by Ralph Keller

The effects of Brexit on the everyday lives of ordinary people are in plain sight, but they are not usually reported in the news media. Here, I’ll begin by overviewing where the United Kingdom’s relationship with the European Union stands, now that Boris Johnson has become Prime Minister. I will then draw on Marx’s Capital, and some facts that the media typically ignore, to work out what the effects of Brexit are likely to be, especially for ordinary people, and working people in particular.

The current financial situation around Brexit

Boris Johnson, or simply “Boris” as he is commonly referred to, became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (UK) on July 24, 2019. It is common practice, under UK parliamentary democracy, that the party with the most representatives in Parliament appoints the Prime Minister (PM). This also means that this party appoints a new PM if the current one steps down in between general elections; fresh elections are not necessary. Instead, a so-called “leadership contest” takes place within this party among candidates who “put their names in the hat”.

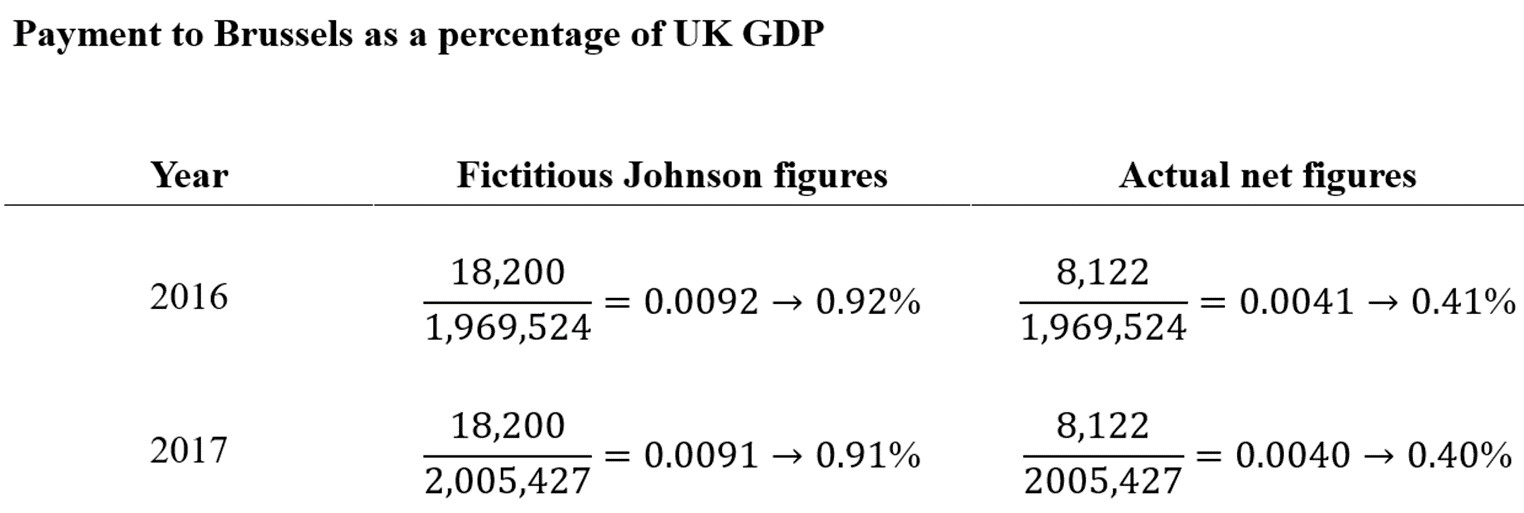

Johnson won the leadership contest despite being caught lying about Westminster’s financial contribution to Brussels. During his Leave campaign in the run-up to the 2016 Brexit referendum, he claimed that Britain pays a weekly sum of £350 million to the European Union (EU). The UK Statistics Authority recently clarified that the UK sends a sum of around £325 million per week (or £16.9bn annually), less the “UK rebate” negotiated in 1984 by then-PM Margaret Thatcher; the rebate amounted to £4.8 billion per annum in 2016-17. In addition, the UK receives money back from the EU for infrastructure projects, which means that the net payment to Brussels amounts to £156 million per week (or £8,122 billion per annum). The table below shows the annual figures as a percentage of GDP, which amounted to £1.970 trillion in 2016 and £2.005 trillion in 2017.

