by Aaron Williams

To paraphrase Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities––today is the worst of times and the best of times. In spite of the Covid-19 worldwide pandemic and attendant economic crises, people are in motion everywhere. Whether it is workers fighting their bosses about unsafe working conditions, or Hong Kong residents fighting Chinese authoritarianism, or Black Lives Matter activists fighting racism and police violence, “new forces and new passions”[1] have arisen in the global struggle for freedom from exploitation and all forms of oppression––economic, political, racial, ethnic, gender––and for freedom for self-realization as complete human beings. This is the essence of Marxist-Humanism, a philosophy of human liberation originating in the writings of Karl Marx[2] and further developed by Raya Dunayevskaya, in the books she called a “trilogy of revolution”[3] and in thousands of pages of journal articles, newspaper columns, letters, and talks.[4]

Last year, Marxist-Humanist Initiative (MHI) sponsored a reading group on Marxism and Freedom, from 1776 until today for members, supporters and friends. It is important to note that the reading group was held during the peak of the mass movements (e.g., BLM protests over the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and many others in the U.S.) that were emerging at the time of the scheduled classes, as well as during the time of the Covid-19 lockdowns.

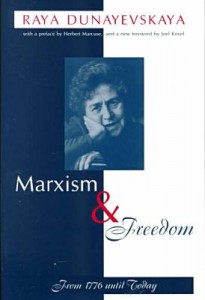

Raya Dunayevskaya’s Marxism & Freedom

The rationale for the MHI reading group was to introduce the underlying core concepts of Marxism and Freedom that Dunayevskaya developed into a full-blown philosophy (Marxist-Humanism). Her intended audience was the new forces emerging in freedom struggles––blacks, women, youth, rank-and-file workers––whom MHI also wishes to work with. Since MHI classes are not “talking shops,” however intellectually interesting they might be, the important aspect is that new struggles open up and expand new ideas of freedom that, in turn, need to be developed with, and projected into, mass struggles. Such a unity of action and ideas can assist in the self-development of the mass movements for freedom.

Dunayevskaya’s Early Years

This commentary will not attempt to cover Dunayevskaya’s whole life or work, but will concentrate on her first book, Marxism and Freedom, from 1776 until today (1958). Before considering the text, we start with some background on Dunayevskaya, who today is not widely known.[5]

From her early years until her death, Dunayevskaya was a self-educated revolutionary. She was born in Ukraine (then part of Russia) in 1910 and emigrated with her family to the U.S. in 1922. Her political involvement began as a teenager in Chicago, where she was active in the Black movement and the Communist Party youth organization. She was literally thrown out of the latter for asking if they shouldn’t wait to see evidence before denouncing Trotsky. Subsequently, she joined the Trotskyists in NYC. In 1937, she went to Mexico, where Trotsky had been given asylum by the government, and she worked as his Russian language secretary for two years.

In 1939, following the Hitler-Stalin pact, Dunayevskaya broke with Trotsky over his analysis of the nature of the Soviet Union. Trotsky characterized it as a “degenerated workers’ state,” which had to be unconditionally defended despite the fact that it was not then (nor later) a socialist or communist society.

After returning to the U.S., Dunayevskaya joined the Trotskyist Workers’ Party (WP-US) in 1940. The Workers’ Party rejected Trotsky’s and the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party’s (SWP-US) theory that Russia was a “degenerated workers’ state” and, instead, characterized it as a new form of class society they called “bureaucratic collectivism.” However, in opposition to this Workers’ Party majority position, Dunayevskaya, in collaboration with C. L. R. James––a black Marxist intellectual from Trinidad––developed the theory of “state capitalism.” Together they formed the Johnson (James)-Forest (Dunayevskaya) Tendency (JFT) within the Workers’ Party.

This was a theoretically productive period. The JFT eventually ended up leaving the Workers’ Party over differences in theory and practice, and later formed its own organization, Correspondence Committees, in 1951. In 1955, that organization divided into two new organizations; Dunayevskaya formed News and Letters Committees (N&LC) and James formed Facing Reality.[6] The latter eventually dissolved around 1970, while Dunayevskaya led News and Letters Committees until her death in 1987.

