by Chris Gilligan

Abstract

The Irish border has been at the centre of debates on whether, and how, the UK can leave the EU. These discussions, however, focus on the issue of trade – the movement of commodities – not on the movement of people. This lack of attention to the realities of the lives of living, breathing, human beings fits with a broader, global, trend towards more authoritarian restrictions on human freedom. I also draw attention to the human dimensions of restrictions on immigration and immigrants in Ireland, North and South. I argue that immigration and immigrants are going to become even more restricted in the context of Brexit. I also note the possibilities for resistance to restrictions, and a grassroots movement for human freedom, in existing pro-immigration and pro-immigrant campaigns.

Introduction

The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is widely acknowledged to be the most difficult conundrum, in the negotiations over the United Kingdom (UK) leaving the European Union (EU). In the discussions about Brexit and the Irish border, there is a lot of talk about the movement of goods across the border. Both the UK government and the EU have expressed a desire to have a frictionless border for goods. But there is virtually no discussion about the movement of people. Opponents of a ‘hard’ Brexit argue that the UK should remain in the customs union, to avoid a hard border in Ireland. When they do so, however, their concerns are the impact that a hard Brexit would have on cross-border trade, the Northern Ireland economy and the fragile peace process. Those who, like Sinn Fein, argue in favour of Remaining in the EU, have had little or nothing to say about the treatment of immigrants.

The UK government, which is already struggling to develop a workable exit from the EU, seems to have side-lined the issue of immigration, in order to avoid further complicating matters. The official position appears to be, that the UK has a long-standing arrangement with the Republic of Ireland, regarding the free movement of citizens, between the UK and the Republic. This arrangement, the Common Travel Area (CTA), pre-dates both countries joining the EU, (both countries joined the European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor to the EU, on 1st January 1973). Both governments have affirmed their intention to continue to operate the CTA after the UK leaves the EU.

Some left Brexiteers appear to be reassured by the CTA. Peter Ramsay and Chris Bickerton, two left academics who helped found The Full Brexit, (a campaign for the UK to make ‘a clean break’ from the EU) , for example, have discussed the issue in a tone designed to reassure. “Free movement of people”, they have noted, “is guaranteed by the pre-EU Common Travel Area between Britain and Ireland”. This statement is misleading. The CTA is not a guarantee of free movement of people. It only covers some people, UK and Irish citizens. It does not cover the citizens of any of the other EU member states, or citizens of states outside the EU. The Republic of Ireland will remain in the EU. Consequently, EU citizens will retain the right to free movement, in and out of, the jurisdiction of the Irish state, but will not have an automatic right to cross the border into Northern Ireland. Several questions remain unanswered: will there be passport controls on the Irish border? If there are no passport controls at the border, what will happen in cases where, non-Irish, EU citizens cross the Irish border, (i.e. travel into Northern Ireland)? And what will happen if these non-Irish EU citizens then attempt to travel from Northern Ireland to elsewhere in the UK? Will there be, for example, passport controls for everyone who crosses the Irish Sea (by sky or by sea)?

These questions remain unanswered.

People who are sympathetic to immigrants might be relieved that, in the months since the referendum vote, the heat has been taken out of the immigration issue. Support for UKIP collapsed after the referendum, and the Conservative government’s ‘hostile environment’ policy was widely condemned in the wake of the ‘Windrush scandal’. The UK government has given a commitment to granting ‘settled status’ to EU citizens currently living in the UK, with a default assumption that applications would be automatically granted. Some also take comfort from the opinion polls, which show that hostility towards immigration has softened since the referendum. The issue of immigration may be out of the headlines, but that does not mean that the position of immigrants in the UK is any better. The issue of immigration has been depoliticised, not resolved.

Anyone who believes in a human-centred world, should be unhappy with the way that the topic of immigration has been side-lined, in the discussions about the Irish border. Immigration controls continue to have an impact on human lives. Every day, thousands of immigrants across the UK suffer the deprivation of their freedom, as they fester in the uncertainty of indefinite detention. We should not collude in the silencing of immigration as a human issue. Immigration is not something that can be captured in statistics. It is not something to be managed through policy tinkering. It is about real lives. It is about living, breathing, human beings. This article draws on statistics, and discusses policy. It does so, however, to give some sense of the extent to which immigration controls curtail human freedom in Northern Ireland.

The article is divided into six main sections. The first section provides some background, to explain why Northern Ireland has become a central focus for the Brexit process, and why there is much more at stake than most commentators recognise, or are willing to admit. Much of the discussion has focused on the issue of cross-border trade. Underlying this focus, however, has been the issue of sovereignty. The second section outlines these concerns and explains why the problem is not just one about territorial borders and national sovereignty. It is also about popular sovereignty; the question of who are ‘the people’ and what power do the people have to determine decision-making in society. The third section, draws together information from a range of sources to provide a detailed picture of the operation of immigration controls in Northern Ireland. The fourth section extends the discussion through looking at the likely future direction of immigration controls in Northern Ireland. The fifth section, switches the focus to the Republic of Ireland. Any UK exit from the EU will have consequences for the Republic of Ireland, yet there is even less discussion about this aspect of Brexit. This section looks at the Republic of Ireland as the frontline of what will become the EU’s most westerly land border. The closing section examines the issue of sovereignty, as articulated during the EU referendum, in the slogan ‘take back control’. In this section, I argue that accepting the scapegoating immigrants amounts to taking sides with employers and political leaders. For workers, taking sides against immigrants means giving control to employers and political masters, not taking control ourselves. Immigrants face many of the same challenges – low wages, insecure employment, uncertainty regarding their future, a sense that their lives are outside of their own control – that ordinary working people experience. I highlight a range of ways in which immigrants, and people working in solidarity with immigrants, are trying to take back control for themselves. I argue that ordinary working people have a common interest in standing in solidarity with immigrants, against employers and political leaders.

1. Why Northern Ireland?

Northern Ireland is one of the most intractable problems in the UK’s attempt to leave the EU. There are several reasons why this is the case. There is the practical, geographical, fact; that the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland will become the only land border between the UK and the EU. That fact makes Northern Ireland exceptional. If the UK leaves the customs union then there will be a need for checks on goods crossing the border. Checking goods will not be straightforward on a 300-mile-wide border, with over 200 crossing points. The issue is not just a technical one of how to check goods crossing the border. More importantly there is the issue of the terms under which trade will take place.

Some supporters of Brexit have pointed to the Sweden-Norway border as a model for post-Brexit Ireland. Sweden is a member of the EU, but Norway is not. Norway, however, is a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), which involves closely paralleling EU standards for the purposes of trade. This option is unlikely because most Brexiteers are lukewarm, or openly hostile, to joining the EEA. Doing so, they point out, would tie UK trade to the EU, without giving the UK any political say over EU trade policy. Others have suggested the Swiss model of border management as an alternative. Switzerland is not a member of the EU or the EEA. This example, however, is unlikely to suit the UK either. Switzerland, and all members of the EEA, allow for the free movement of EU citizens into their territory, for work. Ending free movement is one of the issues that the UK government says is core to Brexit. The UK government wants to more tightly regulate immigration and immigrants, EU free movement makes that very difficult.

The other difficult issue that threatens to derail Brexit, or to bring problems further down the line, is the tension between national sovereignty and popular sovereignty. At the heart of the 1998 Good Friday peace Agreement in Northern Ireland was an agreement to pool sovereignty. Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) Northern Ireland is partly governed from the UK and partly governed from the Republic of Ireland. Joint membership of the EU both enabled this sharing of sovereignty to happen, and disguised the fact of shared sovereignty. Brexit has revealed the range of ways, and extent to which, both parts of Ireland are integrated. It is not just trade that is integrated. There is also integration in healthcare, environmental policy, tourism, agriculture, education, the supply of electricity and citizenship.

The GFA achieved peace, of sorts, by taking the heat out of the conflict over national sovereignty. The signatories to the GFA did so, by fudging the issue of sovereignty. Leaving the EU involves the UK asserting national sovereignty. Brexit tends to cut through the fudge and bring the issue of sovereignty into sharper focus. It is the dilemmas of sovereignty, and all of the contradictions that sovereignty throws up, that make Northern Ireland one of the most intractable problems in the UK’s attempt to leave the EU.

