by Eve Currie

Unrest and protest by workers in the gig economy has been growing steadily across the globe over the past year. International coordination of industrial protests and strikes has gone hand-in-hand with the workers’ articulation of the inter-related nature of the features of their exploitation, such as low wages, irregular hours, and sexual harassment.

‘McStrike’ Sweeps UK and US Fast-Food Industries

Late last year, dissent exploded with a series of coordinated strikes across four continents by workers in the fast-food industry. Nicknamed ‘McStrike’ and tagged #ffs410 (fast food shutdown on 4 October), industrial action involving workers from McDonald’s, Wetherspoons, TGI Fridays, Uber Eats and Deliveroo took place in seven UK cities, and a rally was held in London’s Leicester Square with international speakers (see Nationwide Fast-Food and Hospitality Workers Strike—Call of the Precariat!). This action was supported across numerous cities across the length and breadth of the UK, with some customers walking out in solidarity.

On the same day, in seven states throughout the US, fast-food workers, in tandem with hospital, airport, childcare and higher education workers, concluded a two-day strike, protesting pay and working conditions. Under the banner Fight for $15, the workers linked their demands for better pay and working conditions with their participation in the US midterm elections in November. This strategy succeeded in pressuring members of the new Congress to introduce legislation in January to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour.

Striking fast-food workers in the Twin Cities, USA, were joined by university workers, students, janitors, retail workers and airport workers. They called for a $15/hour minimum wage, paid sick days, and fairer scheduling of work hours. Source: Fibonacci Blue, Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Uber Eats and Deliveroo Drivers Strike

Strike action by employees in the gig economy is historically rare, which makes recent action by drivers and couriers for Uber and Deliveroo particularly notable. On 20 September, just two weeks before the coordinated action on 4 October, non-union, self-employed Uber Eats drivers spontaneously abandoned their deliveries, bringing traffic to a standstill as they blocked roads outside the company’s headquarters in Aldgate. Chanting ‘No money and no food’, they protested against their low pay.

On 4 October, in solidarity with the fast-food workers industrial action, Uber Eats drivers teamed up with Deliveroo drivers in Bristol (UK) to hold a street protest that shut down traffic. Demanding better pay, they chanted ‘Power to the riders, not the corporation. Uber can you hear us, louder by the hour. Louder. Power’. And with neither of these groups’ demands having been met, their protests continue. Deliveroo drivers took to the streets again throughout December and January, while the battle that Uber Eats drivers began on the streets has developed to encompass Uber’s attempts to deny drivers employment rights.

Workers Voice Their Shared Interests Across Industries and Across the World

A most significant aspect of this spate of recent action is the evidence of workers building up their associated power. Recognising their strength in numbers, they are voicing their shared interests, across industries and across the world. And evident in the words and deeds of those taking industrial action is the fact that links are being made among a number of different issues. During the ‘Fight for $15’ protests in October, McDonald’s workers carried banners which read ‘#metoo McDonald’s–fight for $15’, referring to the recent strikes in relation to allegations of sexual harassment in US McDonald’s restaurants and workers’ demands for better pay. By linking these two issues, workers are expressing their awareness that rather than being unrelated, instances of sexual harassment and low pay are symptoms of the same issue: exploitation.

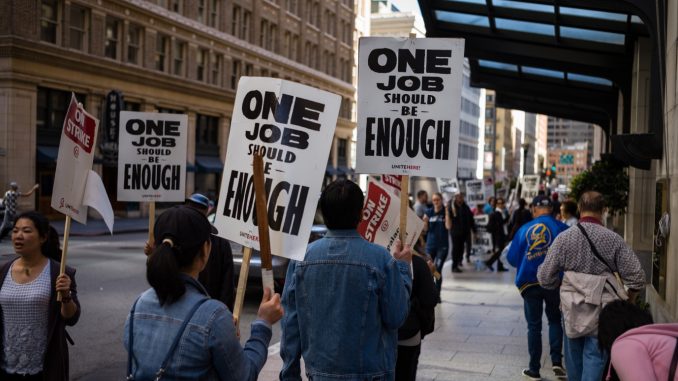

Workers are also pointing out that the low-paid and casualised nature of employment is in itself a cause of their hardship. This can be seen in the strike action that began last October at Marriott hotels in nine major cities across the US, from Detroit to Hawaii. Striking workers picketed under the banner, ‘One Job Should Be Enough’ (a reference to their need to have a second job to earn a living).