After her death, the organization she had worked over 30 years to build appears to have devolved into little more than a journalist publishing house and a museum for Dunayevskaya’s writings. In contrast to what is left of N&LC, Marxist-Humanist Initiative (MHI), founded in 2009, is a “…freely associated collective that seeks to rebuild an organization capable of projecting, developing, and concretizing the bodies of ideas of Karl Marx and of Raya Dunayevskaya (1910-1987), who founded Marxist-Humanism in the U.S … [and] aim[s] to renew the legacy of Marxist-Humanism for the new times in which we live.”[7]

The Genesis of Marxism and Freedom

Marxism and Freedom (M&F), published in 1958, was written after her final break with Trotskyism (both as a political theory and as an organizational structure), her break with C. L. R. James, and the formation of N&LC.

Hungarian Revolutionaries celebrate the toppling of a statue of Stalin. Credit: The Cold War In Depth

Originally, Dunayevskaya had planned a continuation of her earlier JFT analyses of state-capitalism, to show how the Soviet Union under Stalin had been transformed into state-capitalism and was not a workers’ state, let alone socialism or communism. But, in light of the 1953 uprising in East Germany and the emergence of civil rights struggles and workers’ struggles against automation in the U.S., she modified her earlier plan. A deeper dive into economic analysis alone seemed inadequate to understanding these emerging struggles for freedom. For Dunayevskaya, “Marxism is a theory of liberation or it is nothing” (Marxism and Freedom, p. 22). And to further develop a philosophy of freedom, she returned to the dialectical, emancipatory philosophy of Marx that is the ground for the book. She wrote (Marxism and Freedom, p. 23-24):

No theoretician, today more than ever, can write out of his own head. Theory requires a constant shaping and reshaping of ideas on the basis of what the workers themselves are doing and thinking. …In its beginning, this work was a Marxian analysis of state capitalism. But it did not take its present form of MARXISM AND FREEDOM until the new stage of production and revolts was reached in 1950-53.

It is also instructive to note that writing the book was assigned to her by N&L at its first convention in 1956, and some of the core ideas and principles of the book were memorialized in the N and L Constitution:

At the founding convention of NEWS & LETTERS COMMITTEES we both established the Paper and set for ourselves the task of putting forth our own interpretation of Marxism in book form. In our Constitution, which we adopted then, on July 8, 1956, we wrote: “We hold that the method of Marxism is the guide for our growth and development. Just as the struggle for the shortening of the Working Day and the Civil War in the United States gave shape to Marx’s greatest theoretical work, CAPITAL, so today, Marxism is in the lives end aspirations of the working people. We hold it to be the duty of each generation to interpret Marxism for itself because the problem is not what Marx wrote in I843 or 1883 but what Marxism is today. We reject the attempt of both Communists and the [U.S.] Administration to identify Marxism with Communism. Communism is totalitarianism and the exact opposite of Marxism which is a theory of liberation.”[8]

Some Core Principles in Marxism and Freedom

As a brief overview, here are a few of the core ideas and principles presented in Marxism and Freedom. Looking back on the book from the vantage point of 1985, Dunayevskaya lists three main goals of the book:

The three-fold goal of Marxism and Freedom was: 1) To establish the American roots of Marxism, not where the orthodox [Marxists] cite it (if they cite it at all) in the General Congress of Labor at Baltimore (1866 ), but in the Abolitionist Movement and the slave revolts which led to the Civil War; 2) to establish the world Humanist concept which Marx had, in his very first new moment, called “a new Humanism,” and which became so alive in our age and led to Marxist-Humanism; and 3) to reestablish the revolutionary nature of the Hegelian dialectic as Marx recreated it and as it became compulsory for Lenin at the outbreak of the First World War, gaining a still newer life in our post-World War II age.[9]

The author stresses the continuity of humanism — as a “red thread” or philosophy of freedom and human emancipation — beginning with Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and throughout all of his subsequent writings and practice, including Capital. His humanism was further developed and concretized by Dunayevskaya in this book.

Beginning in the 1940s, Dunayevskaya turned to the philosophy of German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, who greatly influenced Marx. From this theoretical deep dive came Dunayevskaya’s “Letters on Hegel’s Absolutes, May 12 and 20, 1953,”[10] which she later considered to be the “philosophical moment” from which her philosophy developed. What she saw in Hegel’s philosophical concepts of “Absolute Idea” and “Absolute Negativity” was a dual movement from theory to practice and from practice to theory. To her, the unity of the movements is necessary to the achievement of freedom and self-actualization of the masses in struggle. This became the underlying theme of Marxism and Freedom.

Marxism and Freedom shows us that mass struggles are, at root, struggles against exploitation and all forms of oppression (economic, political, racial, ethnic, gender), and struggles for freedom for self-realization as complete human beings in a new society. As she puts it (p. 286):

… a new society is THE human endeavor, or it is nothing. It cannot be brought in behind the backs of the people, neither by the ‘vanguard’ nor by the ‘scientific intellectuals’. The working people will build it, or it will not be built.