The DUP tail wagging the UK dog?

Before going on to look at the issue of sovereignty, I want to briefly deal with the perception that the Northern Ireland issue is particularly difficult, because the Conservative government is being held hostage by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). In the June 2017 General Election, the Conservative Party lost their overall majority in the House of Commons. The Conservative Party entered into a deal with the ten Northern Irish DUP MPs, in order to maintain the Conservatives as the party of government. The DUP is vociferously opposed to any agreement with the EU, that would lead to a customs border operating across the Irish Sea, rather than on the land border with the Republic of Ireland. This stance, of the DUP, has seriously hindered the UK government’s room to manoeuvre, in its negotiations with the EU.

Critics of the DUP/Conservative deal point out that the DUP are happy to diverge from the rest of the UK on access to abortion and same sex marriage, both of which are illegal in Northern Ireland thanks to the DUP. Prime Minister Teresa May has been accused of facilitating Northern Irish backwardness, in order to maintain her government in power. The implication is that the ten DUP MPs are dictating policy in Downing Street.

UK government policy on Northern Ireland is not being driven by the DUP. Even if the Conservatives had an outright majority the Northern Ireland issue would still be the most intractable one. What the DUP are articulating is a concern that a customs border in the Irish Sea would mean that Northern Ireland’s position within the UK will be undermined. The DUP fear anything that they perceive would weaken the Union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The DUP are only articulating the logic of Brexit, which is to assert UK national sovereignty.

2. The Irish Question in British politics

The intractability of the Northern Ireland issue, is only the most recent manifestation of the long running issue, which has come to be referred to as the Irish Question in British politics. At the heart of the Irish Question is the issue of how to govern England’s oldest colony, Ireland. For centuries the Irish have resisted British rule in Ireland. The British ruling class have attempted to resolve the problem, of how to rule over people who resist that rule, through repression and through reform. But the issue has never been completely resolved. The British ruling class have tried various constitutional fixes. They have brought Ireland into the Union, (making it the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland), and, when that failed, they partitioned the island of Ireland, (leaving the north-east of the island, as part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland). After partition, they devolved power to a Unionist majority parliament (Stormont) in Northern Ireland. The local ruling class at Stormont governed through a sectarian ‘Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’. When that failed, the British ruling class imposed Direct Rule from Westminster. The GFA was greeted by many as an historic achievement. It sought to deal with conflicting aspirations for Irish and British national sovereignty through recognising both. It sought to prevent sectarian discrimination through establishing a power-sharing government and a range of measures to guarantee equality between Catholics and Protestants.

Ramsay and Bickerton are aware that the assertion of British sovereignty in Northern Ireland, historically, has involved imposing British rule through military might. As they put it, in an article in the Irish Times, “we tend to think of sovereignty (especially British sovereignty in the North) as a question of soldiers, prisons and union flags”. But, they go on to say, “sovereignty is really a question of taking ultimate responsibility for the fate of a territory and its people”. It is not clear what they mean by ‘really’. The implication appears to be that the imposition of power through military means is not ‘really’ sovereignty.

The conflict that broke out in Northern Ireland in the late 1960s, they imply, was because Britain failed to take responsibility for the fate of the territory and its people (“British governments have never shown much capacity to face up to it” [i.e. their sovereign responsibility to Northern Ireland]). After partition in 1921, they imply, the British government should have fully incorporated Northern Ireland into the rest of the UK, but instead “Westminster devolved responsibility to local sectarians and turned a blind eye to the discrimination and oppression that resulted”.

Ramsay and Bickerton are wrong to suggest that British governments have never shown much capacity to face up to their responsibility to Northern Ireland. The partition of Ireland and the devolving of power to local sectarians was the form in which they took responsibility. Partition did not appear in a fit of absentmindedness. It was part of a deliberate strategy to frustrate the struggle for Irish national self-determination. In the terms that Ramsay and Bickerton might put it, partition and Stormont were part of the assertion of Westminster’s parliamentary sovereignty aimed at undermining the assertion of Irish popular sovereignty.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty, that ended the Irish War of Independence, formalised the redrawing of the boundary of UK territory. The British ruling class relinquished direct control over the Irish Free State, (the original name of the state now known as the Republic of Ireland). Partition divided the struggle for national self-determination through splitting the movement into two different jurisdictions. The Treaty fomented divisions in the liberation movement in the Irish Free State. The forces of liberation divided over the terms of the Treaty, and the newly independent country descended into civil war.

The Treaty also confirmed the redrawing of the boundary of the sovereign people. In Northern Ireland Catholics were designated as a ‘disloyal minority’ and treated as second-class citizens. Successive Westminster governments were fully aware that Catholics in Northern Ireland were discriminated against and oppressed. That was the form through which British rule in the region was maintained. When Catholics in Northern Ireland asserted their popular sovereignty and resisted their oppression, initially through demanding civil rights, the local sectarians proved incapable of maintaining British rule in the region. At that point the British ruling class demonstrated their ultimate responsibility for Northern Ireland, by sending in British troops to reassert control. When that wasn’t enough to do the job, they simply set aside Stormont and imposed Direct Rule from Westminster. The British ruling class never gave up ultimate responsibility for the territory and people of Northern Ireland, what they did was subcontract it to local sectarians, and when those local sectarians proved incapable of securing control over the territory, they took back responsibility.

Shared sovereignty and the Good Friday Agreement

In the 1980s the British ruling class embarked on a new approach to Northern Ireland. It was Margaret Thatcher, (who is often perceived to have been a staunch defender of British national sovereignty), not John Major or Tony Blair, who negotiated and signed the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement. The 1985 Agreement sought to manage the threat to British rule in Northern Ireland through involving a foreign power, the Republic of Ireland, in the governing of Northern Ireland. This move to fudge the issue of national sovereignty pre-dated the 1987 Single European Act, (which brought about a single market within what was then the European Community), and the 1991 Maastricht Treaty, (which established the EU). This fudging of the issue of national sovereignty developed further with the peace process in the 1990s and was formalised in the GFA, which, in an exercise of popular sovereignty, was accepted by a majority of voters in both jurisdictions on the island of Ireland.

There are a number of ways in which the Good Friday Agreement (GFA), and the peace process more broadly, have attempted to fudge the issue of sovereignty. One of these has been to blur the territorial issue. The Irish border, as many commentators on Brexit have noted, has become almost invisible. Physical markers of territory have been erased. Border crossings which had been blocked were reopened. Border checkpoints, manned by the British Army, were removed. Military watchtowers, that used to command the high ground along the border, have been dismantled. On the political front, cross-border institutions, most prominently the North-South Ministerial Council, have been created.

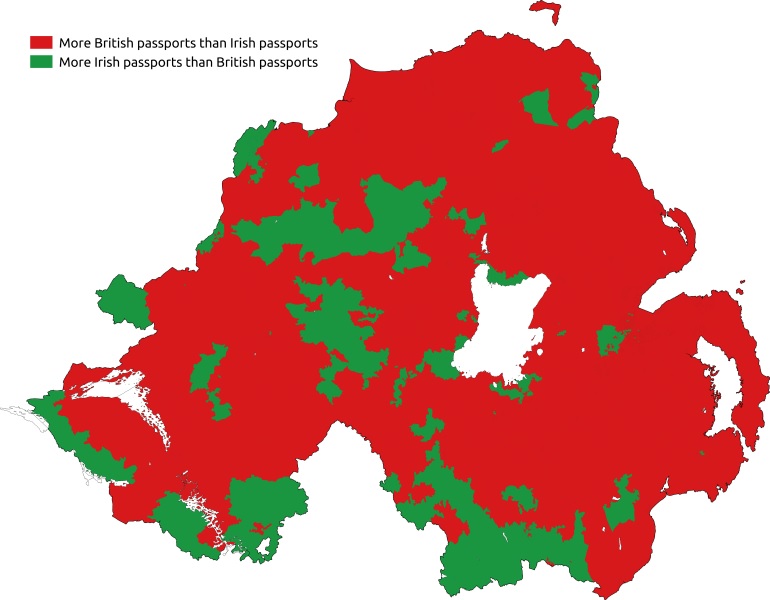

The Agreement also fudged the issue of “the people”, by allowing everyone born in Northern Ireland to have an automatic right to Irish or British citizenship, or both. This means that someone born in Northern Ireland can have Irish citizenship only, (i.e. not take up British citizenship), and enjoy exactly the same rights as someone who claims only British citizenship (Ramsay and Bickerton are misleading when they say that people in Northern Ireland ‘can opt for British and Irish citizenship’). The Agreement also guarantees that Northern Ireland can leave the Union and join the Republic of Ireland if a simple majority of voters choose to do so. This is a right which no other part of the UK enjoys.

