by Theresa Henry

The Iranian masses, led by women and youth, continue to demand the fall of the Islamic Republic (see our October 2022 report). The protests continued this month, under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom,” despite escalating state violence that includes shooting at protesters and public executions.

Anti-regime strikes and protests across Iran were sparked by the murder of a young Kurdish woman Jina (Masha) Amini on September 16, while she was in the custody of the “Morality Police.” The protests’ continuation into the new year reflects the protesters’ enormous courage, as well as deepening grassroots organization.

As the protests continue, the regime has intensified its repression in the form of forced confessions, sexual assault of protesters, and other torture, including torture of children. The staggering figure of 522 protesters have been killed since September, according to Human Rights Activists in Iran’s “Daily Update,” which contains much information about the fate of those arrested as well.

At the same time, workers in oil and gas and other industries struck against their conditions during December.

The mass movement is developing at a “miss-it-if-you-blink” pace, and not all information on the rebellion is available in English, so it is often hard to understand exactly what is going on. This is made even harder by journalistic blunders such as the New York Times publishing a “PR diversion” of the Iranian regime which led many to falsely believe that it was about to abolish the infamous “Morality Police.”

Such mistakes aid the Islamic Republic’s campaign of misinformation and remind us that it is of the utmost importance to focus on the voices and actions of the Iranian masses themselves. This article aims to do just that by showing that even the regime’s most inhumane forms of repression have not been enough to stop the Iranian masses’ remarkable struggle for freedom.

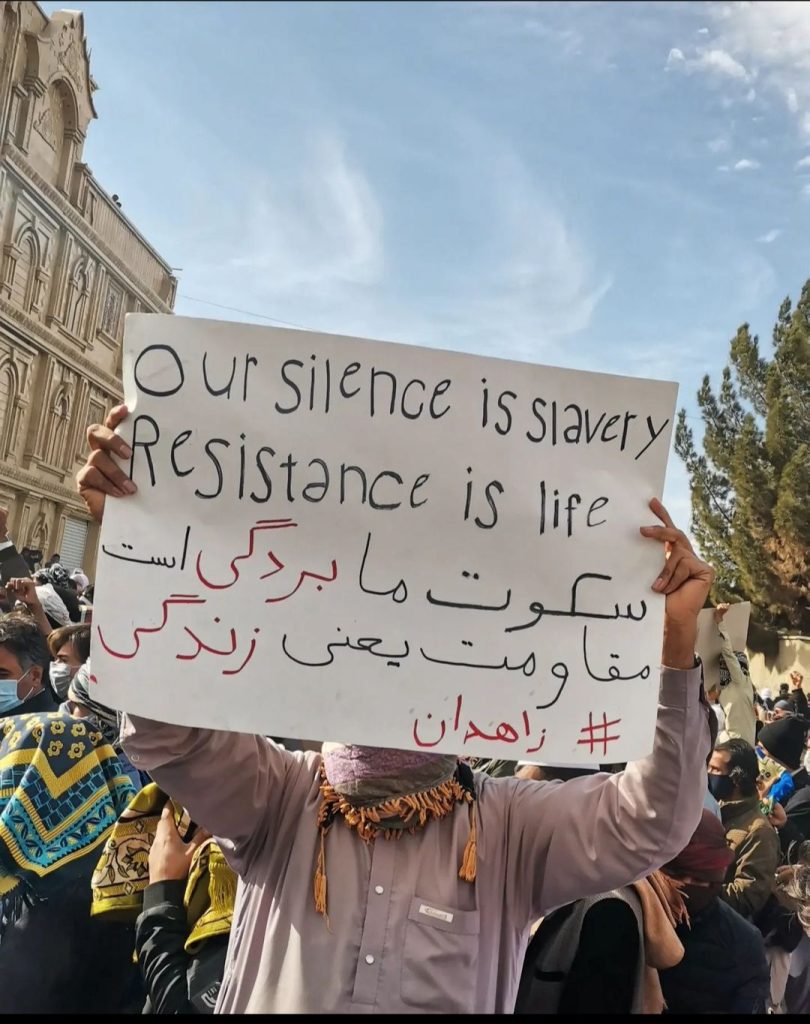

Protester in Zahedan holding a sign reading “our silence is slavery, resistance is life.” Credit: Iran Instagram page.