In this respect, the spontaneist belief that pure activism is a sufficient condition for a revolution against capitalism, or the belief (of Stalinists, Maoists, Trotskyists) that a “vanguardist” party is necessary to lead the masses to the promised land, are one sided and reverse images of the same coin.[11]

For Dunayevskaya, theory is not a monolithic concept that is fixed in time, but, instead, needs to be continuously developed out of engagement with the new ideas and social movements of the times. Otherwise, one is left with activity that is, at best, little different than reciting the catechism.

Right from the beginning of the book, the focus, front and center, is on the laborer (not labor as a “factor of production,” as in classical and neoclassical economic theory) and the nature of labor/work/production––the quintessential human activity––under capitalism. For Marx and Dunayevskaya, the production process is central to the functioning and understanding of capitalism, where the worker is subordinated to the machine, fragmented into hands without a head (the division between mental and physical work) and alienated from the products she produces.

Related to this, Dunayevskaya also focuses on, and identifies with, struggles against the capitalist and state-capitalist systems, e.g., struggles against “forced” labor (be it in Russia or the West), and against the dehumanizing and alienating conditions of work. The struggles began under a nascent capitalist “machinofacture” system (opposed by the Luddites and Silesian weavers), and continued on to automation (in the U.S. and Soviet Union). For Dunayevskaya, the history of struggle is evidence of the inherent conflicts within and generated by capitalism. Out of the these emerged “new passions and new forces” (human agents of change), whose goal was a “new society” beyond capitalism, in which “freely associated labor” has abolished value production and alienated work.

In addition to the mass movements since 1776 that are analyzed in the book (French Revolution 1789, Paris Commune 1871, Russian Revolution 1917, East Germany 1953, and Hungarian 1956), Dunayevskaya examines the concurrent emergence of new ideas and revolutions in theory such as political economy (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Marx), politics (Lenin, Trotsky and Mao) and philosophy (Hegel, Marx, Lenin’s notebooks on Hegel’s Logic), and their impacts. Theory, she illustrates, is both a means of analyzing the world and of changing it.

She also introduces what is new: the emergence of new forms of workers’ organizations, like workers’ councils (Soviets in Russia) and new forms of struggle, like boycotts and sit-down occupations. These arose as natural parts of the struggles themselves, and not as innovations of self-styled leaders of the masses.

Throughout the book, the question of “what comes next after the revolution?” is in the forefront. To answer that involves the imperative for a theory of liberation. Here Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program is indispensable. Also, the issue of “what comes after” is raised by Dunayevskaya, principally against the left (whom she later called “post-Marx Marxists”). In her view, Marxists after Marx failed to develop his theory, leaving a legacy only of spontaneity and vanguardism/substitutionism to this very day.

The Importance of Theory in the Renewal of Marxist-Humanism

To understand the emergence of new struggles which open new ideas of freedom, in Marxism and Freedom Dunayevskaya analyses past movements, ranging from the sans culottes in the French Revolution, the Luddites in England in the early 1800s, the Russian Revolution, and the Hungarian Revolution.[12] These were among what Dunayevskaya characterized as movements from practice––the masses’ struggles from below for “universality” (freedom).[13]

However, Marxism and Freedom should not be considered only as an historical review and assessment of revolutionary struggles. For Dunayevskaya, such struggles alone are not sufficient to achieve and/or maintain a new society. On one level, what is missing is a focus on abolishing capitalism (not just getting rid of an authoritarian, racist bosses, corrupt political leaders or public officials, or an authoritarian government) and capitalism’s total personal, social, and economic impact on all of us. On another level, the even harder question is “what comes after” the revolution. Using Hegelian terms, while the negation of capitalism may be achieved (e.g. as in the Russian Revolution, at first), “what comes next”?