The table reveals how rich the UK is as a nation, and how little of this wealth goes to Brussels. To falsely report a higher portion of the UK’s wealth being “thrown out of the window”, Johnson generously rounded the £325 million per week up to £350 million, and neglected to factor in the Brit-Rebate as well as the money that the UK receives back from the EU. The table also shows that, even if Johnson’s fictitious claim had been true, the UK’s contribution to the EU would still have been less than 1% of the nation’s GDP. The UK’s defence budget alone, at 2% of GDP, is more than double the fictitious claim, and five times higher than the actual net payment. Leavers, however, would argue that the actual £8,122 billion per annum that is sent to the EU would be better spent at home––for example, on the National Health Service (NHS). Whether this will actually pan out to improve, or at least preserve, the level of health care that ordinary people receive remains to be seen.

For now, increased NHS spending, affecting the lives of millions, seems unlikely because the UK has bigger fish to fry in relation to Brexit. This is because the government would have to use tax money when the “divorce payment” to the EU of £39 billion is due. This is the amount that former PM David Cameron previously agreed to pay until 2021 as part of the EU’s 7-year financial planning. Moreover, the new government under Johnson has been busy preparing for a “no-deal Brexit”, committing an extra £2.1 billion for more border officers, stockpiling essential medicines, and a national program to help businesses. It seems unrealistic, in light of this situation, that the UK government will go on a spending spree to improve public services, as the Brexiteers touted during their Leave campaign. Shadow chancellor John McDonnell of the Labour Party described the extra committment as “an appalling waste of taxpayers’ cash”. There is nothing in Brexit so far from which ordinary people would benefit.

What is more, the prices of imported goods have already been rising. First and foremost, this is because the British pound started to lose value as soon as the Brexit drama was set into motion on referendum day, June 23, 2016. The bill for ordinary people is very likely to increase further, to cover the costs for border checks after Brexit, and, if no deal is reached, for trade tariffs under World Trade Organisation rules. The costs of these tariffs will be added to sales prices, if not in full then at least in part.

Johnson’s Brexit plan: not much new, but an unprecedented level of determination

Johnson’s Brexit “plan” revolves around the same main issues as did ex-PM Teresa May’s plan. Only the methods by which Johnson intends to go about these issues differ somewhat from his predecessor’s approach. The main points are the rights of the 3.2 million EU nationals in the UK, the Irish border backstop, the divorce payments, and the preparation for a no-deal departure.

Boris moving into No.10 Downing Street

The rights of EU nationals seem to be the most straightforward issue, since both the UK and the EU agree that EU nationals should be allowed to stay, provided that they lived in the country prior to a certain cut-off date. This provision is part of May’s Leave agreement with the EU. Johnson, however, has argued that it should be taken out of the Leave agreement and put into a separate law. This is new, and a distinct law would provide certainty for millions of people who would otherwise see their livelihoods endangered if Britain leaves the EU without a deal. But it is not an act of generosity. Instead, it is a reciprocal compromise, given that the EU intends to protect the rights of UK citizens living outside of the UK.

The Irish border backstop is part of the Withdrawal Agreement that Teresa May negotiated with the EU. It is a legal guarantee to maintain an open border between the EU and the UK along the Northern Irish border, in the event of the UK leaving the EU. If both sides cannot agree to a final deal at the end of a transition period that follows the UK’s exit from the EU, the backstop stipulates that there should be no new physical checks or infrastructure at the border.

Of all the issues connected with Brexit, the backstop is possibly the most fiercely debated. On the one hand, it has the effect of protecting the Good Friday Agreement of April 10, 1998, which ended decades of violence in Northern Ireland. On the other hand, even though the backstop will not apply if the UK leaves without a deal, Chancellor Sajid Javid, the UK’s finance minister, has nevertheless labelled the backstop “anti-democratic” because it seemingly ties the UK to the EU indefinitely. Hard-line Leavers like Javid believe that the UK would be substantially better off if it were allowed to forge its own trade deals, but the backstop prevents the UK from completely separating its ties to the EU. This situation allegedly prevents the UK from making better deals, because the UK would remain economically dependent on the EU.

