversion factor.” [Insertion of “conversion” in square brackets is L&B’s.]

Of course, Marx did not use the term “monetary expression of labor-time,” and he generally did not explicitly state its numerical value. But he did employ it throughout the second section of chapter 7; it does exist there. More importantly, his employment of the MELT is absolutely crucial to the chapter. The “secret of profit-making“ (Marx, Capital, vol. 1, p. 280), revealed in the chapter’s second section, is revealed by means of the MELT, and it could not have been revealed without it.

In the passages from the second section of chapter 7 quoted below, boldfaced text shows that many of Marx’s numerical results follow from his employment of a MELT that is equal to one-half shilling per labor-hour (½ s/hr). His example assumes that the workday is 12 hours’ long. All insertions in square brackets are mine.

For spinning [10 lb. of] yarn, raw material is required; suppose in this case 10 lb. of cotton. … our capitalist has, we will assume, bought it at its full value, say 10 shillings. … We will further assume that the wear and tear of the spindle, which for our present purpose may represent all other instruments of labour employed, amounts to the value of 2 shillings. If then, twenty-four hours of labour, or two working days, are required to produce the quantity of gold represented by 12 shillings [12 s = (½ s/hr) ∙ 24 hrs], it follows first of all that two days of labour [= 24 hours] are objectified in the yarn [24 hrs = 12 s / (½ s/hr)]. …

We now know what part of the value of the yarn is formed by … the cotton and the spindle. It is 12 shillings, i.e. the materialization of two days of labour [12 s = (½ s/hr) ∙ 24 hrs]. The next point to be considered is what part of the value of the yarn is added to the cotton by the labour of the spinner. …

We assume that spinning is simple labour, the average labour of a given society. Later it will be seen that the contrary assumption would make no difference. …

We assumed, on the occasion of its sale, that the value of a day’s labour-power was 3 shillings, and that 6 hours of labour was incorporated in that sum [6 hrs = 3 s / (½ s/hr)] …. [I]n 6 hours [the worker] will convert 10 lb. of cotton into 10 lb. of yarn. Hence, during the spinning process, the cotton absorbs 6 hours of labour. The same quantity of labour is also embodied in a piece of gold of the value of 3 shillings [6 hrs = 3 s / (½ s/hr)]. A value of 3 shillings, therefore, is added to the cotton by the labour of spinning. [3 s = (½ s/hr) ∙ 6 hrs].

Let us now consider the total value of the product, the 10 lb. of yarn. Two and a half days of labour [= 30 hours] have been objectified in it. Out of this, two days [= 24 hours] were contained in the cotton and the worn-down portion of the spindle, and half a day [= 6 hours] was absorbed during the process of spinning. This two and a half days of labour [= 30 hours] is represented by a piece of gold of the value of 15 shillings [15 s = (½ s/hr) ∙ 30 hrs]. Hence, 15 shillings is an adequate price for the 10 lb. of yarn, and the price of 1 lb. is 1s. 6d. [= 1.5 shillings]. …

The worker therefore finds, in the workshop, the means of production necessary for working not just 6 but 12 hours. … now 20 lb. of cotton will absorb 12 hours’ labour and be changed into 20 lb. of yarn. … Now five days [= 60 hours] of labour are objectified in this 20 lb. of yarn; four days [= 48 hours] are due to the cotton and the lost steel of the spindle [48 hrs = (12 s + 12 s) / (½ s/hr)], the remaining day has been absorbed by the cotton during the spinning process. Expressed in gold, the labour of five days [= 60 hours] is thirty shillings [30 s = (½ s/hr) ∙ 60 hrs]. This is therefore the price of the 20 lb. of yarn, giving, as before, 1s. 6d. [= 1.5 shillings] as the price of 1 lb. But the sum of the values of the commodities thrown into the process amounts to 27 shillings. The value of the yarn is 30 shillings. Therefore … 27 shillings have been transformed into 30 shillings; a surplus-value of 3 shillings has been precipitated. [Capital, vo1. 1, pp. 293–301]

These passages show incontrovertibly that Marx revealed the secret of profit-making by employing the MELT.

Yet I claimed more than that above. I claimed that the secret of profit-making could not have been revealed without employing the MELT. To demonstrate this fact, consider how the last sentence of the first paragraph I quoted would read in the absence of the MELT:

If, then, twenty-four hours of labour, or two working days, are required to produce the quantity of gold represented by 12 shillings, it follows first of all that … bupkis. Presumably, the fact that the used-up means of production are worth 12 shillings has something to do with labour. But exactly what, and exactly how much labour, I have no idea, because value cannot be measured in terms of labour-time.