G. W. F. Hegel

While Dunayevskaya saw the seeds of the second negation — the “negation of the negation” or creation of the new — within the first negation, the self-development of mass movements requires self-development of the mass movements from within themselves. Without an accompanying vision and understanding of what comes after the first negation, the mass movements are likely to regress or be compromised by objective conditions and ideas that seek compromises with, or reforms of, capitalism (or state-capitalism), instead of moving on to a new society. In short, in addition to movements from practice, revolutions also need what Dunayevskaya characterized as movements from theory to practice––a dialectical process whereby the ideas and principles of Marx’s humanism are developed in dialogue with the masses (but not in substitution for the masses), and are unified with the masses’ self-activity.[14] When there is a dialectical unity of the masses’ self-directed activity and a philosophy of liberation, the masses achieve a new stage of cognition (self-development) and push the struggle for freedom forward. Again, from the “News and Letters Committees, Draft Resolution on the Book Marxism and Freedom: Method, Heritage, and Principles” (1956):

As the book [Marxism and Freedom] makes clear, we are only moving toward a new unity of theory and practice, toward which there are strong objective pulls and subjective movements, of which we are only a small part. While we hope to become a polarizing force, we recognize: (l) that there will be those “greater than us” who will come forward in this unification of theory and practice, and (2) that the only ones who can possibly bring it to life are the masses themselves. Only when that is a reality do you have a new society.[15]

Why Read Dunayevskaya Now?

On the surface, Marxism and Freedom is an exposition and analysis of what has gone before: the masses fighting for a new society. But, at a deeper level, Marxism and Freedom is an exposition and application of the core principles of Marxist-Humanism that emerge in, and could guide, the struggles of the day to reach a society of free and complete human beings. This dual movement of masses’ self-activity (practice) and the continued development of Marx’s philosophy makes Dunayevskaya unique and relevant today. The so-called left ignores or rejects her– her history, writings and concept of organization — out of ignorance, sexism and/or the theoretical hegemony of spontaneism, vanguardism, and social democratic populism. Those are antithetical, both philosophically and practically, to the self-emancipatory vision in Marxism and Freedom.

There is an alternative to capitalism––a new society created by the “negation of the negation” of capitalism. What happens next is yet to be determined, but is currently in the process of unfolding. Marxism and Freedom is a starting point not only for understanding the past but also as a source of ideas for achieving a free future. What is needed now is the renewal of theory, philosophy, and organization to help develop the mass movements to the point where they can overthrow the system that exploits and oppresses us all, and go on to create a society in which humans are free to develop themselves.

More concretely, how Marxism and Freedom “comes to life” now is explained in the following “Statement of Principles of Marxist-Humanist Initiative” at its founding (as amended):

We strive especially to include workers, women, African-Americans, Latinos, other minorities and youth in our project. We base ourselves on the identification of multiple forces of revolution that has been part of Marxist-Humanism’s legacy since the 1950s. We note and support the leading role in challenging existing society played by the African-American masses when their mass movements question the basis of this society, as they did in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. We emphasize not only the power of the working class to bring down capitalism, but its creativity in developing new, human relations of production. We stand with workers against the union bureaucracies, politicians, and others who try to hem in their self-activity and integrate them into the existing order. We look for the return of the movement for women’s liberation born in the 1960s and 1970s, which spread around the world and deepened the concept of freedom by challenging sexism in nearly every aspect of every nation and culture. We look to the idealism of youth to help change the world. They have been in the forefront of the last half century’s social movements, particularly the movements against racism, nuclear war and imperialist wars, globalized capital, and environmental destruction.

We have come together as an organization because we believe that an organization is needed to fulfill our foremost aim, that of contributing to the transformation of this world by promoting, developing, and concretizing Marx’s and Marxist-Humanism’s bodies of ideas. This aim cannot be fulfilled by individuals working separately.

The organization created and headed by Dunayevskaya was capable of developing and concretizing Marxist-Humanism during her lifetime, but no organization currently exists that can fulfill these tasks. We seek to renew Marxist-Humanism by rebuilding an organization that can do so. We recognize that our small group is not that organization, but we hope to be a bridge to such an organization. That is why we call ourselves Marxist-Humanist Initiative. We are distinguished from the other organizations calling themselves Marxist-Humanist in this: we have the goal of rebuilding an organization capable of renewing Marxist-Humanism by concretizing and developing it as a collectivity.

A primary task of an organization with this perspective must be to create a collectivity of people capable of meeting this challenge. In contrast to other organizations since Dunayevskaya’s time that have called themselves Marxist-Humanist, we make the creation of such a collectivity a top priority. Further, we try to end the division between mental and manual labor in our own organization to the extent possible, and to build a non-hierarchical yet effective and sustainable organization.

We encourage you to contact us if you have questions or you would like to join this effort. There is a lot to do.

NOTES

[1] Raya Dunayevskaya, Marxism and Freedom: From 1776 Until Today, Fourth Edition, Pluto Press, 1975, p. 125 (quoting Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Charles H. Kerr & Co., p. 835).

