by Eric Andrian

The UK government is hurtling toward crisis over the inability of Parliament and the Prime Minister to come up with a majority-backed plan for exiting the European Union.

While the Parliament continued to debate interminably over the terms for how the UK should leave the European Union (EU), on 23 March an estimated one million people (according to organisers, People’s vote) marched through the streets of Central London under the banner, “Put it to the People!” They demanded that the British people be consulted about the Brexit process in order to help break the government’s deadlock. The opposition Labour Party as well as parts of Prime Minister Theresa May’s own majority Conservative Party have defeated her EU backed plan for implementing Brexit three times.

This march—possibly second in size only to a demonstration against the Iraq war in 2003, and the second large march in six months on this issue—comes amidst the huge petition to Parliament for the revocation of Article 50 (on withdrawing from the EU) that had already garnered an unprecedented six million signatures.

The March for a People’s Vote

Green Party Member of Parliament (MP) Caroline Lucas was quoted as saying the march was “too big for anyone to ignore” and that

MPs returning to Westminster for crucial votes on Brexit this week should hear the echo of a million voices demanding that any final deal is put to the people. Indeed, the scale and passion of this People’s Vote march shows there is a vast well of support in Britain for a positive pro-European case.

The build-up to the event claimed: “Campaigners against Theresa May’s “my deal or no deal” Brexit strategy are planning to mobilise the public and politicians for a showdown over the UK’s future in Europe in the final six days before Britain is due to leave the EU…”

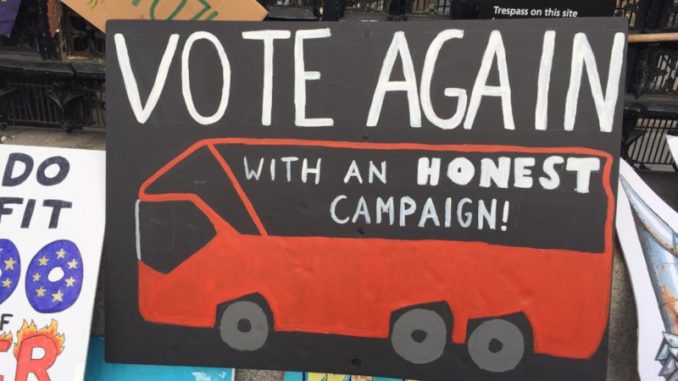

There were lots of slogans around the theme of “Revoke” (article 50) and “Remain,” and homemade placards expressed that many people who marched felt angry and fed up by the political indecisiveness of Parliament or the drawn- out manoeuvrings of Prime Minister May.

One fact-checking website estimated that around 400,000 took part, not a million, as others reported. The march was attended, as expected, by an alliance of many across the political spectrum (matching the divisions in population at large), including “soft” Brexit Labour supporters and pro-Remain Conservatives.

Source: Public Domain

Many observers and many who attended could be forgiven if they were under the impression that the demands of the march for a “People’s Vote” or “Second Referendum” was to cancel Brexit, and solely to support the “Remain” position of the whole debate.

The cross-party calls for Brexit supporters to join in the march exposed a radical-sounding populism that stresses the “reasoned” people versus an “indecisive” Prime Minister and Parliament. But this is actually an example of getting people behind the official opposition strategy of implementing the 2016 Referendum result to leave the EU, rather than the opposite. Indeed, the official Government response, rejecting the Petition demanding to stay in the EU, contains the gem:

British people cast their votes once again in the 2017 General Election where over 80% of those who voted, voted for parties, including the Opposition [my emphasis], who committed in their manifestos to upholding the result of the referendum.

Even within the Labour Party, many of the Remain supporters do not seem to realise that Leave is Labour’s official position. Not unexpectedly, much of the official Labour leadership and party machinery (including the campaigning group “Momentum” and the main trades unions) were either not officially represented or were noticeably absent on the day of the march, as Labour continues its electoral strategy of being all things to all people until it can snatch power from the Conservatives.

Source: Public Domain

How Did the UK Get Into Such a Mess?

With less than a week to go, PM May was in a quandary: how to get a hopelessly divided Conservative Party and Parliament to accept her Draft Withdrawal Agreement (“Plan B”) to leave the European Union (EU) on the revised deadline of 12 April?

Outside of the UK, people would have heard much about the “Brexit Crisis” and Britain’s “lack of readiness” with lurid headlines about, for example:

- Forecasts of a slowing down of the UK economy, despite record employment and businesses relocating abroad to EU countries, fleeing the UK because of uncertainty over customs tariffs and trade agreements;

- Predictions of traffic chaos at main UK ports such as Dover, due to the reestablishment of a UK/France border and customs checks;

- Government contingency plans—known as Operation Yellowhammer—involving 3,500 troops from the armed forces to “support government planning”;

- Warehouses running out of space as emergency stocks of food are piled up and warnings that Local Government should set up specialist teams to ensure the supply, distribution and safety of food; some people have even begun stockpiling goods in a British version of the American “preppers” movement;

- Worries over medicine shortages; UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock publicly refused to rule out that people could die due to medicine shortages if Britain crashes out of the EU in a “no deal” scenario.

- Worries over the growth of the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, extreme nationalist pro-Brexit realignment between the rump of the UK Independence Party and a far right coalition led by Steven Yaxley-Lennon (aka “Tommy Robinson”).