Advocates of Brexit argue that the Leave vote should be honoured, because a majority of the electorate, on a relatively high turn-out, voted to Leave the EU. The case of Northern Ireland shows some of the limitations of this ‘it’s the democratic will of the people’ argument. Not only did a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland vote in favour of Remaining in the EU, a majority of the electorate also voted in favour of the GFA, with its in-built measures that blur the issue of sovereignty. The will of the people in Northern Ireland has been in favour of fudging the issue of sovereignty. The ‘democratic will of the people’ argument, claims that the majority vote in England and Wales overrides two majority votes in Northern Ireland, the Remain one and the GFA one. That is the logic of Ramsay and Bickerton’s argument. In Northern Ireland, Brexit is likely to bolster the perception that politicians at Westminster don’t care about this region of the UK.

Who are the people?

Ramsay and Bickerton also talk about ‘the people’ as if this category was self-evident. It is not. In the context of Northern Ireland do those who hold only Irish passports count as part of the category of ‘the British people’? In the event of the UK leaving the EU would these passport holders be required to prove their British citizenship, or acquire British citizenship if they were unable to do so? Ramsay and Bickerton might point out that the CTA, for all intents and purposes, treats Irish citizens as if they are British citizens. That means that all Irish citizens living in England, Scotland and Wales are British citizens.

Northern Ireland, and its people, have always been treated as an annex to, rather than integral to, the UK. This is true of politicians, academics and the British public. A recent poll by Lord Ashcroft, for example, found that only 28% of respondents in Great Britain, (i.e. the UK minus Northern Ireland), believe that Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK (8% said that it should no longer be part of the UK, and 57% that they either had no view, or thought that it was a matter for the people of Northern Ireland to decide). The same poll asked Leave voters in Great Britain what they would choose, if it was not possible to both leave the EU and keep England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales together in the United Kingdom. A majority (67%) expressed a preference for Leaving the EU, even if that meant the break-up of the Union. (Perhaps even more surprising, a much higher proportion of Conservative Party leave voters (73%), (a party whose full title is the Conservative and Unionist Party), than Labour Party leave voters (50%), would choose to leave the EU over maintaining the Union).

Who are ‘the people’ featured as an issue in various ways in the EU referendum. When the Westminster parliament was discussing the basis for the EU referendum there were arguments put forward that citizens of other EU member states, who were then living in the UK, should be allowed to vote in the referendum. The UK government decided, however, that they would not be allowed to vote. EU citizens were active in campaigning around the referendum. They did so, for example, through establishing groups like the 3million. This exercise of popular sovereignty, on the part of EU citizens, was excluded from participation in the formal exercise of popular sovereignty in the actual referendum vote. There were also, unsuccessful, calls for 16-17 year olds to be allowed to vote in the referendum. The point here is not about whether EU citizens or 16-17 year olds should, or should not, have been allowed to vote in the referendum. The point is that who count as ‘the people’ and what counts as an exercise in ‘popular sovereignty’ is not self-evident. These are things which are determined by people’s struggles, operating within existing structures. The form that the referendum vote took, or even the fact that a referendum was held at all, was decided in parliament, not on the streets.

3. Key elements of immigration control in Northern Ireland

Ramsay and Bickerton admit that ‘Brexit will require an external EU land border with cameras and electronic customs-clearing arrangements’. But cover over the human consequences of the border, and treat border controls as a normal and largely administrative matter, when they say that ‘the inconvenience of a border can be significantly lightened’ and ‘intelligence-led checks looking for drugs or illegal immigrants have been carried out in border areas during the past 20 years’. In doing so, they downplay the significance of the border for immigrants and people of colour. Immigration controls exist to facilitate the movement of some people, and restrict the freedom of others. It is not easy to get an accurate picture of the ways in which immigration controls in Northern Ireland restrict human freedom. But it is possible to piece together some kind of picture by drawing on data that is publicly available from various state, and semi-state, bodies. In this part of the article I draw together relevant data from these different sources, as a preliminary resource for active resistance to the inhumanity of immigration control.

Immigration control at ports and airports

Travel between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK is internal travel. In principle, taking a ferry across the Irish Sea, from Northern Ireland, to Scotland or England should be no different, from an immigration perspective, than driving across the Scottish/English or Welsh/English border. And taking a flight from one of the two Belfast airports, or City of Derry airport, to a destination elsewhere in the UK should be no different to taking a flight between any two UK airports. In practice, however, this is not the case. Immigration controls have been in operation at Belfast and Larne harbours, and at the airports, for decades. Over the course of the last two decades these controls have become more common. Home Office figures, obtained by the BBC, show that 468 people were ‘intercepted’ at border controls in 2014/15. These controls include those across the Irish Sea, as well as on the border with the Irish Republic. The BBC note that the figures for 2014/15 are a 71% increase on the previous year (274 ‘interceptions’). These ‘interceptions’ show that a border on the Irish Sea already exists.

Detention

Immigration detention differs from imprisonment. It is an administrative procedure, not a criminal justice one. Detainees have fewer rights than suspected criminals. Detainees do not get a trial. They do not even get to plead their case before a judge. It is the Home Office that makes the decision. In other words, immigrants can be deprived of their most basic freedom, without the state having to prove that there is good cause to rob them of their freedom. The state can do this, because immigrants are not citizens, and therefore they have limited legal protection against state coercion.

Limited protections for immigrants is not specific to the UK, it is also true of other EU countries. The UK, however, differs from other EU countries in operating a policy of indefinite detention. In other words, there is no maximum term for immigration detainees in the UK. In many EU countries the state is prohibited, by law, from detaining immigrants for more than twenty-eight days. In the UK approximately a third of all immigration detainees are held for more than twenty-eight days, and around a fifth for more than two months. One in a hundred are held for more than a year. The other ninety-nine out of a hundred don’t know if they will be held for a few days, a few weeks or a few years. All are at the mercy of the arbitrary power of the British state.

There is only one immigration detention facility in Northern Ireland, Larne House. The facility is located in the ferry port town of Larne and opened on the 11th of July 2011. It is officially designated as a short-term holding centre. It is deemed unsuitable for stays longer than seven days and unsuitable for children or families. Prior to the opening of Larne House immigrant detainees were held in police cells and in prison. There is no long-term detention facility in Northern Ireland. Consequently, immigrants who are lifted by the authorities in Northern Ireland are either deported within a week, moved to an immigration and removal centre elsewhere in the UK, to another ‘suitable’ location, or released. People can be released because it is established that they were wrongfully detained, or because their right to be in the UK has still to be determined and they are not considered to be a ‘flight risk’. In the latter case they are released on ‘bail’, ‘with a direction to report to Drumkeen Reporting Centre in Belfast as and when required’.