[2] Marx’s humanism is evident in his Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844 and it continues through all of his work. Also cf. the transcript of a talk by Anne Jaclard and Andrew Kliman, “Marx’s Humanism,” July 31, 2013.

[3] Raya Dunayevskaya’s “trilogy of revolution” consists of Marxism and Freedom: From 1776 Until Today, Bookman Associates., 1958; Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre and from Marx to Mao, Dell Publishing Co., 1973; and Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation and Marx’s Philosophy of Revolution, Univ. of Illinois Press, 1991. Above are the dates and publishers of the first editions of these works. All are available in later editions.

[4] The full archive of Dunayevskaya’s works, The Raya Dunayevskaya Collection––some 17,000 pages in addition to her books, audios and videos––is housed in Wayne State University’s Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Walter P. Reuther Library in Detroit, MI. A digitized version is available at https://rayadunayevskaya.org/ . Included therein is her correspondence with Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, and Hegelian scholars such as George Armstrong Kelly and Louis Dupre.

[5] For an overview of Dunayevskaya and Marxist-Humanism, see the film available here. To hear Anne Jaclard’s personal remembrances of Dunayevskaya, listen to Radio Free Humanity, Episode 16: Dunayevskaya’s Life and & Legacy––Interview with Anne Jaclard.

[6] C. L. R. James’ followers are sometimes characterized as “spontaneists” because they believed that the spontaneous actions of the masses are sufficient to achieve a new (post-capitalist) society, while Dunayevskaya believed that spontaneous actions from below are necessary but not sufficient in themselves to achieve human freedom. She saw the need for a philosophy of liberation that is developed along with mass movements.

[7] Marxist-Humanist Initiative, “Why a New Organization,” April 10, 2009.

[8] “News and Letters Committees, Draft Resolution on the Book Marxism and Freedom: Method, Heritage, and Principles” (1956), p. 1.

[9] Talk by Raya Dunaveyskaya, “Dialectics of Revolution: American Roots and Marx’s World Humanist Concepts,” 1985, quoted in The Power of Negativity: Selected Writings on the Dialectic in Hegel and Marx, Lexington Books, 2002, p. 302.

[10] Raya Dunayevskaya, “Letters on Hegel’s Absolutes, May 12 and 20, 1953.” They were first published by Dunayevskaya in 1955, with an introductory note from “W” and a response from “H.” (The initials are short for “Weaver” and “Hauser,” pseudonyms used by Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee [Boggs], respectively. Lee was a co-leader, along with “Forest” [Dunayevskaya] and “Johnson” [C. L. R. James], of the Committees of Correspondence.)

[11] Cf. Andrew Kliman, “On New Passions and New Forces: Marxist-Humanism’s Break From Both Spontaneism and Vanguardism,” July 2, 2009.

[12] In the second edition of Marxism and Freedom, Dunayevskaya added two chapters––XXVII and XXVIII––on the thought and practice of Mao Tse-Tung.

[13] In one way, Marxism and Freedom can be viewed as an analysis of movements from practice, while Dunayevskaya’s second book, Philosophy and Revolution: From Hegel to Sartre and from Marx to Mao, has been called an analysis of movements from theory. However, that is a one-sided view of both books. Together and separately, they are grounded in Hegel’s dialectical philosophy of the process of self-development and realization––a unity of movement from theory and movement from practice.

[14] Dunayevskaya sought to build an organization that would engage in this process. An example of a different sort of organization, but one that also developed and projected theory and analysis in assistance to the workers’ movement, was KOR (Workers’ Defense Committee). It assisted Solidarnosc in Poland in the 1970s. See Mark Osborn, Solidarnosc: The Workers’ Movement and the Rebirth of Poland in the 1980s, Workers’ Liberty, 2020. It is also important to note that two intellectuals, Jacek Kuron and Karol Modzelewski, who were lecturers at the University of Warsaw and were involved with KOR, wrote “An Open Letter to the (Communist) Party.” It details their critique and analysis of the Polish economy and the “Communist” Party ruling class in the 1960s.

[15] “News and Letters Committees, Draft Resolution on the Book Marxism and Freedom: Method, Heritage, and Principles” (1956), op. cit., p. 4.

I had not quite so explicitly grasped that the American roots of Marxism was in the abolitionist movement, which Marx of course supported in his writings and organisational work. The contrast of abolitionism with the later formation of a general workers union in Baltimore, is a nice contrast to bring out Marx’s concern with much more than just the labour/class dimension in creating a society of free human beings.