by several MHI members

Hundreds of thousands of women and men marched against Trump and Trumpism for the third year in a row on January 19. Smaller than the massive marches around the world on the very day after Trump’s inauguration in 2017, they were still huge and took place all over the US—as well as in London and elsewhere.

MHI took part in marches in New York and Philadelphia, and received reports from Los Angeles and Portland, Oregon. The marches took place in the middle of the partial government shutdown that Trump instigated, so a major theme everywhere seemed to be, “shut down Trump, open the government.”

We also participated in the Women’s March in London. See Jolanda Knott’s full report on and analysis of the London march later in this article.

Calling for an end to the discrimination against women and their denigration in Trumpian culture, signs in New York City reminded us about the Senate hearings on Kavanaugh and the woman he was credibly accused of having assaulted, saying: “We still believe Christine Blasey Ford.”

Uteri give Trump and Trumpism the finger at New York City Women’s March. Photo by MHI.

This year’s marches were smaller than last year’s and, especially, than the historic, Resistance-launching Women’s Marches that took place two years ago. No one knows for sure why attendance fell off, but commentators have generally opined that the controversy over anti-Semitism that erupted in the Women’s March movement is among the reasons. The immediate cause of the controversy was the refusal of the Women’s March, Inc. leadership to forthrightly denounce Nation of Islam chief Louis Farrakhan and his anti-Semitic doctrines. Tamika Mallory, the co-president of this group, which organized the original march in Washington in 2017, has openly praised Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam. While the Women’s March group has condemned anti-Semitism in public statements, Mallory apparently remains unwilling to condemn Farrakhan, a figure well-known for his promotion of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, Holocaust denialism, and Jew-hatred. There were also allegations of anti-Semitism within the group toward its members, causing some of the original members to leave.

In contrast, the flyers MHI distributed at marches in the US and London pulled no punches. They denounced the anti-Semitism, as well as the misogyny, of Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam in no uncertain terms:

some Women’s March leaders have praised an influential American anti-Semite, Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. He has a long history of calling Jews the devil as well as calling for the subordination of women to men. Even when some women “leaders” were recently confronted about the issue and condemned anti-Semitism in the abstract, they have continued to praise or associate with Farrakhan.

… We call for the immediate, loud and clear, repudiation of Farrakhan’s views and a call to fight anti-Semitism. We also call for discussion on how to uproot reactionary ideas from our movements, and how to form and maintain principled leadership.

Adding to the controversy over Women’s March, Inc. was its failure to disclose who its leadership is, which caused some organizations to withhold funds from it this year, including Planned Parenthood of New York and the Democratic Party. The “leadership” secrecy is also ensnared in the issues of diversity in color and gender. (MHI’s full flyer appears below.)

Moreover, Women’s March, Inc. refused to join with the sponsors of other marches, and held their own, separate marches in some cities, even where there were already established Women’s March organizations. New York’s Women’s March Alliance had organized the original 2017 march in that city; this year, like last, there were two completely separate events. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a freshman Congresswoman and self-proclaimed “democratic socialist,” spoke at the Women’s March Alliance rally on the Upper West Side, but also spoke at the rally at Foley Square organized by the Women’s March, Inc. group.

In Philadelphia, there were also two separate rallies this year, just two blocks apart. In 2017 and 2018, the Philadelphia Women’s March was organized by a local group that is unaffiliated with Women’s March, Inc. This year, however, the latter seems to have tried to completely take over the march, without establishing any contact with the local organizers. In the end, the local group and Women’s March, Inc. agreed to organize two separate events. But Women’s March, Inc. made no mention of the locally organized event in their publicity, which made it look as if they were the only game in town. In a radio interview, a Women’s March, Inc. organizer warning listeners not to be confused by other events also called “Women’s March.”

The crowd at the locally organized rally, held at the Art Museum, seemed smaller than last year’s. Yet a significant number of people were spread up and down the parkway between the two rallies. They may have been drifting from one to the other. There seems to have been a lot of confusion about which rally to attend, and about why there were two rallies in the first place.