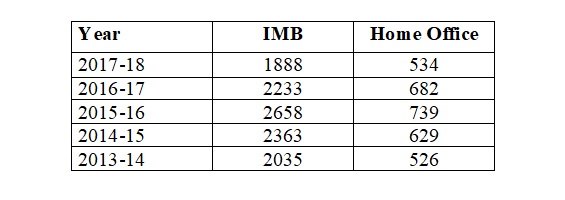

The publicly available figures on immigrant detention in Northern Ireland are difficult to interpret. The Home Office website records 629 people entered detention at the Immigration Detention centre at Larne in 2014-15. These figures, however, are dwarfed by the figures provided by The Independent Monitoring Board (IMB), the independent body that monitors all forms of detention in the UK (immigrant detention and prisons). The IMB reported that between the beginning of February 2014 and the end of January 2015 there were 2,263 ‘detainee movements’ in the Larne detention centre. The huge discrepancy between the IMB figures and the Home Office figures are baffling. [2] Whatever the explanation for this discrepancy, however, the reality is that hundreds of human beings are deprived of their freedom, every year, in Northern Ireland, without actually being charged with a crime.

Formally, immigration authorities operate with ‘a presumption in favour of release or alternatives to detention’ and only resort to detention if ‘there are strong reasons for detention’. If someone is detained, then the reasons why must be indicated to the individual concerned. In practice, immigration officials regularly flaunt the government’s own rules. The most recent report by the IMB, (on immigration holding and detention facilities at Glasgow, Edinburgh and Larne), for example, noted that, despite concerns being raised by the IMB every year, there was an increasing tendency for detention paperwork to fail to detail a reason for detention. The claim, that detention is only used when no alternatives are available, is also challenged by a 2017 Report by Amnesty International. This report pointed to evidence that detention has shifted from being used as a last resort, to being used routinely, in the UK.

Contrary to popular perception, most detainees in the UK enter the country legally. They do not arrive as stowaways. They have valid visas when they enter the UK as tourists, students, temporary workers, or when they come to visit family members already resident in the UK. They become irregular migrants when they fail to adhere to one of the stipulations in their visa. Most commonly this involves staying in the UK after their (holiday, study, work or visit) visa has expired. The main exception is asylum-seekers, some (but not all) of whom, arrive in the UK without the correct documentation and make a claim for asylum on their arrival. In the twenty-first century, policy regarding what immigrants are permitted to do, and what they are prohibited from doing, has become increasingly restrictive. One survey of policy has, for example, noted that between 1999 and 2016, ‘British immigration law has added 89 new types of immigration offences, compared with only 70 that were introduced between 1905 and 1998’. The same study noted the more recent trend, in the 2014 and 2016 immigration Acts, to force ‘third parties’ (e.g. landlords, doctors and employers) to act as border guards, by policing immigrants or people suspected of being immigrants.

It is for this reason that pro-migrant campaigners sometimes say that irregular immigrants are not criminals, they are criminalised. In other words, it is the maintaining of national borders, and the division of humanity by nationality, that criminalises the movement of human beings. Immigration controls are dehumanising, and detention is only one of the most obvious ways in which they are dehumanising.

Deportation

UK government statistics, on deportation and refused entry, do not provide a break-down that enables us to see the numbers for Northern Ireland. Since 2004, the UK wide figures have shown a trend, away from forced removal, to voluntary departure. This trend could be due to a less coercive approach on the part of government. Other evidence suggests a less charitable interpretation. The ‘hostile environment’ policy, the increasing use of detention in recent years, the brutal treatment of people in detention and the persistent complaints that immigrants’ access to justice is being undermined by government, suggest that the carrot of ‘assisted return’, may have become more appealing to many immigrants, because it is preferable to the threat of being beaten with the stick of brutal, and indefinite, detention.

Racial profiling

There is no official data on racial profiling in UK immigration enforcement. The Home Office denies that racial profiling plays a role in detecting immigrants who are guilty of immigration violations. Officially, UK immigration officers use an ‘intelligence-led risk-based approach to border control’. The intelligence part involves acquiring passenger, crew and freight information in advance of travel. This data is then supposed to be analysed based on known patterns of immigration rule violations, the risk-assessment part. This scientific sounding approach is administrative cover for racial profiling.

Evidence gathered from immigration operatives, by the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission, found that many immigration officials working at airports and ferry ports made decisions about who to take aside for more rigorous questioning, based ‘on “feeling”, “suspicion” and, in some cases, stereotyped views about certain nationalities’. In 2007, when the border agency was challenged about its practices, Elwyn Soutter, the agency’s chief inspector at the time, denied the charge of racial profiling. He explained to reporters, that his officers ‘question everyone, but inevitably EU citizens can quickly satisfy us. It is not terribly surprising to find it is people who are black or of other ethnicities who are detained’. In other words, racial profiling does not happen because immigration officers are racist, (although some of them no doubt are). Racial profiling happens because immigration controls are designed to enable ‘frictionless’ travel by relatively affluent Westerners, while also restricting the movement of the poor from the Global South. Put simply, immigration controls are racist by design.

The racial profiling involved in this ‘risk-based’ approach, has most commonly come into public view because of the harassment or detention of immigrants who have a right to be in the UK, but who are not believed by the immigration authorities. Soutter rationalised the border guards actions in the context of an out of court settlement with Frank Kakopa, a Zimbabwean national, who had been unlawfully detained by immigration officials after he arrived in Belfast City Airport, on a flight from Liverpool. Kakopa had been handcuffed in front of his wife and children, separated from them, detained, strip searched and then imprisoned in a cell with a convicted criminal. And all of this despite having identity papers and other documents that showed he had a right to be in the UK. Despite a number of cases being taken against the government, and compensation payouts in the millions being made each year for wrongful detention, the UK government continues to practice racial profiling in Northern Ireland, and the rest of the UK. A 2017 investigation, using data obtained from the Home Office via a Freedom of Information request, found that racial profiling was also operating in immigration checks on the street and in workplaces. This study found that almost one in five of those who were stopped, were British citizens.

Racial profiling is also in operation in the Republic of Ireland, and in cross-border immigration control operated by the principal immigration authority, the Garda National Immigration Bureau (GNIB). A 2012 exploratory study by the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI) found evidence of racial profiling by the GNIB. The researchers undertook two days of observation on the Dublin-Newry cross border bus route. They found that GNIB officers checked identity papers on cross border buses carrying visible minority ethnic passengers, but ‘identification was not checked on buses with no passengers from a visible minority ethnic background’. And one Black man was removed from the bus during the period of observation. They also undertook two days of observation on Dublin-Newry train journeys. They only witnessed GNIB officials board one of the trains during their observation, and these officials removed a couple, who appeared to be South Asian. No more systematic studies have been undertaken, and neither the GNIB nor the Irish government provide statistics that would allow for analysis of racial profiling in immigration stops.

Use of the PTA

The Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) was rushed through parliament by the Labour government in 1974. The Act was developed in response to Provisional IRA pub bombings in English cities. It was presented as a temporary, emergency, measure. It was renewed annually, using the justification that the threat from Irish Republicanism meant that the police and security services needed these powers to prosecute terrorism. In 2000, two years after the GFA was signed and passed into law, and a year before the September 11th terror attacks on the USA, the UK parliament voted to make the PTA a permanent Act.

Since 2000, critics have argued that the PTA gives extraordinary coercive powers to the state, including powers to silence protest. Critics have also argued that it does so without adequate mechanisms of democratic accountability.

The PTA is not formally concerned with immigration controls. Schedule 7 of the PTA deals with Port and Border controls. It gives the police, immigration officials and customs officers the power to stop, question and detain, anyone that they suspect ‘is or has been concerned in the commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism’. So, it is an anti-terrorism power, not an immigration power. The government’s own data, however, suggests that Schedule 7 powers are being used for immigration control purposes.

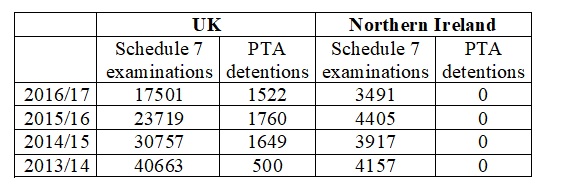

Schedule 7 powers obligates those who are stopped under these powers to answer questions, failure to answer questions is grounds for arrest. Schedule 7 also gives the authorities the power to take biometric data and remove and download the contents of mobile phones or other digital devices. The government appointed Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation has raised concerns, that racial profiling was being used to decide who to stop using these powers. Government data shows that, between 2012 and 2017, approximately a third of all of those stopped under Schedule 7 powers were either Asian or British Asian.