And as Parmenides taught, from bupkis comes bupkis. The end of the final paragraph would thus read:

the sum of the values of the commodities thrown into the process amounts to 27 shillings. Presumably, the value of the yarn has something to do with the labour that produced it. But exactly what, and exactly what the value of the yarn is, I have no idea, because value cannot be measured in terms of labour-time. Therefore … bupkis.

6.6. The Law of the Tendential Bupkis in the Rate of Bupkis

L&B (p. 232) then write, “If Marx ‘frequently’ used such a conversion factor as MELT, why is only one inaccurate citation provided [by Kliman]?” I trust that disinterested readers will recognize that the charge of inaccuracy has been demolished by the evidence and argument presented above. As for the question about why I provided only one citation, the answer is that I didn’t feel the need to belabor the obvious. But I was evidently wrong about that. So here is another citation, from the start of Marx’s presentation of the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit:

Say that £100 provides the wages of 100 workers for one week. If these 100 workers perform as much surplus labour as necessary labour, they work as much time for the capitalist each day, for the production of surplus-value, as they do for themselves, for the reproduction of their wages, and their total value product would then be £200, the surplus-value they produce amounting to £100. [Marx, Capital, vol. 3, p. 317]

Here, Marx employed a MELT equal to £2 per labor-week to compute the total value product and the surplus-value. He could not have obtained the results, £200 and £100 respectively, without it.[20] Consequently, he could not have divided the surplus-value of £100 by a series of ever-larger capital investments, and thus he could not have shown that the result of this division is a series of rates of profit that declines as capital investment increases in relation to employment of living labor. In short, he could not have derived the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit.

This is the actual series that Marx (Capital, vol. 3, p. 317) computed. c stands for constant capital, v for variable capital, and p’ for the rate of profit:

if c = 50 and v = 100, then p’ = 100/150 = 66 2/3 per cent;

if c = 100 and v = 100, then p’ = 100/200 = 50 per cent;

if c = 200 and v = 100, then p’ = 100/300 = 33 1/3 per cent;

if c = 300 and v = 100, then p’ = 100/400 = 25 per cent;

if c = 400 and v = 100, then p’ = 100/500 = 20 per cent.

The law that Marx (Capital, vol. 3, p. 318) derived from this series is that “this gradual growth in the constant capital, in relation to the variable, must necessarily result in a gradual fall in the general rate of profit, given that the rate of surplus-value … remains the same.”

Yet if had not employed the MELT, the series would have been:

if c = 50 and v = 100, then p’ = bupkis/150 = bupkis;

if c = 100 and v = 100, then p’ = bupkis/200 = bupkis;

if c = 200 and v = 100, then p’ = bupkis/300 = bupkis;

if c = 300 and v = 100, then p’ = bupkis/400 = bupkis;

if c = 400 and v = 100, then p’ = bupkis/500 = bupkis.

and the “law” derived from it would have been: “this gradual growth in the constant capital, in relation to the variable, must necessarily result in … bupkis.”

6.7. Marx’s Two Rates of Profit

Immediately after their “one inaccurate citation” charge, L&B (p. 232) reveal their complete confusion regarding differences between price and value magnitudes. They mix and match and make a hash out of different units of measurement, on the one hand, and quantitative differences on the other, writing that

Kliman also argues that once one accepts MELT, and Marx’s usage of these conversion factors, we can see that Marx also has “implicit in his work a second rate of profit,” giving us the “value rate of profit” and the “price rate of profit.” How is this not two systems?

In the first place, I never suggested that one needs to “accept” the MELT to recognize that there are two rates of profit implicit in Marx’s work. The MELT is relevant to the measurement of value. By means of the MELT, variables measured in terms of labor-time are converted into variables measured in terms of money, and vice-versa. But the MELT is not relevant to the existence of two rates of profit in Marx’s work, or to the difference between them, because that difference is quantitative.

On the page of Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital” that L&B cite, I wrote that “[Marx’s] theory recognizes that price and value can differ quantitatively, and therefore that the amount of profit a firm or industry receives can differ from the amount of surplus-value it produces.” Hence, in addition to the “value” rate of profit, which is surplus-value divided by total capital advanced, “there is also implicit in his work a second rate of profit,” the “price” rate of profit, which is profit divided by total capital advanced (p. 26, emphases added). I don’t know how I could have been clearer. The amount of profit differs quantitively from the amount of surplus-value, and thus the “price” rate of profit differs quantitatively from the “value” rate of profit.

A profit of £100 does not differ quantitatively from a surplus-value of 49 labor-weeks; neither of these is greater than the other, nor are they equal. They cannot be compared quantitatively. The magnitudes of profit and surplus-value can be compared only when they are measured in the same unit. In other words, they can be compared only when the MELT no longer plays a role, because an amount of surplus labor has already been converted into an amount of surplus-value measured in terms of money, or an amount of profit measured in terms of money has already been converted into its labor-time equivalent, by means of the MELT.

