by Ralph Keller

Viktor Orbán, one of Europe’s right-wing populist rulers, was Hungary’s prime minister from 1998 to 2002 and again from 2010 to today. He was among the founders of Hungary’s Fidesz party, or Magyar Polgári Szövetség (Hungarian Civic Alliance). Under his reign, Fidesz was transformed from a liberal party to the dominant conservative party, now seeped in authoritarianism—this in a country that, in 1956, took up arms to fight for freedom against Russian tanks in the streets of Budapest.

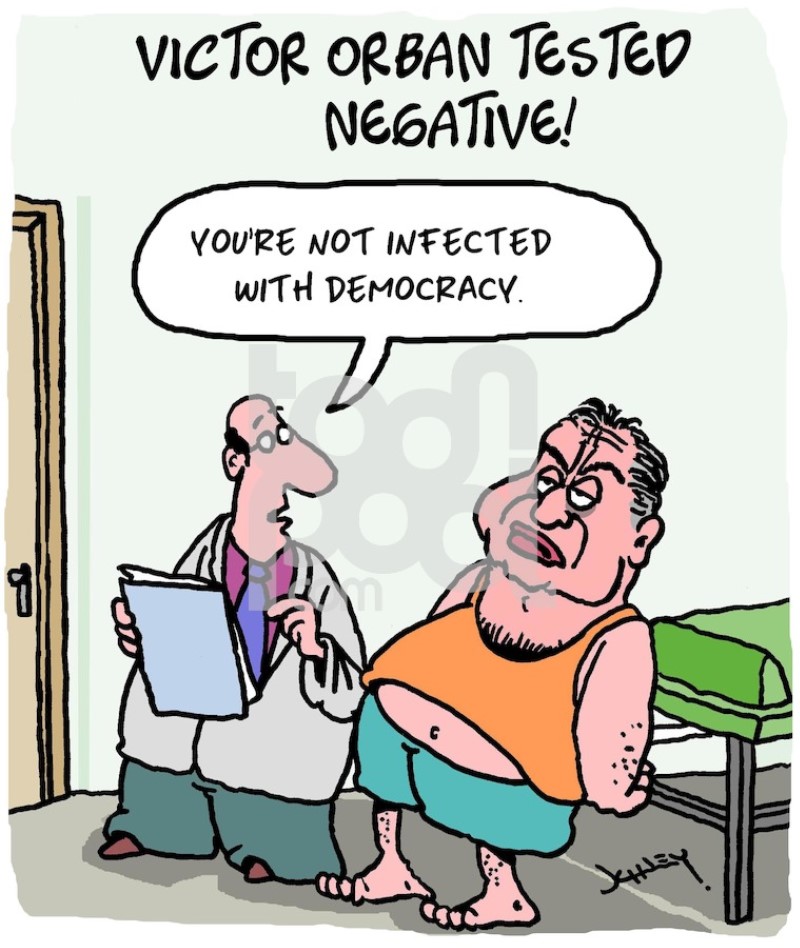

Authoritarianism and nationalism have become part and parcel of Fidesz. Orbán himself frequently emphasises the role of Christian churches and the traditional family (whatever that means—women stay at home, give birth and don’t ask questions?). And he openly projects his views, as quoted by Roger de Weck: “the new state we build in Hungary is no liberal state, but an illiberal one”. The winners in the race for the best state-form are, according to Orbán, “Singapore, China, India, Russia and Turkey”.[1]

To demonstrate Orbán’s policies of repression, discrimination and spreading fear, all of which are characteristics of authoritarian regimes, I first look at his attack on refugees and migrants, and then proceed to look more closely at his attacks on the free press, as well as the LGBTQ community and workers’ rights. These attacks not only prompted the EU to sanction the Hungarian government, but also triggered grassroots resistance within Hungary. Second, I look more closely at other, little-known attacks and the fightback by ordinary people within the country. I finish with a critical look at the European Union (EU), which had a hand in Orbán’s rise to “prominence”.