They also drew attention to the fact that their own immiseration is the other pole of the billions of dollars being accumulated by their employers. This was articulated in the complaint that ‘We’re the ones that make them their billions…They say it will trickle down, but it never trickles down.’ In doing so, they debunked the myth of America being a land of opportunity and simultaneously pointed to the fact that their exploitation is a component part of how the hotel industry operates.

Marriott Hotel Strikers Link Low Pay and Sexual Harassment

Marriott workers picket in San Francisco. Source: Bastian Greshake Tzovaras, Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The case of the Marriott strikers is an example of workers drawing attention to the multifaceted nature of exploitation. In addition to their low wages, the workers drew attention to sexual harassment, and made demands to end it. And there is also evidence to suggest that growing anger and discontent over racial inequality fuelled the recent strike action. Kate Bronfenbrenner, the director of Labor Education Research at the Cornell School of Industrial and Labor Relations, said ‘When the boss says “trust me” to a woman of color, “someday you’ll make it to the top,” they look at the top and it doesn’t look like it’.

Under capitalism, workers, who have nothing to sell but their labour-power, are not free to choose how to live or work. Their lives depend on a system of exploitation whereby their employer is compelled to realise the greatest profit for the least expense, i.e., low wages. And low-skilled workers are particularly vulnerable to extremes of deprivation because their labour is plentiful and they are therefore expendable.

Workers don’t need to be able to explain Marx’s category of exploitation in order to understand it. The majority of workers in the hospitality and catering industries know exploitation because they live this reality every day. They know that unless they put the needs of their employer ahead of their own needs or their family’s needs, they are at risk of losing their jobs. It is this fundamental relationship of inequality and exploitation that underpins the sexual exploitation which has been highlighted as rife in the low-pay sector. The coordinated strike action by food and hospitality workers in the US proves that, not only do workers understand exploitation, they are able to actively resist it.

Workers Battle Multifaceted Layers of Exploitation—and Sometimes Win

It becomes evident, through listening to the concerns of those taking strike action, that workers share a keen awareness of the inter-related nature of many aspects of their exploitation. During their industrial actions, hospitality workers pointed out that fluctuating working hours mean their eligibility for healthcare provision changes month-to-month, and they demanded that the working hour requirement for access to healthcare be lowered. Responding to the very real risk of sexual assault within the hotel industry, workers’ demands included the call for panic buttons to be issued to those who work alone. And a keen awareness of the particular vulnerability of migrant workers to exploitation within the hotel industry led striking workers to demand that hotels be barred from cooperating with immigration authorities.

In light of these demands, strike action becomes about much more than pay. Workers are aware of the full experience of being human and are bringing this knowledge to bear on their aspirations and demands.

The evidence of the success of this wave of industrial action is that, across all Marriott hotels in the US, striking workers won significant concessions. Up against an international corporation keen to prevent unionised staff, hotel workers out-organised Marriott. In November, they began returning to work victoriously as agreements were reached in different states. Only in December, once the last agreements on wage increases, job security, healthcare, immigration and union rights as well as improved health and safety were reached, were the terms of each settlement made public.

While their deals varied according to cost of living and ‘union density’, it is interesting to note that gains made to protect staff from sexual harassment were nationwide. All staff who deal with guests one-to-one will carry a silent panic alarm, and staff who cite an incidence of sexual harassment will have the right to have no further contact with the guest involved. This marks a significant advance for vulnerable workers, who are vulnerable because of their position within capitalist relations of production. In spite of this relationship, these workers’ actions show, precisely, that when they stand together, ‘vulnerable workers’ have the power to take on huge corporations.

Be the first to comment