The Committee for the Administration of Justice (CAJ) have pointed out that Schedule 7 powers have been used more often in Northern Ireland than in the rest of the UK, relative to the number of passenger journeys involved. They have also noted that, despite the higher proportion of stops in Northern Ireland, there have been no PTA detentions of those stopped using Schedule 7 powers. None. Not one person, despite thousands of stops. This suggests that Schedule 7 is being used for something other than preventing terrorism. The CAJ suggested that the PTA’s ‘emergency type power may be being misused for routine immigration purposes’. My experience of passing through Northern Irish ports suggests that is certainly what is happening. On a number of occasions, at Belfast harbour boarding a boat bound for Scotland, I have witnessed the PSNI or border guards singling out people of colour for additional questioning. On one occasion, when I challenged their authority to do so, I was told that the person was being stopped under the Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Workplace raids and anti-trafficking

Not all people who are detained, or deported, are apprehended by immigration authorities at ports, airports or on cross border journeys. Some are apprehended at their place of work, some on the streets and some in their homes.

In addition, asylum-seekers who are not in detention are required to make regular reporting visits to immigration officials. These meetings are anxious events for asylum-seekers, because they know that these are occasions when immigration officials are known to take asylum-seekers into detention, with the aim of swift deportation.

Even a key piece of legislation that is commonly promoted as pro-migrant, The Human Trafficking and Exploitation Act (Northern Ireland), often operates as an extension of immigration control. Anti-trafficking policy in Northern Ireland is claimed to be victim and survivor focused. It is supposed to tackle forced labour and sexual exploitation. The official UK wide data suggest that, in practice, the policy acts more as an extension of immigration policy than it does as a means of tackling coercive working practices. In 2016, for example, 3804 people were scooped up under anti-trafficking provisions. A year later less than a third of these (1133) were considered to be legitimate victims of trafficking or forced labour exploitation, and a similar number (1168) were still awaiting a decision. A higher proportion had been judged to not be victims (1325). Campaigners have pointed out that many immigrants who are lifted as part of trafficking raids end up in detention, or being deported, or both. Critics also argue that the focus on trafficking takes attention away from the ways in which government employment and immigration policy creates the conditions for forced and precarious working conditions.

It is not clear the extent to which trafficking ‘victims’ in Northern Ireland end up being detained or deported. The first conviction for trafficking in Northern Ireland was in 2012, was a Hungarian man who was found guilty of trafficking two women into the UK, controlling prostitution and brothel keeping. The two women said that they were not being held against their will. In his sentencing the judge acknowledged this, but he said that he could not ignore that ‘human trafficking is a global problem and we should not be blind to the fact that it is happening right now in Northern Ireland’. In other words, despite the fact that the courts could not prove a case of forced migration and forced labour, the Hungarian brothel keeper should be made an example of, as a deterrent to human trafficking. It is not clear if the women were deported or detained, but after serving five months in prison the convicted trafficker was deported to Hungary.

4. Future trends in immigration control in Northern Ireland

This overview of immigration control in Northern Ireland indicates several things about current policy. Firstly, ad hoc passport controls are already in place at the land border and on the Irish Sea crossing. Secondly, that suspected irregular immigrants are detained at entry points in Northern Ireland. Thirdly, racial profiling happens at ferry ports as well as airports and on cross-border crossings by public transport. Fourthly, that immigration officials use non-immigration control powers, notably the PTA, to circumvent the legal constraints on them controlling free movement within the UK. Sixthly, that Northern Ireland immigration control involves cross border cooperation between the GNIB and UK based authorities, with some UK immigration policy being operated by ’remote control’ in the Republic of Ireland. Seven, that many aspects of immigration control policy and practice deviate from the stated policy, and commonly in a more restrictive direction. All these elements of immigration controls are likely to continue, if the UK leaves the EU.

There is a lot of uncertainty regarding the form that Brexit will take, and there is even the possibility that the UK will not actually leave the EU. It is clear that the UK state is not adequately prepared for even a ‘soft’ Brexit. The UK’s ports, for example, do not currently have the capacity to deal with customs controls on EU goods. And the UK is likely to continue to allow EU citizens to enter the UK on the same basis as currently, for the duration of the two year transition period, because the Border Agency and the airports currently lack the capacity for more rigorous immigration checks. Even with these caveats, however, it is clear that the general direction of travel is in a more restrictive direction, both at the border and for immigrants already in the UK.

Even if the UK remains in the single market, something that Teresa May has ruled out, immigration policy across the EU is likely to become more restrictive. It is notable that at the recent Salzburg Summit, where May’s ‘Chequers Plan’ was dismissed by EU leaders, the other main item on the agenda was immigration controls. The EU leaders were in agreement on the need to bolster FRONTEX, the EU’s border and coast guard, but continue to fail to agree on refugee burden-sharing between member states. The immigration issue is likely to continue to be a source of tension between the national interests of EU member states, and the supranational interests of the EU. The Summit also showed that it is easier for member states to agree on repressive measures, than it is on humanitarian ones. The hardening of borders is a trend across Europe, and much of the rest of the world. The rise of the xenophobic right, in government and as pressure groups exerting influence on government policy, is also another factor that indicates that, even if the UK remains in the single market, immigration control across the Irish border is likely to become increasingly restrictive.

Preparing for Brexit: securing the border (North and South)

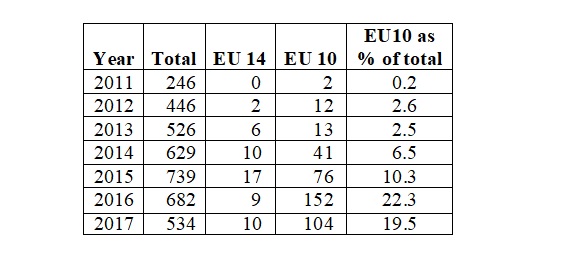

There is some concern that the UK government is already cracking down on EU immigrants, in preparation for leaving the EU. The UK government has given assurances that EU citizens living lawfully in the UK will be able to stay in the UK after departure from the EU. The government has introduced what they claim is a “short, simple and user friendly” process for EU citizens living in the UK to apply to remain. They have also said that their default position will be to accept rather than reject applications. The ‘living lawfully’ is a caveat which may see significant numbers of EU citizens denied the right to remain in the UK. It means, for example, that they have to have been living in the UK for the previous five years. The number of EU citizens deported from the UK has risen sharply in recent years. UK Home Office figures show that, for example, 50 Polish citizens were forcibly removed from the UK in 2007 and 1,160 were forcibly removed in 2017. The number of EU citizens in immigration detention has also risen in recent years. Both the trend in forcible removal and in detention of EU citizens can be seen in Northern Ireland too.

Alongside the talk of a seamless border there are preparations for enforcing the border. The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) has suspended the sale of three police barracks close to the border. Since the signing of the peace Agreement in 1998, there has been a process of demilitarisation in Northern Ireland. These three heavily armoured police stations near the border had been out of use and were due to be sold off. A PSNI spokesperson explained the suspension as ‘a precautionary step to ensure that, whatever Brexit looks like in the future, we will be able to continue to keep our communities safe’. The PSNI have also requested funds for more than 300 additional officers, for new vehicles and for other equipment, to help the PSNI support ‘other government agencies’.

The UK government has also been recruiting additional Border Force staff, in preparation for Brexit. This recruitment indicated some of the problems that a lack of understanding of Northern Ireland creates for UK policy. The advert for Border Force staff initially stated that the posts would only be open to British passport holders and that military service would be counted as relevant experience for applicants. Both requirements were reversed on the advice of the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland (ECNI), because both would disadvantage Catholics in Northern Ireland. Catholics are much more likely that Protestants to only hold an Irish passport, which they are permitted to do as British citizens born in Northern Ireland. Catholics in Northern Ireland are also significantly less likely than their Protestant counterparts to have served in the British Army.