Outside of the US, the third anniversary saw marches and rallies in several cities across the globe. Here, too, turnout is reported to have been smaller than in the previous years. The New York Times reports that in Rome women, “chanting against fascism,” protested the populist government of the League and the Five Star Movement, which has advanced attacks on women’s rights and migrants. In Berlin, a crowd of 2000 marched against a Nazi-era law that prevents doctors from advertising abortion services. The Times also makes note of protests against the right-wing government, led by the Popular Party and supported by Vox, that took power in Andalusia.

“Girls Are Grrreat” tiger atop man at New York City Women’s March. Photo by MHI.

Third London Women’s March Shows the Strength of Radical Feminism

by Jolanda Knott

This year’s London Women’s March was named “Bread and Roses” in memory of the Polish-born, Jewish American socialist and feminist Rose Schneiderman. Schneiderman was secretary of the New York City Central Labour Union, and a founding member of American Civil Liberties Union. She was speaking after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 which killed 146 workers, most of whom were young women aged 14-23. Speaking to a largely middle-class crowd, she appealed to the women: “What the woman who labours wants is the right to live, not simply exist – the right to life as the rich woman has the right to life, and the sun and music and art. You have nothing that the humblest worker has not a right to have also. The worker must have bread, but she must have roses, too. Help, you women of privilege, give her the ballot to fight with”.

The demonstration this year drew between 2500-3000 people starting with dance and music outside the BBC offices on Portland Place and then marched down Regent’s Street to hear speeches at Trafalgar Square. This was the third annual Women’s March coinciding with the US Women’s marches held after the day of Trump’s inauguration and last year. The first London Women’s March after Trump’s inauguration drew a massive mixed crowd, not only of independent feminist activists, but also the left and liberals and those who did not see themselves as political. Unlike past years, the clear majority on this much smaller third year of the Women’s March were feminist activists. There had been much less mainstream media coverage prior to the march and not even that much of a buzz about it on social media platforms. Many people mentioned they had only been alerted to it happening late in the build-up.

London Women’s March. Photo by MHI.

People of all ages carried banners that demanded: gender equality, a stop to sexual harassment and an end to austerity, which disproportionately affects marginalised women.

Several of the speakers were immigration activists, including Monica Aidoo from Women for Refugee Women who highlighted immigrant women’s right to not just live but to thrive in the UK. Signs against Brexit, racism and for immigrant rights were seen among the marchers.

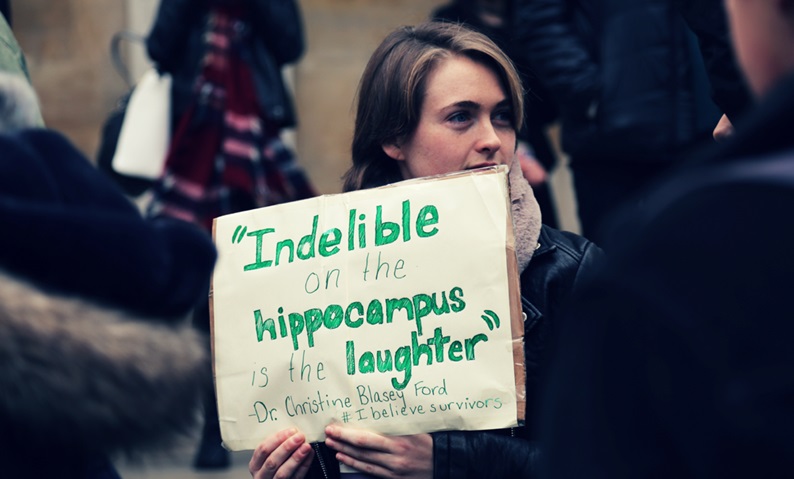

The US origins of the Women’s March were evident in the way people referred to Trump’s threat to women’s rights, with people aligning themselves against the President with banners declaring “We Are The Resistance”. Another expression of solidarity with the people of the US suffering under Trump, was a quote from Dr Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee, for the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh as a Supreme Court judge. Ford credibly accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her. The sign read: “Indelible on the hippocampus is the laughter” in reference to Ford’s memory of the assault on her by Kavanaugh and his friend.