Death Sentences Begin, Arrests and Killings Continue

In response to the continued strikes and protests, the Islamic regime has turned to increasingly more extreme methods to put down the movement. It began sentencing Iranians to death and carrying out their executions in December. Iran International states that executions doubled in 2022 and that those executed include underage protesters. Rather than this development slowing down the movement, though, if has led to even more anger and protests.

Among those sentenced to death by the regime are soccer player Amir Nasr-Azadani, radiologist Hamid Ghara-Hasanlu, and at least 11 other men. The regime has already executed Moshen Shekari and Majidreza Rahnavard, two 23-year old men involved in the protests. Rahnavard was stabbed to death by the Basij Resistance Force division of the “Morality Police” and then hanged in public.

The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) describes how the Islamic regime targets athletes who have voiced support for the protests and how it is using the death sentences and executions to stifle dissent. Furthermore, CHRI states that “all of the 11 individuals who are currently on death row were convicted after sham trials in which they were denied due process, including a lawyer of their choice.” 22 death sentences have been issued to date.

As From Iran, a radical, independent feminist organization, reminds us: “these are not just numbers, they are real people who had real lives.” On its Instagram page, From Iran began a series of dispatches entitled “Diary From: A Revolution.” The sixth issue posted on December 21 includes a reflection from Leily Mahdavi. Recalling her visit to the morgue to identify her son, 16-year old Siavash Mahmoudi, who died during a protest in Tehran, she addresses her dead son: “the longest night for me is September 21, the cursed night I had to wait until morning for them to show you to me.” Mahdavi’s pain is shared by the loved ones of the 522 protesters who have been murdered by the regime.

On top of the death sentences and executions, the Islamic regime has carried out mass arrests and abductions of children in the Kurdish region. Among those arrested were a French national and a Belgian national, for “espionage,” filmmakers, Iranian actress Taraneh Alidoosti, researcher Saeed Madani, dissident cleric Vahid Heroabadi, and thousands of students, protesters, and activists.

It appears that the regime will stop at nothing to put an end to the uprising. There are reports of the Revolutionary Guard shooting at women’s genitals. In addition to those jailed and hanged, some are simply shot as they protest. One such instance was 29-year old Mehran Basir Tawana, who was shot in the back of the head, execution style, in Northern Iran. Yet, the Islamic Republic’s inhumane repression has failed to crush the movement.

Workers Strike Against the Regime

Iranian oil workers started off the new year by going on strike January 3 to protest their poor living conditions. According to Free Them Now, an international solidarity group of trade unionists, the workers refused to send in their production reports, which are “vital for production” in the industry. The spread of strikes in the oil industry has “created the ground for nationwide strikes, which are discussed among the workers.” These strikes complement the anti-state protests because disruptions in the oil and gas sector, the major source of the Islamic Republic’s revenue, are key to bringing down the regime.

The January oil worker strikes followed nationwide strikes, starting on December 18, that included oil workers, firefighters, cement workers, and truck drivers. These workers were protesting poor living conditions in addition to “discriminations, high job risks and lack of any safety in the work environment,” as well as low wages. During the December job actions, the “organizing council of oil contract workers” called on “all workers to strike and protest against the executions and arrests by the Islamic regime,” weaving the economic actions into the broad social movement.

Furthermore, on December 6 workers were on strike in “several major industries” such as steel, petrochemical, transportation, and cement. Free Them Now notes that the “Coordinating Council of Cultural Trade Union Organizations,” which organizes teachers in Iran, voiced support of the three-day strikes and protests that took place between December 5 and 7. One Twitter user posted that the strike on December 5 was the largest strike that has taken place in opposition to the regime in this wave of protests.