Secondly, to “see that Marx also has ‘implicit in his work a second rate of profit,’” one only needs to look at the 2nd and 3rd Tables of chapter 9 of Capital, volume 3. Since L&B’s article (pp. 218ff) discussed these tables at some length, the evidence was right before their eyes. The “value” rates of profit are reported in the fourth column of the 2nd Table; the “price” rates of profit are reported in the sixth column of the 3rd Table.

Don’t know much about optometry. Don’t know much phenomenology. But I do know one and one is two.

These two rates of profit are the rates of profit of the same set of branches of production, I through V. Yet each branch’s “value” rate of profit differs—quantitatively—from its “price” rate of profit. The five branches’ “value” and “price” rate of profit are, respectively, 20% and 22%, 30% and 22%, 40% and 22%, 15% and 22%, and 5% and 22%.

Finally, the answer to L&B’s question, “How is this not two systems?,” was given above, in subsections 6.1 and 6.2. The magnitudes of surplus-value and profit, although different, are both determined within one system of value determination. There is a single amount of total capital invested in each branch, reported in the first columns of the 2nd and 3rd Tables. Marx uses this single set of figures for capital and its subcategories to derive both value magnitudes and price magnitudes (e.g., “Value of Commodities” and “Price of Commodities”). And because he uses a single set of figures, not one set of “value of capital” figures and a quantitatively different set of “price of capital” figures, the result is one system of value and price determination, not two wholly separate and discordant systems.

By severing value and price determination into separate systems, dual-system interpretations and revisions of Marx’s value theory create a quantitative discrepancy between the aggregate (economy-wide) “price” and “value” rates of profit. What causes these rates of profit to be unequal—even when aggregate profit equals aggregate surplus-value—is the dualistic determination of the magnitude of invested capital. Aggregate profit divided by the aggregate “price of capital” (i.e., the “price” rate of profit) does not equal aggregate surplus-value divided by the aggregate “value of capital” (i.e., the “value” rate of profit) because the two sums of capital differ quantitatively. In Marx’s work and in the TSSI, however, there is a single amount of aggregate capital, so the aggregate “price” rate of profit does equal the aggregate “value” rate. In Marx’s 2nd and 3rd Tables, aggregate profit and aggregate surplus-value both equal 110, the single amount of aggregate capital is 390c + 110v = 500, and so both aggregate rates of profit equal 110/500 = 22%.

Notes

[1] Here and throughout, I cite and quote from the Penguin editions of volumes 1 and 3 of Capital, while the links are to online versions of these works that are translated differently.

[2] Personal correspondence, July 24, 2002, author’s name withheld.

[3] See Andrew Kliman, Reclaiming Marx’s “Capital”: A Refutation of the Myth of Inconsistency, especially chaps. 8 and 9.

[4] I quote this statement to show how L&B employ the term “transformation problem,” not to endorse their statement. Below, I will discuss their claim that Marx’s theory says that surplus-value and profit are “identical.”

[5] Marx (Capital, vol. 3, p. 255) set aside his 1st Table because it overlooked the distinction between fixed and circulating capital and could thus lead to “totally incorrect conclusions” (Marx, p. 255).

[6] c and v denote constant capital and variable capital, respectively. Surplus-value equals variable capital times the rate of surplus-value. Each branch’s cost-price is the sum of its variable capital and the portion of its constant capital that is used up during the year’s production (“Used up c”). The value of each branch’s annual output (“Value of Commodities”) equals the cost-price plus the surplus-value; the price of its annual output (“Price of Commodities”) equals the cost-price plus profit. The amount of profit received (not reported in the 3rd Table) is 22 in each branch. In the 2nd Table, a branch’s rate of profit equals its surplus-value divided by its total (constant plus variable) capital; in the 3rd Table, its rate of profit equals its profit divided by its total capital. As I shall discuss later, these two rates of profit are frequently called the “value” and “price” rates of profit, respectively.

[7] In the same letter from which I have just quoted, Marx wrote, “Science consists precisely in demonstrating how the law of value asserts itself” (emphasis in original).

[8] See esp. p. 223, where L&B claim that prices have been “observed for millennia,” and the following statement on p. 213 (emphases in original): “‘the transformation problem’ … arises, precisely because value is treated in the manner of price as a phenomenal-level datum. But value is precisely not a phenomenal-level datum—it is … an abstract origin intended to explain and unify various phenomenal-level appearances of prices, and prices are data. Value is not a datum but an explanatory force irreducible to data.”