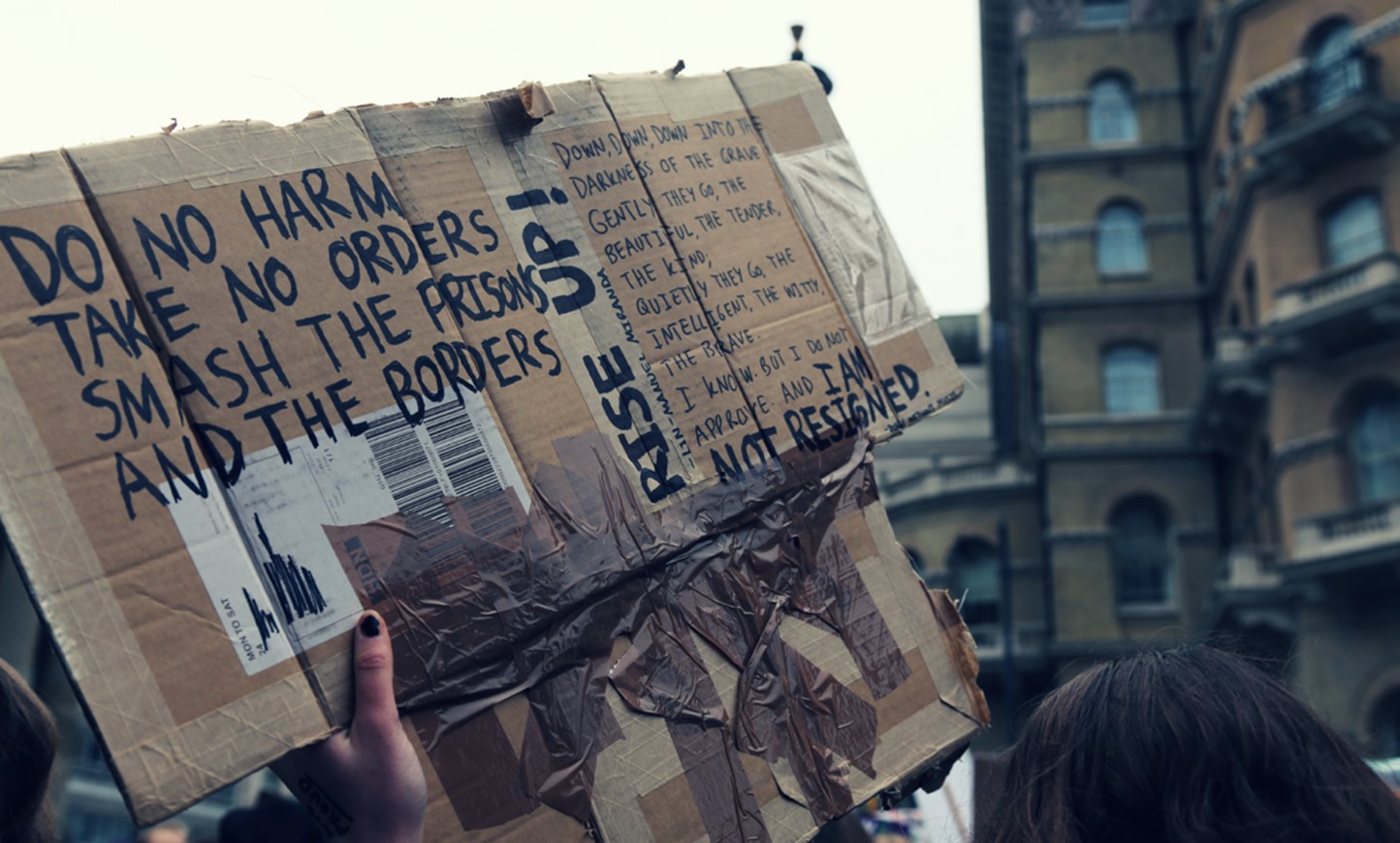

The awareness of feminism’s challenge to the very nature of this society was shown on the banner slogans: “Do no harm, take no orders, smash the prisons and the borders” and “The power of the people is stronger than the people in power”.

London Women’s March. Photo by MHI.

This multicultural and multidimensional feminism is concerned with issues beyond women’s rights, and is taking up women’s rights as part of a broadly interrelated struggle for equality and dignity for everyone. This desire to break down hierarchy and find equality for everyone, that has long been a part of the women’s movement, is an anticipation of a different kind of society.

Be the first to comment