Orbán’s Attack on Refugees and Migrants

In her May 2021 Huffpost article, Rachel Wearmouth calls Orbán an authoritarian who is “illiberal and content to deploy racist tropes to maintain power”. This is correct, given Orbán’s major “achievements”. For example, he has described migrants as “poison” and “Muslim invaders”. Here are some examples of his tropes that Wearmouth quotes:

- “Hungary does not need a single migrant for the economy to work, or the population to sustain itself, or for the country to have a future”;

- “The factual point is that all the terrorists are basically migrants”;

- “Mass migration is threatening the security of Europeans because it brings with it an exponentially increased threat of terrorism”;

- “We know nothing about these people: where they really come from, who they are, what their intentions are, whether they have received any training, whether they have weapons, or whether they are members of any organisation. Furthermore, mass migration also increases crime rates”.

It goes without saying that this rhetoric is racist, xenophobic and chauvinistic. It has enabled Orbán to create a climate of hatred in support of, or at least non-resistance to, building a razor-wire fence on the borders with Serbia and Croatia during the Syrian refugee crisis. Refugees and asylum seekers were then detained and targeted with water cannons and tear gas. So it is actually the Orbán government that attacks and terrorises the migrants, not the other way around. From Donald Trump, with love.

In 2021, the European Court of Justice ruled “that Hungary broke EU law by making it a criminal offence for people or organisations to help asylum seekers and refugees apply for asylum”. And, in response to Orbán’s challenge of that ruling, Hungary’s high court upheld the European court’s ruling. In addition, Orbán’s war on refugees and asylum seekers met with grassroots resistance from the Hungarian people, for example, from MigSzol, a group that supports refugees in Hungary. The group “urge[s] Hungarians to realize that ‘refugees’ are not ‘economic migrants’ and the government’s border fence will not solve any problems”; it also says that “the fence is more of a propaganda tool to bolster support for Fidesz”. The statement that refugees are not economic migrants represents an important realisation that exposes the far-right rhetoric for what it is: toxic propaganda. The importance of the recognition that refugees are not economic migrants cannot be overstated in the struggle against authoritarianism. It is relevant not only to Hungary, but also to every other country under authoritarian rule.

An Attack on Hungary’s Media

Another example of Orbán’s authoritarianism is the infamous attacks on the country’s media and freedom of speech. The government established a media watchdog whose purpose is to suppress regime-critical media activity. Hungary avoids physical violence, but “has pursued a clear strategy to silence the critical press through deliberate manipulation of the media market”. Examples of this strategy are repeated attempts to close down the radio station Klubrádió, which was is critical of the government, and the large-scale rollout of spyware to keep tabs on journalists and other critical voices. Reporters Without Borders (Reporters Sans Frontières, RSF) has since added Orbán to its list of “predators”, saying that “The methods may be subtle or brazen, but they are always efficient”; and that the Orbán government “has steadily and effectively undermined media pluralism and independence since being returned to power in 2010”. In response, the Hungarian government said, in finest Donald Trump fashion, that Reporters Without Borders should be called “Fake News Without Borders”.

The attack on media independence triggered a bourgeois-style response from Brussels as part of a wider “crackdown” on member states that do not comply with EU values. Hungary and Poland have been at loggerheads with Brussels for some time—Poland because of its attack on the independence of its high court à la Donald Trump, and Hungary because of the attack on the media. Specifically, the European high court ruled that cash handouts to member states may now be contingent upon beneficiaries upholding EU values. This is a bourgeois-style response because it comes from “above”, but it constitutes a pushback against authoritarianism, at least within the “club” of member states. Making cash handouts conditional does not support the struggles of ordinary people, as would, for example, strengthening freedom of the press and Hungary’s LGBTQ community.

An Attack on Hungary’s LGBTQ Community

On 7 July 2021, the Orbán government implemented a law called the Children Protection Act, with the “purpose” of safeguarding children’s well-being and fighting paedophilia. The Act makes it “an offence to ‘promote’ sexual and gender differences to children in educational settings, films or adverts.” In response, the EU launched a lawsuit against Hungary. Unsurprisingly, the Hungarian government responded by saying, “How Hungarian children are raised is the exclusive right of Hungarian parents. Brussels has no say in this.” And: “It hurts the Brussels bureaucrats that LGBT LGBTQ activists are not allowed to get near children. The future of our children is at stake, and therefore, on this issue, we cannot compromise.”