Workers began strikes at the end of November. At the time, CHRI stated that “the fact that so many workers are striking, even while labor leaders are amongst the thousands who’ve been arrested since September, speaks to the level of discontent against the government.” On top of mobilizing against the “government’s lack of response to the problems” facing the working class, the striking workers were motivated by the “plight of our innocent colleagues and other people in Kurdistan, Baluchistan, and Izeh and other blood-stained cities.” In other words, the strikes speak both to general discontent against the government and to solidarity across ethnic and cultural divides in Iran.

Grassroots Organization Deepens

Another encouraging dimension of the rebellion is the formation and deepening of grassroots organizations. On December 15, a “group of labor and civil organizations” released a collective statement on the demands of the revolution: “Woman, Life, Freedom.” The statement outlines their demands for each of the three dimensions of the revolution and concludes by saying that “Woman, Life, Freedom is the antithesis of Iran’s capitalist, patriarchal, and theocratic system.” The statement reveals one tendency within the movement that strives for a secular reorganization of Iranian society and an environmentally friendly, social democratic reorganization of the economy.

One grassroots group, the Red Revolutionary Youth Committee of Mahabad, also released a statement in December in solidarity with rape survivors. The statement points out that Iran’s “traditional” or conservative-religious communities treat rape survivors as transgressors within the community and that therefore survivors face shame, humiliation, harassment, and death. In response to the reports of the regime abducting women and girls, the Youth Committee of Mahabad is calling on “all women and men seeking freedom and equality to support rape survivors in the healing process, by forming grassroots associations and collectives and to oppose reactionary, fundamentalist beliefs in society.”

On December 15, Iran International released an article showing that the protest led to the formation of youth groups involved in sabotage. These groups are modeled after the anti-fascist “Churchill Clubs” that arose during World War II. And on December 11, the Youth of Tehran Neighborhoods Union, which has been labelled a “liberal oppositionist” tendency in an article published by Tempest Magazine, released a statement urging the formation of an opposition coalition. Iranian leaders in exile answered the Youth of Tehran’s demand for an opposition coalition just before the New Year.

Since September, a handful of other grassroots women’s and/or youth organizations or networks have formed or become better organized through the revolutionary struggle. Women and Youth Committee of Sanandaj Neighborhoods (WYCSN) is one such group that formed out of the mass movement. Its statement of October 14 declares that “the continuation of this resistance and its final victory depends on the persistent struggle and coordinated participation in all cities.” WYCSN is calling “on everyone to stand up against the reactionary forces of the regime by creating neighborhood committees, “especially in cities that have seen police and military leave to suppress protesters elsewhere.”

The Revolutionary Youth of Marivan and the Revolutionary Youth Council of Sanandaj are also calling for the formation of a revolutionary council movement. The Revolutionary Youth Council of Sanadaj is calling for the creation of councils to “help the scattered struggles for the youth to become more coordinated, to develop a program, to develop plans to choose certain tactics.” This call to action resembles the formation of workers’ and neighborhood councils in the 1979 Iranian revolution and demands for the formation of “showras,” or workers’ councils, in the 2019-2020 uprisings.

Furthermore, in October a network of women calling itself Voice of Baluch Women, and later Desgoharan[1], released two statements. The first statement describes that before the uprising, Voices of Baluch Women was involved in legal reform, anti-discrimination work, demanding more infrastructure for women suffering violence, access to “birth control measures,” documenting and publicizing femicides, and struggles against patriarchal practices and structures amongst their fathers, brothers, and tribe. As mass protests erupted, Voices of Baluch women found itself “at the forefront of the struggle.” Its second statement outlines its activism and declares that it is not part of any Party or organization.

What is significant about Voice of Baluch Women and the other women and youth organizations is that they show that the idea of freedom lives in the minds of the masses without the mediation of a Party to Lead or vanguardist organization.

Protests at Prisons, Universities, Businesses and Streets in 164 Cities

Protests broke out on December 18 at Qaem Shahr prison. Human Rights Activist News Agency (HRAW) does not give detailed information about the protests but does state that a clash between inmates and guards “occurred following the relocation of an inmate convicted of murder to carry out his execution.” HRAW also states that a protest broke out in response to the execution of several death-row inmates, the day before, at the Central Prison of Karaj.