The UK government has also attempted to bolster the, already draconian, anti-immigrant powers it has under anti-Terrorism legislation. The Counter Terrorism and Border Security Bill, introduced into parliament before the 2018 summer recess, proposed a mile-wide zone along the Irish border in which people could be stopped, searched and detained in order to check whether they are entering or leaving Northern Ireland. These powers are proposed as anti-terror measures, but, given the experience of the Schedule 7 powers, and the persistence of racial profiling at points of entry to Northern Ireland, it is very likely that they will be used to further police the movements of immigrants and people of colour.

South of the border the GNIB also appear to be gearing up for increased controls across the border. In early 2018 a member of the Irish Senate, who regularly crosses the Irish border on public transport, raised concerns that there was an increase in the frequency of passport checks by GNIB on the Belfast to Dublin route. Police in the Irish Republic have also requested the purchase of additional guns and increased firearms training, in anticipation of Brexit border controls. Because of the desire for ongoing cooperation on the Common Travel Area, the UK’s departure from the EU may also lead to a more restrictive immigration policy, for non-EEA nationals, in the Republic of Ireland.

These moves towards more policing of the border come against the backdrop of anti-immigrant bodies raising concerns about Ireland becoming a ‘back door’ to irregular immigration into the UK. Concerns about a ‘back door’ route are likely to increase as the Republic of Ireland increases its direct transport links to the EU, in response to Brexit.

Increased surveillance of immigrants in Northern Ireland

The attempts to introduce a mile-wide stop and search zone, on the Irish border, indicate that the repressive and restrictive nature of immigration policy is set to continue. In recent years, the UK government has been increasingly punitive in its approach to immigration. The hostile environment policy, introduced by Teresa May when she was the Home Secretary, was designed to make the UK such an inhospitable place for irregular migrants that they would leave of their own accord, or take up one of the government schemes designed to assist voluntary deportation. The Home Office has set removal targets which, like elsewhere in the target-driven public sector, has led to the ‘intricacies of people’s histories’ and personal circumstances being ‘reduced to statistics’. The surveillance and restriction of immigrants has increased dramatically over the last decade. The 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts, in particular, have turned teachers, NHS staff, landlords, bank tellers, letting agencies and university lecturers into border guards.

The Immigration Acts mandated that hundreds of thousands of people working in the public and private sector, who routinely come into contact with immigrants as part of their job, were expected to check the immigration status of the immigrants that they encountered. These aspects of the Immigration Acts have led to thousands of cases of discrimination, against both immigrants and people of colour who are British citizens. There are numerous documented cases of the racially discriminatory impact of the Acts. Take, for example, the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) investigation into the operation of the Home Office’s Right to Rent scheme. The JCWI found that the scheme, which requires landlords to vet their tenants, had ‘resulted in racial discrimination by landlords based on a tenant’s nationality and ethnicity’.

The 2014 and 2016 Immigration Acts have not yet been fully extended to Northern Ireland. The Right to Rent scheme, for example, has not been rolled out in this part of the UK. The government has, however, indicated its intention to extend the scheme to Northern Ireland. Any extension of the scheme can only mean increased surveillance of immigrants and a more hostile environment. Some observers have pointed out that the logic of the Right to Rent scheme, and other ‘everyday border guard’ elements of immigration law, leads to the need for UK and Irish citizens to carry ID cards. If immigrants are going to be charged for NHS treatment, or must prove their right to stay in the UK in order to be able to rent property, then the NHS and landlords will either, have to practice racial profiling, or they will have to require everyone to prove their UK citizenship. Others, including Mary McAleese, a former President of Ireland, have suggested that the logic of Brexit means there may be renewed attempts to introduce passport controls for movement within the CTA. Reassurances from Leo Varadkar, (the Irish Taoiseach/Prime Minister), that passport controls on the border were very unlikely, will not be very reassuring for immigrants in Northern Ireland. The UK government, he suggested, ‘would seek to control immigration not by physical checks on borders, but by imposing limits on rights to work and claim benefits’. Any such limits would likely lead to increased surveillance of immigrants, to ensure that they were not working, or claiming benefits, when they were not legally entitled to. People of colour, who are also UK citizens, are also likely to find themselves increasingly caught up in the web of measures designed to catch irregular immigrants.

5. Ireland and the border of the EU

So far, in this article, I have focused on immigration controls in Northern Ireland. I’ve only looked at the Republic of Ireland in as far as it is involved in helping to control immigration into Northern Ireland. When the UK leaves the EU, however, the Irish border will become the most westerly land border of the EU. Just as the UK will be keen to prevent the Irish border becoming a ‘back door’ into the UK, the EU will be keen for the border not to become a ‘back door’ into the EU. If the UK’s exit from the EU also involves leaving the customs union, then the Irish border may well become more like the one between Poland and the Ukraine, than the one between Sweden and Norway. The Polish-Ukrainian border is heavily militarised on both the EU and Ukrainian side and Poland and the Ukraine have only limited agreements on cross-border movement. The Irish government is also likely to have to more tightly monitor the movement of people from Great Britain to the Republic of Ireland, at Dublin, Cork and Rosslare harbours and at the country’s airports.

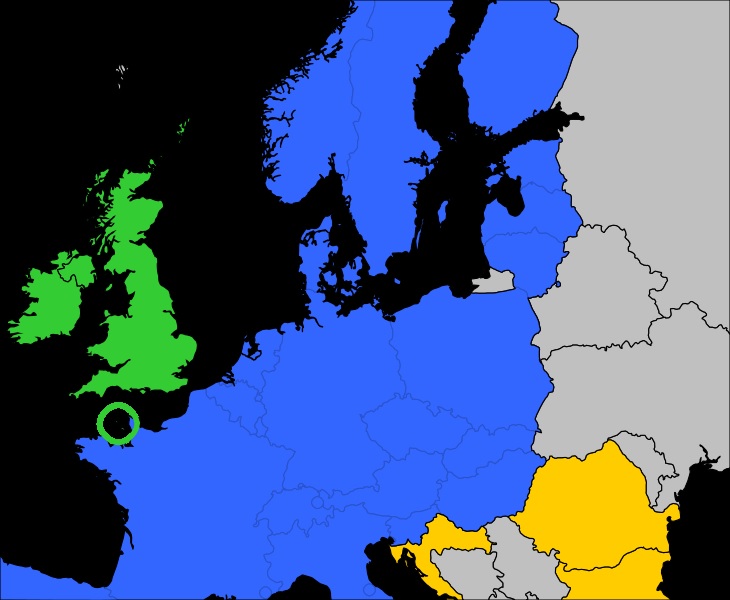

Increasing divergence between the UK and the Republic of Ireland may put strains on the CTA. Both the UK and the Republic of Ireland are outside of the EU’s version of the CTA, the Schengen Area. Schengen allows for visa and passport free travel between its member states. The members include 22 EU member states and four non-EU states (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland and Liechtenstein – all of which are relatively affluent European countries with extensive ties to the EU). If the UK exits from its free movement arrangement with the EU, but remains in the CTA, the Republic of Ireland will be in the anomalous position of being outside the EU’s visa and passport free arrangement, but inside a bi-lateral visa and passport free arrangement with a non-EU state. The contradictions involved in this anomalous position will put pressure on the Republic of Ireland to either act as an external frontier for UK border controls, or, what seems more likely, to rework the CTA and join Schengen.

To the casual observer the Republic of Ireland might appear to be a much more hospitable environment for immigrants than the UK. The Republic has undergone a remarkable shift from being a country of net emigration, over many, many decades, to becoming a country of net immigration, in a relatively short period of time. Unlike in the UK, this shift was not accompanied by the growth of anti-immigrant parties, like the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) or the British National Party (BNP). Nor does the Republic of Ireland operate a system of indefinite immigrant detention. The Republic does, however, treat asylum-seekers badly.