Pro-LGBTQ protest on Budapest’s Szabadság híd (Liberty Bridge). Credit: henryclubs.com

But it is the Children Protection Act that interferes, not Brussels; it is the Orbán government that openly oppresses the LGBTQ community, not Brussels. In other words, it is the Act that interferes with parents’ rights to raise their children: what does teaching about LGBTQ rights have do to with paedophilia or children’s rights? Indeed, the Hungarian grassroots resistance is outraged; Dávid Vig, Director of Amnesty International Hungary, called the Act “a homophobic and transphobic law that blames the LGBTQ community for the crimes against children. So it makes consensual love of two people equal to a crime. It is unacceptable.” Clearly, gender differences and LGBTQ rights are the proverbial thorn in Orbán’s thigh, and he uses “protection of children” as a justification to shape society to his liking.

Encouragingly, the resistance within Hungary and a degree of pressure from the EU (fourteen member states backing a statement by Belgian’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sophie Wilmès, and the European Commission’s initiation of legal proceedings against Hungary) have had an effect: a referendum on the Act will be held on April 3, 2022. Yet Orbán is not backing off. An article in The Guardian notes that the referendum questions are worded in leading language, e.g., “Do you support minors being shown, without any restriction, media content of a sexual nature that is capable of influencing their development?” No one in their right mind would, and we do not need a law against that. Besides, this has no bearing on LGBTQ rights. The referendum might thus turn out to be a farce, so that Orbán will get his way even if he has to leave office after Hungary’s parliamentary elections, which will also held on April 3.

Other Struggles Against Authoritarianism in Hungary

The people of Budapest have been engaged in a little-known struggle against the government’s criminalisation of the city’s homeless. For example, a social worker, Norbert Ferencz, was placed on three-year’s probation in 2011 for protesting a by-law that forbids scavenging in bins. In 2013, the Hungarian Parliament voted to criminalise homelessness, which has allowed local governments to create homeless-free zones. This makes living in public spaces an offence, in the name of safeguarding cultural heritage sites. Plainly and simply, the legislation criminalises the homeless and drives them underground, so that care workers cannot find them. Hundreds have protested in the city of Budapest, yet to little avail. Fortunately, social workers do not need to struggle on their own and can draw on support from A Város Mindenkié (The City is For All), founded in 2009. The group fights the criminalisation of the homeless by organising protests, engaging in civil disobedience, raising awareness, and demanding the right to housing to be codified into law.

On 12 December 2018, the Fidesz majority in the Hungarian parliament passed what quickly became known as the “slave law”. This law allegedly addresses the country’s prevalent labour shortage in light of the government’s anti-immigrant stance. It permits employers to demand up to 400 hours of overtime per year from workers (an increase from 250 hours previously). Even worse, the law allegedly allows employers to pay for overtime, not at the end of the year, but only every third year! Protests erupted, for example in Budapest. These protests also opposed Hungary’s increasing corruption and its attacks on academic freedom. In one protest outside of parliament, which attracted a 10,000-strong crowd, grassroots protesters and the parliamentary opposition stood together. Csaba Molnár, a prominent member of the Democratic Coalition party, said that “[w]e are not rising up against one Orbán law or another, but against the many, many laws of the repressive regime”, and that “[w]e will continue to rise up until we topple Orbán’s rotten-to-the-core regime.”

Other groups have also turned up the heat on Orbán and Fidesz, e.g., the Milla movement (One Million Voices for a Free Press), which attempts to mobilise on Facebook against the Fidesz government. In 2015, Peter Wilkin characterised Milla as “an experiment with the use of social media as a means of organising social and political protest, with the ambition of undermining the government’s authoritarian policies”. While social media provided “an easy and instant way in which to try to mobilise and organise a widespread protest to Fidesz authoritarian agenda”, Wilkin also argued that this method of organisation showed some limitations. Specifically, “Hungary only has around 75% internet penetration and 43% Facebook penetration. Those excluded from this are precisely the people that Milla will need to win over, the poorest, most marginalised and dispossessed Hungarian citizens.” Milla then joined the Unity coalition (as part of the Together political party, which dissolved in 2018). This shows that movements may face technological challenges. But more importantly, it shows that they may dissolve or be taken over if they only take action without also aligning their action with theory.