These prison protests came two weeks after the first big wave of protests and strikes in December, which took place from December 5 to 7. On December 5 and 6, “the country witnessed widespread business closures” alongside “protests in several universities around the country” to mark Student Day. Protesters in Tehran chanted that the clerics should “get lost,” blocked a road in the Kurdish-populated town of Bukan, chanted “Death to the Dictator” in Mashhad, set fire to a statue in Dareh Sharht, lit fires in Sanandaj, and took to the streets in Rudsar, Qazvin, Esfahan, Kerman, Najafabad, Ahvaz, Ardakan, Tabriz, Zahedan, Shiraz, and Qorva. To date there have been protests in 164 different cities and at 144 universities.

Business closures, university protests, and strikes were followed by “silent marches from the main Revolution Square to the city’s Azadi monument” in Tehran on December 7.

Also on December 7, the government restricted access to the internet. Since then, protesters have found innovative ways to communicate and publicize their actions and ideas. One such tactic publicized by Middle East Matters is the “Snowflake Project,” a system that allows people from all over the world to access censored websites and applications by setting up internet servers that can bypass the regime’s attempts at censorship.

Another medium protesters have taken to is the social media app TikTok, where users are circumventing attacks by the regime on their phones and the internet through “clever use of labelling” and by “stitching and duetting” their videos with other users. WhatsApp, a popular encrypted texting app, adjusted its platform the first week of January to enable users to connect through proxy servers during black outs.

Meanwhile, solidarity rallies continued in North America, Europe, and Australia.

Women prisoners at Evin Prison who led a sit-in to protest executions of protesters. Credit: Iran Instagram page.

The Future of the Rebellion

There is no end in sight to the struggle between the Iranian masses and the regime. While Iranian Diaspora Collective emphasizes in its living document “How to Talk About Iran”—penned in consultation with Middle East Matters and From Iran–that “what Iranian people are asking for is not reform, but total regime change,” leaders of the Islamic Republic have “openly said that they will not repeat the mistakes of the Shah and will not retreat.” Therefore, compromise by either side is highly unlikely.

Despite this, commentators have begun to make predictions about whether the regime is close to collapse or not. Iranian-American scholar Kian Tajbakhsh recognized, in a recent interview with National Public Radio, that the movement has not yet been able to bring down the “three pillars of regime strength–a cohesive ruling elite, a highly developed, loyal coercive apparatus and the destruction of rival organizations and alternative centers of power,” meaning he does not predict any imminent collapse of the Islamic Republic. Nevertheless, Islamic Republic leaders are looking to Moscow for support in suppressing the protests and for sanctuary for regime officials and their families in Venezuela.

A recently formed coalition of right-wing and liberal opposition leaders in exile made a markedly different declaration. The coalition, which states that it has “no desire to assume power in Iran,” released a coordinated message claiming that 2023 will be a year of “victory.” But the emergence of this coalition, rather than ensuring the victory of the Iranian masses, compounds the contradictions in the movement.

The coalition states that it is unified “against the Islamic Regime” and “for the creation of a secular democracy, the restoration of human dignity, and equality among all citizens of Iran regardless of their gender, ethnicity, and beliefs.” Yet it did not include the protests’ main slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom” in its first announcement. The coalition’s omission of the pivotal slogan of the uprising and its friendliness to the idea of Western intervention suggest that there is division between the interests of the masses in Iran and the self-appointed leadership in exile.

Recent escalations in state violence, strikes, deepening of grassroots organization, continued protests, and the formation of an informal opposition reveal, not the outcome of the revolution, but its process of development. In other words, although it is impossible to predict the outcome of a revolution, it is possible to recognize the sea change evident in the bravery of the Iranian masses and their determination to achieve their own freedom. And it is crucial to recognize that, at a moment when the Islamic Republic has become the representation of death, “resistance is life!”

Note

[1] Taken from October 14 statement: Desgohari is a friendly social tradition among Baluch women for empathy, companionship, and sisterhood.

Be the first to comment