While asylum-seekers are not detained, their freedom is heavily restricted in other ways. Asylum-seekers have been prevented from working and, without any independent means, are dependent on the state for their housing, meals and subsistence. (This prohibition on working was overturned in July 2018, but it is too early to say what impact this ruling will have in practice). In effect, this system, known as Direct Provision, is a form of open prison. When it was set up in 1999, it was initially proposed as a system in which asylum-seekers would serve a maximum of six months, while their asylum claims were being processed. By 2018 there were approximately 5000 people in the system, many of them families with children. 2000 of these immigrants had been in Direct Provision for more than five years. Conditions in Direct Provision are so bad, that there have been hunger strikes in protest. In the decade 2007 to 2017 there were an estimated forty-four deaths in Direct Provision, and there have been reports of suicide attempts, self-harming and other indicators of poor mental health. Private providers are paid by the state to run the direct provision centres. These companies have profited handsomely from the misery of people caught up in the system.

The Irish government presents itself as a staunch defender of the GFA. What they fail to mention, is the fact that the Agreement has previously been re-interpreted by the Irish government, with the consent of the UK government, in a way that disadvantaged immigrants in Ireland. In 2004 the Irish government held a referendum, that was designed to exclude the Irish born children of immigrants from an automatic right to Irish citizenship. Pro-migrant campaigners complained that the proposed change to the Irish constitution would breach the Good Friday Agreement. The Agreement enshrined the right of anyone born on the island of Ireland to claim Irish citizenship. The Irish government gained agreement from the UK government that this right to Irish citizenship was conditional on “at least one parent who is an Irish citizen or is entitled to be an Irish citizen”. Several political parties in Ireland objected that this ethnic interpretation of citizenship was racist (see e.g. the Dáil debate on the Referendum). The change to citizenship was also opposed by two parties that were signatories to the Good Friday Agreement, the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Sinn Fein. Despite these objections, however, the Irish government held a referendum, which overturned the automatic right, of Irish-born children of immigrants, to Irish citizenship.

The UK’s exit from the EU is likely to lead to more surveillance and restrictions on immigrants in the Republic of Ireland. The historical record of successive governments in the Republic of Ireland indicates that they are much more likely to work with the UK government and the EU to restrict the position of immigrants, than they are to stand up for immigrant rights.

6. Taking back control?

One of the things that has become clear, from our survey of immigration controls, is the increasingly restrictive and punitive nature of immigration policy. In the UK, endorsement of restrictive and punitive immigration policy is not the preserve of Leave voters or Leave campaigners. Concern about immigration was a significant driver of the Leave vote. That does not mean, however, that people on the Remain side are pro-migrant. It was David Cameron, the Remain campaigning Prime Minister, who introduced the Conservative Party pledge to reduce net migration to the UK to the ‘tens of thousands’, back in 2010. Teresa May introduced the ‘hostile environment’ policy in 2013, while she was Home Secretary. Her department maintained the policy, while she was campaigning for the UK to Remain in the EU. Significant numbers of both Leave voters and Remain voters endorse restrictions on immigration and immigrants. In the wake of the Windrush scandal, for example, a Yougov poll found that 59% of Remain voters, and 84% of Leave voters supported the ‘hostile environment’ policy. Support for the UK leaving the EU is what differentiates Leave and Remain voters, not their attitudes towards immigration or immigrants. A majority of both Leave and Remain voters want the UK government to restrict the number of immigrants coming to the UK, and a majority of both support punitive measures against immigrants already in the UK.

The Leave campaign slogan which resonated most with voters was ‘take back control’. But why do ordinary working people lack control over our lives? It is not because the UK is a member of the EU. Taking power back from the EU, will not put it in the hands of ordinary people. It will put it into the hands of politicians and the British state.

Politicians against the people?

The idea that politicians don’t care about ordinary people, was a commonly expressed sentiment in the run up to the Referendum. The high proportion of Leave voters in regions of economic decline, like the North of England and South Wales, was interpreted by some on the left as a revolt against remote elites. It wasn’t a revolt. It wasn’t an attempt by ordinary working people to wrestle power from politicians, employers or the state. Since the referendum, working class Leave voters have been more likely to say ‘just get on with it’ (leaving the EU), than to say ‘we want power’. (In Northern Ireland there are echoes of this contradictory combination, of dissatisfaction with politicians wedded to demands for politicians to act. We can see it, for example, in the protests demanding the restoration of Stormont which coexist alongside cynicism about politicians and political parties).

If ordinary working people are to have control over our own lives, we need to take this control, collectively, for ourselves. One step in that direction, is to get to the roots of why we don’t have control. Brexit is a barrier to taking control, because it identifies the wrong problem. The two sides in the EU referendum campaign, only ever offered different versions of the same system.

Ordinary working people do not have control over our own lives, because it is politicians, employers and the state that control the levers of power. Many people recognise this. A recent study, by IPSO-MORI, for example, found that a majority of people in the UK (64%) ‘believe that the British economy is rigged in favour of the rich and powerful’. The Leave campaign channelled this sense of injustice and powerlessness towards scapegoating immigrants and the EU. The Remain campaign largely ignored the sense of injustice and powerlessness. Neither side of the Leave/Remain divide is trying to get to the roots of why capitalism produces inequality and imbalances of power.

Identifying immigrants as the source of problems in the UK, which many on both the Remain and Leave side do, identifies the wrong problem. The idea that immigrants are coming to the UK to steal jobs, or to take benefits, involves scapegoating immigrants. Immigrants are not, by and large, sneaking into the UK with the aid of people smugglers. They are being actively recruited by employers, and their agents overseas. UK universities are employing staff all around the world in drives to recruit international students. Agricultural producers are lobbying UK government to make it easier to recruit farm labourers from abroad. Rich and powerful employers are demanding that labour markets are rigged in their favour. Whether the UK remains in the EU or not, these demands for immigrant labour will continue.

Teresa May has recently reiterated David Cameron’s pledge to reduce net migration to the tens of thousands. That’s her headline advertisement for the Conservative Party. But before you buy it, read the small print. When May outlined her plans for the UK’s new immigration system, she told the BBC that her government would ‘be ensuring that we recognise the needs of our economy’. It’s the ‘needs of the economy’, not the needs of ordinary working people, that will dictate immigration policy.

Immigrants are not taking control from the hands of ordinary working people. But, when ordinary working people blame immigrants, and ask politicians to take action to restrict immigration, they are handing power over to politicians. Immigrants are being employed in agriculture and food-processing, as nurses and doctors in the NHS, as cleaners and warehouse operatives. They are being employed in these jobs because the ‘needs of the economy’ demand it. Employers are increasingly using zero-hours contracts, temp workers, low wage employment, and other forms of precarious labour, in order to satisfy the ‘needs of the economy’. As long as the millions of precarious workers in the UK blame migrant workers for their own plight, they are handing control over to their employers. Migrant workers are allies, not enemies, in the fight against precarious employment, and degraded working conditions.

It is not in the interests of ordinary working people to support, let alone demand, restrictions on immigrants. The hostile environment operates through surveillance and suspicion. It encourages us to act as snoopers and border guards. It encourages us to treat immigrants as enemies, not as potential allies.

Looking to politicians to place restrictions on immigration endorses the idea that politicians, or the state, can act as ‘saviours’ of ordinary working people. Lack of trust in politicians, when it is not also combined with attempts to take control into the hands of ordinary working people, feeds populist demands for strong leaders, who are willing to stand up to elites. Taking control, for ordinary working people, means taking power to ourselves, not alienating our powers to others to exercise for us.

Supporting restrictions on immigration is dehumanising. It involves treating living human beings as a category, ‘immigrant’, not as fellow workers or neighbours. It involves ignoring their humanity. It involves ignoring each person’s individuality. Supporting restrictions on immigration involves supporting a global form of apartheid. In involves propping up a global system that is rigged in favour of the rich and the powerful.

Supporting restrictions on immigration also leads to restrictions on ordinary working people. Restrictions on the liberties of immigrants are the thin end of the authoritarian wedge. It is always easiest to erode the freedoms of immigrants, because they don’t enjoy the same rights as citizens. The erosion of freedoms for immigrants, however, tends to erode the freedoms of citizens. This is obvious in the case of racial profiling, where citizens who are people of colour experience anti-immigrant surveillance. But restrictions tend to erode all of our freedoms. The increasing use of ID checks, which may lead to compulsory ID cards, is one example.