Brexit commentary here in the UK is noticeable for its frenzied speculation; every television, radio and social media news outlet has been pontificating daily on the almost mystical question, “Why can’t Britain just Leave already?”

If anything, many people have become quite weary of the information overload and inability of the politicians to resolve the deadlock.

Brexit is Not Quite a Done Deal

Within the last few months, PM May has faced repeated heavy defeats in Parliament of her Draft Revised Plan that she had spent two years negotiating with the European Union. The refusal of the House of Commons Speaker to allow a third rerun of the vote on a technicality and the catch-22 of the EU agreeing to an extension of the original 29 March deadline to the month of May if the Commons voted in favour of the Deal added to the air of deadlock in the political process; meanwhile plots abound to oust the PM as Leader from her own Party. A third Parliamentary vote on the Deal was recently defeated once again.

Touted as a done deal at the beginning of the year, May has spent the last two months with Plan in hand, trying to renegotiate aspects of it with an intransigent EU. She has shuttled around Europe twice in the process, met with the Leader of the Irish Republic (for which the main sticking point is the so called Northern Irish “backstop”) and held closeted discussions with leaders of UK opposition political parties and members of her own Party, trying to amass a promise for the requisite number of votes to allow the whole process to go ahead.

On 15 January, for example, May lost a vote concerning her modified Chequer’s Plan to leave the European Union—called the “Draft Withdrawal Agreement” (or “Plan B”)—by an unprecedented 432 votes to 202. She was defeated by a combination of rebel members of her own Conservative Party (especially the so called “Hard Brexiteers”, who want to Leave the EU as fast as possible without an agreement, i.e., the “No Deal” scenario), and mainly Remain (in the EU)/Soft Brexiteers supporting the Labour Party (LP) and other opposition parties. The following day, she narrowly survived a “vote of no confidence”, with the begrudging backing of a large section of her Party who were worried about losing power in an early General Election.

A big problem is that Parliament revealed in its voting (and also just recently in the late March series of indicative votes) that it disagrees with PM May’s Plan, but no one else has formulated any real alternative that could carry the majority. In this, the politicians are simply a reflection of the confusion and disagreements plaguing the country over how and whether Britain should “Leave” by other potential “Soft” or “Hard” options besides her Plan, or simply keep to the “Remain” status quo, and who should even decide: Parliament or another public Second Referendum vote (not to mention what should even be the ballot options!). Recent polls still highlight the sharp Leave/Remain split dividing the country, with barely any changes over time.

Source: Public Domain

The choices facing Parliament are becoming actually much simpler:

- Accept May’s “Plan B”, which is a “Soft” Brexit transition period involving leaving the political institutions of the EU but remaining tied to it economically in a Customs Union subject to EU trade laws, and with the ability to restrict immigration before leaving fully. There is strong resistance by UK politicians to Northern Ireland remaining under separate economic status with the EU compared to the rest of UK (the so called “backstop”) when this occurs.

- Reject “Plan B” and Leave with “No Deal”, forcing instant tariffs with the collapse of many free trade and cooperative agreements with the EU. (Parliament voted recently in an indicative vote to take this option off the negotiating table, although it could still happen by default if they do not agree on an alternative by the deadline.)

- Go for a delay by extending Article 50 beyond 29 March by a period of time to be negotiated with the EU (who are lukewarm about this, saying UK has had plenty of time to make its mind up); it was extended to 12 April and the EU offered a “flextension” (flexible extension) for up to a year.

- Go up to the deadline, hoping the EU will make more concessions to the Plan (which they have said they will not, especially over the “backstop” which affects the border between Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic).

- Rerun the Referendum with either May’s deal or “no deal” as the only options (her government has repeatedly said it will not go against the original democratic vote to “Leave”, so the “Remain” option is not on the cards at the moment).As of this week, it is PM May who still holds the only cards on the table in the form of an acceptable (to the EU) negotiated agreement, while Parliament dithers about whether to accept it. The clock is still ticking for our rulers to make up their minds.

What’s Wrong with a Second Referendum?

There has been a lot written in UK media claiming that a “Second Referendum” is somehow undemocratic, with the implication that it is an attempt by pro-EU supporters to undermine a democratic vote featuring one of the highest-ever voter participation. As it has turned out, even our rulers are confused over the meaning and direction of the original 2016 Referendum, which asked only: “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”

There is nothing wrong in principle with a new referendum in which people are allowed to change their minds on issues that affect them, provided:- The choices are clear and people are fully informed of the issues; the lack of clarity and fact-checking of the original options and subsequent claims on all sides led to much over-speculation in the media; the process even became worryingly susceptible to unprecedented voter manipulation via social media platforms.

- Maximum numbers of people are allowed to exercise their right to vote—prisoners, young people under 18, the three million UK-based EU workers affected, and even some British people abroad were not allowed to vote in the 2016 Referendum.

What is undemocratic is the silencing of the wishes of voters—now fully aware of all the facts and consequences of their voting—who may want to revisit their decisions.

The idea that somehow decisions are fixed for all time is a narrow vision of the democratic process, which sees people as only needed to tick boxes every few years, hoping that someone will carry out their wishes for them in an entirely passive process. The Referendum was unique in that it was the one issue which has roused the UK population out of its declining interest in the usual party politics for the first time in years.

If the mass of people will one day bring into being a new type of society, they will certainly need the democratic practice this situation provides.

Editor’s Note: On April 12, the EU granted the UK another extension to leave. This sets a new Brexit date of Oct. 31.

Be the first to comment