However, this logic is made up out of thin air. This is because, Mr Javid, any trade agreement whatsoever will impose a sometimes uneasy co-dependence among the partners involved in the agreement. That is the reality of trade deals, plain and simple. Besides, the effort of forging fresh trade deals has not panned out well so far. Turkey, for example, has categorically stated that it will start negotiations with the UK only if, after leaving the EU, it nonetheless remains a member of the European customs union.

The difficulties involved in forging fresh deals to replace the current scale of trade with the EU have been among the reasons that many UK companies and business associations prefer a deal over no-deal. Johnson displays an unprecedented level of determination to leave the EU, however. To force Brexit through “with or without a deal” by October 31, 2019, and to be seen as a strongman in office, Johnson wielded the axe on Teresa May’s cabinet; on the day he became PM, he replaced most of her cabinet members with hard-line Brexiteers. He also sounded off on the backstop, touting: “Never mind the backstop, the buck stops here” (Metro newspaper, Thursday, July 25, 2019). He changed his tune somewhat shortly after, assuring Parliament that his preferred option is to leave the EU with a deal, rather than without one. This was a half-hearted attempt to back-peddle, after he received a hostile reception during his recent visits to Wales and Scotland.

The truth is, however, that signs are pointing toward a no-deal Brexit. Businesses and private households are now actively preparing for a no-deal departure from the EU, making use of the extra £2.1 billion in new Brexit funding that Johnson’s government has allocated.

To make Brexit happen at all costs, Johnson intends to use the £39 billion in divorce payments to the EU as a bargaining chip. But this is not a new idea either. Apart from the unclear legal situation as to whether the UK is allowed not to pay this money, withholding the £39 billion while a trade agreement is being reached was attempted previously, by David Davis, Brexit Secretary in 2017. But, in that case, Britain was the party that gave in, after only one morning of negotiations. Nevertheless, displaying a previously unseen level of determination, Johnson’s government is now combining the idea of withholding the £39 billion with the threat to leave the EU without a deal. The extra £2.1 billion that is being used to prepare for a no-deal Brexit suggests that this is not just an empty threat. Leaving without a deal is now becoming increasingly likely.

Jacob Rees-Mogg’s trade deals: inspiration for Sajid Javid

A no-deal departure is bad news for ordinary people. In addition to being faced with the Brexit divorce-payment bill, a no-deal Brexit would restrict free movement of labour, promote the further rise of nationalism and the Right, and would prompt worsening conditions in the workplace. A discussion of the facts alone cannot sufficiently illuminate these changes; bringing in the relevant theoretical context is in order at this point.

Bad news for ordinary people, and working people in particular

I do not intend to critique the EU as such. I will instead discuss why some firms in Britain, as well as about half of the public, favour leaving it.

One key issue is migration. To grapple with it, we need to understand why people migrate under capitalism. There are many reasons, of course, such as family or education. But the important question, when reflecting on the state of Brexit, is the underlying economic reason that workers migrate.

Marx, in Capital, volume 1, tells us much about how capitalism functions, in practice as well as in theory. One theoretical aspect that carries particular relevance in the context of Brexit is found in the chapter on the General Law of Capitalist Accumulation. This law pertains to machines displacing workers as production methods advance, e.g., through automation. According to Marx, this displacement leads to growing unemployment. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Eastern European countries have experienced, and still experience, this sort of capitalist accumulation. So where should the displaced workers in these countries go? Should they all live on income support in their home countries? Many of these workers are instead forced to leave, and to make a living in Western European countries, including the UK.

Once they are here, many find (low-paid) jobs, which in turn increases competition among workers in Western Europe. One way to respond to this is to “blame” the migrant workers, often by way of of racism and nationalism. Marxist-Humanist Initiative (MHI) has argued that these are pre-existing conditions, i.e., that they existed before the Brexit drama started to unfold. But the degree of racism and nationalism worsens as competition from migrant workers increases. This is because some workers in the host nation see migrant workers as a threat to working and living conditions.