Resisting controls

Immigration policy is becoming increasingly restrictive, but many people are kicking back against the restrictions on immigrants. This is happening across the UK, Northern Ireland included. Civil liberties campaigners are drawing attention to ways in which the freedoms of immigrants are being eroded, and how these erosions are affecting, or are likely to affect citizens too. Migrant solidarity campaigns are working to challenge the dehumanisation of immigrants, and to erode the manufacture of us/them distinctions between citizens and immigrants. Precarity is something that afflicts increasing sections of the workforce, and migrant workers are particularly concentrated in precarious employment. Migrant workers, despite their relatively insecure resident status, are often leading the resistance to precarity. Independently of these struggles, Northern Irish citizens are challenging any attempt to re-impose a border across the island of Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission (NIHRC) and the Committee for the Administration of Justice (CAJ) are the two civil liberties organisations that have been most active around immigration related issues. The NIHRC, for example, has raised concerns regarding the Counter Terrorism and Border Security Bill. In a Briefing Paper on the Bill, they note that the proposed power to stop, search and detain, at ports of entry, and within the one mile zone around the border, can be invoked in response to a ‘hostile act’. They go on to point out that the term ‘hostile act’ has never previously been used in the UK outside of war-related legislation. They also note that the guidance on ‘hostile act’ defines it as ‘one that threatens national security or the economic well-being of the UK or is an act of serious crime’ (my emphasis). And they raise concerns that this guidance allows for broad interpretation by border guards and the PSNI. The CAJ has teamed up with academics at Queen’s University, Belfast, and Ulster University, to conduct research on the likely impacts of Brexit on Northern Ireland. The Reports that have come of this research raise a number of concerns, including; dangers to the peace process, the erosion of human rights protections, the likelihood of increased racial profiling, and evidence of a post-Brexit increase in racist intimidation (and an increased reluctance to report incidents).

Populists might sneer and say that these civil liberties groups are self-appointed ‘experts’ who like to lecture the ‘ignorant’ and ‘uneducated’ masses. There is some truth in this view, but that is not reason in itself to dismiss their warnings. Civil liberties groups play an important watchdog role in society. Experts in law are best placed to recognise and draw attention to attempts by government to restrict our legal freedoms. Often, critics of civil liberties groups are themselves self-appointed experts who are trying to defend particular interests in society. In Northern Ireland this has often been the case with Unionist politicians and lobbyists who have objected to human rights. The history of Northern Ireland should alert us to the fact that the most vocal opponents of civil liberties have often been political figures who wanted to maintain Protestant supremacy over Catholics. The history of Northern Ireland also shows, that civil rights demands were first advanced by middle-class legal ‘experts’. When, however, demands for freedom and equality were taken up by sections of the Catholic working-class, it shook the state to its very foundations.

There are now a number of, formal and informal, organisations that provide support and solidarity to immigrants in Northern Ireland. These include: the long-established Chinese Welfare Association, and the more recently established Romanian Roma Community Association of North Ireland; the refugee-led Northern Ireland Community of Refugees & Asylum Seekers, and the Christian inter-church based Embrace. They also include organisations like the South Tyrone Empowerment Project, UNISON (the public sector union) and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, that include pro-migrant activities alongside community and workplace based activity with non-migrants.

Migrant workers in Northern Ireland are actively resisting their precarity. This resistance is rarely documented. A 2010 research study collaboration, between migrant workers and researchers involved with the Independent Workers Union, provides some rare insights into migrant worker organisation in Northern Ireland. The authors of the report drew attention to the actions of some migrant workers who have successfully struggled against their employers, to secure proper contracts. In some workplaces, these actions helped to break down the divisions between ‘indigenous’ and ‘immigrant’ workers, and led to greater security for all workers, not just migrant workers. In other cases, the success of migrant workers did not manage to challenge the paternalistic, and often sectarianised, worker-management relations, that are characteristic of some workplaces in Northern Ireland. In these cases, employer ‘divide and rule’ practices co-existed alongside gains for migrant workers.

The creation of further border controls is also being resisted by Irish and British citizens. In October 2016 mock customs posts were erected, and traffic stopped, in protests organised by Border Communities Against Brexit, set up by people who live along the border. One survey of people living on the Irish border found that both Leave and Remain voters were anxious that the border remain as frictionless as possible. Another study, drawing on the views of people from across Northern Ireland, found that there was: ‘substantial and intense opposition’ to the possibility of border-checks; ‘substantial support for illegal or extreme protests’ against any North-South border checks, especially among Catholics and Sinn Féin voters, and; strong expectations that protests against border checks would quickly deteriorate into violence. This survey pointed to a major problem that the UK state faces in Northern Ireland, the fact that some sections of the population give only grudging consent to British state rule.

Finally, there are also pro-migrant campaigns and organisations, and anti-racist organisations, in the Republic of Ireland, that have an interest in working across the border, to resist increasing controls on immigration and immigrants. And pro-migrant and anti-racist organisations in Scotland, Wales and England that would benefit from remembering that the UK includes Northern Ireland, and from paying attention to what may become the frontline of anti-immigrant measures.

All of these factors, indicate that there is a clear possibility of disparate sections of society being drawn together, in opposition to border controls.

Conclusion

The discussions about Brexit and the Irish border have been dominated by the issue of trade. The impact of Brexit on immigrants is obscured in these discussions. Anyone who is interested in the struggle for human freedom should oppose this erasure of the lives of ordinary people. In this article I have drawn together data from different sources to highlight the restrictions on human freedom that are already being imposed on immigrants in Northern Ireland. I have also pointed to the evidence which suggests that, unless restrictions on freedom are more widely and vigorously resisted, Brexit is going to bring even more restrictions on the freedoms of both immigrants and UK and Irish citizens.

The discussions about trade and the border also obscure the issue of sovereignty. The question of sovereignty is worth drawing out into the open, because it highlights the issue of ‘taking back control’, and the limitations of using the concept of ‘sovereignty’ as part of any emancipatory movement to ‘take back control’ to ordinary working people, in all their diversity. Contemporary dissatisfaction with liberal democracy, highlighted by the Brexit vote and other manifestations of populism, signals a desire by ordinary working people to have more control over their lives. This stirring contains possibilities for freedom, but also dangers of authoritarianism. As long as sovereignty, rather than the independent self-development of the working-class and the oppressed, is the way in which ‘taking back control’ is conceived, the struggle for human freedom will be retarded. Conceiving of politics in terms of sovereignty helps to reinforce the nation-state, rather than challenging exploitation and oppression, as the framework for freedom struggles. It encourages ordinary working people to act as citizens and to alienate our own powers to our political masters, rather than encouraging us to act to gain self-mastery as a collective force for human emancipation.

Karl Marx once noted that: ‘Freedom is so much the essence of man [kind] that even its opponents realize it in that they fight its reality…. No man [or woman] fights freedom; he [or she] fights at most the freedom of others. Every kind of freedom has therefore always existed, only at one time as a special privilege, another time as a universal right’.[3] At present, in the various manoeuvres around Brexit, freedom as universal right is being attacked through demands for freedom as special privilege. Many ordinary working people in the UK believe that their freedom is threatened by the free movement of others. This belief has led them to demand that their political masters ‘take back control’ over immigration. This belief is a trap for ordinary working people. Instead of highlighting the different interests that separate workers from those who exploit us, it separates us from immigrants who are also being exploited and places us on the same side as our exploiters. Workers will not be able to take an independent stance, and fight for their own interests, as long as they take the same side as their political masters and exploiters. Both sides of the Brexit debate are encouraging ordinary working people to take sides with political masters – a pro-capitalist Leave or a pro-capitalist Remain – we should struggle against this and develop our own, independent, stance. One way to do this is to solidarise with immigrants in their struggles against oppression and exploitation. Another way is to challenge the division of humanity into different nation-states, by making connections across national borders. We can do this through linking up the anti-racist and free movement struggles in Ireland, Britain and beyond. One concrete way in which this can be done today, is to oppose any attempts to make the Irish border more restrictive.