Then there is a satirical party that calls itself the Hungarian Two-Tailed Dog Party. Its website is a fun read, with statements like: “[We] will certainly win the general elections. At some point. In the future”, and “[w]e took part in the 2018 parliamentary elections with a campaign budget of exactly 0 HUF.”[2] The party displays satirical signs at protests and rallies. One sign read, “I want to give birth to a stadium”, poking fun at two of Orbán’s projects, increasing the nation’s birth rate and filling the country with white-elephant sports facilities. The party has had some successes in its effort “to do things which actually produce results [in local communities], instead of responding to who said this and who did that”. Yet they do not take head-on the fundamental issue of authoritarianism in Hungary. In fact, I read its website as implicitly stating that they stay away from that struggle.

Hungary has a chance to oust Orbán and Fidesz from power in the April 3 general election. To do so, six democratic parties have formed an anti-Fidesz coalition, uniting behind conservative Peter Marki-Zay. The hope is that this unity would end Hungary’s authoritarian politics and promise to restore basic freedoms for ordinary Hungarians. We will see.

The EU Itself Has a Way to Go

The EU has tolerated Orbán for too long. It is thereby partly to blame for his rise to “prominence”––which does not diminish Orbán’s authoritarianism or absolve him in any way. Only recently has the EU started to act against Orbán’s and Fidesz’s rule. And the EU itself has a way to go in terms of fighting authoritarianism as well as discrimination.

Criminalisation of the homeless, the most vulnerable group in capitalist societies, has become a widespread problem in the EU. And last August, a report issued by a Spanish hospital described a teenager’s homosexuality as an illness. This incident is not the kind of open oppression that takes place in Hungary, yet it still is an act of discrimination. It appears that, in EU countries other than Hungary, the LGBTQ community is merely tolerated, which is a long way from being accepted. This widespread climate has made it easy for Orbán to discriminate and wage war against certain groups within Hungarian society.

As for toleration of authoritarianism, “[i]nterviews with more than a dozen current and former European officials show how sentiments toward Orbán and his illiberal project evolved from complacency and incomprehension to a recognition that he had become a serious internal threat”.

It all started with other EU national leaders brushing the issue under the carpet, and with a consensus of “staying out of one another’s affairs”. Symptomatic of this view was an episode of wilful neglect in 2015, when Jean-Claude Juncker (then President of the European Commission) gave Orbán a pat on the face and said “[t]he dictator is coming”.

At long last, however, it appears that the EU got its act together to address the issue of authoritarianism, albeit in a bourgeois way. As I noted above, the EU has made receipt of cash handouts conditional on upholding certain values and principles, and the European Court of Justice has ruled that Hungary broke EU law when it made it a crime to save refugees from drowning in the Mediterranean Sea. This may prove to be a landmark ruling, since it might protect groups like MigSzol, and rescue-ship captains like Carola Rackete (who received the Grand Vermeil Medal from the city of Paris for saving migrants at sea) and Claus-Peter Reisch, from prosecution in individual member states throughout the EU.

Bringing authoritarian leaders down by open protest and resistance requires basic bourgeois liberties to be in place for ordinary people. Without these liberties, struggles will be driven underground, exist in a criminalised realm, and have little if any impact. In other words, basic liberties are vital—not only in one country, but globally. So far, despite the tendencies to the contrary, the EU has guaranteed these basic liberties by upholding them through court rulings. However, if people do not keep resisting, these liberties will be taken away in the future.

ENDNOTES

[1] de Weck, R. (2020). Die Kraft der Demokratie. Eine Antwort auf die autoritären Reaktionäre. Berlin: Suhrkamp, p. 114.

[2] HUF is the symbol for the Hungarian forint, the nation’s currency unit.

Well, Fidesz won the elections.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/apr/03/viktor-orban-expected-to-win-big-majority-in-hungarian-general-election

Fidesz improved on it’s 2018 results, by +3.82%; the coalition led by Peter Marki-Zay lost a whopping 12.8%.

While it is not clear why the opposition lost so badly, there are attempts to explain why Fidesz won according to this Washington Post article.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/04/06/orban-fidesz-autocratic-hungary-illiberal-democracy/

One reason is gerrymandering so that seat allocation in parliament will be in Fidesz’s favour. The second reason is that Orban manipulates peoples fear of war. Third, there was what the Washington Post calls “autocratic cheating”: excepting young people from tax payments, freezing mortgage interest rates and fuel prices; and forcing public office workers to vote Fidesz.

Another view of Orban/Fidesz’s victory:

https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/orban-victorious