The perceived threat is a consequence of capitalism’s defining economic law, the law of value, which

equalizes individual amounts of labour, expended to produce a commodity, to an average—the social amount. But the individual values remain in effect and thus aren’t equal. This is because different workers create different amounts of value per hour worked and thus get paid different amounts of money. Although there can be many other reasons why wages are unequal, the point is that there will always be wage inequality under capitalism—apart from these other reasons. Expressed differently, the other reasons only contribute to the degree of wage inequality; they do not create it. It becomes a “natural state”. Workers who are better off therefore reject the idea of possibly being worse off. And this leads them to embracing an idea that is “natural” under capitalism, the idea that their contributions are superior and thus deserve superior rewards.

Importantly, the law of value operates even in the absence of worker migration. But the existence of immigrant labour intensifies competition among workers. Immigrant labour is, therefore, often considered to be the actual source of worsening conditions among native-born workers, some of whom thus react by regarding themselves as superior to immigrants (an us that should not have to face job competition from them).

Unable to rein in or take control over the operation of the law of value, capitalist governments sometimes respond by closing the borders. So displaced workers are deprived of the possibility of finding employment abroad. The desire for the UK government to respond in this manner is a major reason that slightly more than half of the population voted Leave. (Such a response is impossible as long as the UK remains in the EU).

Another reason some people favour Leave is that they believe that this will allow the UK to regain full control over the nation’s laws. An article in MHI’s web journal, With Sober Senses, titled “On Brexit: The Sovereignty Trap,” dispels the myth that ordinary people will benefit from this move.

A third reason for favouring Leave boils down to competition, not among workers, but among capitalist enterprises themselves. In chapter 10 of Capital, volume 3, Marx discussed how the law of value plays out in the competition between more and less productive capitalist enterprises. It is reasonable to assume that many companies elsewhere in the EU are more productive than their UK competitors (though much investigation as to the extent of this phenomenon is needed). This implies, in terms of Marx’s labour theory of value (in chapter 12 of Capital, volume 1), that the less productive UK firms use more labour to produce a given amount of value (“social value”) than do their more efficient competitors elsewhere in the EU. Their labour costs are consequently higher.

One might imagine that they could compensate for this by charging higher prices. But one way in which the law of value exerts itself is by preventing enterprises from continually obtaining prices for their commodities that exceed the commodities’ actual (social) value. The way this plays out in practice is that enterprises that need to charge higher prices for their products find themselves unable to do so in the EU market, because they face competition from more productive firms in continental Europe whose labour costs, and therefore sales prices, are lower. If they were to try to charge higher prices, they would be driven out of business.

For these reasons, many UK firms have come to believe that leaving the EU, and then making their own trade deals, would allow them to compete more effectively—in those countries outside of the EU whose domestic enterprises are likewise less productive than those of continental Europe.

This belief goes hand-in-hand with the argument that unnecessarily complex EU “red tape” needlessly increases production costs, mainly because of the need to comply with overly-complex EU consumer legislation. There is more to this story, however. Instead of improving the efficiency and productivity of their production processes, many UK firms actively pursue a softening of working standards. This is, of course, bad news for working people. An article in MHI’s web journal, With Sober Senses, titled “Should the UK leave the European Union? Differing Ideas about the Coming Vote,” shows that, if Britain leaves the EU, UK workers would lose the protection from the European Directives that provide minimum standards for working conditions. Even if it leaves the EU with a trade deal in hand, these standards will no longer apply to workers in the UK. Concretely, this will mean that UK workers will have to sell their labour-power, i.e., their ability to work, during longer hours, while being exposed to lower social-security standards paired with stagnating pay. Lower pay and the previously discussed rising prices are doubly detrimental for ordinary working people.

Wrapping up

Although I have tried to dig deeper than the news media commonly do, I have barely scratched the surface in terms of the underlying reasons why one half of the UK favours Leave, and why that is bad news for ordinary working people.

This essay’s perspective on the motivations behind Brexit, and the likely consequences of the UK leaving the EU, did not start by opposing Brexit and then searching for arguments against it. Instead, it began with Marx’s theory, and with facts, and a perspective emerged as the discussion unfolded.

Although this perspective is definitely not pro-Leave, I also do not call for working people to align themselves with those British capitalists who favour Remain. While defending the freedoms already in place, such as free movement of labour within the EU, workers should, instead, aspire to rid themselves from the shackles of capitalism––that is, the law of value and the law of capitalist accumulation that were discussed above. This freedom cannot be realised by practical activity alone. Theoretical development is also needed.

Be the first to comment